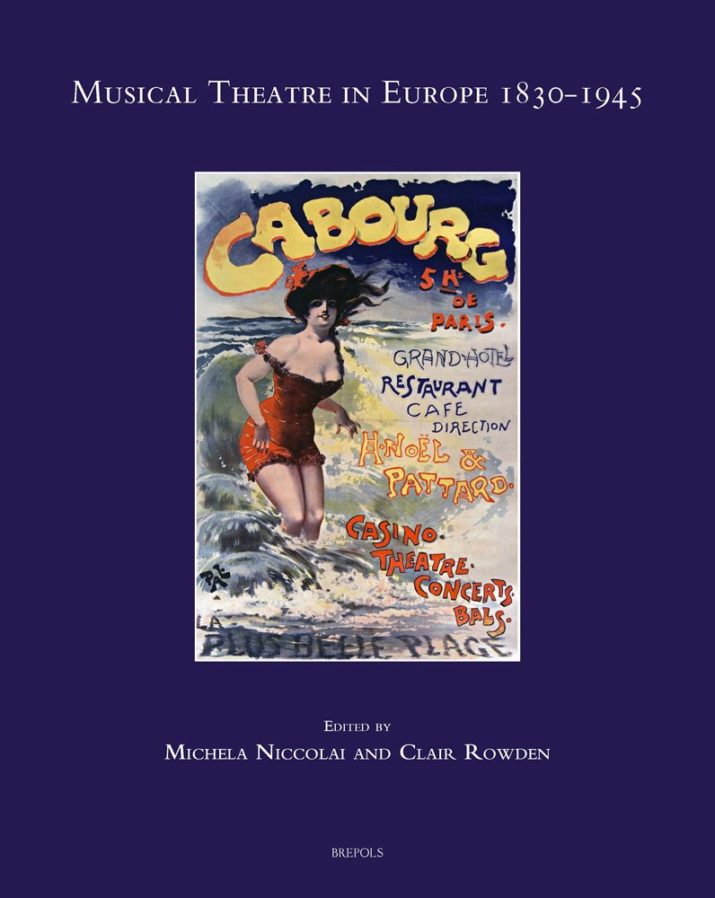

The lion’s share of scholarly literature that treats the subject of European musical theater during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries relegates itself to the study of “high” art, mainly in the form of opera. Musical Theater in Europe, 1830–1945, however, stands as a long-awaited corrective to this issue. Edited by Michela Niccolai and Clair Rowden, the nineteen multilingual essays that comprise the volume focus not on opera, but rather on music performed in social venues such as music-halls, cabarets, and café-concerts, paying particular attention to opera’s lighter cousin, operetta. Appearing in print for the first time in 1856, the term operetta generally—though not always, as Niccolai and Rowden aptly note in their introduction—parodied well-known operas, integrated opera’s three constituent elements (music, theater, and dance), and left the audience humming memorable melodies. A prime example of such a tune is the infernal galop from Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Orphée aux enfers (1858)—more popularly recognized as the can-can. As numerous essays in the collection point out, however, scholarship on operetta and similar parodic genres, such as the focus of Olivier Bara and Richard Sherr’s essays, the Revue de fin d’année, tend to situate these works on the fringes of European musical life, their ephemerality often contributing to their dismissal.

The lion’s share of scholarly literature that treats the subject of European musical theater during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries relegates itself to the study of “high” art, mainly in the form of opera. Musical Theater in Europe, 1830–1945, however, stands as a long-awaited corrective to this issue. Edited by Michela Niccolai and Clair Rowden, the nineteen multilingual essays that comprise the volume focus not on opera, but rather on music performed in social venues such as music-halls, cabarets, and café-concerts, paying particular attention to opera’s lighter cousin, operetta. Appearing in print for the first time in 1856, the term operetta generally—though not always, as Niccolai and Rowden aptly note in their introduction—parodied well-known operas, integrated opera’s three constituent elements (music, theater, and dance), and left the audience humming memorable melodies. A prime example of such a tune is the infernal galop from Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Orphée aux enfers (1858)—more popularly recognized as the can-can. As numerous essays in the collection point out, however, scholarship on operetta and similar parodic genres, such as the focus of Olivier Bara and Richard Sherr’s essays, the Revue de fin d’année, tend to situate these works on the fringes of European musical life, their ephemerality often contributing to their dismissal.

Positioning operetta as a “lowbrow” counterpart to “highbrow” opera, however, runs counter to one of the primary themes of Niccolai and Rowden’s volume. Indeed, one of the major contributions of this work is the dismantling of such binary constructions as high versus low art; the concept of crossover, whether between high and low art, parody and original, or even between the concepts of local and transnational permeates the work. Alessandro Maras’s contribution, “La revue de fin d’année, entre divertissement et avant-garde: le cas Apollinaire,” argues that the modernist art of the early twentieth century (cubism and surrealism) championed by Guillaume Apollinaire could not have existed without the popular art form of the end-of-year revue. In a similar move towards blurring boundaries, Catrina Flint de Médicis’s essay on the French poet Maurice Bouchor and the Petit-Théâtre de la Marionnette argues that the fraught reception of puppet plays demonstrates a crossover between highbrow puppet productions, intended primarily for the Parisian intelligentsia with Symbolist leanings and the more populist folk traditions of southern France. In “Street Cries on the Operatic Stage: Offenbach’s Mesdames de la Halle (1855),” Jacek Blaszkiewicz further challenges the notion that such “light” music is necessarily inconsequential. Tracing the seemingly unconnected lineages of urban street cries and operatic choruses, Blaszkiewicz deftly reveals the coexistence of an urban past, sonically represented by vendors’ street cries, state-sanctioned plans for urbanization, and Offenbach’s chorus to show how Mesdames de la Halle—regarded in the 1850s as a watershed in Parisian theatrical history—transgressed the divide between historical and modern in an otherwise “trivial” genre.

Other essays, particularly those by Stephanie Schroedter and Clair Rowden, engage with crossover in less overt ways. Schroedter, whose focus is dance in Offenbach’s operettas, does not limit her discussion to dance as a complimentary art form to music. Rather, she demonstrates the many crossovers between music and dance in order to argue that, in Offenbach’s works, music transgresses generic boundaries and becomes dance. For Schroedter, choreographed movement becomes an imagined “sonic” dance on the stage: to use her words, Offenbach’s characters “are not really dancing even when they are dancing. Instead they ‘are danced,’ that is they cannot help but submit themselves to a movement impulse which originates less in themselves but forces its way into them through the music” (102). It is precisely the genre of operetta that enacts this crossover: whereas the dance scenes of grand opera and opéra-comique were part and parcel of the dramaturgical context, the momentum of the operetta, as a parody of such established genres, feeds into and out of the parodic elements and embodies a dance that is catalyzed by nothing else than the music itself.

The volume also situates operetta as a transnational genre. Whereas previous studies have largely considered Paris to be the epicenter of operetta production and, in some cases, experimentation, a number of the essays in Niccolai and Rowden’s collection take other European locales as their starting point—a feature represented by the international diversity of the authors themselves and the multiple languages that are represented in the volume. But the authors do not limit their engagement with transnationalism to a mere relocation of operetta performance from Paris or Vienna to Spain or, in Naomi Matsumoto’s essay, Japan. Instead, they reveal the ways in which cultural engagements transform as they circulate internationally, affected by place and space as well as audience. Matsumoto’s study of the Italian director and dancer Giovanni Vittorio Rosi illustrates the transnational reconfiguration of European operetta into a hybrid form that, when taken by Rossi to Japan during a period of intense Westernization, detached itself from its European cultural contexts and was employed for new and different cultural, social, and political ends. The theme of transnational adaptation continues in Maria José Artiga’s essay “Deconstructing the National: The Operetta Maria da Fonte.” Her examination of Offenbach in Portugal tells the story of how the Generation of the 1870s—a group of intellectuals and writers who quickly became dissatisfied with the slow pace of Portugal’s democratization and economic development—repurposed a light-hearted and satirical musical genre into a vehicle for profound social and political criticism. For the Generation of the 1870s, Offenbach’s operettas were considered to be “philosophy in song” by virtue of their allegorical critique of Parisian bourgeois culture (457). One product of this intellectual movement was Maria da Fonte, an operetta that told the story of a young, tough, and anticlerical woman who was known for her bravery and humanity in the face of governmental injustices. As Artiga shows, however, the lack of parody, allegory, or metaphor—all key dramatico-musical elements of Offenbachian operetta—ultimately rendered the work unsuccessful; the writers’ reliance on realism in their work essentially undercut their transnational co-opting of Offenbach’s parodical satire.

Like Maria da Fonte, many of the works that appear in this volume have long since fallen out of the standard Western performance repertory—a fact that evinces the ever-present superiority given to canonical works in musicological scholarship. Yet Niccolai and Rowden’s volume makes significant headway in the effort to restore operetta, parodies, and other forms of popular musical entertainment to the position that it once held in European society. Many of the divides that this volume strives to narrow remain prominent in musical performance and study today, and in particular the notion of “high” art versus “lowbrow” entertainment. One of the numerous successes of Niccolai and Rowden’s volume is the seamless way in which it demonstrates how a supposedly “light” musical genre can itself bridge this gap. Clair Rowden’s essay posits parody as “criticism in action:” as “pluri-focal networks of texts, signs, songs, and meanings,” works like operettas and parodies gave their audiences both agency and delight (115; 133). Indeed, the volume itself is “criticism in action.” It invites its reader—specialist and non-specialist alike—to take part in the rich tapestry of signs, songs, and meanings that is European musical theater.

Reviewed by Jennifer Walker, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Musical Theater in Europe, 1830–1945

Edited by Michela Niccolai and Clair Rowden

Publisher: Brepols

Hardcover / 479 pages / 2017

ISBN: 978-2-503-57766-1

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on July, 2 2018.