This is part of our special feature on Anxiety Culture.

The Moving Matters Traveling Workshop (MMTW) is a transdisciplinary experiment. This mobile art and scholarship laboratory tests, enacts, and teases out the idea that subjects are formed not simply by sharing territory, blood or nationality, but according to the paths they have followed. Do commonalities arise due to similar experiences of migration? Or following similar daily paths within a neighborhood or across a city ? The artists and scholars who founded the MMTW have all had multiple experiences of migration: they are serial migrants. [1] They draw on this experience to produce art on mobility and migration that exposes and explores the choreographic powers that shape a world in motion even as dominant ideologies maintain discourses of territorial bias for politics and culture.

Moving to a new county is among the most dramatic changes one can experience. Whether someone is displaced by war or famine, exiled for political reasons, or decides to move for love or a job, migration is an anxious interval between homes. For some people, this liminal period stretches indefinitely to make being a refugee into an enduring identity. For others, it sets out the beat of immigrant life with its back and forth motions between adopted homes and places of origin. To settle is not just a matter of learning the ropes of a new culture or becoming accustomed to being a stranger—it entails developing strategies to find one’s balance in a lifeworld strung between there and there. People whose migratory journeys disturb their ability to engage this process and those who must find a way to live “between” without the possibility of return to their birthplace, learning to dance the two step of immigration, presents particular challenges. Those who have migrated under duress and lived through traumatic events, encounter uneven, mined landscapes everywhere. Exiles join the immigration dance with a phantom leg. Even for people with the “best” passports, higher education, and a modicum of wealth, migration and immigration inspire tremendous fear, doubt, and trepidation, as well as hope. Immigrants are themselves anxious objects for some “locals.” While they are occupied with keeping up with the oscillating space of their lives, many simultaneously confront the hostility of those who defend static, territorial politics and reified notions of culture and belonging.

Migration and its aftermaths are thus fraught with anxiety: the MMTW not only addresses these multiple anxieties in artwork, performances and exhibitions, but structures its action as a suite of anxious scenes of migration. The project was started by a small group of serial migrant artists and scholars in 2013. It develops by devising one site-specific event after another. In each site, we confront the angst of living in a new environment with the task of developing art on migration and mobility that is meaningful for changing locations and publics. To date, we have worked with museums and tourist sites, centers of contemporary art and theaters, working across artistic and academic disciplines to produce exhibitions, performances, and public interventions in France, the Netherlands, Romania, Germany and, the United States.[2] At each stop, we invite new artists and researchers to join us; at present, fifty-four visual artists, academics, composers, writers, and choreographers have participated. The size and composition of the group changes from meeting to meeting. Twenty-five individuals participated in the month-long events at the Berlin wall monument last June. Interventions at conferences or pubic plazas involve just two or three people. In each site, we work closely with institutional partners and sometimes with other groups of artists. For instance, in Los Angeles, the Son of Semele Ensemble developed a collaboratively written play inspired by our work and the Het Sannas and DoreMimi choirs just joined us for a performance in the portrait Gallery of the Hermitage Museum in Amsterdam in May.

This format and process has proven to be immensely productive. As Blanca Casas Brullet recently wrote to me, “each workshop brings up different, contrasting feelings for me; at once desire and anxiety; one never know which group dynamic will be set up. We know some of the people, but not all. Each workshop is a new distribution of the cards. Will we work well together? Will it be enriching? The situation is indeed like migration. You can’t control it. There are so many unknowns. You have to forget yourself a bit and adopt an experimental stance. Your need to get into the process and ‘forget’ the outcome and lay aside questions of profit or career. There are no guarantees, it is actually liberty that one gains.”

Alec Balasescu notes that the MMTW is “a structure that allows [him] to experiment and transform [his] anxieties into a form of expression that may be easier to perceive than the raw emotions themselves. Although, it is true, a few times things were very emotionally charged, especially in the periods of limbo when I didn’t know where I’d be living next.” His “deep anxiety regarding the rise of nationalism and populism, a rhetoric that has at its basis an anti-migration and anti-free movement politics of fear,” feeds into his work with the MMTW (see his story “Adopt a Canadian”). Kayde Anobile concurs, remarking that working with the MMTW has made her “more aware of the privileges she has enjoyed in her own migrations, and helped her to better understand the migratory experiences of others as well as herself.”

Over time, the MMTW has generated a consistent mobile social space that encourages the development of a unique repertoire and method of working across disciplines, media, and forms of presentation. A film of us devising a performance at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam in 2014 by Blanca offers a glimpse of the workshop in action. It illustrates Alec’s comment that with the MMTW he is often “simultaneously performer, organizer and curator, needing to re-for my role with any given situation.” Recent articles by Priya Srinivasan, Alec Balasescu and Olga Sezneva also offer windows in the life of the collective from the perspectives of a choreographer-critics and anthropologist-writers. Lisa Strehmann reflects on working with the MMTW as a collaborating community activist.

The productivity of the workshop is rendered visible in the development of single series of works by individual artists, as well as in the collective performances and exhibitions. The works selected for this on-line exhibition both take the anxieties of migration as their subject and show the effects of repeated enactment of the scene of migration in life, and in the art of the MMTW.

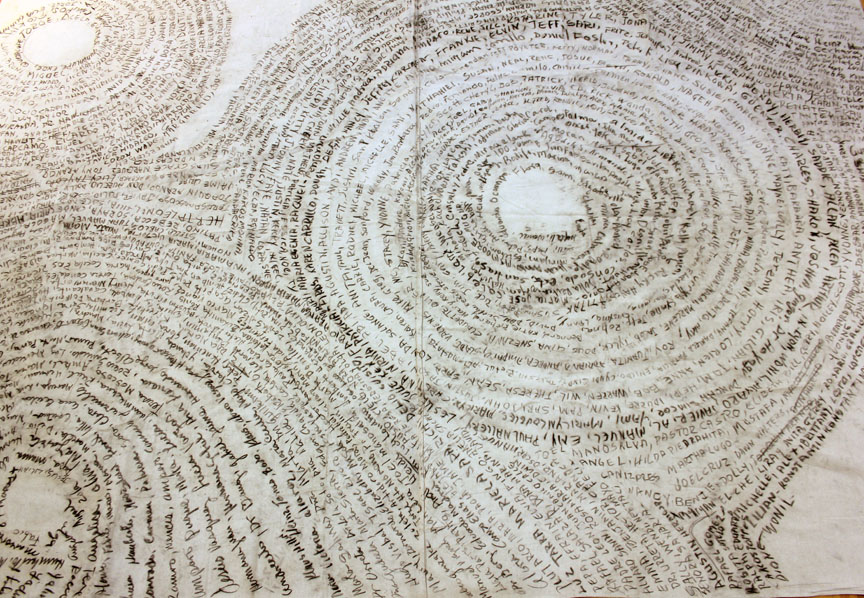

Beatriz Mejia-Krumbein conceived Mi Tiempo, Mein Raum, My Map for the very first meeting of the MMTW in May 2013. She told me how she sat on the canvas and tried to recall the names of everyone she had met in Columbia, Germany, Mexico, and the USA, her several home countries. As she remembered each person, she wrote their name in one or more of the spirals that represented a country (figure 1). Once completed, she used the canvas as a moving ground for a performance in which she recites the names as she moves amidst the spheres/homes in a mimetic reenactment of her migratory path. Beatriz explained that “the work responded to a kind of anxiety, the way you imagine pulling up your roots, and up developing a new world of your own by making new relationships across borders. It is a very difficult process. Anxiety and joy dance together as the path unfolds.”

The performance evolved as we moved from California to Clichy, France and Los Angeles, both as an individual piece, and in relation to the changing topics of the workshops (figures 2 and 3). Beatriz added additional elements and eliminated others. For instance, at the initial performance, she placed white blocks on each country/spiral in 2013, as though for emphasis. She hung quilts over them which she removed when she mentioned the names of people who had passed away, effectively tuning them into tombstones. Working with the MMTW drew out Beatriz’s substantial talents as a performer and triggered her to write about the process of making this work, which inspired others to be attentive to the way we weave a “ground” of relationships, a “poetics of attachment” that is particularly salient for those who have repeatedly left loved ones behind. It also provided an embodied method, a mode of reaching beyond the comfort zone of one’s habitual artistic practice that came to be central to the MMTW’s experiments.

Her ongoing work with the MMTW has continued to examine how individuals and relationships compose environments, with a composition of floating “faces” contrasted to antique busts at the Allard Pierson Museum, and a reflection on how walls are composed of the eyes of others for Berlin. (figures 4,5).

Blanca Casa Brullet joined the MMTW at its second workshop in November 2013 at the Pavillon Vendome Center for Contemporary Art, in Clichy France. Her “Batgages” (figure 6) was featured in the exhibition at the center, curated by Guillaume Lasserre (also an MMTW member). In Clichy, we included her work composed in paper and helium as part of a group performance (figure 7). In 2014 she began a series of works using actual plaid plastic bags and weeds and soil as her media. In 2014, for the Allard Pierson Museum, she developed a mobile installation that brought “invasive species” into the museum and into her performance. The children in the audience christened her “the plant lady” (figure 8). She embraced that role in several other venues, transporting seedling across the Atlantic and through customs to California in 2016, and explored her feelings of being like a “Mala Madre” plant (bad mother) when she moved her children from Paris to Barcelona at a performance in Paris later that year.

For Blanca, “The workshops are a space of experiment, very free, where the view of the others is essential for redirecting personal work and ideas. By entering into the cooperative work, one’s own work is redirected- the moment of self-abandonment is essential. For me, the MMTW has led me to return to older projects which in the collective context take on new meanings. The work of the workshops also informs my personal work, in some cases, like the work with weeds, this influence is visible in a work I exhibited in a recent solo exhibition (figure 9).

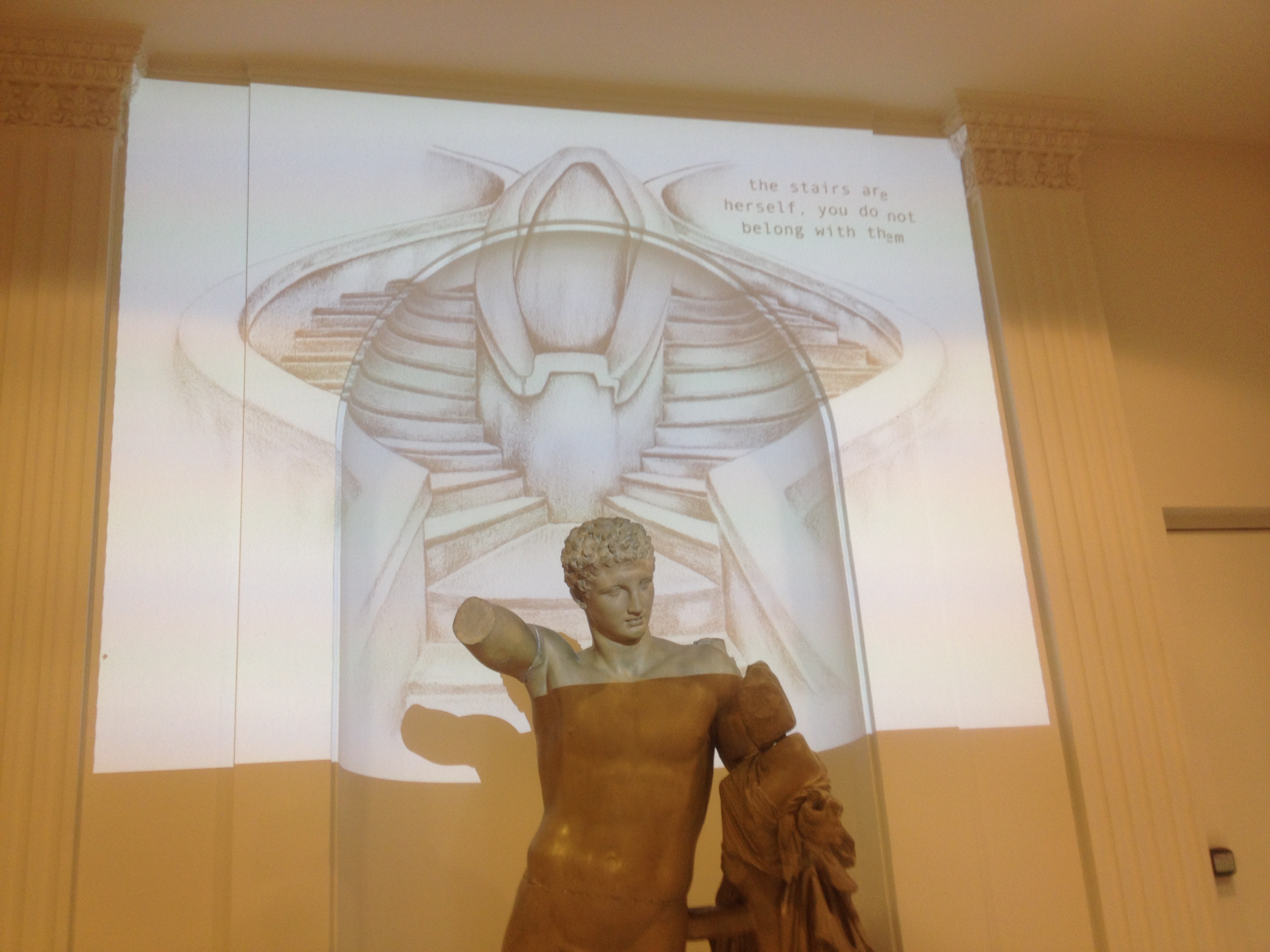

Kayde Anobile joined the MMTW in Amsterdam, where she teamed with Alec Balasescu to projecting images and texts of “ordinary life” in her now home town, Istanbul, onto ancient statues, bringing the ordinary, the quotidian into the museum to probe questions of value and the value of the ephemeral (figure 10).[1]

[1] The collaboration with Kayde led to “The City. One Day,” an illustrated novel that has yet to be published.

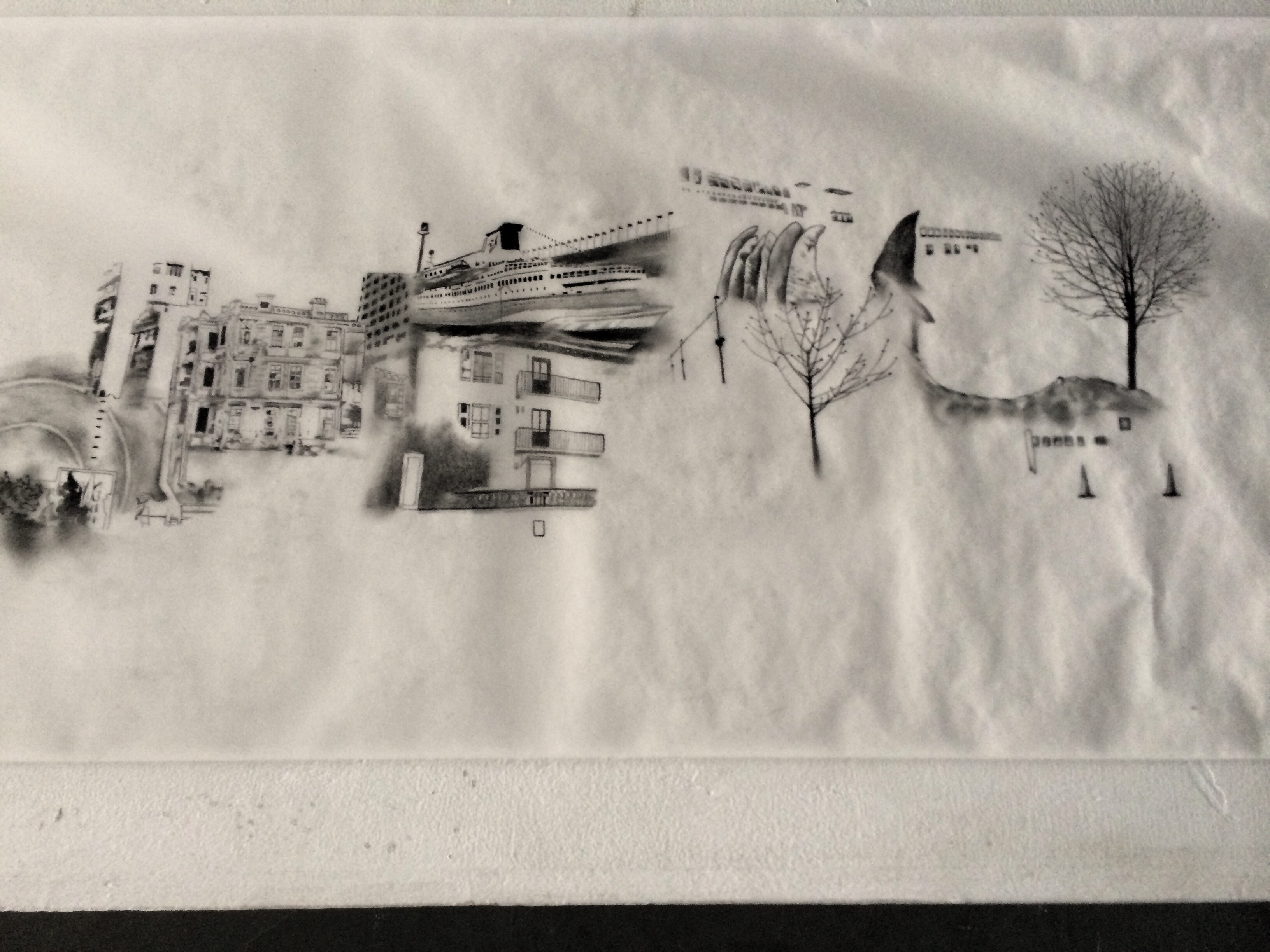

Kayde says that “the anxiety” of the MMTW workshop “migration” situation motivates you to do particular kinds of work or experiments (or not). It has motivated me to do work centered on what I currently call home.” She pursued work that integrated images of Istanbul with images of voyages for the 2015 Bucharest show (figure 11 ). This led to further work as a “serial migrant” for her “Home/Not Home” solo exhibition at London’s Tintype gallery. That show grouped paintings of abandoned Istanbul buildings around an installation in which the concept of home is reduced to its basic elements (figure 12). “Breach,“ which she made for MMTW Berlin in 2017, follows up on this more abstract vein (figure 13).

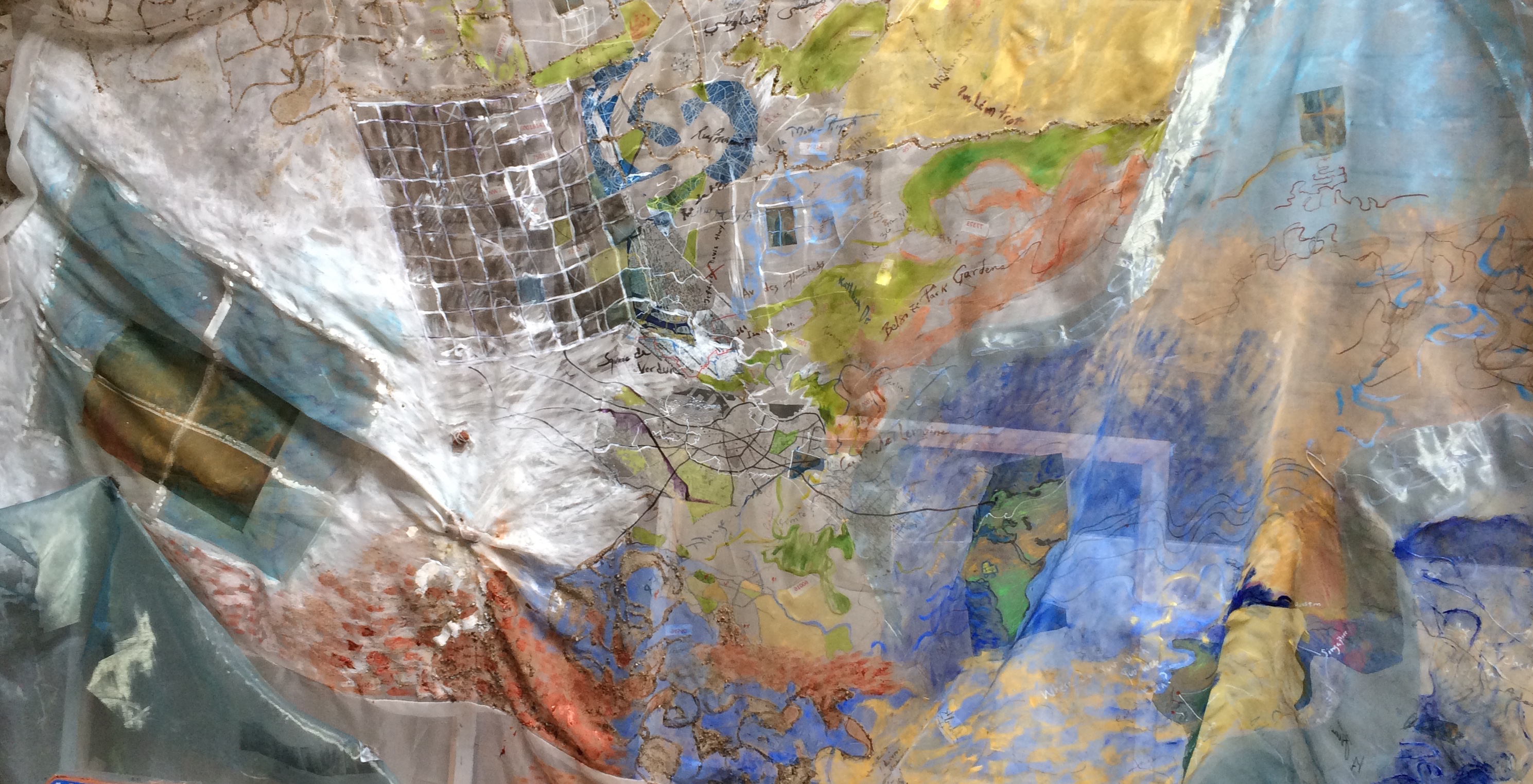

Kayde also filmed the first rendition of the ongoing “Mapquest” project in Bucharest. Alec Balascscu was the principal organizer of that workshop that looked at the relationship of individual life stories to History in a gallery that formerly housed the printing presses of the Ceausescu regime (figure 14). “Mapquest” is a participatory piece which he sees as a kind of “flag” of the MMTW. “It is an emotional mapping of the workshop and the lives its touches,” he writes.

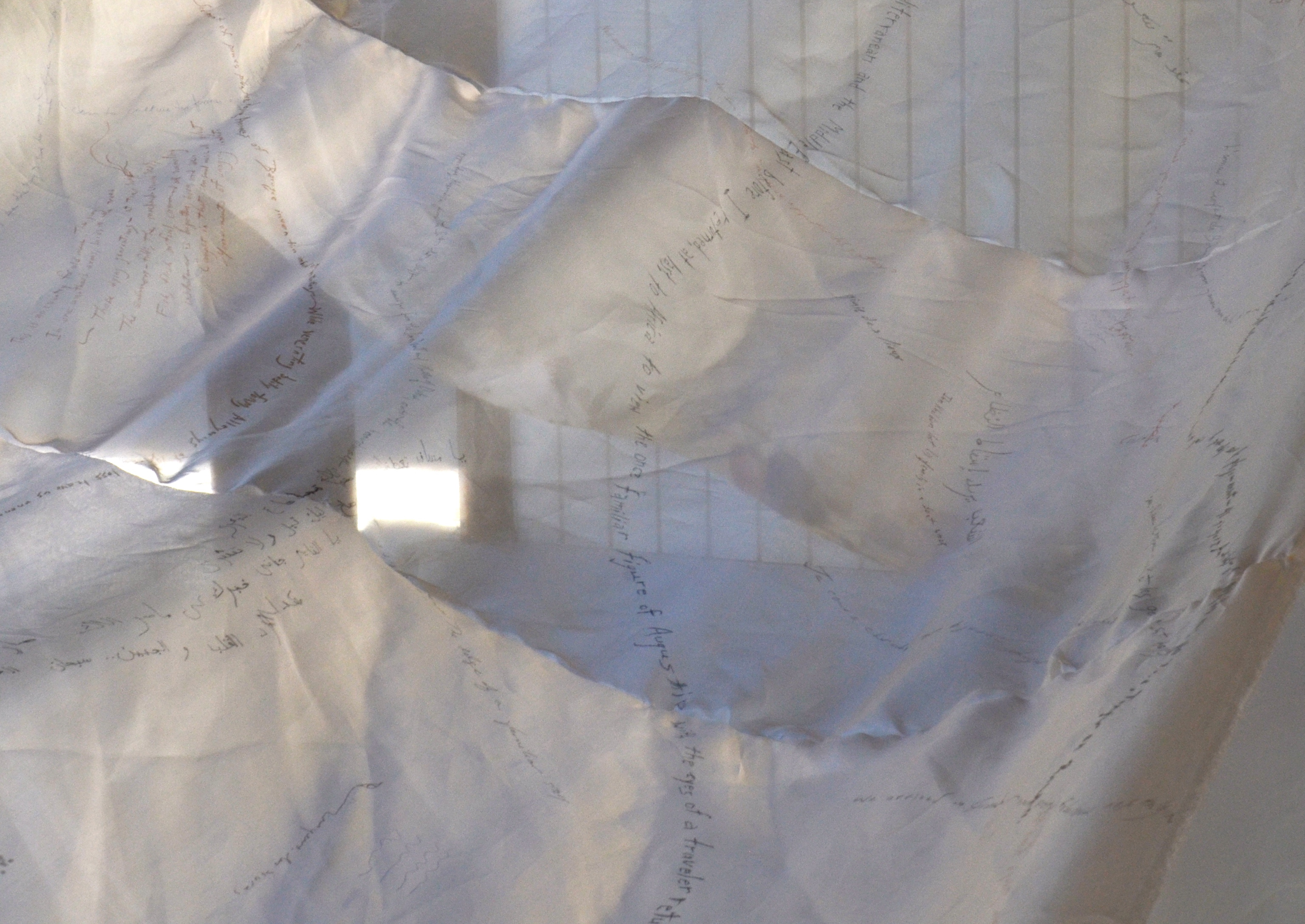

Particular sites are especially meaningful for individual MMTW participants. This was the case for me at the Allard Pierson Museum because the Mediterranean has been a central figure in my work, artistic, academic and personal. With “My Mediterranean Sea Scroll,” I drew together ideas of pan-Mediterranean culture and lived realities of war and disaccord, conquest and colonialism in the region. I made what looks like a sail into a scroll by inscribing authoritative texts on its surface, adding “rolls” beneath the script that included barely visible names of people lost at sea, forgotten by history and replicas of meaningful personal objects I associate with the region that will never be in a museum (figure 15). Burnt matches reference the “burning” of the haraga, those who “incinerate” everything to take their chances in flimsy boats headed to European shores. When the piece is hung horizontally, the objects and names tend to cluster together, sometimes suggesting bodies (figure 16). Its surface and contents are meant to be examined and read- but this requires getting up quite close and even touching the work: many museum visitors felt inhibited about touching. (figure 17)

Like all MMTW art, the scroll was conceived to be portable and adaptable. I developed a second version for Bucharest in 2015. The second version of the piece was hung vertically to facilitate a clearer reading of its contents, a central image of my friend Nabiha taking a photograph of graffiti on the wall of Tunis shortly after the 2011 Revolution which dominates this reflection on history and life story and witnessing. Here, the silky words suggest a fluid, layered context for events rather than a veil (figure 18). A third version for a Riverside, California exhibition in 2016 is ever more intimate. It included images of me and my son in the 1990’s, when divorce and unemployment forced us to live in different countries for several years (figure 19). I think that his biographic turn was possible for me thanks to the sense of security the MMTW created.

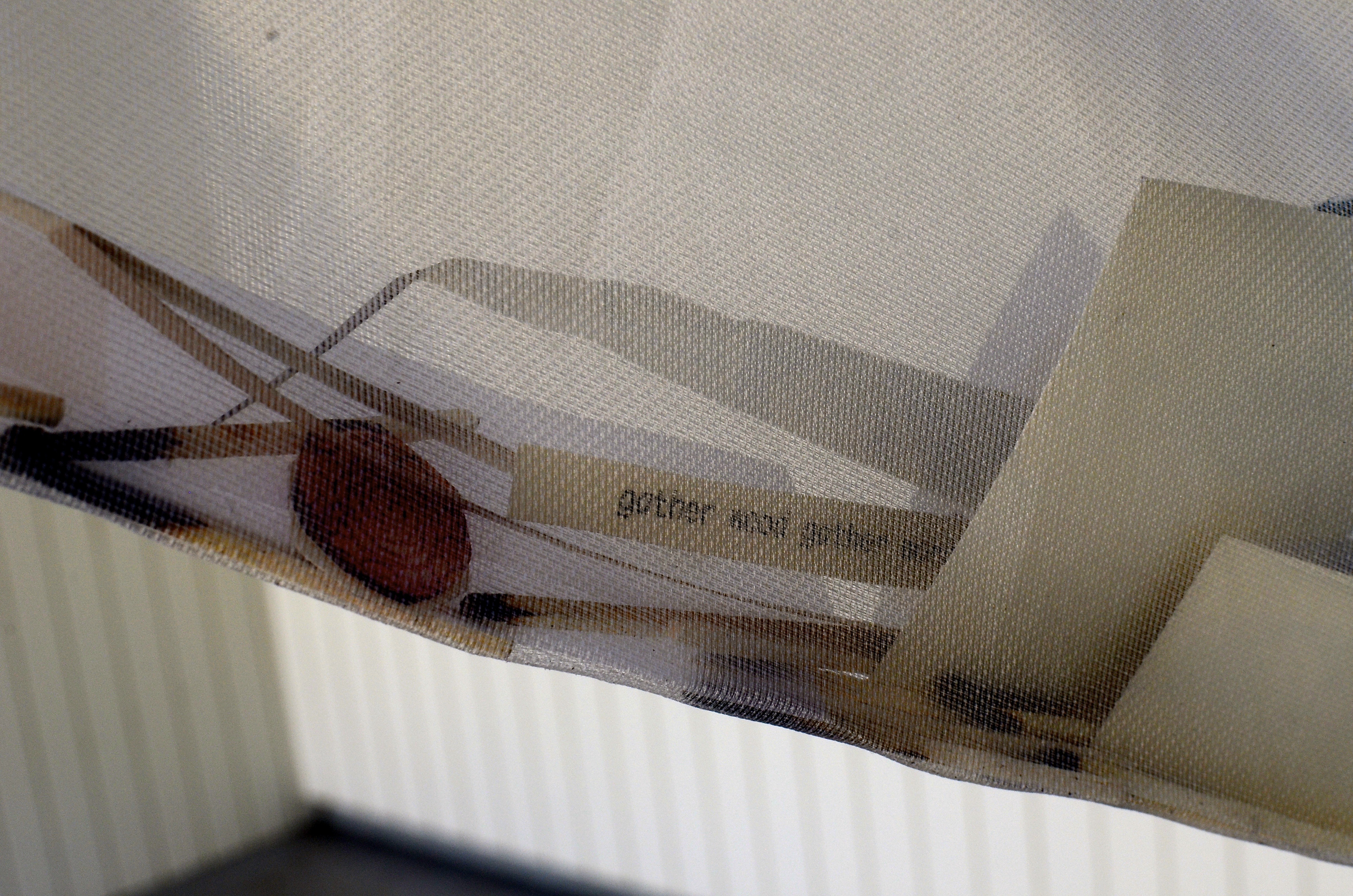

For the 2017 Berlin “Walls” exhibition, I again worked with silk, this time using it as a ground for sand, brick, mortar, pebbles and paint: the stuff of walls. Similar Beatriz’s lists of the names of people in her Mi Tiempo, Mein Raum, My Map, the piece includes every address where I had lived for more than 2 months, my id numbers and passport numbers and social security numbers. These were extremely varied, yet locatable homes and registered identities. The translucent silk revealed the structure of the building and the city; I covered a “window” bordered by a list of the passport hierarchy with a “curtain” that shifted with the wind, revealing a green field beyond. The fabric absorbed dust and pollution, changing color over the month-long exhibition, as though this diaphanous reflection on walls as sources of meaning gained in substance from living in the Kapelle (figure 20).

[1] See Ossman, Susan, Moving Matters, Paths of Serial Migration, Stanford 2013.

[2] The MMTW is administered from the University of California, Riverside and the University of Amsterdam. Its funding comes from grants, funds provided by partners in each site, and private donations.