An introduction to our special feature on Anxiety Culture.

We often see the world’s most pressing and seemingly intractable problems presented through the lens of crisis. But the challenges of climate change, pandemics, mental illness, rapid technological change and its impact on work and individual freedom, migration and its social and political consequences are not always best understood under the prism of “crisis.” Rather, they seep into our collective consciousness, building on an increased sense of insecurity and powerlessness and shaping our relationships with others and the world. Fear of immediate danger has been replaced by anxiety over an uncertain future and shapeless though imminent catastrophes.

What new conceptual framework is needed in order to capture and analyze this era of “anxiety culture”? How can such an analysis lead to a more accurate understanding of the long-term challenges the world is facing today? How can this framework of understanding deliver potential solutions and courses of action that can help mitigate those challenges by empowering both policy makers and civil society actors?

In order to address these questions, the “Anxiety Culture” project draws on international academic expertise in the following key areas:

Climate Change – How can we find a language that does not fixate on the most apocalyptic of scenarios, which instead of serving as a catalyst to action often has the opposite effect of producing political paralysis and a feeling of profound disempowerment? How has climate change altered different areas of cultural and artistic production? What are the conditions for an informed debate that builds bridges between communities of knowledge, policy makers and the general public, over climate change? How can we speak about a future – as parents, politicians, educators, or citizens – so permeated by instability and uncertainty?

Population Health and Social Well Being – A broad range of interacting behavioral, genetic and environmental factors are now believed to constitute risk factors for anxiety. At the individual level, there is mounting evidence that the persistence of anxiety over time can have deleterious effects on human physiology. At a population level, epidemiologically, anxiety may also be related to a broadening range of vexing disorders that now appear to influence the health of populations and, in some cases, approach epidemic proportions. How can interdisciplinary research support the development of a more accurate understanding of the effects of anxiety at both the individual and collective level? How can it build knowledge on the long-term impact of anxiety on educational, developmental and health outcomes?

Migration and the Challenge of Building Social Balance – In the last few decades, we have seen migratory crises triggered by wars, civil conflicts, economic instability, environmental catastrophes and famine. In such crises, migrants are the victims, often struggling with challenges in their new locations that equal or exceed those which they fled. Anxiety also afflicts host communities, generating fears of job losses and xenophobic attitudes. How is a society’s perception of migrants and migration shaped by different forms of public discourse, particularly in the media and on the political stage? How do tensions between national identity and the recognition of socio-cultural diversity play out? What are the long-term consequences of the disjunction between policy formulations and public perceptions of migration?

Technology and its Discontents – A dominant phenomenon that cuts across the transformations of climate change, global health and migration is technology. While technology spurs progress, efficiency and innovation, it also brings profound, often unforeseen changes in the lives of individuals, transforming the way we learn, work, engage with our communities, and project in the future. There is, in the first place, the looming perspective of a workplace radically transformed by technology: the fear that automation, artificial intelligence and “deep learning” will make many jobs redundant. Second, technological progress brings specific threats to personal freedom. Never before has so much data on individuals been held in the hands of corporate entities. This carries long‐term risks, particularly as the means of using this information become more potent. Finally, technology has a deep impact on culture and ways in which individuals relate to their groups. Social media is transforming ways in which we communicate, changing the way we engage with our community, build our self‐esteem and construct our future. How can these sources of anxiety be overcome? And beyond the threats they generate, can they be harnessed to create different social models and build new political projects?

The introductory article “Anxiety Culture: The New Global State of Human Affairs?,” written by the co-founders of the Project, provides a brief historical analysis of “anxiety culture” and highlights the fact that, while anxiety is not born in the present, the current state of anxiety is born out of permanent sense of crisis. The researchers argue for a “middle range theorizing” by seeking to understand how fear is perceived in the contemporary world and in a “risk society” by looking, among others, at educative processes in public institutions.

Jordi Torrent’s work “Anxiety in our Times” provides a historical overview of the human state of anxiety, from Kierkegaard to Miller Beard, from Freud to Watts as well as Canetti. Torrent’s research reveals that anxiety dominates modern societies, particularly in the United States where 42 million Americans suffer from the condition, a situation exacerbated by contemporary media. Torrent’s findings compare social media addiction to that of gambling with long-term negative influences on people’s psychological health and well-being.

In his paper “Anxiety and the Contestation of the Liberal Order,” Thomas Henoekl interrogates the rise in nationalist discourses as a symptom of the public’s fear of current political and economic paradigms. With nationalism creating both a nostalgia for a nationalist past and an aversion towards the mechanisms of flexibility and adaptation as means for addressing contemporary problems, many citizens have come to believe that the European Union has failed to live up to its core pledges. Consequently, European unity and even its legitimacy is being fundamentally questioned by its own citizenry.

Liya Yu’s work “The Irresolvable Political Brain: Our Neuropolitical Limitations in Hyperdiverse and Uncertain Societies” argues that our brains might not be able to handle many of the challenges associated with liberal democratic procedures and that, due to the very limitations of our brains, we might not be able to solve pressing global issues. Yu, thus, sees the need for a neuropolitical perspective to discuss anxiety culture and to understand the neuropolitical conditions of individuals in society in terms of their adaptability to social change on the one hand, and the inescapability of certain hardwired cognitive abilities on the other.

In their article “Do Our Concepts of Bilingual Education Match the Anxieties of Migrants?” Bàrbará Roviró and Patricia Martínez-Álvares analyze the specific anxieties related to the parenting experience of migrant families. The authors highlight the difficult educational decisions parents have to make and explore models of bilingual education that can help respond to families’ anxieties in their efforts to achieve rootedness in their host country while at the same time maintaining their commitment to their cultural identity.

In their article “Migration, Europe and Staged-affect Scenarios,” Paul Mecheril and Monica van der Haagen-Wulff analyze how ‘affect functions’, language and knowledge production in Europe contribute to the construction of the ‘others’, shaping the relationship with migrants as one of domination and demonization. In a context where migration is both a source of disquiet and the subject of political and day-to-day conflicts, they demonstrate how the ‘othering’ of migrants serves as a tool for the denial of colonial responsibility and enshrines the positive self-image of Europe.

In “Robotics and Emotion,” Stephan Habscheid, Christine Hrncal und Rainer Wieching explore how new technologies result in unforeseeable changes in people’s lives. In the anxieties concerning humans being replaced by machines, the authors study authentic interactions emerging from the use of robots in nursing homes.

In his article “Origins and Structure of Anxiety about Technology,” Raphaël Liogier offers a genealogy of the idea of technological progress and analyzes three sources of technology-fueled anxiety: 1. the fear of technology’s domination and destructive power; 2. the excessive power that technology offers mankind and the sense of hubris this generates; and 3. the deep concern that technology will threaten human professions, activities and sense of purpose. Liogier further identifies trends that enhance “anxiety culture,” including technological advances that fundamentally change the nature of relations between human beings and their environment.

In “Toward a Strengths-Based Approach to Mitigating our Anxiety Culture,” Beatrice L. Bridglall discusses the importance of a planetary awareness of nine climate thresholds and proposes that we discuss the accelerating climate challenge from a resiliency/resilience dividend perspective. Bridglall then sheds light on how the Netherlands is rethinking its handling of rising sea levels and other climate change impacts, thereby realizing the resilience dividend. She also discusses how the methods that the Dutch are using to manage climate change strengthen their social resilience as well.

Sandra Ponzanesi’s work “Digital Strangers at Our Door: Moral Panic and the Refugee Crisis” highlights the dichotomy between technology’s ability to offer new opportunities for diasporic communities to stay connected and the new sources of anxiety and resistance created by the speed, uncontrollability and unpredictability of these flows generated by these “digital strangers” at our door.

In “Elective Anxieties: Migrating Art with the Moving Matters Traveling Workshop,” Susan Ossman examines the workshop founded by a small group of serial migrant artists and scholars in 2013. The group successfully integrated sciences with the arts by bringing together dancers, writers, painters and social scientists, all of whom transgress boundaries of their own discipline/occupation to confront anxiety and angst with the task of developing art on migration and mobility.

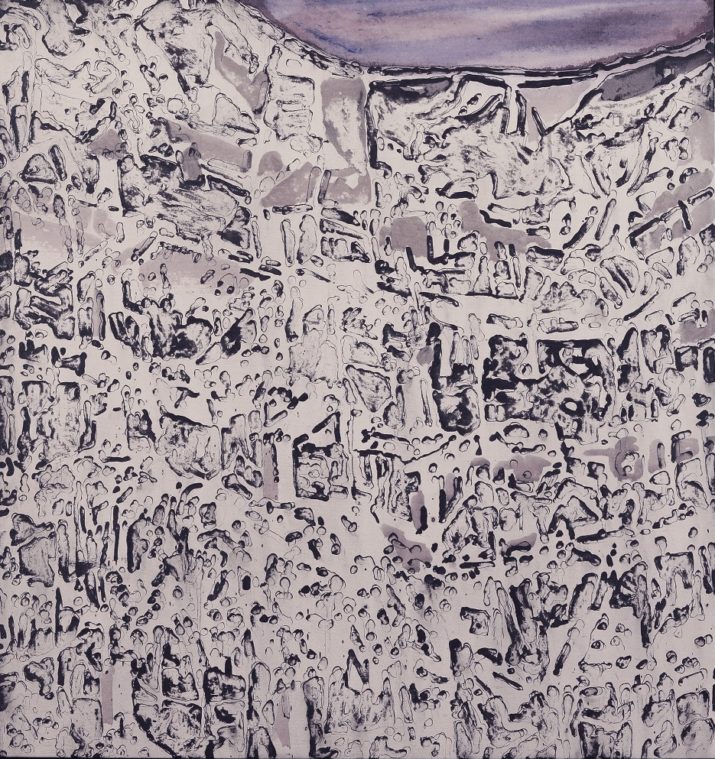

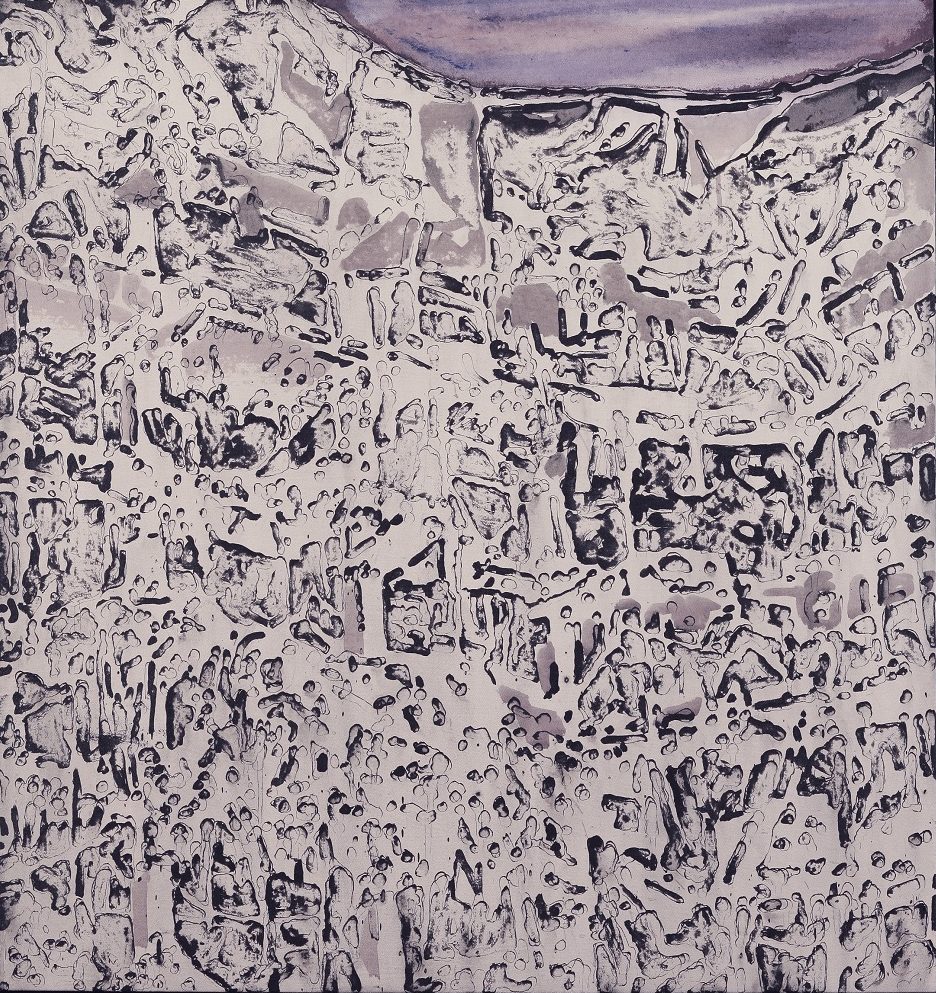

Through the works of renowned artists Kim Noble and Jorge Tacla, the art series “Hands Tied” tackles questions of identity and the throes of mental illness, ultimately illustrating the beauty that can be discovered. Diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder at age fourteen, Noble has learned to cope with her anxieties through painting. Tacla’s paintings focus on a different kind of anxiety—that kind that arises in the wake of calamity, either natural or man-made. Specifically, his works frequently involve devastated Chilean architecture, representing a “space of social rupture.”

“Governance of sustainable growth” is how the Eucor research alliance refers to its overarching theme, enveloping five profile areas: governance, power and infrastructure, societal change and innovation, resource management, and issues surrounding multiculturalism and multilingualism in sustainable development. Campus is introducing this remarkable alliance here.

Nicole Shea is the Director of the Council for European Studies at Columbia University and the Executive Editor of EuropeNow.

Emmanuel Kattan is the Director of the Alliance Program. He was previously Director of the British Council in New York, where he oversaw academic collaboration programs.

Research

– “Anxiety in Our Times” by Jordi Torrent

– “Anxiety and the Contestation of the Liberal Order” by Thomas Henökl

– “Digital Strangers at Our Door: Moral Panic and the Refugee Crisis” by Sandra Ponzanesi

– “Toward a Strengths-Based Approach to Mitigating our Anxiety Culture” by Beatrice L. Bridglall

– “Migration, Europe, and Staged Affect-Scenarios” by Paul Mecheril and Monica van der Haagen-Wulff

– “Origins and Structure of Anxiety Culture over Technology” by Raphaël Liogier

Visual Art

– “Hands Tied,” an art series curated by Kayla Maiuri and Nicole Shea

– “Elective Anxieties: Migrating Art with the Moving Matters Traveling Workshop” by Susan Ossman

Reviews

– The Construction of Equality Syriac Immigration and the Swedish City, reviewed by Ada Engebrigtsen

Campus Spotlight: Eucor

– “On the Path to a European University” by Janosch Nieden

Poetry

– Excerpt from Middlemost Constantine by Ken White

– Excerpt from Imaginary Explosions by Caitlin Berrigan

Fiction

– Excerpt from Hunting Party by Agnes Desarthe, translated from the French by Christiana Hills

– Excerpt from The Storm by Tomás González, translated from the Spanish by Andrea Rosenberg

Nonfiction

– “Making Spain Great Again” by Layla Benitez-James

Photo: Rubble 17 by Jorge Tacla

Published on July 2, 2018.