Translated from the Norwegian Julia Johanne Tolo.

This is part of our special feature, New Nordic Voices.

SK1497

This is the globe. It’s blue, with green, orange, and yellow sections. Sometimes pink or red. It turns in the dark, and has two white spots. The North Pole and the South Pole. If you want to leave the globe you have to send an application to somewhere like NASA, and you’ll need to be good at physics, math, and chemistry. It’s a long process, you should have started planning a long time ago. It might already be too late. If you made your own rocket, in your backyard, with your own money, you’d still have to apply in order to shoot it up. You’d probably receive a rejection letter, that’s just how it is. People can’t shoot themselves up in rockets whenever they feel like it. If I put my thumb where it says Oslo and stretch my hand out, there’s exactly thirteen centimeter to Moscow, eight to London, four to Stockholm. I turn the globe around one more time, pull out the plug and throw it in a Goodwill container.

The last night before I leave, I say goodbye to everyone at a bar. We drink to me, to Paris and I wonder why I’m leaving this. My life here is so good. The bike rides to Huk in the late summer, the light in Bjerregaards street in the morning, the electronic music that pounds in us on Thursday, Friday and Saturday night. Ending up at Café Sara drinking beer, rather than standing in line at Blå. Him. I’ve tried to write a list of reasons to stay/go, but it evens out every time. I bike home to Tøyen for the last time this summer, through Jens Bjelkes street and past the Botanical Garden. I lock myself into the empty apartment and finish packing. I’ve said goodbye to everyone, bought travel insurance and a dictionary. I took the pictures off the wall, wrapped them safely in newspaper and put them in my suitcase, so I have something to put on the wall when I arrive. It doesn’t take long to pack away everything you own. A couple of days, maybe. Seven cardboard boxes in the corner and two garbage bags in the hallway. One of my two suitcases is by my bed, I wish one of them were his, but they’re both mine.

– Did you know the earth rotates at 1675 kilometers an hour? I say I didn’t know, I can’t feel it. I move my hand through the air, trying to feel the speed. He says we move one kilometer through the universe in two seconds. I count till two, still can’t feel it. He tells me our DNA will never again be exactly here, in this place in the universe. We’ve already travelled many kilometers, just in the seconds we spent talking about it. Tomorrow we’ll be even further away. I say good night. He falls asleep right after, I can feel every little twitch in his body, the heavy breaths, heavier and slower with every second. We’re on a mattress on a floor at Tøyen, 13.7 billion years after the universe was created. We are here now and never again.

An airport is a place where time disappears. I take off my jacket in the security check and walk through the metal detector. While I do this, I think of nothing, and I let two hours pass while I wait for my flight. I can’t read, I stay sitting on the same bench watching the planes land and take off. Stewardesses with gloves and updos walk by. Maybe my suitcases will disappear, one time has to be the first. I wait. Turn off my phone. Flip through my passport. Look at my picture, I have wet hair and sleepy eyes. It’s a very unfortunate picture, but it does the job. At the airport it’s called boarding pass, not ticket. That seems more formal. You act different, it’s a different country with its own rules, first you take off watches and belts in security, then you shop for liquor and perfume in duty free. Everyone does it. The moment I sit down in the plane, I fall asleep, and I don’t wake up until we are far above the clouds. I’m like Dorothy on the way to Oz, can’t imagine what’s in store for me, what was I thinking? I thought of magnolia blossoms in April, about how the Louvre is almost deserted in February and about nuns jogging up the stairs of Montmartre in white sneakers, I dreamed of Paris, of sleeping on a mattress on the floor and smoking in a café. Black turtlenecks, Jardin du Luxembourg, Notre Dame. Things I’ve heard of, things I’ve imagined. I thought about doing that year abroad, after I finished school, the year everyone dreams of. What those who go to bike along the canals in Amsterdam dream of, those who spend a year saving up to go surfing in Australia, those who get letters in the mail that they finally got into Oxford, those who do ex.phil at Bali and drink away their student loans, those who move to Copenhagen and never come back, those who travel around the world in 12 months. I turned the globe and my finger hit Paris. It was just a name on a map. A city I had seen in a movie, not too far away, but far enough. This is not a dream, I’m in a 40 ton airplane a thousand feet over the ground and this is where the line is drawn between dream and reality. If I crash, I crash. I chose the window seat, I always have to be by the window, even though I know the aisle is safer. The plane could catch fire. The walls could fall off. Who will be the last person I think of as the plan rushes to the ground? Will I think about all of the nice things we could have done? Robbed a bank. Had a coffee. You could have the globe I bought you for your birthday. I gave it to Goodwill. I didn’t want to give the whole world to someone who didn’t want me.

Paris

Charles de Gaulle

Thai stewardesses in purple uniforms are driving segways alongside the moving walkway I’m on. I can still hear some Norwegian voices around me, but by the time I’ve gotten my suitcases and trundled them out of arrivals, all voices have become French. I look around for others from my flight, but they must have disappeared into the crowd. Not that it matters much where they went to, but now I’m completely alone. It’s still summer here. I take a taxi from Charles de Gaulle Aéroport into Paris. The driver asks me where I’m from, I say Norway and he says ohlala. I end the conversation, lean back in my seat. The air condition gives me goosebumps while we drive through huge industrial areas, past parking lots, factories, and gas stations with trucks up front. None of it makes me think of Paris, not until the freeway comes up along the Seine and I see the buildings getting brighter, wrought iron balconies, corner cafés, all the bridges over the Seine, pharmacies in every roundabout. The taxi driver stops at the address I’ve given him, I pay him in euros and it feels a bit like monopoly money, just colorful pieces of paper. Then I stand outside the building where I am renting a room for the next two weeks, with my two suitcases. I press a code to open the door, 1307, one number for bad luck, one for good luck. I’m surprised when the door opens. I leave the two suitcases in the lobby while I walk up to the fourth floor, find the first door on the left, and open it with the keys I got in the mail. Then I pull one suitcase at a time up the winding staircase. I hear voices behind the other doors. The room I rented from a Swedish student on summer vacation looks more like a cupboard, shower in the right corner, kitchen counter and sink in the left corner, bed by the door, toilet in the hallway. The afternoon sun has made the room burning hot, dust spirals up in the air with every move I make. A group of burnt plants are by the window. I open the door that leads out to a small balcony and all the sounds of Paris come into the room; sirens, people and cars. Here I am. I would like to stay but I run downstairs for the second suitcase, pulling it makes the skin in my palms burn. I lie on the bed and dial grandma’s number, the deal was I call as soon as I arrive. It rings for a long time, maybe she’s in the garden, but right before I’m about to hang up she’s there and the first thing she says is my name, and my stomach is warm from hearing my name being said in grandma’s kitchen. As if it’s being said here, in Paris. I say that I’m here, that everything has gone well, that the weather is nice. The sound of her kitchen radio blends with the sound of a big city in late summer, the warm light, the polluted air, the sweet smell from thousands of bakeries and fruit markets. – I always wanted to go to Paris but it never happened and now it’s too late, grandma says into her receiver, and it’s the end of August, there are apples and plums in the garden, way too much for just one person, and the freezer is full of from last years fruit and from the year before that and the year before that again.

After it ended we went to the movies, because we were going to be friends, that’s a thing you say when it’s over so it won’t seem too sad. He chose the movie, it didn’t matter much to me. While we sat there in the dark I wanted to lean on his shoulder, but I couldn’t, and I couldn’t understand that you say those three words, it is over, and then I can’t lean on his shoulder anymore. We can tear up photographs and tape them back together again, we can fall off our bikes and get five stitches in our forehead, we can even cut into people, open them up and fix what’s wrong inside and sew them back together again and release them from the hospital two days later, but words can’t be unsaid. After the movie we stood outside of Ringen Cinema, he was going up, I was going down, two months ago we would have walked the same way. He asked me if I’d done anything cool lately and I said I was thinking about moving to Paris and then he laughed and asked if I was going to be a cliché and find myself in Paris. And maybe I am, maybe I end up finding myself in a closet, under a bed or in the backseat of a car, but most of all I want to get the hell away from him, that’s what I should have said, and then I should have left, or layed down on the ground, or jumped into a pirate taxi, or broken a window, or thrown a snowball with little rocks in it, or blown up a mailbox, or hit an old woman. But I laughed and I gave him a hug, and then he walked up towards Torshov, and I walked down towards Tøyen, it’s a long time ago now and maybe I shouldn’t still be thinking about it, but I’m thinking about it anyway, and now I’ve left and I’m never coming back.

James Dean

Grandma got married in 1955, the year that James Dean drove himself to his death. He was 24, the same age that I am now. Soon I’ll be older than he ever was. It’s already too late to become an astronaut, a ballerina or a concert pianist. Things you dreamed of when you are little. When I see pictures of my parents in photo albums, life seems so inconceivably long. They’re at parties with groups of friends that don’t exist anymore, I recognize some of the faces, the rest are unfamiliar, friends that drifted further and further away. Grandma said once that Paris is Cupid’s city, even though she’d never been there. She always says that life happens so fast. One day you wake up and see the hands of an old lady on the top of the covers, instead of your own

I wake up when the light in my room is different. I wonder why everything is so gray, why it feels so cold and moist, and then I realize it’s raining on my third day in Paris. The grey–blue light, the light that makes people soft in the face, the light that makes Paris Paris, enters my room and settles on me. I’ve seen this light in black and white pictures from the sixties. If I can even call it light, it feels so flat, without direction. It doesn’t make me want to get up, and I pull the warm covers around me and fall back asleep. When I wake up two hours later, it’s twelve. The light is the same, and I am still here, in Paris. I boil two eggs, soft, as always, but I can only eat one, because they’re different than what I’m used to. It makes me feel a bit homesick. The coffee cups are so tiny. The hosts on the radio shows speak so quickly. The people I see in the street have narrow faces and tiny, shiny shoes. It’s not wrong, just different. I lie on the bed, and start practicing numbers. I count in French: une, deux, trois, quatre, first I practice all the numbers up to fifty, then to one hundred, I count louder and louder, faster and faster. I can hear the neighbor moving around on the other side of the thin wall, he must think I’m crazy, or maybe he doesn’t think much about it, maybe he shrugs and curses in French. He’s probably experienced this before, that a Norwegian girl counts to herself loudly in bed. How many people must have done this before? How many people come to Paris, lie on the bed, learn how to count, find friends, work, and a black coat? After counting to one hundred a few times I get dressed and go to get something to eat. When I get outside I realize I don’t have an umbrella, when I was packing I forgot to consider that it rains in Paris. It does rain in Paris, I know because my shoes are getting wet and my hair is sticking to my face, but I keep walking down boulevard Richard–Lenoir to find someplace where I can buy an umbrella. I walk past a butcher and a fishmonger, they have different kinds of fish here, my eyes try to find the kinds of fish I know, but no,I run down the boulevard in the rain to find an umbrella. In the end I find a metro station. I go underground. I take line number 9 in a random direction and get off at a stop called République, where everyone else in my cart get off. République is one big roundabout, and at one of the chain stores that are scattered around I find an umbrella. Even though I’m soaked into my skin I open the umbrella, and I buy a crepe with nutella that I eat under my umbrella. I look at a map and find out that I’m not so far from home, so I skip the metro and walk, to get familiar. When I am back in the room where I live I put on warm stockings and a wool sweater and lie on the bed to look up the word for umbrella in the dictionary. Parapluie. At night I pull a chair up to the big window, open a bottle of wine, and make ravioli with cheese. The sun goes down, the city comes on. Anything I can dream of is out there. I think about being thirteen-fourteen years old, outside of my window I see the forest, and when it gets dark I feel lonely. There’s nowhere to go, because you don’t go out into the woods alone at night. And as I look out a window in Paris, almost ten years later, I get the same feeling of not being able to go anywhere, because I don’t know anyone and because I am afraid of the city at night, just like the woods. So I feel a bit lonely, at least alone, and I regret coming, just a bit. I tell myself I have to stick it out. As if it’s the first day of school in tenth grade, I look at the twenty-four faces around me that I only have to endure for one more year, before I’m free, but then there’s high school with even more things to deal with, and I think that in three years I’ll be free, but I have to study, everyone has to study, and after that I’m free, I can go abroad, and I go abroad even though I’m not sure that I want to, but I don’t want to work, I’ll be working the rest of my life. And no matter what I do, if I go to the city or a small town, I’m still me, and I feel lonely when I’m alone. Like here, in Paris with millions of people around me, or when I was fourteen in a small town, but maybe most of all I was lonely in his twin size bed at Torshov in Oslo.

Benedikte

Me and Benedikte, we have known each other since we were little seeds. Or at least since we were thirteen, and started in the same class. One time I needed stitches in my hand, I was nineteen, and Benedikte walked me to the emergency room. I had slipped on a rock by the ocean, and it was summer. The rest of the summer I had to hold my hand up from the water whenever we went swimming, and I got a long scar in my palm. I wrote her down as my emergency contact in the form I got at the emergency room, she was the one that knew me the best, and the other way around. It felt so adult to put someone other than your parents, but we saw each other every single day. It was the two of us, Benedikte was my emergency contact, and I was hers. We talk on Skype, I bring the laptop onto the balcony and turn the camera towards the city. – Can you see? I ask. Benedikte knows exactly what grandma’s house looks like, exactly what the scar in my palm looks like, and how I looked when I was 13 with large front teeth and skinny arms. No one in Paris knows that. And I don’t know how far away from each other you can be before you stop being each other’s emergency contact.

Anna

With my map unfolded on the café table at the corner café in rue St. Antoine, I look for an apartment in newspapers I don’t understand. With my new French phone number I call unusually long numbers, speak English, schedule showings, Montmartre, Bastille and St. Germaine. I make a little blue dot on the map just on the corner where I’m sitting, and from there I draw lines to the places I’m visiting, with a blue pen, and with a red pen I draw lines to the places I’ve already been. I put numbers on all the blue lines and decide to begin with line number one. The first apartment I’m seeing is in 5 Boulevard de Rochechouart, and when I come up to the street from the metro, there are so many people on the boulevard moving in different directions around me that I almost can’t make my way through. If I were to draw all these people as dots on the map, and give every single one their own lines with the places they had been, the map would be covered in ink, there wouldn’t be room for anything but ink on ink. I think that I have to stop thinking like that, I have to stop thinking that I live in the same city as 2 153 599 other people, I have to stop thinking that I think the coffee here is bad. I make my way to house number five and ring the doorbell that says Lèfevbre. The man called Lèfevbre shows me the room he is renting, kitchen in the corner, street view, toilet in the hall, shower behind the door. His English is bad and I have to take out my notepad to draw, explain, and write, and the more I explain, the less he understands. He takes my notepad and writes 500 and votre dernière fiche de paie and ? I look at him and show him I don’t understand and he says non, non, non and shows me out. When I come back outside to the street, two million people pass me by. I push my way down the boulevard, take a deep breath and dive back down into the metro system one more time, close my eyes as soon as I sit down and decide to delete this day. When I lock myself into my room I find my Norwegian sim-card to call home. When I turn on my phone, there’s a message from a Norwegian girl who’s seen my ad at the Seaman’s church. I clear my throat three times and call her right away. We plan to meet at place George Pompidou the next day, and I take out the map and draw a blue dot at the address that she told me and write “Anna” next to it.

In 30 square meters of space on the sixth floor, in 26 rue Rochebrune, I move in with Anna, who’s lived in Paris as long as me. She’s Norwegian, but she looks French and when we walk down the street I can feel us fitting in, if you saw us from afar we could be two French girls, one light and one dark, if you didn’t hear that we were talking loudly in a sing-song language, if you didn’t notice that we were a bit taller than the other girls. We live at the top. All of the cheap, little apartments are at the top. It feels like we’re walking on the roof, over the city. I take a picture of the view from the balcony. The area we live in, the 11 arrondissement, is never quiet. The first night I wake from all the sounds from the building, and from the street. –150 000 people live right here in the 11 arrondissement, Anna says. –Is that true? I look down on the street from the balcony. One hundred and fifty thousand neighbors. The balcony faces out towards rue St. Maur, a long street full of people, dogs, cars, restaurants, bakeries, pharmacies, discotheques. I have never gotten to know anyone as quickly as Anna. Maybe because we have to, maybe because the apartment is so small, or because it feels so good to get to talk Norwegian to each other at the end of the day. We walk down the street, speak Norwegian and laugh so that Anna has to hold her stomach, lean over and sit down on the street. I tell her about going to look at the apartment in 5 Boulevard de Rochechouart, about having to draw on a notepad for a man named Lèfevbre, Anna sits on the pavement and laughs while I stand next to her and then pull her back up. Anna is exactly the same height as me and we stand in front of the mirror at night and brush our teeth in our new apartment. We put in lightbulbs, nail pictures to the wall, remove cobwebs from the ceiling and try to make the apartment with the creaky wooden floors home. James Dean gets to hang over the kitchen table. We go to the market by Porte de Montreuil and haggle for a kitchen table and a steel lamp, we get it down to twenty euro. We bring them home on the metro, even though the other passengers stare. We wash empty jam containers and use them to drink wine from, and we use the wine bottles for candle holders. We hang pictures of our families on the fridge, tell each other about siblings and grandparents. Anna misses the sound of her little brother practicing his skateboard outside the house in the summer. And the snow under the street lights in winter. – There’s no snow in Norway now anyway. – Still miss it, Anna says. On warm nights we bring our thin duvets out on the balcony and read out loud from Beatles, about Oslo, about apple trees and Schweigaards street. In front of us windows light up in many thousand apartments. Anna feels homesick. She drinks coffee from a mug with a picture of her family. It’s nice, even though the picture is pretty blurry. I borrow it sometimes when Anna is at school. I don’t feel homesick, try to long for home, but I’m happy to float through the streets all day. I wonder how long I can go without missing anyone, wonder how long it’s been since I’ve seen the ocean, how long it’ll take before I realize I’ve been between two buildings for over two weeks, that the sky above me is never larger than the street I’m standing in. I take the metro to Tour Montparnasse, take the elevator up the 59 floors, stand by the panorama window and look at the streets I walk through, down there, wave to my window on the other side of the Seine. Up here I’m in control of everything, I watch the cars flow slowly past, I watch the rooftops that form waves towards Montmartre, all of them in the same light colors. In Paris there are no starry skies, for every street light being lit, hundreds of stars disappear for those of us who live here. The Parisians have stopped looking up long ago, I stand out when I look up at the cast iron balconies and when I turn to look at people on the street. I press my forehead against the cool panorama window and look out on the city, I don’t know how long I stay like that, I can’t perceive time when I am alone. All the faces I see on the street just slip by, and no one in the entire world knows I am standing at the top of the second tallest building in Paris.

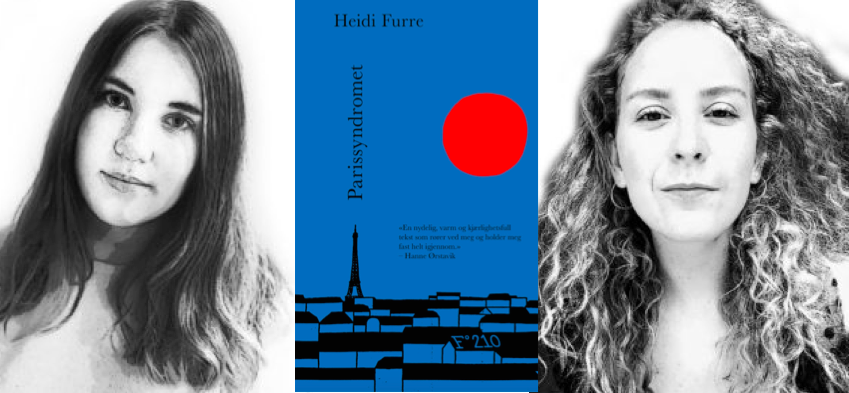

Julia Johanne Tolo is a poet and translator from Oslo, Norway. She is the author of August, and the snow has just melted, from Bottlecap Press. Recent work has been featured in or is forthcoming from No, Dear, Copper Nickel Journal, Brooklyn Rail, Ghost City Review, Slice Magazine, and Seventh Wave.

Heidi Furre (born November 6, 1986) is a Norwegian writer. Furre debuted in 2013 with the novel Parissyndromet, and later published Ungdomsskulen (2016). She also works as a photographer next to the writing. Furre originally comes from Stord, and lives in Oslo.

Published on April 17, 2018.