This is part of our special feature, New Nordic Voices.

During the last couple of years, I have had the privilege to work alongside Canadian-Icelandic poet and artist Angela Rawlings as both an editor and a curator, experiencing first hand the brilliance, commitment and utmost kindness she brings to everything she does. Our collaborations have played out from poetry readings at small, crowded Berlin art spaces to meditative performances of endurance on Norwegian foreshores. Rawlings has generously (and patiently) accepted my sometimes ludicrous curatorial suggestions, such as reading poetry to a stressed-out chestnut tree at the Danish music festival Roskilde Festival (followed by a tarot session for the tree), auditioning to marry a frog and sharing bacteria with a so called SCOBY, during an impromptu kombucha ritual. Our conversations have sprouted around questions of more-than-human poetics and the im/possibilities of co-authoring with nonhuman entities such as animals, waters, currents, landscapes.

—Ida Bencke for EuropeNow

EuropeNow Your practice — whether poetic, artistic or academic — is radically multi- or interdisciplinary and deeply experimental. What I find especially striking about your work is how it animates and activates bodies in various ways: through pleasure, shock, movement. You attempt to enter into conversations with precarious non-human others, such as polluted landscapes through embodied encounters always deeply entangled in languages(s). Can you tell me a little bit about the role different kinds of bodies play in your work, and their relation to language and knowledge?

Visual poem excerpted from Gibber. Credit: Angela Rawlings, 2012.

Angela Rawlings I’ll preface my response with two legal precedents that were set within government-run natural resource management frameworks in the past ten years. In 2010, Bolivia introduced its legislature Ley de Derechos de la Madre Tierra (Law of the Rights of Mother Earth), which declared earth and its life-systems as titleholders of inherent rights. In 2017, a Maori community won their case to have the Whanganui River awarded the status of a living entity, which would equate its rights with those of humans under New Zealand law. These legal precedents underscore the rights of more-than-human bodies, coupled with a respect for ecosystems as having their own inherent value beyond what resources they offer humans. This parallels an ecopoethics driving my work, where languaging and relating and bodies and knowledge-building aren’t solely human domain but multi-entity activities.

Are our bodies ours? Possession, in English: a sense of ownership, and/or to be taken over by another… The domination present in the former meaning (to own), the seduction and/or illness inherent in the latter (to be bewitched). How does reconfiguring one’s notion of what a body is help to relate to how bodies co-exist? Who has a body, what constitutes a body, what bodies have what rights?

A mountain as a body, an ecosystem as a body, a bay as a body and an ocean as a body. A virus as a body, a word as a body, a fish as a body, sky as body, body of weather, body of work, body of lake, body of advice, body of knowledge, body of eelgrass, body of mussel, body of river, body of proof, body of egg, body of evidence, fruiting body of mushroom, body of opinion, body of text, human as a body, galaxy as a body.

A structural component of my works Wide slumber for lepidopterists, Echolology and Gibber interrogates how pronoun usage in English has been co-opted into a hierarchical relationship of human and more-than-human bodies. Humans have several pronouns (I, you, he, she, we) while more-than-humans less so (it) unless a more-than-human has been assigned a familiarity with the human uttering it (domestic animals, ships, etc.). Humans are “who’s,” more-than-humans are “what’s.” Is an it or a what with relatable corporeal rights to exist and thrive as a she, we, or who?

EuropeNow As to accommodate different and differentiated bodies, you work across languages, both semantic, symbolic and asemic ones. Can you talk a little but about what multilingualism means to you as a writer, as an artist and as a body living, loving and working across languages?

Caption: Visual poem excerpted from Gibber. Credit: Angela Rawlings, 2012.

Angela Rawlings Multilingualism is a gateway to different perspectives in sensing the world. Even before semantic acquisition of a foreign language, its visual and auditory materials pique curiosity through their sensorial refigurations.

It is instructive for me to circulate where I don’t have immediate linguistic access. Learning other languages helps to expose the interconnectedness of languages to one another, while obviating and challenging the assumptions I’ve made about my mother tongue, English. I’ve found the greatest insights into my own mother tongue when I’ve felt a sense of defamiliarization and enstrangement from that language. In formative years, we learn our first languages through training a mastery, or confidence, in that language. We learn “perfect” spelling and “standardized” grammar. The malleability of our first languages is exposed through the realization that spelling and grammar rules can be bent. This playfulness and flexibility with linguistic structures has extended my confidence to question other seemingly fixed structures that govern everyday life through a process of learning and unlearning.

EuropeNow You have spoken about defamiliarizing yourself from your mother tongue, but in what manner have you been working with foreign languages? A poem that comes to my mind is the one in which you gather all of the words in Danish containing “land,” which I read as a comment on how histories of colonialism resides in- and seeps through our wor(l)ds.

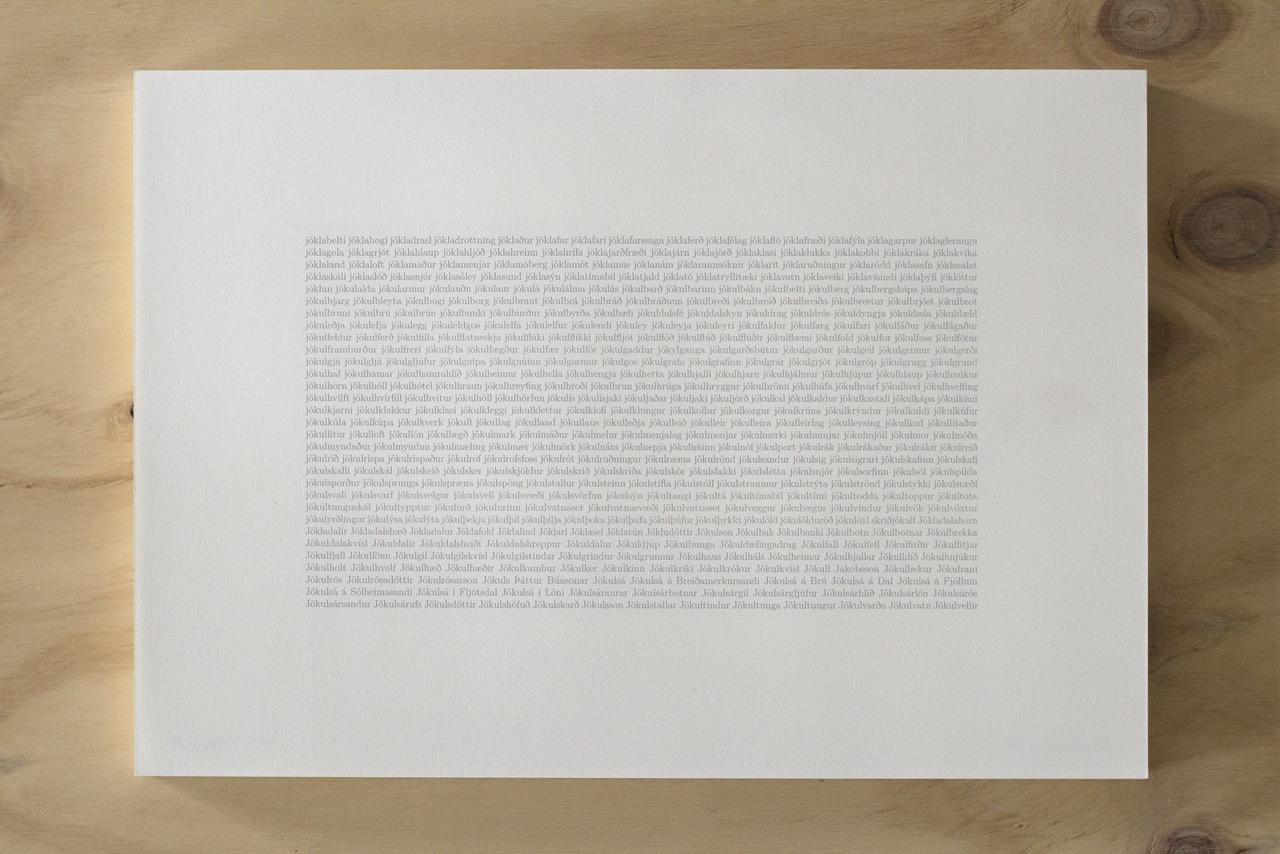

In Memory: Jökull by Angela Rawlings. Credit: Ida Bencke, 2015.

Angela Rawlings In Gibber, I gathered all of the place names in Queensland, Australia that included the word “land” as part of my inquiry into what are the languages currently inscribing this place. There are 1,400 regional place names with “land” embedded in them, names that combined Aboriginal languages with the colonizing English to rewrite places. I printed the names on transparencies and photographed them in several ecosystems throughout Queensland.

The work in Queensland extended to where I reside in Iceland, and I searched for words in Icelandic, English, and Danish that contained “land.” I chose Danish because Iceland is a former colony of Denmark, and Danish is the second or third language acquired in Icelandic schools (alongside Icelandic and English). The lists of lands appear in the forthcoming book Áfall/Trauma, which resituates a body (my body) in relation to land through the experience of cancer treatment. The book, overall, oscillates between English and Icelandic.

More recently, I gathered terms within Iceland that include the word jökull or jökla, which means glacier. This inquiry is less of a statement on colonialism and more to get a sense of how intrinsic the notion of the glacier has become within Icelandic over the past thousand years since settlement. With the predicted extinction of Icelandic glaciers over the next two hundred years, how might words including jökull or jökla act as archives of future loss?

Short periods of time spent in Norway have proven generative for engaging Norwegian as literary material for my lack of fluency. I started a poetry collection called Nord in 2013 during a festival in Lofoten. Amidst much dark and blizzard, I staged language acquisition of words like ord (word), lys (light), and lyd (sound) as visual poems in the darkened snowscape. During a 2017 literary workshop that was part of the Greenlight District Eco-Arts Festival in Skien, I wrote a poetic series called Blåskjell i Biocide that threaded overheard fragments of Norwegian and Swedish texts written at the workshop by Gunstein Bakke, Malmfrid H. Hallum, Cecilia Hultman, Mette Karlsvik, Hanne Ramsdal, and Aina Villanger.

I have also been gathering the word sund within place names in Nordic countries for Jon Ståle Ritland and Michiel Koelink’s 3D Poetry Editor. I gathered those words to try and get a sense of how prevalent those geographic components are for Nordic countries—sund being a body of water larger than a bay or bight. Ocean bodies. The comparable word in English is sound.

Not entirely, but as you can see in my examples, I’ve relied on much repetition of ecosystem components as a way to get the lay of the linguistic and geographic land. Repetition as a core element of language acquisition, and repetition as a way to defamiliarize and estrangement.

EuropeNow You have been talking about the gathering of words, which makes me think of Ursula le Guin’s fantastic essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction sketching narrative spaces as means to carry and to care for alternate stories to the prevalent notion of “man the killer.”

Visual poem excerpted from Nord by Angela Rawlings. Credit: Angela Rawlings, 2013.

Angela Rawlings This feels like an extended conversation that we have been having for years under the umbrella of Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, and it is a privilege to be able to perform in the public space of this interview the kinds of conversations that we engage privately. To have a practice as we do through the Laboratory—as collaborators and as people in an editor-author relationship—implies our practice of caretaking. In an interview, we perform our caretaking publicly, to show and to share, to say: “This is a way we have devised to discuss these issues of interconnection and eco-action.”

When you say caretaking, I immediately think of indigenous practices of stewardship—caretaking the earth as kin. How do we nurture those that nurture us? It is understandable how an immense thinker like Donna Haraway would relate to these indigenous practices and sources of deep knowledge with her urging to make kin as a plausible way forward, as a possible way to stay with the trouble. Thinking about Haraway’s assertion that “[i]t matters what stories tell stories (Haraway 2016),” for me, it also matters what care carries care.

EuropeNow But how can we care as knowledge-making bodies? How can knowledge extend into practices of caring?

Angela Rawlings With whom and how we spend our time feeds, nourishes, and/or depletes who and how we are. And when I say who, that links back to the question of who a who can be. A mountain body, a body of weather, fishbodies, fruiting bodies of shiitake, the minute bodies of cancering cells….

If I spend my time proximal to jökull, cancer, sund, or by the industry park in Herøya, Norway where blue mussels (Mytilus edulis) have high toxicity levels from exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants, it matters with who and where I am attending, and how I frame or phrase the experiences I carry with me from our interactions. I become a carrier bag of interconnections, interactions, experiences, and relationships with which I’ve come into contact willingly or not. It matters where we focus our attentions and our tensions. And it matters how we formulate these relationship through narratives we tell ourselves about these experiences we carry. These narratives change us and change within us, and the ways in which we construct languages into narratives inscribes the quality of the care and the carrying.

EuropeNow Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the etymological connections between curating and cure. In order to take on questions of the reparative potentials of aesthetics, it seems to me that we need to foster acute attention to matters of exposure and vulnerability within our practices, which is exactly what I find so inspiring in your work.

Angela Rawlings I am thinking about fiction and authenticity—imagining language as a sort of fictive gauze, very thin and protecting experience within fictions. We frame experience in shorthand narratives because it is impossible to relate and represent an experience within the same parameters in which it originally occurred. That shorthand fictionalizes the fullness of an authentic lived experience. I grapple with my compulsion for authenticity, towards a real connection, a material being-with, whether it is a being with self or with other bodies.

My compulsion superimposes an authentic, as yet unfictionalized present with a narrativized, recollected past. How do my narratives expose vulnerabilities—coping mechanisms, desires, fears? To make oneself open to discuss and expose embodied experience is vulnerablizing.

Think about a question we ask each other all the time: how are you? There is a script of how we respond to this, usually stating we are fine even when we are not fine. Vulnerability flares in the potential of exposure of a past discrepancy, or a future unscripted. How beautiful our vulnerability exposed when we defamiliarize ourselves from rote, everyday scripts such as how are you / fine and answer afresh with the authenticity of that moment.

EuropeNow Most of us tend to “save” such vulnerable conversations for later, pushing them to the margins of our professional lives as something rather compromising, “unserious,” embarrassing even. My colleague Dea Antonsen and I had a defining moment while guiding an audience though our newly opened exhibition. We paused before American artist Kathy High’s Rat Love Manifesto, a deeply touching plea towards learning to care for unloved others in the shape of laboratory rats. Presenting this work, we could not hold it together, and soon we were crying in front of our audience, which was a very uncomfortable experience, but also a deeply transgressive and generative one. After all, we have been arguing against normative ideals of objectivity in knowledges, so a few curator’s tears actually seemed pretty appropriate. From then on, affect has become a beacon in our work, not just as ‘theme’, but as working ethos. The question, I think, is: How do we accommodate and work with such moments of intimacy and exposure in professional situations?

Angela Rawlings I get my kicks out of subverting rules. If someone says write a poem about a tree, I am not going to write about a tree, I am going to see how I can subvert that instruction, in a way that can fulfil the instruction and at the same time expose the instruction as being an instruction. In some senses my methodology embraces disruption. And rupture. Defamiliarization. Estrangement.

I have often had the feeling that I am not “doing academia” correctly. When is the right moment, if there ever is, to disclose a personal experience in a semi-public or public academic (or artistic, or social) discussion? There are conventional, prescribed expectations for how we govern ourselves within academic events. To disclose cancer experience or rape or death in the family—to have trauma enter a conversation, not as a disclosure for personal reasons but that is adding to the material conversation of the academic concerns of the conversation—how do these disclosures disrupt the emotional distances we have been trained to engage in these contexts?

How do we signal our humanity to one another as we continue to raise our numbers on this planet? How to respond to how are you? How can we engage our spaces so we are genuinely present with each other? One of my big struggles is how to do this in a way that is not depleting personal resources like energy or time. If I am not protecting my energy stores I have in play, how is my body rendered less of a functional carrier bag because I am not figuring out great strategies for self-care? How are we not draining our energies when there is such a big need for care all around and within us?

EuropeNow This is getting very somber, should we talk a little about the animated or desiring body. Or the desiring for the magic and joy of interconnection?

Angela Rawlings I am thinking about late twentieth century environmental movement shame tactics on how to not litter, how to reduce water consumption, etc. The question has become: How else can we approach dissemination of the many strategies that support healthier co-habitation within our ecosystems? Is there a way to communicate the necessity for this kind of care in a planetary context that has come as a result of our North/Western human-producing activities? Is there another way that we can communicate to ourselves that is not bringing about the negative feeling of shame, but something more positive in its scope in thinking about how to be better planetary citizens to our more-than-human and human kin? How do we not go to bed feeling the weight of the world on our shoulders, even when we should?

EuropeNow Maybe this is where magic could enter the communication, as in generative and intra-active potentials of joyous relationships?

Angela Rawlings Absolutely. So many clever generations of humans in the past have created systems of knowledge handed down with care through indigenous communities. Mantic arts have often devised ways to tune into or to relate to ecosystem components through the guise of speculating on futures or considering strategies for how to deal with a situation in the here and now. Someone throws sheep bone like dice and then juxtaposes the bones’ spatial, visual, and textual relationships with a situation about which the caster desires greater insight. Someone else learns how to gather herbs at propitious moments in the year of benefit to herb (for its abundant growth or repopulation) and human (as curative, as nourishment). It is exciting to see ritual-making and magic practices blossom within popular culture the last few years, which will hopefully lead to folks figuring out an environmental stewardship that has as its core the wide-eyed joy and astonishment that comes through a longer-term awareness of how one dwells in co-existence with ecosystems/bodies.

EuropeNow Speaking of ritual-making and magic, can you tell me a little bit about your recent work Intime?

Intime performance with Rebecca Bruton in Kinghorn, Scotland. Credit: Angela Rawlings, 2017.

Angela Rawlings The work plays with the words intime (French for intimate) and the English-language in time. Duration and intimacy. The idea grew from an attempted embodiment of counter-clockwise North Atlantic surface-wind currents. This conjures other spiralities for embodied relations, such as the whorl of periwinkle shell (a sea snail) or cochlea (spiral of our inner ear), the spiralic shape of galaxies, etc. Intime is an attempt to research how to perform geochronology in the Anthropocene, exploring sites impacted by geochronologic markers such as climate change or mass extinction, exploring multiple temporalities hidden and apparent within the landscapes we engage.

In Intime, I invite people to visit an ocean’s foreshore at low tide to walk in counter-clockwise circles as a way of coming into direct contact with more-than-human bodies in a location of shifting access. A foreshore is a liminal space, a space changing with the tide, redrawing borders of land and ocean. Who dwells there? Who visits there? With Intime, I am performing with other people as a way to establish camaraderie through a sense of collected ritual, enjoying and exploring the unusual moment and movement we have gifted ourselves. We explore becoming-with the many other bodies, human and more-than, populating the site.

What can happen in this moment of interaction? How might a participant become a carrier of foreshore intimacy, how does that person carry the experience within her body, and how does she relate it or to it in the future? Might she walk in circles elsewhere…? What does she remember of that place where she performed the walk, and what that place taught her?

EuropeNow How do you categorize this work?

Video still from How to Have a Conversation with a Landscape. Credit: Angela Rawlings, Andra Roman, and Marzena Krzemińska.

Angela Rawlings To produce this as artistic practice as research, the frame of the work is academic. I came up with the idea while pursuing a PhD at University of Glasgow, where I am writing contextually about the work. That said, it is a creative work both as academic research but also separate from it. It’s its own entity; it is an interconnected body. Intime is a performance art practice. It’s also ritual or lifestyle practice; it doesn’t need to be labelled within an arts context, though I do think of it as performing geopoetics. So even though I am not thinking so much of the poetry of the gesture, I do recognize components of Intime that engage language as material, since we are inscribing a large letter O on the foreshore when we walk in circles. I am aware that in Scandinavian languages, the word for island is Ø or Ö. We are inscribing half of the word island in the foreshore and walking with the full knowledge that that word will be erased by the ocean. I cast this as a geopoetics, a large almost one-word poem written by a group of people and then edited by the ocean. We should have more oceanic editors.

Angela Rawlings is a Canadian-Icelandic poet and an artist approaching questions of ecopoet(h)ics and relational empathy between unalike bodies from multidisciplinary, multisensorial and multilingual vantages. Rawlings’ practice spans sensorial poetries, vocal and contact improvisation, theatre of the rural, and conversations with landscapes. Her books include Wide slumber for lepidopterists (Coach House Books, 2006), o w n (CUE BOOKS, 2015), and si tu (MaMa, 2017). Her libretti include Bodiless (for Gabrielle Herbst, 2014) and Longitude (for Davíð Brynjar Franzson, 2014). Rawlings is a PhD candidate at the University of Glasgow researching performative geochronology in the Anthropocene. Rawlings dwells, lives and loves in Iceland.

Ida Bencke is an editor with Broken Dimanche Press, and co-founder of Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, a curatorial platform for planetary becoming. She is based in Berlin.

Published on April 17, 2018.