Translated from the Icelandic by Larissa Kyzer.

This is part of our special feature, New Nordic Voices.

My hands get no cleaner than an old bathtub. My fingernails are all clipped as short as possible, but the chemicals have managed to claw their way through the dead skin, into the bone. As if there’s no enamel.

When I say bone, I mean the nails, because nails are a kind of bone. Or rather, ‘horn’ would maybe be a better word, but at any rate, it’s as if some chemicals have blended with the proteins that nails are woven from. When I say dead skin, I just mean the outermost layer of the skin. It’s just dead cells.

Then under them, there’s the dermis, and under the dermis is the hypodermis.

Life.

My hands look dirty. But in reality, they’re clean. They’re cracked from handwashing and the cold. Coarse from use. Large and thick because that’s how hands are in my family. Likewise, the legs in my family are short. So that we don’t have to bend too far down to the dirt and our toes are squat. Our soles are flat under the weight of the temperaments that we carry on these short legs. In these large, outstretched hands.

My name is Elín Jónsdóttir. Daughter of Guðrún and Jón. Birth year, 1946. Birthday, the ninth of January. They’re deceased, Guðrún and Jón. Have been for some time. I’m mother to no one.

I make props, but I’m no novelist. Though there’s probably some similarities between these two things, there are, nevertheless, many more differences. In order to write this, I had to sit still and use my hands in such a way that my back became riddled with pain.

I don’t know how to touch-type and use only the index finger on my left hand and the middle and ring fingers on my right. I alternate staring down at the keyboard and up at the screen and there’s something that happens. My mind steps away from the material, leaves the pain behind, teeters on the roof.

The reason I decided to write this is that if I don’t, no one will, which is a predictable outcome. The story’s injustice is, nevertheless, a matter of no importance; there’s injustice there because there’s injustice everywhere. Intrinsic to our stories because it’s intrinsic to us.

When I say us, I feel as though I’m lying. Maybe if I say it more often. Over and over again.

Then would I start to believe that it’s true?

US

I’ll say it just to absolve myself of responsibility—I’m talking about myself, but I’m trying to drag you all through the mud with me. The injustice is here, within me, that’s why I’m dealing it, not with you.

YOU.

My respect for YOU has been shattered countless times, disintegrated many times over, and disappears and reappears and is smashed into pieces. Every diagnosis contains a hundred, and all of them are wrong. All of them are right. Nothing you do is wrong. Everything you do is terrifying.

And there’s a good reason that no one would write this story: because there is no story. Just an attempt to connect signs that were conveyed in waking life and in dreams. Don’t worry—I’m not going to lull you all to sleep with dreams, but the signs make it clear to me that the mind is not a thing, that it’s not something you can touch.

The same is true for all things, and that’s what this story is about.

But not about a girl.

Whose name is Ellen.

I met her the day after the boxes were found. Which is so typical of this whole story that it all flows together in my mind. Ellen flows up into and down out of the boxes—lost, found, stolen, cardboard boxes.

Not long before, whiteflies had shown up, yet again. I’d tried all sorts of things before—vinegar, dishwashing liquid. All that stuff. Separated the plants, sprayed them, dried them out. The flies always came back until at last, I gave up and threw them all out.

It was rough. All of the plants came from people who I cared about, most of whom were dead. I’m not saying, mind you, that I was devastated, or that I’d cried. But it was very trying all the same.

A week later, an event occurred that I also associate with Ellen Álfsdóttir and the three boxes.

I was messing around with the cords behind the television—an old tube TV that was connected to an antenna, the old-fashioned way—when I closed my hand around a living thing. In a matter of speaking, cords are, of course, living things. Or anyway, the electricity that travels through them isn’t dead, but the thing I was touching was different. It was organic. I was stooped over in a dark corner and felt its vital signs and tugged.

It was a plant. Not one of the plants I’d thrown out. It was unlike any plant I’d seen before, in the sense that it had no roots, no bottom. A perfectly self-sustaining tangle that drew breath. Like some David Attenborough program had taken a shit behind the television. I took a picture of it on my phone and did an image search. Tillandsia, said the Internet. A plant from Central and South America. A rootless plant that lives on air. Bright green leaves, long and delicate, that grew in a strangely symmetrical fashion, as if each leaf was trying to envelop the next. Like some kind of orgy, and I peered into it, searching for something that might be the beginning or the middle, but I found nothing.

Some types grow flowers, I read, and indeed, I saw signs of this on my plant. There was a minuscule pink bud in one spot.

Logical readers might imagine that some friend of mine must have wanted to have a bit of fun and surprise me with this fanciful gift, which gives me the chance to sneak in some important info, namely:

I don’t have any friends. Not a single one.

No one’s crazy. I mean what I say. Reality has so many sides to it that best case scenario is that it’s cubistic. Worst case scenario, it’s predictable. Never flat

A week later, the real estate agent called and told me that they’d found a cold little storage room in my grandma’s old house that wasn’t on any of the blueprints and that in it, there were three boxes with my name on them.

It was odd. I had never considered what had become of my things from my childhood and teenage years. It was like I assumed that they’d just vanished of their own volition. Some things I’d thrown out, other things were lost. The rest had maybe gotten mixed in with someone else’s collection of stuff, or had left home, like me.

But there were three boxes, said the real estate agent. Boxes that someone had to have sorted out.

Elín, Papers.

Elín, Books.

Elín, Misc.

All the worldly belongings that I’d left behind in my bedroom all those years ago.

In addition to those three boxes, there were a few boxes of books in the storage room, a pile of tablecloths and embroidery, broken audio equipment, dust, mouse droppings, and spider webs.

I’ve tried to avoid everything that concerns that apartment—just engaged a property manager and paid the bills—and now it was empty, spotlessly white with a gleaming floor and pictures of it had been included in the newspaper’s real estate pages. Everything was ready when this storage unit in the basement had come to light.

I don’t even have a broom, I apologized after we’d stacked the boxes in the backseat of my car. The real estate agent waved that away, said she’d take care of it. She was on edge. As if she were selling her first property or wasn’t a real estate agent at all. Young and fast-talking, like she was performing the idea of a man.

Thank you, I said, leaving her with the spider webs and mouse droppings. I asked her to take the embroidery to the local charity shop and I knew very well that I was belittling her, but that was okay, wasn’t it?

I found it kind of enjoyable.

We all have our quirks.

On my way home, darkness came crashing down on the city. I listened to the news on the radio. The police were seeking information on the whereabouts of a pale man, wearing a parka and gloves. It was the beginning of February and I wondered who wasn’t pale and wearing a parka and gloves right now.

At home, Ellen’s script was waiting for me, unread. The script of the play that would be staged in the fall. Rumor had it that it was completely ready, that its construction was perfect and that if the director tried to change so much as a comma, the whole thing would go to pieces. The vivid characterization was truly unprecedented and the style exceptional.

I flipped right to the character descriptions and squinted at the page:

THE FATHER:

A pile of bandages, some of them sodden. But nothing is wrong.

It had been a long time since I’d gone near a theater. When I was younger, I sometimes worked in the prop department for short periods of time, but for the last thirty years, I’d really only worked in film and television.

Hreiðar, the director who was going to stage the young genius’s play, had primarily made movies, even though, like me, he’d gotten his start in the theater. I’d worked with him often. Now he was middle-aged and had been known as the Next Big Thing for going on twenty years. Which is to say that the theater had the idea to bring him in for this play and he was probably desperate. Wanted to have a hit—a sheep in formaldehyde—something that freed him of people’s expectations and guaranteed him some security.

Oh, to live in security!

When he called and asked if I had time, my first reaction was to say no. Mainly because I’d become so consumed with close-ups, minutia, perfection. With materials that were like skin. With nuances. With this kind of hyper-delicacy. The kind of concentration that this precision demanded was addictive. In the theater, everyone could care less about that. Movements needed to be large enough that the people in the very back could see them, and likewise, the costumes. The props badly painted Styrofoam and particle board, if I was remembering correctly.

Just read the script, said Hreiðar. You’re going to love the descriptions. It’s perfect for a modernist like you—we’ve just got to have you on the team. You’re gonna to love it.

I promise, he said, and I was going to say goodbye when he happened to drop the young genius’s name.

Ellen Álfsdóttir, he said.

Álfur Finnsson’s daughter? I asked.

Yes, that’s right, he said. Quite a selling point. We’ve got a huge stage, plenty of money—that’s why I’m calling you. Haha.

Is the first read-through this coming Monday? I asked and Hreiðar fell silent.

Are you going to join us? he asked, clearly unprepared for my agreement.

The first reading’s on Monday, he hurried to say then. Naturally, you don’t have to come to the rehearsal unless you want to…but of course you’re very welcome.

Send me the play, I asked, and in almost the same moment, received a notification saying that I had a new email. I printed the script out right away, but since then, it had wandered, unread, between the kitchen table and the living room couch.

I was overcome with the fatigue particular to the short days of winter and got to my feet, went into the living room. Everything was a mess. My work room was constantly eating up square footage in the house. There was a thick plastic sheet on the dining table and a great deal of clay under it. Curving up out of the clay in the middle and out from under the plastic was a horn that I was shaping. The horn was supposed to look like a rhinoceros horn that played a big part in a movie that was to be shot over the summer, but the director didn’t want to use a real horn for political reasons.

The world hungered for young geniuses. I’d watched a few of them meet with success and then disappear altogether or else fell in line with other unexciting professional bards. Generally, it wasn’t their genius that captivated people, but rather just their freshness and youth. Their skin, rather than their talent. The hope for something new draped like an invisible cloak over the stale old lore that men had gone on reciting, over and over and over.

Ellen’s father, Álfur Finnsson, had also been The Next Big Thing in his time, and later, a distinguished author. He died many years ago. He was a playwright, among other things, and I’d actually worked on a few of his productions. Gotten to know him a little.

Back around 1980, I built a mountain out of sod that was blown up at every performance as soon as the curtain was raised, night after night. The duration of his life was as tragic and dramatic as his plays. Not least the end of it, but Ellen was not but maybe two years old then.

My interest in her own play undoubtedly stemmed from this as well. A lot had been written about Álfur Finnsson and his work, but very little was actually known about his final years. About the young woman with whom he had a daughter, Ellen.

He was ten years older than me and I remember well the hubbub that was generated by his first book. Later, when I’d started to work a little at the theater and we met, I was rather intrigued by him. Not in such a way that I wanted to get to know him well, though, and I never admired him. But it isn’t often that you meet people who can so easily sweep their environment along with them and fill it with salacious stories.

I followed the gossip about him, listened from a distance. It was like every other soap opera, of course, and how was that any of my business?

Until I accidentally got mixed up in the most salacious story of them all.

I found my reading glasses next to the TV remote and then went back into the kitchen and sat down to read again, but I couldn’t manage to stay focused. When I’d looked up rhinos online a few days earlier, countless close-ups of wounds had come up and ever since, I hadn’t been able to stop thinking about the process of ripping a rhino’s horn off.

Then the horns were sold on the black market.

No, I had to finish the horn. Then I could read the young girl’s masterpiece while it dried. I wrapped my work shirt around me and turned on the radio, sat down at the dining table, and carved very fine lines into the clay with a bristly wire brush.

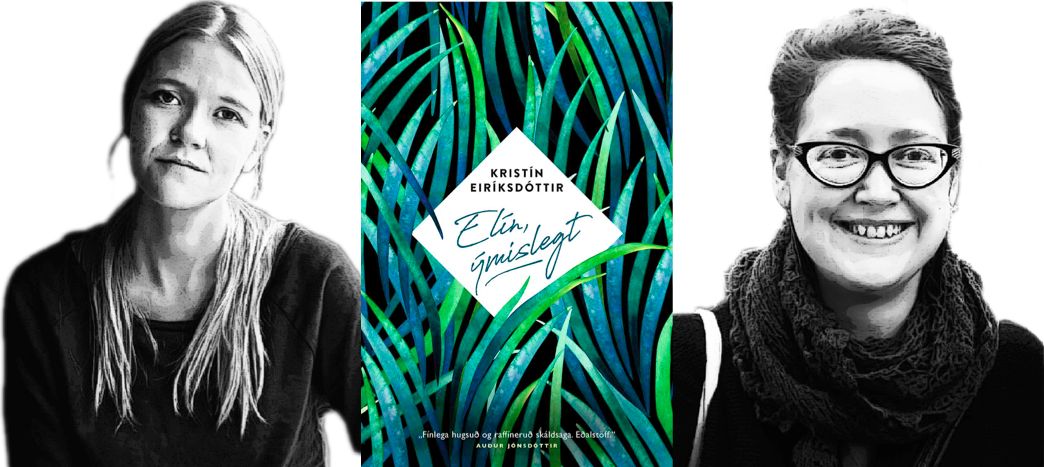

Born in Reykjavík in 1981, Kristín Eiríksdóttir is the author of three works of fiction, five poetry collections, and three plays, as well as numerous other articles and artistic works. Her first book, Meat Town (2004), straddles the divide between poetry and narrative and was hailed upon its release for its idiosyncratic sense of humor and powerful imagery. Since then, Kristín’s work has consistently earned her both critical and popular acclaim, including a nomination for the prestigious Icelandic Women’s Literature Prize for her first novel, White Fur (2012). Misc. is her most celebrated work to date, winning the Icelandic Literary Prize and the Icelandic Women’s Literature prize, coming in second for the Icelandic Bookseller’s Prize, and being recognized as one of the best books of 2017 by the Icelandic National Broadcasting Service.

Larissa Kyzer is a writer and translator who was awarded a 2012 Fulbright grant to Iceland, where she lived for five years. Her translations include a collection of horror stories written by six to eight-year-old Icelandic schoolchildren, as well as fiction and poetry by Andri Snær Magnason, Auður Jónsdóttir, Ingvi Þór Kormáksson, Kári Tulinius, Kristín Ragna Gunnarsdóttir, Kristín Svava Tómasdóttir, and Steinunn G. Helgadóttir. Her translations have appeared in CV2, Gutter, Ós — The Journal, Words and Worlds, Lunch Ticket, and Exchanges and are forthcoming in Quiddity. Larissa earned her Master’s degree in Translation Studies from the University of Iceland in 2017 and now lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Published on April 17, 2018.