Translated from the French by Miranda Richmond Mouillot.

This is part of our special feature on The Crisis of European Integration.

One night, I dreamed that I was standing on the roof and that Madame Julie was standing below, on the sidewalk, her eyes raised to me, waiting for me to jump so she could catch me in her arms. Ultimately, the moment came when, seated across from her in the kitchen, I hid my face behind my hands and broke down sobbing. Then she listened to me until two in the morning amidst the noise of the bidets, which didn’t really ever stop in the Hôtel du Passage.

“Who is that stupid?” she murmured, when I informed her of my intent to make it back to Poland at all costs. “I don’t understand why they didn’t take you in the army, fool that you are.”

“I was exempted. My heart beats too fast.”

“Listen to me, kid. I’m sixty years old, but sometimes I feel like I’ve lived – survived, if you’d rather – for five thousand years, and even like I was there before, at the beginning of the world. Don’t forget my name, either. Espinoza.” She laughed. “Almost like Spinoza, the philos- opher, maybe you’ve heard of him. I could even drop the ‘E’ and call myself Spinoza, that’s how much I know…”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“Because pretty soon things are going to get so bad, it’s going to be such a catastrophe, that you and your little big booboo there are going to disappear in it. We’re going to lose the war and we’ll have the Germans in France.”

I set down my lass. “France can’t lose the war. It’s impossible.”

She half-closed one eye, over her cigarette, “Impossible isn’t French,” she said.

Madame Julie stood, the Pekinese in her arms, and went to pick up her bag from a bottle-green plush arm- chair. She drew out a roll of banknotes and returned to the table.

“Take this, for a start. There’ll be more later.” I looked at the money on the table.

“Well, what are you waiting for?”

“Listen, Madame Julie, there’s enough to live on for a year there, and I’m not too keen on living.”

She chuckled. “Awww, it wants to die of love,” she said. “Well, you’d better get cracking. Because people are going to start dying like flies, and it won’t be from love, let me tell you.”

I felt a rush of sympathy for this woman. Perhaps I was starting to sense that when people speak disdainfully of “whores” and “madams,” they are locating human dignity in the ass, to make it easier to forget how low our heads can sink.

“I still don’t understand why you’re giving me this money.”

She was seated in front of me, with her mauve woolen shawl drawn across her flat chest, with her dome of black hair, her bohemian eyes and her long fingers playing with the little golden lizard pinned to her bodice.

“You don’t understand, of course. So I’ll explain it to you. I need a guy like you. I’m putting myself together a little team.”

And so it was that in February 1940, while the English were singing “We’re Going To Hang Out The Washing on the Siegfried Line,” the posters were proclaiming that “We Will Win Because We Are Strongest,” and the Clos Joli was resounding with victory toasts, one old madam was getting ready for the German Occupation. I do not think that anyone else in the country had at that time thought to organize what would later be called “a resistance network.” I was charged with making contact with a certain number of people, including a forger who, after a twenty-year sentence, was still nostalgic for his profession, and Madame Julie convinced me so thoroughly to keep this a secret that even today I barely dare write their names. There was Monsieur Dampierre, who lived alone with a canary – and here it must be said in favor of the Gestapo that they spared the canary and took it in when Monsieur Dampierre died of a heart attack under questioning in 1942. There was Monsieur Pageot, who would later be known as Valérian, two years before his execution by firing squad with twenty others on a hill that bore the same name; and Police Commissioner Rotard, who became the head of the Alliance network and who spoke of Madame Julie Espinoza in his book, The Underground Years: “A woman in whom there was a total absence of illusion, born no doubt of the long exercise of her profession. Sometimes I imagined dishonor coming to visit the woman who knew it so well, and confiding in her. It must have murmured in her ear, ‘My hour is coming soon, my good Julie. Get ready.’ At any rate, she was very convincing, and I helped her to organize a group that met regularly to envision various measures to be taken, from forged paperwork to the choice of safe houses where we could meet or hide out during the German occupation, which she did not doubt for a single instant would occur.’” One day, after a visit to a pharmacist in the Rue Gobin who gave me some “medicine” whose nature and recipient I would learn only much later, I asked Madame Espinoza,

“Do you pay for them?”

“No, my little Ludo. Some things can’t be bought.” She shot a strange look in my direction, a mixture of sadness and harshness. “They’re for the firing squad.”

One day I also wanted to know why she didn’t flee to Switzerland or Portugal, if she was so sure that the war was lost and considered the arrival of the Germans as a certainty.

“We already talked about that. I told you: I’m not the fleeing kind.” She laughed. “Maybe that’s what old Ful- billac meant when she kept saying I wasn’t “the right sort of person.” One morning, I noticed some photographs in the corner of her kitchen, one of Salazar, the Portuguese dictator; one of Admiral Horthy, regent of Hungary; and even one of Hitler. “I’m waiting for someone to come autograph them for me,” she explained.

Madame Julie never did trust me enough to tell me the new name she intended to adopt, and when the “specialist” arrived to sign the portraits I was enjoined to leave the room.

She made me get a driver’s license. “It could be useful.”

The only thing the boss was unable to predict was the date of the German offensive and the defeat that would follow. She was expecting something “as soon as the weather turns nice,” and was worried about what her girls would come to. There were thirty or forty of them, working in shifts around the clock at the Hôtel du Passage. She advised them to take German lessons but there wasn’t a whore in France who believed we would lose the war.

I was surprised at her confidence in me. Why such unhesitating trust in a boy of twenty, in someone of whom life could still expect anything – which was not necessarily an endorsement?

“I might be making a mistake,” she acknowledged.

“But you want me to tell you? You’ve got that firing squad look in your eyes.”

“Shit,” I said.

She laughed.

“Scared you, eh? But that doesn’t necessarily mean twelve bullets to the head. You can live to a ripe old age with it. It’s your Polish girl. She gives you that look. Don’t worry. You’ll see her again.”

“How can you know, Madame Julie?”

She hesitated, as if she didn’t want to hurt me. “It would be too beautiful, if you didn’t see her again. It would stay whole. Things rarely stay whole in this life.”

Two or three times a week, I continued to show up at the French headquarters of the Polish Army, and finally, a sergeant, sick of my questions, called out to me, “We don’t know anything for sure but it’s more than likely that the whole Bronicki family died in the bombing.” But I was certain that Lila was alive. I even felt her presence grow- ing by my side, like a premonition.

At the beginning of April, Madame Julie disappeared for a few days. She returned with a bandage on her face. When the compress was removed, Julie Espinoza’s nose had lost its slightly hunchback look and had become straight, shorter, even. I didn’t ask her any questions, but seeing my astonishment, she told me, “The first thing those bastards will look at is noses.”

I ended up with such complete trust in her judgment that when the Germans broke through at Sedan, I wasn’t surprised. Nor was I surprised, when, a few days later, she sent me to get her Citroën from the garage. Returning and entering her room, I found her sitting among her suitcases with Chong, a glass of eau-de-vie in her hand, listening to the news on the radio, which was announcing that “nothing has been lost.”

“Some nothing,” she observed.

She set down the glass, picked up the dog, and rose to her feet.

“Right, we’ll go now.”

“Where?”

“We’ll go a little ways, together, because you’re going home, to Normandy, which is in the same general direction.”

It was June 2, and there was no trace of defeat on the roads. In the villages we drove through, everything was peaceful. Madame Espinoza let me drive, then took the wheel herself. She was wearing a gray coat with a mauve hat and scarf.

“Where are you going to hide, Madame Julie?”

“I’m not going to hide at all, my friend. The ones who hide are always the ones they find. I’ve had smallpox twice; the Nazis just make it a third time.”

“But what are you going to do?”

She smiled a little and said nothing. A few kilometers from Vervaux, she stopped the car.

“Here we are. We’ll say goodbye. You’ll make it home from here, it’s not too far.”

She gave me a kiss. “I’ll be in touch. We’ll be soon needing little guys like you.”

She touched my cheek. “Go on, now.”

“You’re not going to tell me I’ve got that firing squad look, again, are you?”

“Let’s just say you’ve got what it takes. When a guy knows how to love like you do – to love a woman who’s not there anymore, then chances are you know how to love other things, too… things that won’t be there any- more either, when the Nazis start in on them.”

I was outside, holding my old suitcase. I felt sad. “At least tell me where you’re going!”

She started the car. Standing in the middle of the road, I wondered what would become of her. I was also a little disappointed in her lack of trust, in the end. Apparently, whatever she had read in my eyes wasn’t sufficient guarantee. Oh well. Maybe it was for the best. Maybe I didn’t have that firing squad look after all. I still had a chance.

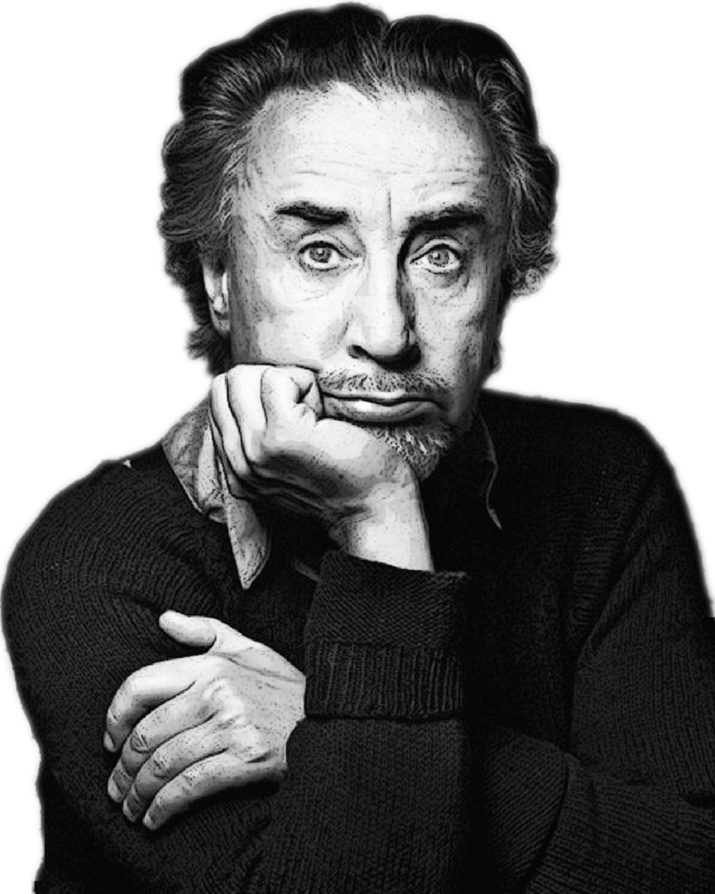

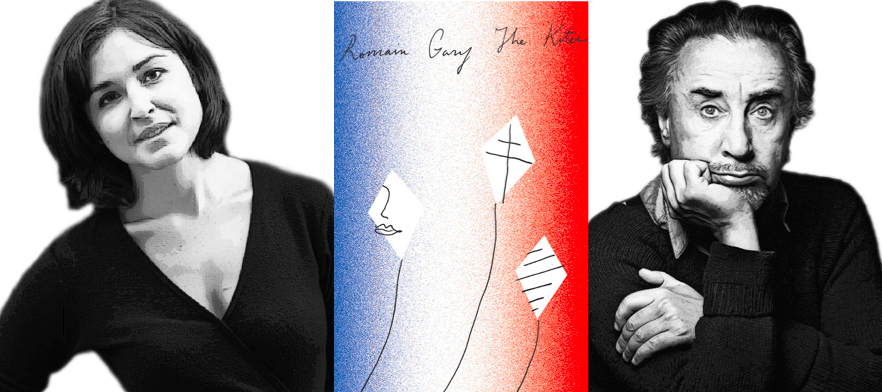

Romain Gary (1914–1980) was born Roman Kacew in Vilnius to a family of Lithuanian Jews. He changed his name when he fled Nazi-occupied France to fight for the British as an RAF pilot. He wrote under several pen names and is the only writer to have received the Prix Goncourt twice. A diplomat and filmmaker, Gary was married to the American actress Jean Seberg. He died in Paris in 1980 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Miranda Richmond Mouillot is a writer and translator and the author of A Fifty-Year Silence: Love, War, and a Ruined House in France. She won a PEN/Heim Translation Award for her translation of Romain Gary’s The Kites.

This excerpt from The Kites is published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 1980 by Éditions Gallimard. Translation copyright © 2017 by Miranda Richmond Mouillot.

Published on November 2, 2017.