Translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith.

This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

It began in Mao’s room. Hazy, formless, faint things, things that were neither light nor shade, yet at the same time the illegitimate children of both, a moment of glittering black and dark whiteness, confusion that swept down the backbone, and then a sudden voice. Do not tell anyone about this. This feeling, these non-sensations of leaden abstraction. But since the familiar, mistaken attempts at talking about what cannot be said were gathered together into a single face, a montage of confusion, people said that the face that appeared in photographs was mine.

“No, that’s not me, you saw me wrong, you or your camera.”

“Even if that were the case, what’s certain is that this is you at the moment the camera went off, even if it isn’t you as you are now.”

But photographs are taken of countless faces, uncountably many, in the literal meaning of the phrase; there has to be some clear reason to be able to distinguish—not indicate—this one face from among them, this face made up of several large white holes, an unspecific black background, and densely clustered windows of indefinite form, as me. Mao is a photographer, which means that taking photographs is one of the various things he does to make a living.

We live as photographs. I imagine, we live as a performance without a stage. Or else as writing, as theater, as a writer of pamphlets, a publisher of books, a traffic-light repairer; a translator of trade documents, white goods’ manuals, and medical prescriptions; a speaker at exhibition openings, a business-card designer, a magazine contributor, a maid, a writer of travel essays and critic of miscellaneous things, all possible types of freelancer, a guest lecturer at an art institute, the debtor of a bank, one unemployed by grace, thanks to all unpredictable temporary things whose forms are very different to what we had expected. I imagine. In order to further extend the life of my imagination, which is made up of everything it is possible to imagine, I want to imagine still more, to arrive eventually at the skin of what cannot be imagined, to feel it. Mao specialized in photographing certain specific parts of the human body; the money he was able to make through this unique line of business was thanks to the various women who were always completely happy to model for him without receiving a single penny in return.

I can’t take this photograph home, I imagined. And I especially can’t mail it to them. If I did, they would all get angry, both people I know and people I don’t. They would think that I’d deliberately intended to anger them by sending them such an imprecise photograph. But Mao can get just as angry, too, so I try imagining that. In certain cases, Mao will get angry at me arbitrarily. But I don’t get angry. Unless, unrelated to this photograph, a pathetic dog in a jester’s costume chases after me. There’s no need to go far back in time for a specific instance; it happened only yesterday. I was going about my business when someone threw a good-sized fruit at my shoulder. It was a furry brown fruit from the fruit market. When I turned around in surprise, one single laugh burst out, high and exaggeratedly loud, shrill and antagonizing, from between the other laughter that was rowdy, or rather, to be exact, rowdy yet timid. Its author was a performer, in a manner of speaking, the emperor of amusement and instigator of humor; making people laugh—making them burst out into great guffaws—was his job. This is how he made his living. All the people at the roadside cafe laughed as they stared at me. With a look in their eyes that demanded that I understand the joke as they did. But the anger was welling up inside me, and I flared up like an old woman brandishing a cane. I knew the joker. I’d fallen victim to his surprise attacks a couple of times already, always a similar trick. One time, I was crossing the square in the middle of the day when he snuck from behind and grabbed my hand. I kept on walking, not thinking much of it as I simply assumed that the owner of the hand must be Mao. Because of course, it didn’t occur to me turn to look and check. That time, too, it was the sound that flustered me, that impetuous, persistent, clearly malicious sound, shrill as a scream—his laughter. Only after the sound had shaken me did I become aware of the unfamiliar hand that had stealthily crept into my palm. A huge throng of tourists, gathered on the terrace of the cafe in the square’s center, warm in the sun, laughed merrily as they watched us, the joker and I. Oh, that’s right, tourists. An old crowd, their mood marred by fitful sleep and the hotel’s tasteless food, and worn out from spending the entire day being bussed around city center sights, which were basically the same, and who had been winding down with mugs of beer in front of them, their eyes gleaming, craving some light entertainment. Entertainment of the type that, despite its lightness, would be suitable for them, tourists at a tourist destination. Humor is humor, after all, the joker said right into my ear, as I took in the big red Pierrot nose protruding from powder caked on so thick it resembled a mask. His eyes, so transparent that you almost couldn’t tell what color they were, stared hard at me from frighteningly close up. Dear god let me not have to experience this kind of humor twice in one lifetime. There’s nothing wrong with playing the fool. It’s not as though the idea of being made a laughing stock, helpless in a foreign land, is completely unbearable to me. But that laughter! An eardrum-shattering octave, massively exaggerated! A frantic cawing produced by the bloodied beak of an enormous bird flying hundreds of kilometers, its great wings covering the whole of the sky! The worst aria, in which the very highest notes, which ravage the singer’s vocal chords, rise above each other and are forever connected, a comedy of insults mixed with ridicule in which the intention to make something inside the human body spontaneously combust through repetitive stimulation is all too clearly revealed! The insane merriment of the most cruel and excessive human beings! That acoustic assault is what’s unbearable. I glared at the joker but, in the end, was unable to let myself explode with anger, as his grin told me that he was planning to wring the very last drop of laughter from the crowd by saying “the Chinese don’t get humor.”

All work is melancholy. No, to be precise, that work “with which we make our living” is melancholy, both in itself and in what it inevitably induces. Melancholy without any hope whatsoever, aside from that of retirement and death. For example, the ones that we know, office workers, estate agents, train crew, computer sellers, gardeners, painters, bird chasers, street entertainers, laughter instigators, aged actors, paunchy police, doctors, church doorkeepers, museum ticket-desk workers, teachers at technical colleges, unemployment benefit claimants, and the countless job-seekers who insist “still not me” or “not me anymore.” If they were aware of how fatally gloomy and ashen their own countenances are. Mao, capture their captured faces and confine them in photographs. I’ll come to get my photo taken again next week.

I took the tram and got off at the station for the museum. The very first thing I saw were countless pigeons blotting out the sky above the heads of wandering dogs. And the large, gorgeously colored scarabs on each leaf of the linden trees. The mutually consistent countenance of each living thing as it swims toward an unspecified bank. An exhibition of life’s tenacity being held in front of the museum. After you buy your ticket and pass through the museum’s entrance to go up the central stairs, you find yourself in a wide hall encircled by six bulging stone pillars, in the center of which there is a bed. An ordinary wooden bed, with a little decoration on the frame done in stone. The air in the hall is chilly, and gives off the scent of the era of stained glass and marble. A man is lying on the bed, stretched out straight underneath a white sheet, sleeping more deeply than anyone else in this world. His head and throat have the appearance of old, friable paper, and his dry puckered lips are slightly parted, his sleeping breath crawling out from between them in the form of a yellow insect. The man and I are the only ones inside the hall. Opening the newspaper one day, I came across a review that had to do with sleep. The body of a sleeping man that had been exhumed from the Parisian hills. The man had been brought here one day as though from a foreign country known as ‘sleep’. No one knows who he is, so people named him “Sleep” and transferred him to the museum. The man is still sleeping.

“This is a part of your respiratory system.” There was a monotonous gaping hole in the photograph that Mao showed me the following week. Because there was only one hole, it looked overly large, overly solitary. Its details shamelessly magnified. A reddish lump of gruesomely inflamed flesh with heinous, swollen protrusions, plump, puffy mucous membrane and pores where filthy fluid had gathered. Mysterious fine dark lines slanted here and there along the gutters of the wrinkled skin. Like metallic arrows inserted into the ugliness of an organic body. I turned my head, unable to look any longer at the brazen pitch-black lumps of flesh paraded in the photograph, a metaphor for “the shamelessness of existence.” Instead, I imagined. Taking money in return for exposing the shameful viscera of human beings makes Mao the photographer no different from the butcher with the same name. I have to send in a photograph like this; that’s what they’d said. A photograph that will be an official testament to my existence, a kind of proxy for me. My photograph will end up among their records. But this photograph isn’t me. It is simply one in the series of “black viscera photographs” taken by Mao, its subject matter and composition determined purely by his own personal tastes. This is Mao and Mao alone. Which also means it is myself “alone.” But Mao declared that “the title of this photograph is ‘Dignified Kiss of Paris Streets.’”

“Even though you said that what you’ve photographed is my respiratory system?”

“That’s right. But the title is ‘Dignified Kiss of Paris Streets.’”

And with that, end of discussion.

Back to the station by the museum. A portion of the museum building was neatly covered by a milky construction cloth. The pigeons and dogs had all disappeared somewhere. Floating dust motes slipped through the wounds of open mouths and quietly took up a place inside. From that day onward I went to the museum daily. This was in order to visit the sleeping man. The man was sleeping as deeply as he always seemed to be, and in what always seemed the same position, with no way to move. At the museum entrance, audio guides resembling lunch boxes with headphones were handed out for visitors to hang around their necks. A title card reading sleep had been set up in front of the bed where the man was sleeping, and below that it read “serial number 228.” If you keyed in 228 to the audio guide you could listen to a commentary on the work. It said that this man was sleeping in front of Mary Magdalene, who, according to myth, had just recovered her senses after witnessing the resurrected Jesus appear before her, say noli me tangere (touch me not), and disappear; this was clearly a lie, an invention of history. Within the vertigo taking over my mind, I imagine: the butcher of sleep, and Mao holding an ax, and the man’s bed floating in mid-air. The square in front of the museum that greets you when you go outside. The optimum place to embrace and kiss and ask after each other’s health if you bump into a former lover in the middle of the street, your high-heeled leather shoes coming to a halt as they carry you to the bus stop. The sunlight falls on beaming lips, moves away from them in a sharp red arc. Oh, how have you been, you whom I haven’t seen in all this time? The street that one can walk down carrying the illusory flowers known as “the passage of time.” Concentric layers of pink petals burst open to reveal their infinitely secret creases. A place where things cannot be otherwise, a place that is rare in this world. Puddles become the eyes of wild animals, scrutinizing our footsteps, and the museum’s glass wall divides the image of the two of us approaching each other into billions of screens. Your former lover’s hand, your former lover’s lips, touch your cold and clammy forehead. A soundless voice. Didn’t you come here every day to look for me? Didn’t you stand here every day in front of me as I slept, key in the number for the audio guide and listen to my voice? The sky, a soft path suspended above our heads along which a plane appeared to collide with a swan as it passed. Five in the afternoon, an interview with the radio scriptwriter on the bus. Microphone and Dictaphone, hot tea in a thermos (for the throat), a spoonful of honey, cough drops, notebook, and pen.

Question: It’s been eight years since you first came here, right?

Response: That’s right.

Question: What brought you here? To put it a little differently, what, to you, is the fundamental difference between being here and being there?

Response: Questions like those. I want to wander in search of the answers to questions like those.

Question: So you’re saying that you deliberately set out to wander in search?

Response: I love wandering in search. It’s my job!

Question: In that case, is it fair to say that you came here (of all places) in order to wander in search of the answer to “Why did I come here (of all places)?”

Response: It’s the same for the question “where did I come from?” Since, in order to wander in search of that answer, I have to have come from “somewhere or other.”

Without a moment’s hesitation, the bus drove right toward the center of the assembled crowd that was blocking the road. The crowd, which had been like water flowing in a smooth, continual current, startled and scattered en masse then, after the bus had gone by, reformed into a line and set off. The passengers on the bus were glassy-eyed, their gazes fixed and expressionless, looking like the heads of pigeons, visible through the bus windows as though in a display cabinet. The demonstrators who were occupying the road dragged their feet as they walked along, heads bent, supporting their foreheads with their hands. Bulky flags covered in unfamiliar letters were wrapped around their bodies, as though these were their clothes. Like monks on fire, like people who had renounced their warm hearts, like fish swimming toward the bank of some gloomy evening river. Are you a Buddhist? the radio broadcaster asked me. We were seated at the back of the bus, and I was watching the retreating figures of the crowd. Are you one of those mendicant Buddhist monks who walk barefoot over heated coals in front of some first-world embassy?

Response: I’m not a mendicant Buddhist monk; the thing is, I have this fear of coming face to face with a clown. The laughter instigator is constantly chasing me. I’m the best comedy material he’s ever found. That is a stroke of luck for him, but bad luck for me. And the worse my luck is, the louder he can laugh. That’s why I arranged to do this interview on a moving bus, you see. What’s worse, he once suggested that we do a street performance together. I would walk along the street, pretending to just be passing by, and he would throw a furry fruit at me. I act completely enraged, taking it as a deliberate insult, and look wildly around me. Until laughter bursts forth from the spectators. Then you’ll continue on your way, he said, and the performance will be over. And no one will have the slightest inkling that it was all staged. And that’s not all. He frequently walks on stilts and wears long trousers, voluminous as the curtain that hangs over a stage. He wants me to be his little puppet. My performance consists of moving as though by strings attached to his hand, pretending to be a wooden doll. He is on stilts, and I am a marionette shedding ridiculous tears. He cannot understand why I refuse such an unconventional proposal for a moneymaking scheme. I am unable to bear the sound of laughter; he doesn’t understand that. He also told me to follow the carnival procession, dressed up as a Mandarin coolie with a pointed straw-hat and a bamboo pole balanced over my shoulders, a basket hanging from each end. I am neither an entertainer nor an actor, I’ve never even thought of becoming such a thing, but he cannot comprehend any of this. I’ve made my thoughts on this matter perfectly clear, a hundred times over, but it seems he doesn’t understand a word I say. Even now he is convinced that it is only right and proper for me to accept his proposal.

Question: In that case, maybe he confused you with someone else? Perhaps a former assistant who ran away, or someone who really does perform as a marionette or Mandarin, or else baggy trousers or stilts, or a circus clarinet. Or what if you are confusing yourself with someone else? It’s highly unlikely, but there are times, now and then, when we encounter someone who knows us better than we know ourselves.

Response: There is something in what you say, but all the same, if there’s one thing in this world that I’m absolutely not, it’s that which the laughter performer thinks I am. That is an indisputable fact, as clear as day. As is the fact that the laughter performer is a stroke of bad luck for me.

Question: It sounds as though you need help.

Response: But can an embassy really help someone like me? Or can a Buddhist? Or a radio broadcast?

Dear listeners, this has been “Portrait of a Foreigner Who Rejects Her Own Identity as Assistant to a Clown,” one of the Portrait of a Foreigner series, from Radio Bremen.

In the bookshop. A stranger spoke into his phone as he brushed past me . . . that will stay with me for a long time. How long? Four days more than eternity. The man moved farther away, disappearing between the stacks with his back hunched like a gorilla’s. As he passed by me, his stooped profile was so similar to that of the snickering laughter performer—part of whose act was to deliberately exaggerate the curve of his back—that I came within an inch of whacking him with the Bertelsmann world atlas I was holding.

On the tram. I took a seat in a foul-smelling corner. The chair’s rustling fabric gave off the smell of wet dog, mixed with the smells of damp skin, urine, and beer. As the tram rattled along, the seats swayed from side to side. A suffocating feeling. The suffocation of laboring between night and day, sleep and wakefulness, constantly swaying from one to the other as the tram swayed along its tracks, seeming to writhe in hope of escape but ultimately as bound by this mechanical repetition as the train is trapped by its tracks. But what would be different, even if you lived in a village above the Himalayan clouds? If our imagination were to remember the boundaries of memory.

I jerk awake as though having been flung forwards on some impact. The sharp air of wakefulness gathered around the bed. Dust and white sunbeams rolling in through the window. The cold palm of wakefulness laid on my forehead. The curious mechanics of being wedged between being awake and having been awoken, between one sleep and another in the repeating cycle. There is no way for me, sleeping, to doubt the fact that I am asleep, but as soon as I am released from sleep, something, a sense of shock and loss that takes my conscious mind by surprise, this body surrounded by hints of forgetfulness. Have I really been asleep? Where was I while I slept? What is it that belonged to my sleeping self? Whispering: your life is made up of things you do not know and things you forget. Of things that you did not live, of your external sleep. All that you have experienced becomes alien as you experience it again through your dreams, your imagining. Thus does your life fly toward you. Fly from all that is fixed, toward a single expression within an unfixed nap. What is sleep, which is a part of real existence just the same as clocks and time are? How can I be sure that the I who is currently speaking the words is not in fact asleep? That day, there was a letter from the embassy in the mailbox. The letter opened its envelope-shaped mouth and read: Dear Frau . . . , you applied for a new identity card and documents. This letter is in response to that application. We have enclosed a copy of the registration documents that we have for you, for you to use as a temporary proof of identity. This temporary ID will be valid for one year; your new proof of identity will be mailed to you during that time.

Though Mao lives in one of adjoining buildings, the lack of a connecting passage means that to get there I have to go downstairs and through the side door we use to take out the trash, skirt the back yard, which is always covered with damp blue-tinged soil, go around the corner and across the parking lot, up the external stairwell, through the metal front door, then up to the fourth floor again. The building comprised a cluster of artist’s studios, with rough walls of exposed concrete. Originally these had been flats rented out by the factory workers, but they now were studio apartments. Mao had no way of locking the door; I always knocked twice before going in. Mao was sitting at the desk in the center of the room. He was wearing a white vest, and nothing else; his usual attire. He was sitting with his left leg propped up on his right knee, peering at a calendar for the following year that was spread open on the desk. Each year, the building’s Artisan Society produced a calendar using its residents’ artwork. This time, Mao had apparently been one of the participants. Mao, I called. He slowly raised his head. Mao, I got something strange in the mail. It doesn’t make any sense, but they’re saying that I’m this person. This person? Mao asked, without moving. Someone named Frau . . . Mao waited, mouth clamped shut, for me to explain some more. He was looking right at me. Behind his back, the window was half open as ever. Open-mouthed, facing the darkened courtyard. What time it was when I woke up, whether this was evening or an overcast afternoon, the gray of damp fog: these are things I didn’t know. Have dreams always been shadowed like this? Do dreams make all people, all objects, appear so distant? Distant scenery, patterns of light and shade like a fixed backdrop. Mao is watching me, as usual, without even a single twitch of his eyelashes. I feel his stare pressing me to continue: So? Don’t you see? They’ve mistaken me for someone else. They think I’m Frau . . . , they want me to get a new ID card using that name. An explanation so futile it made me pluck at my sleeve. Keep this up and before I’m dead I’ll have no sleeves left worth the name. My face burned red, then immediately cooled and stiffened. Insult? Frustration? Emptiness? No, no single word expresses an emotion. Only the emotion itself continues, shading from one to the other, imitating such words in succession. Does Frau . . . think of me? The thought made me raise my head. Is Frau . . . aware of the fact that I am thinking of Frau . . . right now? Is Frau . . . aware of the fact that I am not Frau . . . ? An imaginary candle, burning up and dripping down to its base, body and gaze, bare feet scattering, thrown into confusion by the moving bus. Then Gita, who had been wordlessly crammed into Mao’s bed in a corner of the room, stood up and went to the bathroom, tramping heavily over the clothes that lay strewn across the floor. Gita’s back and buttocks were white and smooth as a cleanly plucked sparrow. This Frau . . . , what was the name again? Mao asked again in a slow, calm tone, as though Gita were invisible, and as though the sound of running water, which had just started up in the bathroom, was not audible. This is her. I went over to Mao and showed him the photo on the temporary ID. Why would they have stuck someone else’s photo on my documents? But the name isn’t yours either. You aren’t Frau . . . Well, of course not. I was still holding the temporary ID that purported to be mine. Mao took the piece of paper from my hand. What I’m saying is, if both the name and the photograph are different, that means it isn’t your ID! I was still somewhat bewildered. I must have woken up at the wrong hour. Or woken up wrong altogether. Peering at the photograph, Mao continued: given that both the name and the photograph are different, given, in other words, that you are not Frau . . . and that this photograph isn’t yours, they must have sent you someone else’s ID by mistake. But it would usually take a fairly long time to get this kind of bureaucratic mistake sorted, especially with you being in a foreign country. An unnecessarily, pointlessly long time. Mao shrugged and turned his gaze back to the calendar. Anyway, he mumbled, I was just about to show you this . . . this is your photograph. Unlike the one on that ID. Mao pointed to the page on which the calendar had been left open. Only then did I flinch, and say, bitterly, “No, that’s not me, you saw me wrong, you or your camera.”

“Even if that were the case, what’s certain is that this is you at the moment the camera went off, even if it isn’t you as you are now.”

Strange. I get the heavy feeling that I had already had this conversation, a conversation identical to this one, a long time ago or from some vantage point very close by—could it have been with Mao? It was a pain more than a conviction, like a crude medieval arrow. The unreal shock of waking abruptly from a long nap, early or late in the afternoon, at some unguessable time. The kind of shock that makes a person yield to insensibility.

“Why do you look so pale all of a sudden?” Mao asked, sounding concerned. “And sad, and like you’ve been sort of . . . ambushed by your frustration . . . why is that?”

“It’s nothing.” I turned and started toward the door. Though Mao made as if to grab my sleeve he quickly changed his mind and lowered his hand back onto the desk, lightly, onto the calendar.

“Come next week. I don’t mind taking your photo again. Then send them that photo, with a letter saying you need a new ID. It will take even longer to get it sorted that way, but how else will they be able to know your face? Since you’re not there; only here.”

I hurried to my familiar sleep, with one arm flung over my face, resting my heavy head on the pillow. My darkness left that place occupied. Clear, bright darkness, artificial, produced by the closing of eyes. My familiar yellow darkness where sporadic fireworks drift about, blurring through my pupils. Small sharp arrows of silver fireworks shot from a bowstring. Metaphysical and opaque scintillations. Signs harbored by my flesh, signs that will never know liberation. Lovely bloodstains.

Frau . . . of Parisian streets, my official, documented self, who is not me.

The laughter performer holding a black clarinet, how old would he have been?

Audio guide number 228: sleep is not a dream. Sleep is not a brief rest. Sleep is not black, sleep neither flows nor pools. Sleep is not dark. Sleep envelops me with thousands of limbs and eyelids, pressing down, sleep closes the thousands of windows inside me one by one. Sleep is not still. Sleep does not subside. Underneath all skin live obscene, fat-bodied larvae. Sleep is compound eyes, is blind moles. Poison poured into tunnels, to kill the moles that dig up the garden. Sleep does not knock on the door of unconsciousness. Sleep goes outside while sleeping, and sleep wakes up from me. And my imagining begins. Please tell me that I’m outside myself now, in a dreamless sleep.

Afternoons, the Parisian streets are made up of humped hills, sweat-soaked milky light, and incessantly chattering peddlers. In the past these hills were a little higher, the gently slanting sunlight a little warmer, and the peddlers a little smaller and shabbier, like tatty marionettes. My past self stood at the foot of the hills, smoking a cigarette and looking down on the Parisian streets. I was with him, but at the time, in our hearts, we each thought we were alone. Thinking about it now, even granted that none of this was ever put into words, it was precisely that thought, that feeling, that was the spirit of the times, the only thing that we felt certain of, and which we acquired internally without the influence of any particular propaganda. And it was through that feeling that we were able to know solidarity, so that we could look each other in the face without fear or anxiety. I look down from the hills at the Parisian streets. The street where peddlers produce such a clamor it’s as though their entire bodies are nothing but mouths, where a performer has his back bent and contorted, where a superior but ridiculous marionette threads its creaking way between them on tall wooden legs. For me, these things defined Paris streets, and the streets I subsequently encountered them in never failed to remind me of Paris streets, to be Paris streets. All the hills that appeared after that day and reminded me of the Paris hills. Hilly streets shaped like prone clams. At the time, we were unable to know that we would come to imagine that day very differently from how it had been in reality, that only within this imagination would we finally come to understand each other. Not only that day, but all the days that we thought (wrongly) had gone by, will reappear and live on, without limit. We’ve probably already discussed this. Topics of conversation brought up inadvertently, simply because they had just popped into our heads. When twenty years or so have passed, how will the air and light and smell of this precise moment have changed? In the future, when around twenty years or so have gone by, the air and light and smell that are passing by us at this very moment—rather, we ourselves who are sweeping by this air and light and smell like a slow train, right this moment—we, or else they, or else everything, will end up flowing past what air and light and smell, to what air and light and smell? After saying the words I laughed, and answered myself: then too, as ever, we will be sitting side by side in this place and smoking. No, this exact moment might already be precisely that moment, all the moments made up of everything that will already have passed away, all the moments that will pass ahead of us. In that case, are we speaking now of the tedious cycle of eternity? Here in this station, at which the train we took by mistake just happened to arrive. At that very moment, like magic, this day of long slow youth grows unspeakably tedious, hills and unknown objects grow so familiar that it is difficult to bear, strangely enough, while crazed by the fact that yesterday, too, we were sitting like this on this very hill and listening to the siren and battle cry of the approaching police car, hideous pulped faces, soundlessly turned pages, faster and faster, the day that was eventually released from this fever, will stiffen faster and faster, without time to age, and bleed, yesterday and yesterday and yesterday, yesterday’s yesterday’s yesterday too . . . I say to him, at some point yesterday’s me will end up meeting you. And in the future too, eternally, Salut. We will be entirely unable to step into other water, Salut. I stopped imagining. Even without imagination we were aware that tomorrow would be no different from yesterday or today. A season filled with the premonition that nothing would change. Fireworks that always come to us too late. We don’t imagine. Even without surreal imagination, it was clear that the Paris streets filled with peddlers, performers, and marionettes, would live forever, constituting ourselves, Salut.

Imagining that, rather than flowing, time only gets piled up infinitely inside us.

Imagining related to Maya. At that time there was “Maya” between us. Maya was the pen name of the woman he had loved since he was in his teens. Even during that season we lived together in the Paris streets, he would read Maya’s books from cover to cover, whatever the content, made an effort to attend each event at which Maya appeared, and even wrote her long letters. As far as I know, though, he never received a reply. I had no idea when he’d met Maya in person or how he’d ended up being invited to her study, her bedroom. To be frank, I didn’t believe for a minute that such things were possible. We were lonely street performers, jobless, whereas Maya was a writer surrounded by admirers, someone who could even be called famous, meaning that however madly in love he was, there was too wide a gulf between them for them to meet in person, for their acquaintance to be actualized. But he talked that down. One day I read an article by Maya in a newspaper. I didn’t yet count myself among her readers, but I bought her latest book because, based on the article, its male protagonist closely resembled him. At this point, quite a long time had already passed since I’d last seen him. So you’re living with Maya! I thought as I read the book. You’re living with Maya! You’ve got her for your own! You’re loved! Maya had drawn him as a shadow behind a veil, but I was able to make him out quite clearly, down to each strand of hair. He appeared to have become Maya’s veiled bride and leaped over old, repetitive eternity in a single step. I imagined an extremely private evening, which he shared with Maya and her young son. The planet of their quiet fireworks. I imagined Maya’s soft small breasts, pillowed on my stomach. How precisely those things which are lived are worth writing about. Salut.

You might want to change your clothes, Frau . . . , Mao said, producing a gray dress flecked with gold as I stepped into the studio. I took it and was heading for the bathroom when I suddenly got the feeling that something was wrong. I turned back and stared at Mao. I’m not Frau . . . , I’m telling you. That’s precisely why I need to have another ID photo taken.

“That was only a little joke. I was trying to cheer you up. So laugh. Go on, crack a smile at least.”

I tried to give the appearance of laughing, but it didn’t come off well.

“Mao, we’ve already known each other for eight years or so.” I’d left the bathroom door open while I was getting changed, and raised my voice so that Mao could hear me. At the same time, I strained every nerve to ensure that those words sounded as though they carried no weight whatsoever. Which was in fact the case. Not that I strained my nerves, but that those words had no weight whatsoever.

“All because you showed up one day, as suddenly as if you’d fallen from the sky,” Mao responded cheerily while he got his camera ready. “It’s all your fault.”

Me: Frau . . . is not some ladybug who suddenly fell from the sky. Only the innocent by-product of a bureaucratic process. No one who knows where she came from, who she is, which is entirely to be expected. To put it concretely, her hometown is documents. When, at a certain point in time, fragments of documents that have lost their owner and have been wandering aimlessly ever since happen to come together and form a person, an individual by the name of Frau . . . will naturally end up being born, without anyone having intended it.

Mao: An individual who just happens to be registered at your address.

Me: My address and my profile and my proof of identity.

“I see.” Mao nodded vigorously. I couldn’t tell when he had taken the picture.

I imagine the day when I first met Mao. That day, Mao had a woman with him. This is Gita, my ex-girlfriend. Her gold and gray off-the-shoulder dress had a faint luster and looked like stripped skin; each time she took a step forward, she came off as intentionally haughty or coquettish. But Gita wore a complex facial expression as well as the dress. As though she was worried that, in the future, I would end up wearing this dress which she so liked. Since Mao only had the one dress for his female subjects to pose in.

I imagine the day when I first met Mao. I was on the Paris hills. In each small square and at each corner, peddlers had their wares laid out, and the countless people roaming what looked like Sunday’s flea market, oh yes, that was it, roaming the flea market, each looked to have made themselves up like a performer, identical. A performer from a bygone age, but I can’t be sure that time really does flit “past” us on its two feet. The water of memory flows, but isn’t it the case that our faces submerged within it are often not our own? And so it would not have surprised me in the least if Mao were to have come toward me towering over two meters tall, holding a black circus clarinet and made up as a white-faced performer in a blue gown, moving slowly through the crowd. Standing there in front of the museum I would have shown no surprise, but rather looked straight at him and even—if I’d wanted to—smiled.

What with the white make-up and white conical hat, roundish at the end, Mao’s head looked like one great big chicken egg. He had painstakingly painted his lips red, and his right eyebrow was made up with the thick black-colored cosmetic characteristic of whiteface performers. His left eyebrow had been shaved so drastically as to be almost invisible. The blue gown he was wearing had sleeves whose shoulders billowed out like jars, and its neckline was decorated with artificial pearls. Waving the black clarinet like a baton as he walked in his bright gray shoes, he looked majestic, every inch the commanding officer of the performers. And so it will not be surprise me even if I fall back in love with him. Because I have never seen a whiteface performer, never embraced a white-faced performer, never affectionately kissed a whiteface performer who has only one thick, black eyebrow. I moved toward him and did it all just as I had imagined. And I spoke his name, Mao, Mao, Mao, my Mao. We held hands and were quiet for a while. His expression masked by his makeup, Mao waved his hand in the direction of the museum and said, we will end up entering that place. Inside it I will take your photograph. Your sleep, called Dignified Kiss of Paris Streets. His mouth twitched curiously as though he was on the point of bursting into laughter. Mao, you won’t photograph me in an ugly way? Promise me that you won’t make me a laughingstock. I begged him like this because I was worried, but what is ugliness and what is beauty? I only ceaselessly imagine that day when I first met Mao. Each time I enter a new sleep that day reveals itself before me. Three women approach from the far side of the fields, walking side by side; each are wearing dresses, and one of them is me. We three women stretch out our arms from our sides and clasp each other’s hands. Me and Gita, and—surprisingly—Maya’s cold hand. The fluttering hems of our dresses are wet with the evening dew, and the sky is dense with stars. The moon is at our backs, and the camera, suspended in midair from a crane, photographs our shadows. Our faces concealed by our hanging hair. A parade of masked empresses, wings attached to our backs. We, women.

Mao, who detests the news and all media, cannot set eyes on a newspaper stand without making some cynical remark. Babbling excitedly about the bastards who, seeing that North Korea’s nuclear weapons and the melting glaciers mean that we are all doomed to die, are rushing to the banks to get a low-interest long-term residency loan for two hundred years! But Mao, newspapers don’t always print such nonsense. I’m reading a different article. An article that isn’t fear mongering, an article about an item disappearing from a museum exhibit. Serial number 228 – Sleeping Man, a find excavated from the Paris hills, woke up one day and went off somewhere (people, I am truly not in the least surprised). He would have climbed down from the bed, crossed the deserted exhibition hall, passed through the entrance hall, and walked down the stairs. His would have been a slightly stooped and awkward gait, but no one would have been observing him carefully, so if he had slipped into the crowd as he left the museum no one would have been able to tell that he was serial number 228 (even if that they had, something else would have been come up to distract them). The sight of you from long ago, standing at the bus stop, absent-minded as ever, with both hands thrust into the pockets of your shabby old jacket. The bus is coming. I feel my body swaying and gradually thinning out in the sunlight. I will become invisible, and all that will eventually remain in the wind are the flowers from the pot I had been carrying.

The chairs in the waiting area had bumpy plastic surfaces, so the pen made a crunching sound as it staggered over the paper. The digital clock on the wall of the government office showed twenty-five minutes past four in the afternoon. Confusing that with the date, I was on the verge of writing down April 25th on the documents for Frau . . . when I realized my mistake. But where do I have to hand in this application form? Each counter window had a number, and the numbers went up to at least 41 (Frau . . . could not see as far as the higher numbers). It seems like all the information windows in the world have gathered here! After handing in the application and getting a receipt you have to take that to the office on the first floor and get an official note of confirmation. If you come back again two weeks later with that note, you will be able to obtain a certificate of registration. When you come to get that certificate, remember to bring your old proof of identity, your newly issued temporary proof of identity, your certificate of stay in the country and the permit, a copy of your bank statement, license, registration certificate for your place of residence, written confirmation from the police, medical insurance . . . people are hovering hesitantly around chairs and sofas in the waiting area. They are all reluctant to approach the counter, wanting someone else to stride up first and grandly present their documents. Where did all these people come from? Where did they come from, and where do they want to go? The civil servants at the counter wait contentedly, sitting slightly askew, both hands in their pockets. Waiting not for the applicants to approach them, but for the end of the period during which these applicants are permitted to come for an interview. For the conclusion of a lawful and natural administration. In the glare from the electric lights their eyes gleam faintly behind spectacle lenses, beyond the glass partition bearing the government logo. “According to the constitution, all citizens have the right of residence and the right to work, with the exception only of those cases in which the base of livelihood cannot be sufficiently provided, and thus society at large ends up shouldering the burden; where there are factors that endanger the security of society at large, or where such rights must be curtailed in order to prevent infringements upon efficiency, good morals, and manners; or to soundly safeguard the institutions of marriage, family, and collective culture (from Peter Handke’s ‘The three Readings of the Law’).” Frau . . . peers once more at her clumsy-looking application documents. Such meager content doesn’t seem likely to secure her any type of permission at all. Not even for something as trivial as getting a new photo taken, that is. Her old documents will already have been posted somewhere, and the new documents haven’t even been handed in yet. This time gap, in which she doesn’t exist on paper, binds her like a chain. The door opens and closes incessantly, and the congregation swells. Mute supplicants, enough to fill the hall. Applicants spanning a lifetime. Applicants who are not tall, who stand there not saying a single word, concealing their thoughts and feelings, hesitating within the commotion of silence. Breathing deeply, Frau . . . looks up. There are small ventilation holes in the ceiling at regular intervals, which look like speakers. Or are they an ordinary fire-sprinkler system? Punishing all heat with water. She imagines water pouring down from above and sweeping away her documents, sweeping away the documents of all the people gathered there, sweeping away the smiles of the civil servants sitting at the counter windows, extinguishing the hard fossils of faces that wanted to keep living, the electricity wires and electric storage equipment, the telephones and telegram stationery, filling up the hall of time and overflowing without limit. If that happened, my documents would set free of me. They would be able to go to wherever they want. To be whatever they want to be. Frau . . . put her name and signature at the bottom of the document. As soon as the tears spill from my eyes, lascivious laughter bursts out from among tired, bored tourists with mugs of yellow beer set in front of them, as though they had been waiting for something of the sort. They who have suddenly grown ancient in this moment, their hair turning gray and their teeth falling out. Where did they come from, and where do they want to go? Twilight is falling outside the window, and the civil servants are preparing to go home.

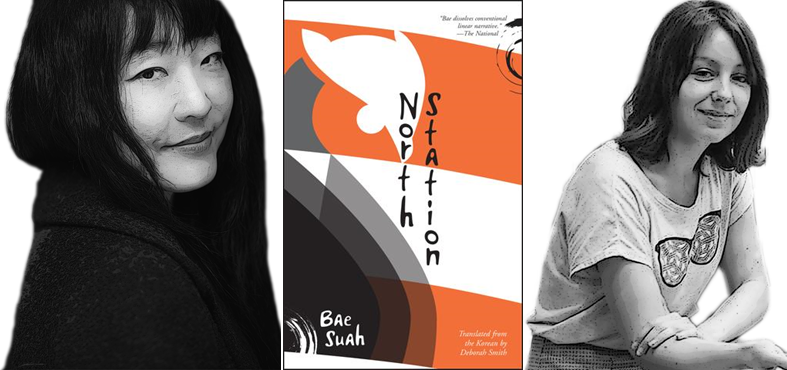

Bae Suah, one of the most highly acclaimed contemporary Korean authors, has published more than a dozen works and won several prestigious awards. She has also translated several books from the German, including works by W. G. Sebald, Franz Kafka, and Jenny Erpenbeck. Her first book to appear in English, Nowhere to be Found, was longlisted for a PEN Translation Prize and the Best Translated Book Award.

Deborah Smith’s other literary translations from the Korean include two novels by Han Kang (The Vegetarian and Human Acts), and two by Bae Suah (A Greater Music and Recitation). She also founded Tilted Axis Press to bring more works from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East into English.

This excerpt from North Station is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © 2017 Bae Suah. Translation copyright © 2017 Deborah Smith.

Published on October 2, 2017.