This essay is part of Morten Høi Jensen’s column European Diarist.

The first book I read after President Trump’s inauguration in January was Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, considered by some the greatest of all Great American Novels. I first read it many years ago but came away preferring Herzog or Humboldt’s Gift, novels in which the abundance and energy, the jazzy, freewheeling rhythms of Bellow’s prose, mysteriously, seemed somehow more measured. In Augie March, by comparison, Bellow’s sentences appeared always about to run away from their author, as a dog might stretch its leash only to be yanked irritably back in formation.

But how gloriously they stretch! Famously, there is the description, early in the novel, of Augie and his friend Jimmy working as elevator operators at City Hall in Chicago, where they “rose and dropped, rubbing elbows with bigshots and operators, commissioners, grabbers, heelers, tipsters, hoodlums, wolves, fixers, plaintiffs, flatfeet, men in Western hats and women in lizard shoes and fur coats…” But there is also, much later, Augie’s view of Chicago from the window of a high-rise apartment building: “the gray snarled city with the hard black straps of rails, enormous industry coking and its vapor shuddering to the air, the climb and fall of its stages in construction or demolition like mesas, and on these the different powers and sub-powers crouched and watched like sphinxes. Terrible dumbness covered it, like a judgment that would never find its word.”

Rereading Augie March, I was reminded of how Bellow’s novels had helped convince me—when I was in still high school, in Copenhagen—that I simply had to live among all of the concrete and steel, the neon signs and billboards, the pluralism of the many-faced humanity of an American metropolis. Because I often read Bellow while listening to Thelonious Monk’s Criss-Cross, I always connected his writing to that uniquely American art form—jazz—whose spiritual home, after all, is the big city. The sentiment of Augie March’s famous opening sentence could just as well be the artistic credo of any number of great American jazz musicians: “I am an American, Chicago born — Chicago, that somber city — and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way…”

One of the central conflicts of Bellow’s novels is the apparent incommensurability of Old World thinking with the demonic pace of American society. The country’s big cities become a sort of battleground of Big Ideas. Bellow once wrote movingly of his discovery of the classics of European literature and philosophy as a young man darting about the streets of Depression-era Chicago:

I was soon aware that in the view of advanced European thinkers, the cultural expectations of a young man from Chicago, that center of brutal materialism, were bound to be disappointed. Put together the slaughterhouses, the steel mills, the freight yards, the primitive bungalows of the industrial villages that comprised the city, the gloom of the financial district, the ballparks and prizefights, the machine politicians, the prohibition gang wars, and you had a solid cover of “Social-Darwinist” darkness, impenetrable by the rays of culture.

Mercifully, there is no Social-Darwinist darkness in The Adventures of Augie March — no determinism, no fixed fate. The novel, with its picaresque, Twain-hinting title, has more than just a streak of American individualism about it: Augie is finally exasperated by the “big personalities, destiny molders, and heavy-water brains” he encounters in both life and books. “There’s too much of everything of this kind,” he says, “too much history and culture to keep track of, too many details, too much news, too much example, too much influence, too many guys who tell you to be as they are, and all this hugeness, abundance, turbulence, Niagara Falls torment.”

For all it meant to him as a Jewish immigrant, Bellow was ambiguous about the leveling quality of American democracy. He retained an almost religious, Old World interest in matters of intellect and soul, deriding what in The Dean’s December the narrator calls the “soft nihilism” of American society (as opposed to the “hard nihilism” of Communist Romania): the anti-intellectualism and materialism, the TV culture and celebrity worship, the whole “moronic inferno,” to use a phrase of Wyndham Lewis’s that Bellow was fond of.

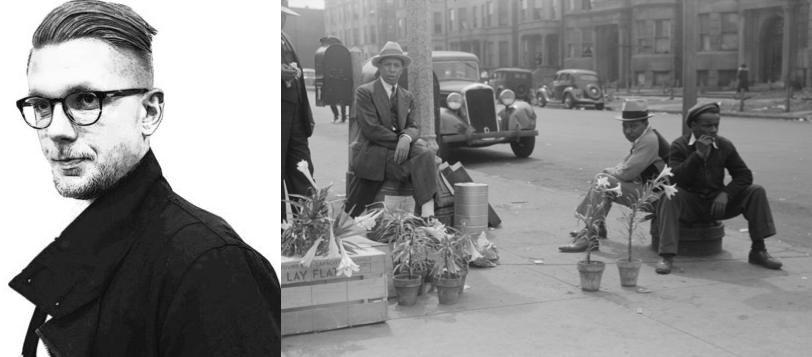

There was, to be sure, an old man’s lament about these quarrels (Bellow, late in life, wrote a foreword to Allen Bloom’s conservative polemic The Closing of the American Mind), but more notably, there was a novelist’s concern for the individual human being over the sweeping prescriptions of ideology and the pressures of technological advancement. “The soul,” Bellow said, “has to find and hold its ground against hostile forces, sometimes embodied in ideas which frequently deny its very existence, and which indeed often seem to be trying to annul it altogether.” He did not pine for the hierarchies and traditions of the European continent; his novels unmistakably quicken to the pulse of American modernity. Like Whitman, he was exhilarated by the “surplus and superabundance of human material” cities like New York and Chicago offered. By extension, I find it difficult not to read The Adventures of Augie March as a kind of paean to the immigrant and minority life it depicts: the Chicago of Jews, blacks, Poles, Norwegians, Germans, Mexicans, Asians, Italians, Lithuanians, and Swedes.

With his quick, Dickensian gift for portraiture and his interest in “Machiavellis and wizard evildoers, big-wheels and imposers-upon,” what would Bellow the novelist have made of a Trump presidency? Not much, I suspect. (I know of only a single reference to Trump in Bellow’s oeuvre: in the late novella The Actual, when a luxury hotel trillionaire is said to have a name that is “instantly recognizable, like Prince Charles or Donald Trump.”) Bellow’s interest was always for “higher-thought clowns,” not no-thought clowns. The trajectory of Trump’s journey from corrupt-realtor-turned-reality-TV-star to President of the United States, on the other hand, might have interested him for what it says about the moral and intellectual decline of America’s political class. A sentence in the opening paragraph of Ravelstein, Bellow’s last novel (published in 2000, when its author was 85), prophetically reads: “Anyone who wants to govern the country has to entertain it.”

In that same novel, the eponymous hero, a professor of political philosophy, asks his students: “With what, in this modern democracy, will you meet the demands of your soul?” It is one of the many joys of reading Bellow’s novels that such a question comes to sound not archaic, but urgent. Pascal said that kings are surrounded by people who take great care never to let them alone and think about themselves. In a late essay, Bellow argued that the Age of Information has made kings of us all, lordly distracted by our willing court of electronic instruments. He argued that writers, themselves children of distraction, are uniquely qualified to remind us, the distracted multitudes, of what Augie March calls “doing the indispensable work”:

It takes a time like this for you to find out how sore your heart has been, and, moreover, all the while you thought you were going around idle terribly hard work was taking place. Hard, hard work, excavating and digging, mining, moling through tunnels, heaving, pushing, moving rock, working, working, working, working, working, panting, hauling, hoisting. And none of this work is seen from the outside. It’s internally done. It happens because you are powerless and unable to get anywhere, to obtain justice or have requital, and therefore in yourself, you labor, you wage and combat, settle scores, remember insults, fight, reply, deny, blab, denounce, triumph, outwit, overcome, vindicate, cry, persist, absolve, die and rise again. All by yourself! Where is everybody? Inside your breast and skin, the entire cast.

Morten Høi Jensen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He has contributed to the Los Angeles Review of Books, Salon, and The New Republic, and is the author of a forthcoming biography, A Difficult Death: The Life and Work of Jens Peter Jacobsen, due out from Yale University Press in the fall of 2017.

Photo: Morten Høi Jensen, Private

Photo: African American lily vendors on Easter Sunday, Chicago, Illinois. April 1941, Everett Historical | Shutterstock

Published on July 6, 2017.