This is part of our special feature The Gender of Power.

Two Regions Diverge

In the last two decades, Western European nations have enjoyed mostly steady progress towards the acceptance of homosexuality.[1] For their Eastern European counterparts, however, negative attitudes and intolerance toward homosexuality and homosexual people, or homonegativity [2], continue to be remarkably high, with some nations experiencing stagnation or even regression in acceptance in recent years.[3] Gay rights movements have been met with repression and harsh cultural resistance.[4] We can see this particularly in the recent violence toward LGBT persons in Chechnya, an overall rise in relevant hate crimes across the region, and even increases in legal measures to discriminate against this group.

In general, Western nations have done little to address the rise in the persecution of LGBT persons in the region, though media occasionally offers us glimpses of the problem when tensions flare. For example, the West expressed disapproval when Russian parliament passed a bill criminalizing the “promotion of non-traditional sexuality” to minors, just before the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. Global attention to the issue quickly died down, and protests achieved little. Now, in the Chechen Republic, police forces have detained and brutally tortured over one hundred men in a violent “anti-gay” campaign. Many have fled their homes and even the country in an attempt to escape the purge. Though Russia has pledged to investigate these offenses, President Vladimir Putin continues to deny that homosexuals face any persecution in Russia at all. Ramzan Kadyrov, the Head of the Chechen Republic, responded in an interview by denying the ongoing violence, arguing that “there are no gay men in Chechnya…you can’t detain and repress people who simply don’t exist in the republic.”[5]

Tracking Homonegativity

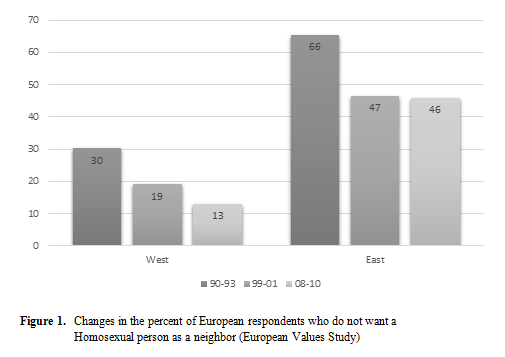

Public opinion surveys provide us with crucial insights on this issue. For decades now, the European and World Values surveys have been asking respondents about their tolerance toward various groups. The divergence between patterns over time in Western and Eastern European nations has been striking. Below we present data for countries in the European Values Study (EVS)[6] from 1990-2010. Among Western nations (i.e., Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Great Britain, and Northern Ireland), intolerance toward homosexual neighbors has dropped from an average of 30 percent to 13 percent. In the East (i.e., Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia), initial large drops in homonegativity between the early and late 90s stagnated. As of 2010, average intolerance for homosexual neighbors was as high as it had been in the previous decade, and much higher than it ever was in the Western sample.

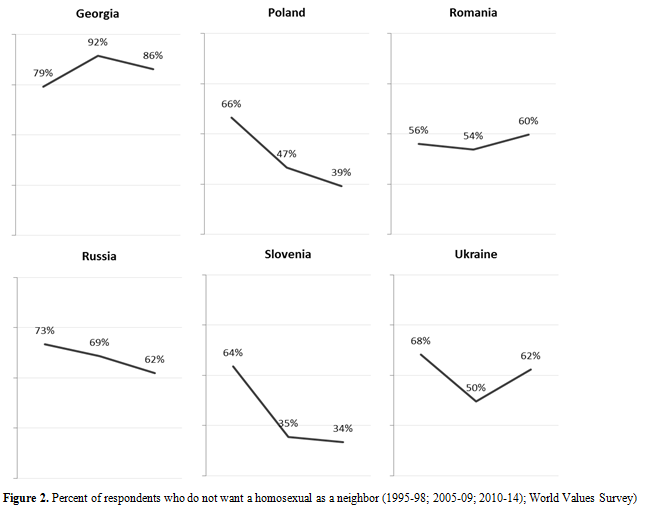

As we discuss further below, national averages vary, but in the most recent time period of this EVS survey, only one Western nation (Portugal, 27 percent) had greater homonegativity than an Eastern nation (Czech Republic, 23 percent). Further, it is important to note that even in 2010, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Estonia saw increases in the percent of people mentioning homosexuals as undesirable neighbors from the previous time period. As these older patterns make clear, the rising homonegativity and anti-homosexual violence we see occurring now has much deeper roots.[7] To understand where more current opinion stands in Eastern Europe and post-communist nations, we focus on a sub-sample of six countries with data across thirty years from the World Values Survey.[8] These patterns highlight the diversity of opinion change in these nations, but also the much greater, sustained homonegativity in each as compared to the Western European trend.

Within the sample of Western European nations available in the most recent period (Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden), homonegativity is very low at only 10 percent on average. This is a decline from 18 percent in wave one and 14 percent in wave two. In comparison, the patterns in the six Eastern nations show that intolerance has declined in Poland, Russia, and Slovenia, but not in Georgia, Romania, or the Ukraine. Even in the most tolerant nation, Slovenia, the recent survey wave indicates that 34 percent do not want a homosexual neighbor, 15 percent more so than in Germany (19 percent), the most homonegative Western nation in that wave. At the other end of the spectrum, the vast majority of Georgians (86 percent) do not want a homosexual neighbor, though this is down from a high of 92 percent in the 2005-2009 wave. These trends again show that intolerance is extremely high and declining slowly – if at all.

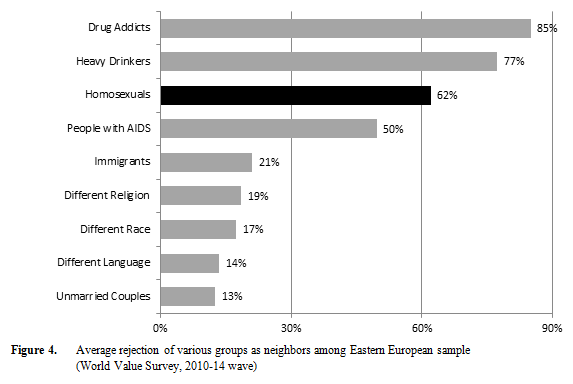

We can see that, on average, intolerance toward homosexuals is quite similar to that of drug addicts and heavy drinkers, and even slightly greater than for people with AIDS. This suggests that respondents are using a homonegative framework that identifies homosexuals as a group that is immoral, dangerous, and diseased, and may consider homosexuality a personal failing. In comparison, although Western Europeans also see alcohol and drug addicts as undesirable neighbors (mentioned 65 percent and 77 percent of the time in the most recent wave, respectively), no other groups are perceived with such intolerance.[9]

At the Root of the Rift

As seen above, homonegativity is framed quite differently in Eastern versus Western Europe. In the Western nations, having a homosexual neighbor is very rarely seen as a problem, and if so, it is grouped with kinds of intolerance toward social groups that are “different” due to more or less stable character traits – for example, people who speak a different language, come from a different racial or ethnic background, or practice a different religion. In comparison, intolerance toward homosexuality in Eastern Europe is associated with perceptions of threat, failed morals, and consequences of personal choice, such as heavy drinking, drug addiction, and AIDS infection. Thus, intolerance in the West appears to reflect social anxiety around difference, while in the Eastern nations, homosexuality is deemed a moral or physical danger. This echoes other work arguing that homonegativity differs from – and is exceptionally high in comparison to – other kinds of intolerance or opinions on sexuality in Eastern Europe.[10]

Why do these regions diverge so strongly? Obviously, the answer is complex, but research has offered a number of important insights. Homonegativity stems in part from religiosity, economic (in)security, and uneven educational opportunities.[11] In post-communist Eastern European states, uneven transitions to democracy and cultural inflexibility also play a role.[12] But although we know that homosexuality has been heavily politicized, the influence of individual political perspectives is often missing in studies of homonegativity in the East. We argue for expanding academic work to include greater emphasis on broader political orientations. Without doing so, we risk underestimating the extent to which homonegativity is grounded in political ideology and experiences. Such issues become even more important to understand as Russia asserts its dominance in the region, and as Eastern European nations cope with disillusionment with democratic progress in the region.[13]

In a thought-provoking argument for a more nuanced view of Vladmir Putin and Russia’s place in world order, Christopher Caldwell, Senior Editor of The Weekly Standard, illustrates the importance of understanding different political orientations.[14] Alluding to an overall rejection of “Western” expectations, he quotes historian Walter Laqueur’s statement that “most Russians have come to believe that democracy is what happened in their country between 1990 and 2000, and they do not want any more of it.” (7). If not rejecting democracy, we do see that many Eastern Europeans show a strong skepticism about what democracy means and how it may be tied to forces threatening cultural, political, and economic stability – and how the efforts of LGBT movements fit into this narrative.[15]

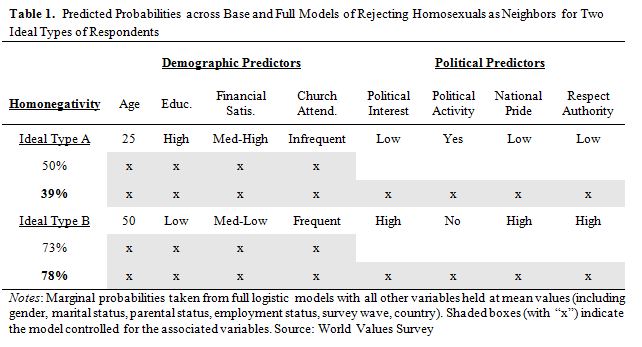

While a full examination of the political correlates of homonegativity is beyond the scope of this piece, our analysis suggests the importance of continued research in this vein. Our models show that, on average, and as expected, younger, more highly educated, more financially secure, and less religious persons are more tolerant of homosexuals. However, when we also test the importance of political orientations, we find that these matter nearly as much as demographic factors. Respondents who have engaged in at least one form of political activism (e.g., signing a petition, demonstrating, or boycotting), who have lower national pride, and who reject the need to respect authority are about 16 percent less likely to mention homosexuals as undesirable neighbors. Combining these effects shows a significantly large gap. The most tolerant have only a 39 percent probability of mentioning homosexuals, while the least tolerant have a 78 percent probability of homonegativity. Altogether, this tells us that there are deep demographic and political cleavages in these nations that are reflected at the individual level. The variation among residents within Eastern Europe should not be ignored, and broad claims will underestimate sources of support for LGBT rights and recognition.

With regard to variation across countries, the patterns are less apparent. Two of the least homonegative nations – Slovenia and Poland – are members of the European Union, but Romania joined the EU in 2007 and has not seen declining homonegativity in the most recent survey wave. None of the six nations differ greatly in average age or educational attainment, though Slovenia and Poland each have residents who are more satisfied with their financial situation, on average. Church attendance and nationalism also do not strongly demarcate differences among the most or least homonegative nations. Slovenia and Poland tend to have somewhat lower emphasis on authority, and more political activism. Overall, these patterns suggest that variation within these nations must be a central area of inquiry, as these national proportions/averages clearly mask large cleavages.

Looking Ahead

Stagnating and declining of tolerance toward homosexuality in Eastern Europe should be alarming to anyone taking note of changes in Europe. It represents not only disparate perspectives on sexuality and freedom of personal identity, but also signifies a cultural and political rift between Western and Eastern Europe that may be deepening. Growing intolerance could be a symptom of a dangerous divide between East and West, rooted in political disenchantment and subsequent mutual rejection. Eastern Europeans’ rejection of the West may be translating into hostility towards anything “Western” and consequently, people that behave in “Western” ways. If this is true, then demographic and economic change alone may not be enough to push change. Reducing homonegativity, violence, and stigma may require grassroots and locally relevant cultural frameworks that help dispel marginalizing views and foster general respect for fellow citizens.

Dissimilar political and emotional standpoints will surely be a challenge. Even here, we are guilty of analyzing Eastern homonegativity through a Western lens. Without willing dialogue, we seem to fall into a trap in which the West accuses and the East denies. For Eastern Europeans who feel as though their voices went unheard under communist rule and failed promises of democratic prosperity, it will be easy to interpret criticism from the West as contempt and meddling. If we hope to advance understanding of these issues and to help effect relevant policy change, we must recognize and apply the Eastern European perspective. Without this, social movements born in the West will further fail to appeal to Eastern Europeans and in turn, Easterners may further feel misunderstood and alienated by the West.

A good next step would be to more accurately identify the roots of this intolerance. Fluctuations in homonegativity in Eastern Europe do not simply vary with religious preference, culture, education, joining the European Union, or adapting “progressive” human rights. There is something more, which we hope to explore by incorporating political orientations and ideas about activism. We plan to take a closer look at the more personal, individual political drivers of homonegativity in an effort to help piece together the growing crisis in the region, which urgently requires our attention and resolve.

Catherine Bolzendahl is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. Her research intersects with political sociology and the sociology of gender. She co-authored an award-winning book on American definitions of same-sex family, and has published several articles in peer-reviewed journals, including European Sociological Review, British Journal of Sociology, Gender & Society, and Social Politics.

Ksenia Gracheva is pursuing a PhD at the University of California Irvine School of Law. Her research investigates the complex interplay between innovations in the pharmaceutical industry and evolving perceptions of gendered responsibility, building an empirical foundation for a new approach to policy analysis and encouraging advocacy for reproductive health policies that reflect public interest.

Photo: LGBT Column demonstration in St. Petersburg on May 1 against the war in Ukraine and Russia

References:

[1] See work by Alexander, Amy C., Ronald Inglehart, and Christian Welzel. 2016. “Emancipating Sexuality: Breakthroughs into a Bulwark of Tradition.” Social Indicators Research 129(2):909-35.; van den Akker, Hanneke, Rozemarijn van der Ploeg, and Peer Scheepers. 2013. “Disapproval of Homosexuality: Comparative Research on Individual and National Determinants of Disapproval of Homosexuality in 20 European Countries.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25(1):64-86; Gerhards, Jürgen. 2010. “Non-Discrimination towards Homosexuality: The European Union’s Policy and Citizens’ Attitudes towards Homosexuality in 27 European Countries.” International Sociology 25(1):5-28.

[2] Research on opposition to homosexuality uses divergent terms, and may vary by sub-field. We find the term homonegativity to provide more flexibility in capturing the multidimensionality of anti-homosexual responses, as also discussed in Lottes, Ilsa L., and Eric Anthony Grollman. 2010. “Conceptualization and Assessment of Homonegativity.” International Journal of Sexual Health 22(4):219-33.

[3] Andersen, Robert, and Tina Fetner. 2008. “Economic Inequality and Intolerance: Attitudes toward Homosexuality in 35 Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 52(4):942-58; van den Akker, Hanneke, Rozemarijn van der Ploeg, and Peer Scheepers. 2013. “Disapproval of Homosexuality: Comparative Research on Individual and National Determinants of Disapproval of Homosexuality in 20 European Countries.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25(1):64-86.

[4] Ayoub, Phillip M. 2014. “With Arms Wide Shut: Threat Perception, Norm Reception, and Mobilized Resistance to LGBT Rights.” Journal of Human Rights 13(3):337-62; Holzhacker, Ronald. 2012. “National and transnational strategies of LGBT civil society organizations in different political environments: Modes of interaction in Western and Eastern Europe for equality.” Comparative European Politics 10(1):23-47.

[5] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39779491; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/26/russia-investigates-gay-purge-in-chechnya

[6] http://www.europeanvaluesstudy.eu/

[7] See also: Lipka, Michael. 2013. “Eastern and Western Europe divided over gay marriage, homosexuality.” Facttank: News in the Numbers (http://pewrsr.ch/1du6kF8): Pew Research Center.

[8] http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp

[9] Figures come from the most recent World Values Survey wave and include data from Finland, Germany, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and Great Britain. Immigrants come next at 15% mentioning not wanting them as neighbors, followed by those with AIDS (13%), homosexuals and those with a different language (both 10%), those of a different race (9%), a different religion (6%), and unmarried couples (3%).

[10] Andersen, Robert, and Tina Fetner. 2008. “Economic Inequality and Intolerance: Attitudes toward Homosexuality in 35 Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 52(4):942-58; Lipka, Michael. 2013. “Eastern and Western Europe divided over gay marriage, homosexuality.” Facttank: News in the Numbers (http://pewrsr.ch/1du6kF8): Pew Research Center.; Štulhofer, Aleksandar, and Theo Sandfort. 2005. “Introduction: Sexuality and Gender in Times of Transition.” Pp. 1-25 in Sexuality and Gender in Postcommunist Eastern Europe and Russia, edited by Aleksandar Štulhofer and Theo Sandfort. New York: The Haworth Press.

[11] Alexander, Amy C., Ronald Inglehart, and Christian Welzel. 2016. “Emancipating Sexuality: Breakthroughs into a Bulwark of Tradition.” Social Indicators Research 129(2):909-35.; Gerhards, Jürgen. 2010. “Non-Discrimination towards Homosexuality: The European Union’s Policy and Citizens’ Attitudes towards Homosexuality in 27 European Countries.” International Sociology 25(1):5-28; Štulhofer, Aleksander, and Ivan Rimac. 2009. “Determinants of Homonegativity in Europe.” The Journal of Sex Research 46(1):24-32.

[12] Kulpa, Robert, and Joanna Mizielinska. 2012. De-centering western sexualities: Central and Eastern European perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

[13] http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/10/9-key-findings-about-religion-and-politics-in-central-and-eastern-europe/ft_17-05-08_easterneurope_russia/

[14] Caldwell, Christopher. 2017. “How to Think about Vladimir Putin.” Imprimis 46(3): 1-7. https://imprimis.hillsdale.edu/how-to-think-about-vladimir-putin/

[15] Bolzendahl, Catherine, and Hilde Coffé. 2013. “Are ‘Good’ Citizens ‘Good’ Participants? Testing Citizenship Norms and Political Participation across 25 Nations.” Political Studies 61:45-65; Rohrich, Kyle James. 2015. “Human Rights Diplomacy amidst “World War LGBT”: Re-examining Western Promotion of LGBT Rights in Light of the “Traditional Values” Discourse.” Pp. 69-96 in Transatlantic Perspectives on Diplomacy and Diversity, edited by Anthony Chase. New York, NY: Humanity in Action Press; Shevtsova, Maryna. 2017. “Queering Gezi and Maidan: Instrumentalization and Negotiation of Sexuality within the Protest Movement.” Pp. 85-100 in Non-Western Social Movements and Participatory Democracy: Protest in the Age of Transnationalism, edited by Ekim Arbatli and Dina Rosenberg. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Published on July 6, 2017.