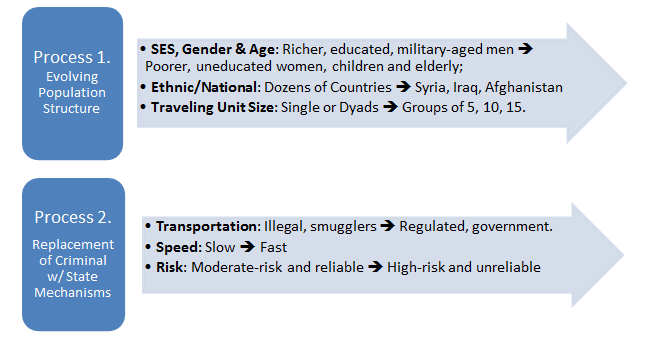

From the Vatican to Downing Street, the refugee crisis has been acknowledged as a fundamental test of European politics and identity. Yet the refugee wave that shook the continent has yet to be understood as a dynamic sequence. I argue that the historic migration of mid-2014 to 2016 on the Balkan Route is best understood as the unfolding of two parallel processes: (1) the evolving population structure of the migrant population; and (2) the gradual replacement of criminal mechanisms of migration with government mechanisms. This article offers a preliminary sketch of these interrelated processes, which will likely define future refugee waves.

Bottom-Up Research

Many on-the-ground developments of the migrant crisis have caught Europe by surprise because of a dearth of bottom-up inquiry. With fieldwork in Jordan, Turkey, Greece, Serbia, and Germany, I have led a team of researchers to conduct in-depth interviews, surveys, and ethnography in every major refugee hotspot on the Balkan Route. We sampled hundreds of Syrian refugees, and interviewed camp volunteers, medical staff, NGO representatives, soldiers, and policemen. We learned in detail about migrants’ step-by-step journey through Europe, and their interactions with smugglers, officials, and other refugees. Our data sheds unique light on how the wave unfolded over time, and what can be learned for the future.

Refugee Wave in Context

The “refugee wave” here refers only to migrants entering the European continent between July 2014 and March 2016, when the Balkan Route was closed. I further refer to an earlier phase of the flow, when subjects’ trailblazer relatives and friends traveled the Balkan Route, and a later phase, during which our fieldwork was conducted. I draw attention to the refugee flow as a dynamic, evolving development—not a static event. Changes between the earlier and later phase were incremental and partial. Nevertheless, I argue that two concurrent processes occurred: the population structure evolved (the people constituting the flow changed) and criminal mechanisms of migration were replaced with state ones (the journey changed).

The Balkan Route

The Balkan Route was practically the only channel enabling the two-year migrant influx into Europe. Of the near-million refugees that reached Germany in 2015, 800,000 of them passed through the Route (UNHCR 2015). Of those, 600,000 were registered at Preševo Center in Serbia, the rest preceded or bypassed it (UNHCR Belgrade Office 2015). The overemphasized alternative routes—from north Africa into Italy, France, or Spain—accounted for a minor share of the overall influx in this period. The overwhelming majority of refugees entering Europe did so through the Balkan Route.

The Route consists—in sequence from Turkey—of Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia. These are bridge countries, as opposed to destination countries (primarily Germany). For the first six months of the period in question, the Route continued into Hungary from Serbia. As the Viktor Mihály Orbán government pioneered militarization of its southern border, the Route adapted to bypass Hungary by turning westward into Croatia and Slovenia.

It is noteworthy that Hungary’s posture towards refugees was initially ubiquitously condemned by the very EU states that followed Orbán’s lead in later months. Some even exceeded Hungary’s egregious border management. As noted below, Europe has not only failed to adapt to the dynamic influx of migrants in this period, but it has made a risky journey riskier and deadlier for refugees.

Map 1. The Balkan Route, pre-March 2016

Source: Eurostat, Frontex.

Process #1: Evolving Population Structure

The refugee wave consisted of an evolving population structure: the migrants themselves changed over time. First, the socioeconomic, gender, and age profile shifted from richer, more educated majorities of military-aged men to poorer, less educated majorities of women, children, and the elderly. Second, the ethnic/national ratios evolved from a wide variety of Arab and African countries to only three source nations: Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. Third, the traveling unit size shifted from single individuals and dyads to groups of five to fifteen migrants.

Socioeconomic Status, Gender, and Age

In the beginning, migrants were primarily younger, military-aged males—disproportionately wealthy, educated, and with greater social capital in Europe. The consensus among refugees and experts alike was that the rich naturally “left first because they could,” and are now drawing their less fortunate relatives. This constituency was the first to flee not only because of their greater resources, but because they were particularly exposed to danger in war-torn areas.

Refugees reported family members in Europe were most often husbands, fathers and brothers who left at the beginning of the wave. Early-stage experts routinely complained of overly-stylish, well-dressed young men taking taxis to Western Unions to withdraw funds. Veteran aid workers expressed resentment toward their “fancy touch-screen phones,” and the fact that “[t]hese guys had more money than any of us.” One volunteer in Greece wondered why “Arabs with their tens of thousands” are welcomed in Europe while he—a poor unemployed engineer, the thought went—would never be allowed into Germany. Another aid worker marveled at how often jacket and blanket donations were thrown away carelessly into the mud on Camp grounds by earlier migrants.

This did not last long. By early 2015, women, children and the elderly became majorities in the migrant flow. Camps were overwhelmed with persons with disabilities or illnesses, elderly people and unaccompanied minors. One doctor compared migrant patients “at the beginning” with his current ones: “most of them now don’t even have that basic education, they are ignorant of basic medical signs.” Drivers were hired for emergency vehicles between refugee hotspots for “high priority cases,” as starvation and deprivation became increasingly prevalent. “They used to be able to pay for taxis,” one ambulance driver recalled, “now we drive them around.” Volunteers noticed their clients was getting poorer and poorer, and that continued movement was increasingly difficult without financial aid. A typical account of the resources and belongings at a refugee’s disposal is:

We lost everything in the war. Our house was bombed. My work was bombed. I had jewelry. It was stolen. Family in Damascus sent me money through a hotel office [bank]. Then the hotel was bombed. We worked in Turkey to survive.

Coinciding with the shift to poorer, less educated populations was a changing gender and age dynamic. At the time of the EU-Turkey deal, 2/3 of the migrants transiting the Route were women, children, and elderly. Military-aged men—an obsession of anti-migrant rhetoric—were unquestionably a minority.

Ethnic/National Origin

The population structure evolved from a wide variety of origin countries to three categories. In September 2015, over fifty source countries were registered, including sub-Saharan African states and nations 5,000 km away from Greece. By January 2016, half were Syrian, 25 percent Iraqi, and 25 percent Afghan. As most of them carried no documents, certifying nationality was difficult. The categorization of economic migrants thus assumed the weight of a racist slur for Syrian

My friend, there is no economic refugee. I left Syria because they will kill me, do you understand, they will kill me, and kill my family. It’s not economic problem, trust me.

As migration volume escalated in 2015, ethnicity/nationality was reified as an identity marker of asylum-seeker status. “True,” “genuine,” “deserving” refugees were selected by their country of origin. Those from “safe countries” were stigmatized as opportunistic imposters: uppity economic migrants with no real grievances. The distinction between economic migrant and refugee was often made in haste by on-site translators, registration officers, or high-level Camp managers.

This policy was not lost on Syrians. A pervasive theme among our subjects was the dichotomy between good and bad migrants. “We” the Syrians were real refugees, “they” the Pashtun/Afghans/Kurds/Iraqis are imposters, shamelessly taking resources reserved for true, moderate immigrants willing to assimilate. “I believe in God,” one subject gazed at a near-by table occupied by a non-Syrian traveling group, “but I am not extreme. They are extreme.”

Traveling Unit Size

The average migrant unit increased dramatically during the wave. Early trailblazers who “pulled” their relatives and friends mostly traveled alone, or in small groups of two or three. In the later phase, migrants traveled in sizable groups of five, ten, fifteen or more. In effect, the unit size changed from dyads and triads of single men to dyads and triads of families, predominantly women and children.

Migration planning changed accordingly. Larger groups typically had a senior male leader. Ostensibly, collective decisions were often made by a senior patriarch. These ranged from minor ones (whether someone should accompany a child to the Camp lavatory, or whether it is acceptable to speak to the translator directly) to life-and-death choices: whether the group should leave someone behind at a checkpoint, where they are headed, and how money should be spent.

This increased size has had mixed effects. On the one hand, the larger units may have brought safety in numbers and expedited processing. Refugees felt safer, pooled resources, and often displayed tremendous solidarity and altruism—including starving for the sake of feeding the rest of the group and relinquishing a life vest to a non-relative child. “We look out for each other,” one subject said, “It’s life or death, and our family help her [traveling companion] family.” Larger traveling units were also thought to be a check on traffickers’ predatory grasp.

But we also documented examples of the opposite of safety in numbers: a diffusion of responsibility that led to vulnerable traveling companions being neglected. Larger groups are slower and more difficult to reroute. As one subject noted, “[My trailblazer] was free to run. He could change paths. He had no reason to wait for anyone.” In contrast, later migrants sometimes sacrificed laggers. After an altercation at the Greek-Macedonian border, one subject lost a traveling companion: “We lost him. There were too many of us. And if we wait no-one gets across the border.” Another recalled: “They left us in Macedonia. We were too slow for them.” Under pressure, even families could turn on each other:

We were all [11] on the same boat. The boss was against it, because we can’t fit. Smuggler says no! And still they said together. They are crazy. I almost drowned because of them. When we almost [sank], I told them – now you [the cousin insisting on unity] should jump in the water. It’s you or everyone drowns. What do you want?

To be sure, themes of unity and altruism were pervasive, but the dangers of sizable migrant groups must not be underestimated—by researchers or policymakers.

Process #2: From Criminal to State Migration

We turn to the second process characterizing the refugee flow: the replacement of criminal mechanisms of migration with state mechanisms. First, transportation shifted from illegal smuggling to government-sponsored transport. Second, the speed of migration accelerated. Third, there was a shift from a moderate-risk but reliable smuggler process to a high-risk and unreliable government process.

Transportation

A migrant entering Europe in the earlier phase of the wave relied on boats and vehicles coordinated and—crucially—operated by smugglers. Taxi drivers, buses, and vans associated with private firms met the black-market demand for illegal crossings. Local newspaper advertisements flaunted the services and prices of quasi-legal travel agencies. Criminal scouts and recruiters patrolled borders, drafting desperate customers. Some trailblazers paid for their own taxis or unregistered drivers. In addition, many walked for tens of kilometers along highways, and crossed borders clandestinely on foot.

Gradually, governments began to replace the illegal service-providers. Cheap state buses, trains and vans soon connected all borders and transit points along the Route. From the Greek islands, migrants traveled almost exclusively using state-organized vehicles. Concurrently, governments engaged in anti-smuggler repression—primarily in the Mediterranean.

Naturally, the smugglers adapted. The deadliest criminal innovation was the use of boats without captains. As government mechanisms took over in Europe, smugglers no longer risked accompanying their clients. A chilling account of the consequences was told by a female subject, a day after her near-death experience:

Smuggler for us was very good. I know this smuggler is working in illegal way, but he help us. They help us. Maybe they took some money, but the problem is that they are afraid. The engine was able to hold only 30 people, and we were 47. The smuggler is a small employee for a big mafia. He is like us. I don’t blame him. You have ten or five smugglers working for the big one. […] When we came to the boat, we were surprised—47 persons. After three hours, the engine stopped working. The engine stopped twice. This is at 1 am. At midnight. No one can see us. We can’t see anyone. We have infants with us. We just have our phones. Maybe we call the smuggler, please, we are going to die. We call 112, 108, I don’t know. One by one. We call the Turkish border soldiers to rescue us. They said, OK, OK but we are close to Greek soldiers more than us. How can I call them? Fortunately, after two hours the motor is moving and the waves move us. Fortunately, [pause] I don’t know how they come. They [Greek coast guard] came and rescue us. [Laughs] And this smuggler is our friend, our friend. He is not responsible. He said, ha ha! This is not my responsibility. My job is to put you on the boat. This is my job. Here, my mission finished. [laughs] If you drown, this is up to Allah.

Note the ambivalent sympathy towards the smuggler who put their lives in jeopardy. This was a recurring theme: refugees largely perceive smugglers as allies, if not saviors. Negative evaluations of smugglers were utterly negligible compared to reports of horrific treatment by lawful agents: guards, policemen, soldiers, and camp workers.

Speed

The average rate of migration accelerated dramatically. In the earlier phase of the wave, the average journey from Turkey to (mid-way) Serbia could take weeks upon weeks (for Afghans and Iraqis, months). In the later phase, the journey was reduced to two-three days. The average length of stay in a given bridge country during the criminal migration phase was 3-5 days; with state-sponsored migration, it shriveled to less than 24 hours.

The smuggler-dominated system was slow for several reasons. First, state repression is best avoided with patience. Trailblazers reportedly stayed for days and weeks in a single safe house—a garage, apartment, remote house, etc.—before the smuggler felt confident enough to attempt a border crossing. One subject reported on her uncle’s residency at a motel for several weeks. He was frustrated and deceived repeatedly about next steps. His smuggler would frequently postpone promised calls, meetings and rides. “They are all paranoid,” she remarks, sometimes avoiding capture by suspending contact with the client. Smugglers also seek to keep clients stationary over prolonged periods to increase their dependency. As one guard put it: “They want to slowly squeeze every last dinar from them before they send them out.”

The state-run migration system could not have been more different. It entailed a series of bridge countries whose camps, border crossings and checkpoints all served a single purpose: to get the migrants off “our” territory as soon as possible, onto the next bridge country. There, they cease to be “our” problem. Thus Greece hurried to dump them onto Macedonia, Macedonia dashed to unload them onto Serbia, etc. – all the way to Germany. Тhe longer the refugees stay within “our” borders, the greater the cost. While criminals wanted to slow the refugees down in order to be their lifeline, the states wanted to speed them up in order not to be their lifeline.

This was aggravated by the uncertainty of sudden border closings and last-minute unilateral moves by neighboring countries. If Route camps had had a common slogan, it would have been: “Keep it moving!” The evident nightmare of volunteers, guards and others tasked with everyday procedures was an announcement by subsequent bridge countries that their borders are closing. This fear was grounded in memories of Hungary’s fence-construction in 2014, and even more in the “catastrophe” of the summer of 2015 when “working at 500% capacity, 26 hours” was still not enough to stop “the swelling.” Any delay was considered unprofessional, if not deadly.

Risk

The transition from criminal to state migration mechanisms increased the risk and cost to life and safety of migration. Rates of death, injury and trauma all multiplied. The increased risk was greatest in the crossing of the Mediterranean; secondarily, in the increased chances of arrest, deportation, and detention in Europe itself. Migrants’ predecessors were much more certain that they would arrive at their destination. They may have been frustrated at the pace, unsure about how exactly they would travel, and cheated by exploitative smugglers. But they were confident they would reach Germany.

With the expansion of the government-regulated camps and transit points, there was a decline of “One Stop Shop” smuggling. Namely, whereas the trailblazers reportedly relied on a single criminal organization, their followers encountered a Route that is inhospitable to this possibility:

- How did you find [the Turkish smuggler]?

- Through word-of-mouth. My friends [who left a year earlier] told me. He was recommended. It was for the full travel, from Turkey to Germany. He had drivers for them [in every country]. […] We thought he would be good.

- But things have changed.

- He didn’t call us for three weeks after we gave him the money! [imitating] Don’t worry, tomorrow. He said in Greece his partner will wait for us, and nothing. Bandits! That’s why today people use six, seven, eight smugglers for the full travel. You need to start again, each contact.

Just as criminal boat captains no longer piloted, a crackdown on smugglers led to increased risk in this domain as well. Each new border-crossing required refugees to search for new smugglers, exposing them to what they had already endured in Turkey: danger, uncertainty and disappointment.

Chart 1. Summary of Process 1 (the people) and Process 2 (the journey)

Preparing for Future Waves

The popular marker “European migration crisis” is misleading in its Eurocentrism. The share of migrants entering Europe was negligible compared to those entering Turkey (>2.3 million refugees by 2016), Jordan (>600,000) and Lebanon (>1.1 million, constituting ¼ of the national population). The crisis is in fact a Middle Eastern one, with a modest subset of the overall migrant population spilling over into Europe.

What is unique, however, is the refugee wave itself – its evolving dynamic, composition, and direction. Future refugee waves will be generated not only by war, but by global warming– and they are likely to have dynamics akin to the ones delineated above. As an NGO slogan rightly pointed out about the European refugee panic: “This is the new normal.” Learning from the Balkan Route can help us prepare and react effectively to future reprises.

Danilo Mandić is a College Fellow in the Department of Sociology at Harvard University. His research focuses on social movements, nationalism, ethnic relations, civil war and organized crime. He is also co-editing a volume on youth in Southeast Europe, and collaborating with BCARS at Northeastern on a study of Syrian refugees on the Balkan Route.

Photo: Roeszke, Hungary. Spectral-Design | Shutterstock

References

Albahari, M. Crimes of Peace: Mediterranean Migrations at the World’s Deadliest Border, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. 2015.

Amnesty International. Catastrophic Moral Failure as Rich Countries Leave bills of Refugees to Cruel and Uncertain Fates, AI Press Release, London. 2015.

Bauer, W. Crossing the Sea with Syrians on the Exodus to Europe, CA: & Other Stories, Los Angeles. 2016.

Carrera, S., et al. Irregular Migration, Trafficking and Smuggling of Human Beings: Policy Dilemmas in the EU, CEPS Paperback, Brussels. 2016.

Collett, E. The Paradox of the EU-Turkey Refugee Deal, Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. 2016.

Costello, C. “It need not be like this”, Forced Migration Review, 51: 12-14. 2016.

European Council on Refugees and Exiles. Wrong counts and closing doors: The reception of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe, Asylum Information Database. 2016.

Fargues, P. and Bonfanti, S. When the best option is a leaky boat: why migrants risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean and what Europe is doing about it, European University Institute, Florence. 2014.

Gillespie, M., et al. Mapping Refugee Media Journeys: Smartphones and Social Media Networks, The Open University / France Médias Monde. 2016.

Heller, C. and Pezzani, L. Ebbing and Flowing: The EU’s Shifting Practices of (Non-) Assistance and Bordering in a Time of Crisis, Zone Books, New York. 2016.

International Labour Organization. ILO global estimate of forced labour: results and methodology, International Labour Office, Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour (SAP-FL), Geneva. 2012.

International Organization For Migration. Migration trends Across the Mediterranian: Connecting the Dots, ION Middle East and North Africa Regional Office, Cairo. 2015.

International Organization For Migration. Fatal Journeys Volume 2. Identification and Tracing of Dead and Missing Migrants, IOM, Geneva. 2016.

Kyle, D. and Koslowski, R. Global Human Smuggling: Comparative Perspectives, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 2013.

Liempt, I. and Sersli, S. “State responses and migrant experiences with human smuggling: A reality check”, Antipode, 45(4): 1029-1046. 2013.

Neske, M. “Human Smuggling to and through Germany”, International Migration, 44(4): 121–163. 2006.

Palloni, A., et al. “Social Capital and International Migration: A Test Using Information on Family Networks”, American Journal of Sociology, 106(5): 1262-1298. 2001.

Paszkiewicz, N. “The danger of conflating migrant smuggling with human trafficking”, Middle East Eye, 2 June 2015.

Rais, M. “European Union readmission agreements”, Forced Migration Review, 51: 45-46. 2016.

Shelley, Louise I. Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective, Cambridge University Press, New York. 2010.

Sulaiman-Hill, C. M. R., et al. “Changing Images of Refugees: A Comparative Analysis of Australian and New Zealand Print Media 1998−2008”, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 9(4): 345-366. 2011.

Triandafyllidou, A. and Maroukis, T. Migrant Smuggling. Irregular Migration from Asia and Africa to Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. 2012.

Ventrella, M. “The impact of Operation Sophia on the exercise of criminal jurisdiction against migrant smugglers and human traffickers”, Questions of International Law, 30: 3-18. 2016.

Published on January 5, 2017.