This is part of our feature Transformation of Higher Education and Research in Europe.

Higher education is very popular today. The population share with exposure to college has steeply risen across the world, particularly in Europe. For instance, between 1995 and 2011, the graduation rate for academic bachelor’s degrees has increased from 33 to 39 percent per cohort in the United States. In Germany, it has grown from 14 to 31 percent; and in Norway, it has increased from 26 to 43 percent.[1]

Policymakers have also focused their attention on the sector. Hailing education as “the best anti-poverty program,” US President Barack Obama has called on the country to re-attain the “highest proportion of college graduates” worldwide. Similarly, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has declared her resolve to build an “education republic,” given that “intelligent brains” are the country’s “most important resource.”

Economists contend that the expansion of higher education can improve both social inclusion and economic performance in the contemporary context of globalized and knowledge-based competition. Politicians have followed their advisors’ recommendations and reconceived the role of education in terms of social investment. They now view university-based learning as a means to empower individuals to make the most of their life chances and adapt to changing socio-economic circumstances over their life courses.

Having outgrown the ivory tower, higher education has moved to the center of societies’ efforts to sustain economic growth and provide social security. This rise to prominence has also turned the sector into a key battleground for social conflict.

Having outgrown the ivory tower, higher education has moved to the center of societies’ efforts to sustain economic growth and provide social security. This rise to prominence has also turned the sector into a key battleground for social conflict. Yet, so far, scholarship has had little to say about the politics of university systems’ institutional transformation—i.e. the distributional struggles that determine “who gets what, when and how” (as American political scientist Harold Laswell once famously defined “politics”).

Specialists in European studies have much to contribute to redressing this imbalance between empirical transformation and scholarly silence, by tapping into the repertoire of analytic tools that they have already productively used for illuminating other areas of modern societies’ recent structural evolution. In turn, it is high time for scholars to intervene in the debate on higher education’s contemporary shifts in three ways. First, researchers can help define the contextual conditions that frame intensifying social conflict in the sector; second, they can improve the conceptualization of recent institutional changes in higher education; and third, they can contribute to uncovering the complex causal dynamics that link the evolving context with shifting institutional and social outcomes. Let me elaborate each point to put down a few markers that could help guide this path.[2]

*

Without being derivative, the politics of higher education are strongly bound by the structural forces acting upon the sector. Among the most important constraints, is the widely perceived need to better target public spending in higher education. While higher education continues to comprise only a small share of welfare states’ expenditures (usually between 1 and 2 percent of GDP depending on the country), overall outlays for higher education have increased as the sector expanded. Moreover, fiscal demands have also grown in other areas of the welfare state, including in old-age care, childcare, and basic social assistance. Given political limits to increasing tax loads and shifting public into private spending, pressures have been rising to keep expenditures on universities under control.

Given higher education’s nature as a personal service, productivity increases in the sector have been lower than in areas of the economy that could more heavily rely on capital substitution and automation.

Within higher education, however, this goal has run up against Baumol’s cost disease: Given higher education’s nature as a personal service, productivity increases in the sector have been lower than in areas of the economy that could more heavily rely on capital substitution and automation. Differentials in productivity increases have in turn, over time, driven up higher education’s cost base relative to sectors such as manufacturing. Moreover, for many universities, the degree of global competition has strongly increased, pushing up salaries for “star” faculty and fueling pressures to invest in higher-standard student services.

Sector-specific pressures have coincided with welfare states’ broader reorientation toward the notion—though not necessarily the reality—of providing equality of opportunity rather than supporting the goal of equal social outcomes. Increasingly geared to providing what Wolfgang Streeck has termed “competitive solidarity,” welfare states have moved to support citizens behaving as entrepreneurs of their own human capital.

This has left the academy at the heart of what Stephan Lessenich has called the “transformation of the social”: Policymakers have taken steps to redefine societies’ relationships to their citizen members—in line with John F. Kennedy’s famous call that citizens should not ask what the country could do for them, but instead wonder what each individual could do for the country. De-emphasizing citizens’ rights (i.e., a collectivity’s duties vis-à-vis its citizens), policies have come to stress citizens’ duties for the collectivity’s destiny—including by living up to their responsibility to make use of education in order to continually update their human capital.

*

The comparative analysis of changes in higher education requires the definition of theoretical categories to assess individual outcomes. Here, scholarship on institutional liberalization could guide research on higher education’s transformation. Similar to societies’ political economies more broadly, countries’ higher education systems have undergone processes of institutional change that have increased the scope for competition-based allocation of resources to encourage entrepreneurialism and accountability. In higher education, this transformation has been state-sanctioned, and involved the strengthening of market principles—self-reliance, rivalry, and decentralized decision-making—in university governance. Seeking to turn universities into strategic actors, policymakers across countries have cut unconditional public funding per student to increase self-reliance, launched competition policies to ensure rivalry, and expanded universities’ autonomy to enable decentralized decision-making.

While the modes and results of this transformation have differed across countries, all higher education systems have arguably morphed into varieties of what Sheila Slaughter and her collaborators have called “academic capitalism,” i.e., a new accumulation regime in higher education. As reformers have sharpened incentives for organizational (and individual) entrepreneurship, reforms have tended to weaken checks on capitalist rule by undermining the power and collective identities of both academic professionals and student populations. Like societies more broadly, increased competition in today’s mass-access higher education systems has reduced self-governance, rule-bound administration, and student mobilization that could act as counterweights to the upward redistribution of positional capital.

*

Getting the politics of transformation straight is an exercise in tracing causal mechanisms. While one research project could never get the whole story, a set of studies should surely be able to uncover crucial parts of the conjunctural patterns of causation that are typical for the social world. In the process, scholars could take cues from research on differential policy feedback in distinct welfare regimes—each with inherited arrangements between the state, market, and the family, and famously theorized by Gøsta Esping-Andersen. Moreover, they could be inspired by research that has demonstrated the effect of contrasting state structures, such as Ellen Immergut’s important study on the consequences of veto points. Finally, they could seek to define the coalitional dynamics in line with Kathleen Thelen’s power distribution perspective on group politics.

Much research—both empirical and theoretical—remains to be done. It will be exciting to see scholarship catch up with empirical developments. If all goes well, scholars might even be able to contribute to improving the quality of policymaking.

Tobias Schulze-Cleven is a political scientist and assistant professor at the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University.

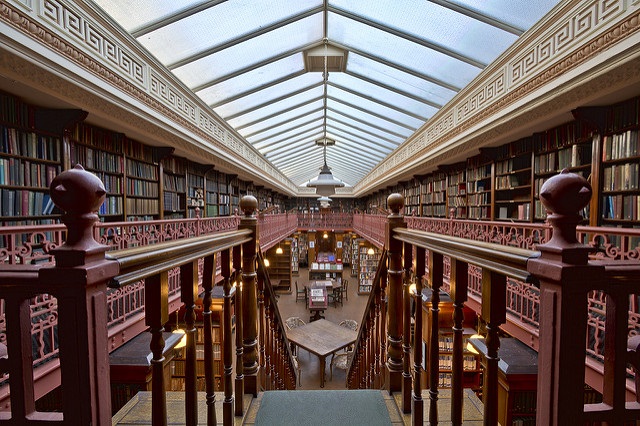

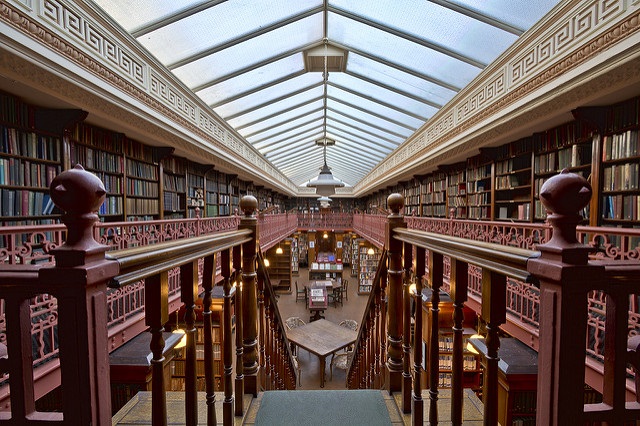

Photo: The Leeds Library | Michael D Beckwith | Flickr

References:

[1] OECD, Education at a Glance 2013 (Paris: OECD, 2013), 56-58.

[2] For more on these points, see Tobias Schulze-Cleven, “Liberalizing the Academy: The Transformation of Higher Education in the Unites States and Germany.” CSHE Research & Occasional Paper 1.15 (Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education, 2015)

Published on December 1, 2016.