Translated from the Italian by André Naffis-Sahely

Simulation is the keyword that runs throughout this extraordinary cultural transformation. It includes several levels of virtual reality and various methods of reproducing monuments or historic cities: you can replicate Venice “in the flesh” inside a Las Vegas casino or a neighborhood in Istanbul, but you can also situate it inside a virtual city which anyone can explore via their avatars from the solitude of their own home.

We cannot reduce this shift to an ephemeral fashion trend, or consider it a tribute to our dominant technologies and market mechanisms. Another factor is at least as important: the need to explore notions of diversity, which has been prompted by the global widening of our horizons. As University of California at Berkeley architectural professor Nezar AlSayyad argued, the need to “find authenticity and truth in times and places away from his/her own everyday life” has been answered in part by mass tourism, whose unexpected metamorphosis conferred the obsolete practices developed during the era of the Grand Tour to countless multitudes of petits touristes. That slow kind of traveling, once the exclusive preserve of learned elites—and which was thus inspired and nurtured by a great deal of reading, or accompanying tutors and guides and the production of countless diaries and water-colors—has been shattered by the impalpable rhythm of mass tourism. Nevertheless, the direct experience of urban space, accommodation, and ways of living that are not one’s own, has remained an essential component of travel, even though the current practice of hit-and-run visits often elicits meager results (75 percent of those who visit Venice stay there only for a day). Souvenir snapshots—where quantity trumps quality—are a testament to the tourists’ ritualistic presence, and not their cultural curiosity. Photographs do not preserve a memory; instead they have replaced our remembrance and our ability to see.

The fake Venices of Las Vegas, Dubai, and Chongqing are even more paltry responses to that need for diversity and otherness, which can find a second-rate outlet in both forged and virtual realities. Yet the pervasive manner in which virtual reality has gained the upper hand and blurred the line between the fake and the authentic while simultaneously subverting its terms amounts to this: virtual reality can be better than normal reality not only because it is more immediately accessible, but because it elicits more standardized (and therefore more marketable) emotions. Instead of introducing something real, virtual reality can simply take its place; physical reproductions found in theme parks—or pseudo-historical neighborhoods, those open-air museums that re-create a fake German or Norwegian village using authentic building materials—can do this in an even greater capacity.

In his Repairing the American Metropolis: Common Place Revisited, urban planning and architecture professor Douglas Kelbaugh quotes a college graduate just back from her first trip to Europe:

I didn’t like Europe as much as I liked Disney World. At Disney World all the countries are much closer together, and they show you just the best of each country. Europe is boring. People talk strange languages and things are dirty. Sometimes you don’t see anything interesting in Europe for days, but at Disney World something different happens all the time and people are happy. It’s much more fun. It’s well designed.

It’s hard to believe that someone actually mouthed such embarrassing words, but the logic they employ is certainly authentic: what is different is boring, and what is identical (to ourselves) is reassuring, and thus it makes us happy. It would be useless to laugh this off, since the Disneyfication of our cities proceeds unabated day by day, and with it the tacit stripping of their variety, diversity, and identity, a process whereby history is reduced to a mere brand. Even in Venice. In fact, especially in Venice. According to several observers—and I’m going to quote only from an article called “The Ugly Side of Venice,” which appeared on the Gourmantic website—the real Venice is becoming less welcoming than its knockoffs:

Ugly monstrosities in the form of massive advertisements covered the iconic buildings… Ponte dei Sospiri was barely visible, dwarfed by fake skies and make belief [sic] clouds. Further along, Piazza San Marco was under the effects of Acqua Alta. But this inconvenient yet natural phenomenon paled in comparison to the giant Trussardi advertisement towering above the square… Granted, many of Venice’s buildings are in a state of disrepair and require sizable funding for restoration. But hiding the beauty of the city with ugliness should come with a travel warning. Don’t come here… La Serenissima is no longer serene. The city itself is no longer a pleasure to be in… I didn’t raise an eyebrow at the multilingual signs on rubbish bins forbidding tourists from littering, loitering, eating and drinking in Piazza San Marco.

Comparing Venice to Disneyland has now become commonplace; without citing too many examples, simply two will suffice. In 1981, the Italian journal Urbanistica published an article which argued, among other things, that “the transformation of Venice into Disneyland could very well signal the transition to a more creative and cheerful way of life.” The author in question was a professor of urban planning, had edited Urbanistica for seven years, and was subsequently a member of Italy’s Higher Council for Cultural Heritage and Landscape. The second example is culled from an advertisement posted on the Internet in February 2014:

Veniceland, the Disneyland of the Lagoon, is coming to Italy. On the island of Sacca San Biagio, the roller-coaster giant Zamperla will build a theme park dedicated to the history and culture of the city, in order to remind visitors of a time when Venice was an international economic powerhouse.

The island this article refers to is situated in the Giudecca Canal, only a step away from the Venice we know and love: yet if one wishes to speak about La Serenissima’s history, the city itself isn’t enough any more. Instead, one needs a Venice equipped with “educational areas set aside for schools, huge touch-screen displays, performances developed in partnership with the city authorities, a specific area dedicated to the splendid carnival, roller coasters, slides and a large Ferris wheel.”

Reproductions of various natural landscapes (the barene, or salt marshes) and historical reenactments (the Battle of Lepanto) have been planned, all of which has been granted the seal of approval by the University of Venice, whose rector “offered his university’s expertise to the company so that the protection of the city’s historical and environmental treasures would be guaranteed. Nobody would think of calling such a place a Luna Park.”

Thus, The Guardian newspaper was certainly correct when it published a provocative piece in June 2006 entitled “Send for Disney to Save Venice,” which argued that if Venice’s future lies in cheap, mass-market tourism, then it might as well be entrusted to the Disney Corporation, who would run it better than the city authorities.

No one is safe from such a radical drift. In Pompeii, city authorities are planning a Pompeii Experimental Park, a sort of facsimile of the actual archaeological site, which one can only presume is now deemed too boring. Yet there’s nothing new about this idea: back in April 2007, then Minister of Culture Walter Veltroni launched the idea of a Jurassic Pompeii, “made up of gadgets, CDs, recreational areas and virtual games, and created to salvage the deteriorating site of Pompeii, which belongs to our archaeological heritage.” All of this would be accomplished in a hurry, of course: according to the minister, it would take only “three years and a special law.” Not to mention what Gianni Alemanno cooked up in 2008 when he was mayor of the Italian capital in order to “save Rome from a decline in tourist numbers,” namely: “the Disneyland of ancient Rome, featuring virtual reconstructions that will allow visitors to watch shows at the Colosseum, chariot races at the Circus Maximus, explore the catacombs, or take a dip in the Baths of Caracalla.”

Even in their most depraved form—for instance, Veniceland—these new coinages and cultural initiatives are seen by some as a democratization of culture, and anyone who dares question them is deemed elitist. Historian Howard Kaminsky has written that in a mass society our attempts to analyze history have fundamentally changed:

In resonance with the post-national and post-political mentalities of a mass society, its function is not to impose a new, authoritative story but rather to stock the scholarly section of what can be imagined as a Universal Historical Museum, corresponding to the needs of our time much as do supermarkets, shopping malls, the Internet, multichannel television, and the various post-modern deconstructions of traditional modernity… Disney World [is]… both epitome and major mover of this postmodern drive to reduce our culture from a meaningfully structured system to a decontextualized wilderness of repackaged symbolic forms in no particular order, all to be consumed indiscriminately as commodities… [This] is obviously in line with this Zeitgeist, which is a point against it only if one thinks ignoring the Zeitgeist will make it go away.

From this perspective, according to the neoliberal mindset now glorified as our zeitgeist, consenting to the commodification of the entire planet and wandering around the cultural artifacts of our past with a shopping cart and credit card are facets of a categorical modernity deemed as inexorable as the passage of time.

This brutal variety of presentism presumes that our era can, and should, be guided solely by a market mentality: and that the crowds which throng our shopping malls are the only possible expression of postmodernity and the apex of its rituals and values, the only measure by which one is allowed to shape both the present and future. Yet why do those who idolize the free market economy place all bets on a single zeitgeist that allows for no alternatives? Why must our mass culture obsess over the repetition of sameness and not further our knowledge of diversity and otherness? Whatever triggered the race to build theme parks and fake residential Venices replete with Rialto Bridges wasn’t the democratization of culture, but rather the imposition of a standardized and sterilized version of our past and our diversity. This has nothing to do with the blissful coexistence of multitudes, but is actually the same old habit espoused by the privileged classes who wish to keep the pleasures of what is authentic all to themselves, while offering pale imitations to the masses, paternalistically camouflaging them as gifts. These practices reveal no interest in what is different except from the desire to absorb it, commercialize it, and finally neuter it so that it no longer represents an alternative to the dominant monoculture. History sells has been said over and over again, so long as it is attractively packaged of course. So long as it is literally consumed.

The very act of selecting a few iconic monuments in order to promote them as the authentic epitome of Venice (nevertheless built on a reduced scale and employing low-quality materials) lays bare the authoritarian mechanism that presides over these “democratic” practices. There are those who decide which objects are conventional and representational enough to summarize Venice—and then there are those who have to abide by those decisions, or better yet, those who are persuaded to pay for them. This arbitrary selectiveness toward the continuum of art and history has erected a powerful filter that eliminates any notion of complexity and distorts the whole. This filter refuses to recognize diversity, which is the yeast of history and our cultural memory, but instead forcibly annexes what is different to the monolith of the identical. It subordinates what is true to what is false, what is complex to what is simple, the eternal to the ephemeral. It puts on a show of cultural diversity driven by the single aim of a means of virtual simulation, to then sell it, adulterating it in the process. Yet the simulation and the simulacrum are only a step apart. As cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard wrote: “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth—it is truth that hides the fact that there is none. The simulacrum is the only truth.”

*

That such a mechanism of cultural manipulation came into play by cloning Venice from afar (in China and the United States) is now beyond question and will undoubtedly keep occurring. Yet what effects has this had on Venice itself? One would be forgiven for thinking that each new clone would enrich the glory of that city on the Lagoon and its amazing diversity, but this is not the case. The virus of the simulation has wormed its way into Venice and has ensnared it, just like a mirror that swallows up the face of whoever looks into it. Or better yet, like a burning glass that doesn’t merely collect light and refract it, but instead concentrates its rays onto a small area to combust and destroy. While Venice’s inhabitants continue to flee, thereby depleting the city’s civic consciousness and cultural memory, the Ugly Side of Venice is taking over and entrenching itself, allowing the unthinkable to happen: a fake Venice next to the real one, whereby the truth of the simulacrum shatters and engulfs the truth of history. The planned project of building a Veniceland right next to Giudecca is particularly heinous precisely because it suggests situating the copy right in front of the original; in fact, it actually suggests putting the two in direct competition with each other, thus decreasing the city’s ability to tell its own story: by embodying it, and not just mimicking it, to tell a story that is made of stone, and not papier-mâché, that is expansive and not reductive, that is real, and not fictional. Veniceland and its siblings resemble shopping malls, yet this similarity implies that everything has a price, and that anything that can’t be sold on the market has no value whatsoever. Indeed, it presupposes that a fake Venice can be more valuable than the real one specifically because it can be marketed and advertised. Yet this specific project is a telltale clue that Venice is losing its own identity, and is trying to find it elsewhere, at an exorbitant price. It’s as if this city of such miraculous beauty were becoming invisible to the very people who live in it, or as though its identity were growing weaker with each passing day. Like an old man on his deathbed.

Venice multiplies itself and refracts, like light bounces off the shards of a mirror that has broken into a thousand pieces. Yet in this unprecedented scenario, the city runs the risk of losing its very soul and life force. Instead of validating its uniqueness and indivisibility, it risks slipping into a dizzying confusion of facsimiles. Instead of distilling its resources, ideas, and creativity into the fabric of city life, it risks losing itself in a delirium of imitations. Instead of strengthening its inhabitants’ civic awareness and cultural memory, it confuses elitism with history and popular culture with its own destruction. Yet neither democracy nor policy lies on the horizon, and without a population the city cannot be said to have any citizens. The only thing that will remain is a skeletal, monotonous zeitgeist, a kind of commodities exchange or souk where anything that isn’t sold dissolves into nothingness. One can certainly replicate Venice, that’s true; one can even pretend to do so in the name of diversity. Yet Venice enjoys an advantage over all its imitations and simulacra: it doesn’t pretend to be diverse, it simply is diverse.

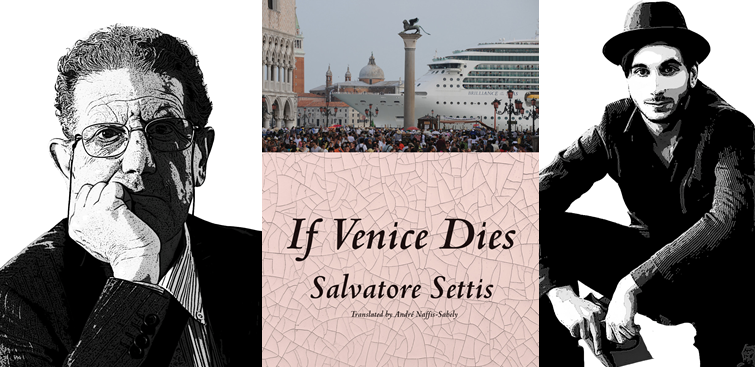

Salvatore Settis is an archaeologist and art historian who has been the director of the Getty Research Institute of Los Angeles and the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa. He is chairman of the Louvre Museum’s Scientific Council. Settis, considered the conscience of Italy for his role in spotlighting neglect of its national cultural heritage, has been mentioned frequently for the post of minister of culture and Italian president. He is the author of several books on art history as well as a regular contributor to major Italian newspapers and magazines.

André Naffis-Sahely is a translator and poet. He was born in Venice and grew up in Abu Dhabi.

This excerpt from If Venice Dies is published by permission of New Vessel Press. Copyright © 2015 Salvatore Settis. Translation copyright © 2016 André Naffis-Sahely.

Photo: Salvatore Settis, New Vessel Press

Photo: André Naffis-Sahely, Able Muse

Published on November 1, 2016.