Trade in Green Hydrogen Needs More Than Goodwill: Reflections on Angola’s Hydrogen Deal and the EU-Angola’s SIFA Agreement

European Commission. 2023. EU and Angola sign first-ever Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement. Newsroom, DG Trade. 23 November. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/

By Rozenn Heim

The EU and Angola have committed to fostering more transparent and sustainable investment through SIFA. Still, in emerging sectors like green hydrogen, SIFA alone may not be enough to make investment both viable and lasting.

Faced with climate urgency, the European Union (EU) is striving to decarbonize its economy by 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement [1] and the European Green Deal. [2] Green hydrogen [3] has emerged as a key energy alternative. Nevertheless, the production of green hydrogen domestically remains economically non-viable, due to the high cost of hydrogen electrolysis equipment, expensive land for installations, and high labour costs in Europe.[4]

As a result, the EU is turning to more affordable green hydrogen producers worldwide, including Angola. But this strategy raises concerns. Critics warn of a return to extractive trade patterns, where raw materials leave the producing country while most of the profits remain in Europe. In this model, no local industrial value chain develops,[5] leaving the economy tied to volatile export markets, with few alternatives when prices fall or demand shifts. In the context of green energy, this model has been referred many times as ‘ecological colonialism,’ or ‘energy colonialism.’ [6] Political scientist Franziska Müller uses this term to show how green energy transitions can recreate global inequalities rooted in postcolonial practices. [7] In other words, wealthier countries extract resources and profits from economically vulnerable producer countries, while local communities face environmental degradation and receive little economic benefit.

Turning the page on unfair investment practices – SIFA and the attempt to reshape EU-Africa relations

To prevent exploitative investment practices and promote fairer partnerships, a new legal framework entered into force on 1 September 2024: the EU–Angola Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement (SIFA).[8] Recognised as the first of its kind, SIFA promotes sustainable and transparent investments while also protecting Angola’s sovereign right to regulate.

In this view, SIFA is designed to benefit both sides. For Angola, SIFA serves to attract responsible international investors and move the economy beyond traditional industrial sectors, like oil and diamonds. For the EU, on the other hand, it provides a legal framework that reassures businesses by providing transparency, simplifying procedures, and centralising key information. This means investors can connect more easily with Angolan partners in their target industries and operate in a more predictable environment.

From ISDS to SSDS

One of SIFA’s most significant innovations is its replacement of the controversial Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) with a State-to-State Dispute Settlement (SSDS), thereby safeguarding Angola’s sovereign right to introduce new regulations. Understanding why this matters requires looking at why the ISDS became so controversial.

ISDS allows foreign investors to bypass domestic courts and bring host states directly before private international arbitration tribunals of their choosing. These tribunals operate outside national jurisdictions and give companies a powerful tool to challenge new laws or policies that may affect their profits. Critics argue that this system favours corporate interests over the public good, as companies can use it to pressure governments into avoiding or reversing new regulations.[9] A striking example is the Vattenfall v. Germany case, where the Swedish company sued for €4.7 billion after Germany announced its nuclear phaseout. Such cases have hung like a Damoclean sword over governments, discouraging them from adopting new regulations.

SSDS removes that ‘sword’: disputes are now settled between states rather than through direct claims by private companies. Consequently, SSDS is a key provision in SIFA that safeguards the host state’s regulatory autonomy while still providing a structured, state-to-state mechanism for resolving conflicts.

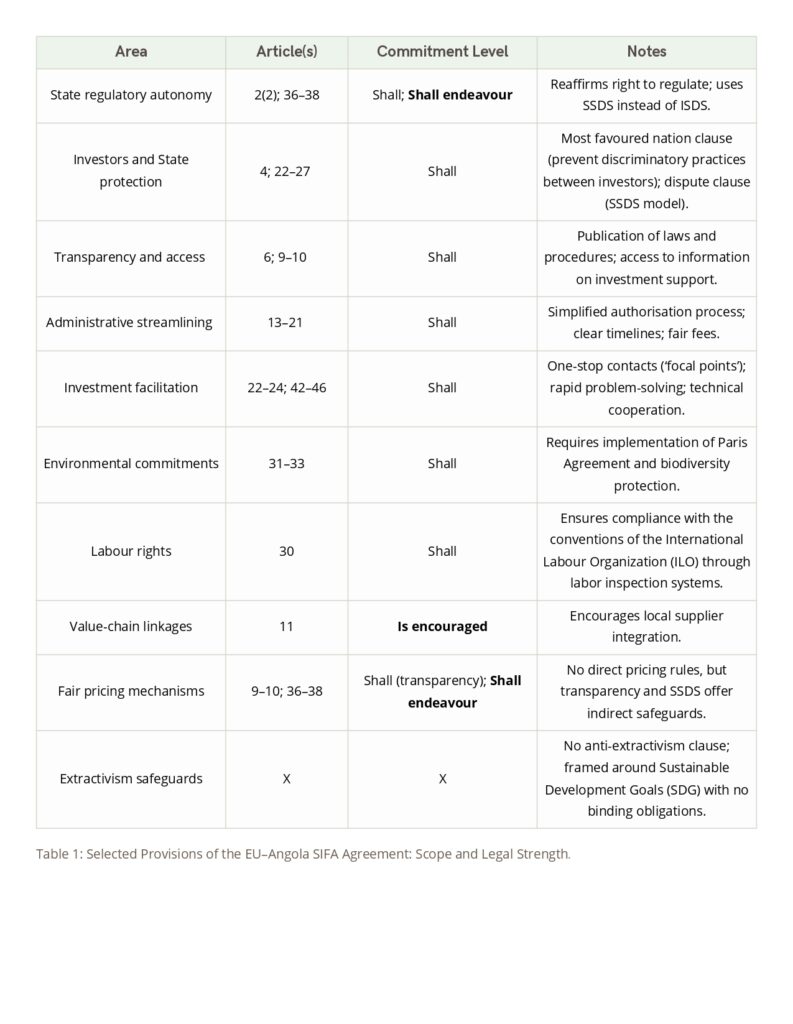

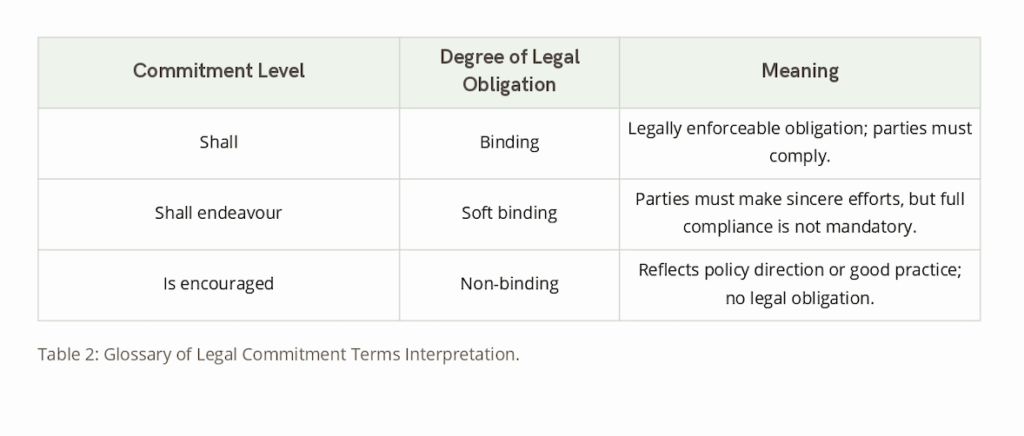

In the meantime, the EU-Angola agreement promotes transparent and sustainable business practices. Core commitments of SIFA include environmental protections, labour rights, and transparency on trade regulations. However, enforcement varies. For instance, SIFA encourages the creation of local value chains [10]— but this remains a non-binding provision. Meanwhile, investors understandably seek to secure profits. Finding a balance that satisfies both sides remains a delicate task.

The Barra do Dande Green Hydrogen Deal

Angola faced a harsh financial crisis from 2015 to 2020 due to over-reliance on oil, with profits fluctuating sharply. In response, the government sought to diversify its economy by investing in renewable infrastructure, including the dam in Barra do Dande. Yet much of its energy generation capacity remained untapped until foreign investors saw the opportunity in hydrogen conversions.

In 2021, German firm GAUFF Engineering [11] and Angola’s Sonangol [12] began developing a green hydrogen project to export surplus electricity to Europe. In October 2024, Conjuncta GmbH [13] and CWP Global [14] joined the consortium for the deal. [15]

Their blueprint focuses on building local value chains around hydrogen derivatives and supporting the creation of skilled jobs for Angolans. While the project aligns with SIFA’s objectives, it does not rely on the SIFA framework. Why not? First, negotiations for the deal predated SIFA. Second, GAUFF had strong local contacts and backing from the H₂-Diplo network – a German-led hydrogen diplomacy initiative. Its network fostered dialogue on hydrogen and connected the three private firms with Sonangol. Key figures involved in the project had worked closely with the Angolan government for many years. This long-standing familiarity with the local environment gave them a clear advantage.

In comparison, SIFA is designed for firms unfamiliar with Angola. Lastly, this private initiative, led by German stakeholders, identified a clear market potential without EU intervention: the Barra do Dande dam’s energy surplus. There is no official information, but the Green Hydrogen Deal likely relies on contractual tools such as Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). A PPA is a long-term contract that secures pricing between an energy producer and a buyer, therefore ensuring income for the host state and reliable delivery for investors. However, PPAs are often criticised for lacking transparency and traceability in their price-adjustment formulas. [16] This raises concerns about the absence of oversight on balanced and transparent pricing mechanisms. Indeed, striking a pricing balance that ensures fair returns for Angola while keeping projects profitable for investors is essential to ensure economic fairness and long-term viability.

Would the Barra do Dande project have been any different under SIFA?

Well, probably – at least in terms of transparency and administrative safeguards. The agreement requires Angola to publish clear information on investment laws, procedures, and incentives (Articles 9 and 10 – summary table at the end of the article). In addition, it ensures that administrative decisions, such as licensing or permits, are impartial and objective (Article 6). In case of non-compliance, the EU and Angola would have been able to trigger the SSDS mechanism. Finally, these provisions would have helped reduce uncertainties for new investors unfamiliar with Angola’s regulatory landscape.

The Green Hydrogen Deal at Barra do Dande operates outside the SIFA framework, meaning it is not bound by the agreement’s pricing and transparency provisions. Still, it broadly aligns with SIFA’s value-chain goals, as well as its labour and environmental provisions. Importantly, even if the project had been covered by SIFA, the agreement would not have regulated pricing formulas or enforce a specific ‘fair price’ clause, such as PPAs mechanisms. Articles 18 to 21, the ‘fees’ chapter, lay out three core principles: authorisation fees must be reasonable and transparent, procedures impartial and accessible, and relevant information published clearly and on time. [17] Overall, these rules focus on transparency and non-discrimination. However, they stop short of defining what constitutes a ‘fair price’ when prices or currencies shift over time. As a result, they offer only partial safeguards and lack mechanisms to ensure balanced pricing in long-term energy contracts.

In practice, PPAs would have remained private instruments, negotiated and managed solely by the companies involved — and therefore outside SIFA’s direct control. Importantly, price setting has never been part of SIFA’s mandate, even though this limitation matters in sectors where pricing stability is crucial for long-term investment, such as green hydrogen.

Beyond SIFA: why Angola needs strong national laws

An interview with a stakeholder revealed a key issue: [18] the absence of hydrogen-specific legislation in Angola. While SIFA provides a framework for facilitation, it cannot substitute for detailed national laws. Without clearer regulatory rules on hydrogen and other key sectors in need of foreign investment, investors may remain hesitant to engage in Angola.

Indeed, European investors generally appear to lack a clear understanding of Angola’s market landscape and the potential of emerging sectors. Although SIFA offers a transparent framework and promotes sustainable investment principles, it requires proactive communication and strong efforts to connect Angolan to European stakeholders. To bridge this gap, clearer promotion of SIFA and sector specific information are essential. Only then can mindful investment be aligned with Angola’s development priorities and long-term interests.

Key Takeaways

SIFA marks a shift in the EU’s investment policy and offers a valuable base for investors, especially those unfamiliar with Angola. It aims to improve communication channels, link stakeholders, and clarify procedures. However, its impact will depend on the effectiveness of its communication about opportunities, stronger connections between stakeholders, and a genuine willingness on the part of European investors to engage with SIFA. The Green Hydrogen project shows that valuable private partnerships are possible without SIFA, but it also highlights the shortcomings when local legal frameworks for sector-specific industries are weak, especially in ensuring effective oversight and price transparency.

To avoid a new form of ‘ecological colonialism’, the EU and its partners must go beyond facilitation. Concretely, this means engaging in constructive dialogue to promote sector-specific legal frameworks that provide clear, predictable rules for emerging industries such as green hydrogen.

By combining SIFA’s facilitating role with robust national regulatory frameworks, green hydrogen trade can become both safer for European investors and fairer to the Angolan population. Only then will the EU be able to deliver on its promise of a fair and sustainable energy transition, and Angola be able to reap real long-term benefits.

Table 1 [19]

References

[1] European Parliament. 2019. EU and the Paris Agreement: Towards Climate Neutrality. Last updated December 7, 2023. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20191115STO66603/eu-and-the-paris-agreement-towards-climate-neutrality.

[2] European Commission. 2021. Delivering the European Green Deal. July 14, 2021. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en.

[3] Hydrogen is considered green when produced using renewable energy sources.

[4] Fortin, Frédéric. 2025. “La filière de l’hydrogène vert en proie aux doutes.” Banque des Territoires, 26 mars 2025. https://www.banquedesterritoires.fr/lhydrogene-vert-dans-le-rouge; Oliva, Sebastian, and Matias Garcia. 2023. “Investigating the Impact of Variable Energy Prices and Renewable Generation on the Annualized Cost of Hydrogen.” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 48 (37):,13764-13765.

[5] A value chain is the sequence of activities and processes involved in creating a product or service. At each stage, value is added before it reaches the final customer.

[6] Müller, Franziska. 2024. “Energy Colonialism.” Journal of Political Ecology 31 (1): 701–717.

[7] Müller, Franziska, Ayşe Çalışkan, David Kaldewey, Swenja Surborg, and Carolin Wendt. 2022. “Hydrogen Justice.” Environmental Research Letters 17 (11): 115006.

[8] European Union and Republic of Angola. 2024. Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Angola. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202400830.

[9] Nathalie Bernasconi-Osterwalder and Rhea Tamara Hoffmann, The German Nuclear Phase-Out Put to the Test in International Investment Arbitration? Background to the New Dispute Vattenfall v. Germany (Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2012), 11–12.;

Gary Clyde Hufbauer, “Investor-State Dispute Settlement,” in Trans-Pacific Partnership: An Assessment, vol. 104, ed. Cathleen Cimino-Isaacs and Jeffrey J. Schott (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2016), 203–5.

[10] European Union and Republic of Angola 2024, art. 11, 16.

[11] GAUFF Engineering is a German engineering firm specializing in global infrastructure projects in water, energy, and transport.

[12] Angola’s state-owned oil and gas company, created in 1976.

[13] Conjuncta GmbH is a German project development and investment firm active in energy, infrastructure, and green hydrogen.

[14] CWP Global is an international renewable energy developer from Australia, focusing on wind, solar, and large-scale green hydrogen projects.

[15] Costa, Tatiana. 2024. “Sonangol Signs Agreement to Develop Green Hydrogen Project in Barra Do Dande.” VerAngola, October 4. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.verangola.net/va/en/102024/Energy/41729/Sonangol-signs-agreement-to-develop-green-hydrogen-project-in-Barra-do-Dande.htm.

[16] Gleiss Lutz. 2022. “Price Adjustment Clauses in Long-Term B2B Energy Supply Contracts: Is There a Wave of Lawsuits Looming?” https://www.gleisslutz.com/en/news-events/know-how/price-adjustment-clauses-long-term-b2b-energy-supply-contracts-there-wave-lawsuits-looming.;

Energy for Growth Hub. 2021. The Case for Transparency in Power Project Contracts. https://energyforgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Case-for-Transparency-in-Power-Project-Contracts_-A-proposal-for-the-creation-of-global-disclosure-standards-and-PPA-Watch.pdf.;

WBCSD and EY. 2020. Pricing Structures for Corporate Renewable PPAs. https://www.wbcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Pricing-structures-for-corporate-renewable-PPAs.pdf.

[17] European Union and Republic of Angola 2024, art. 18-21, 20-23.

[18] Interview with a green hydrogen industry expert (anonymous), by Rozenn Heim, April 15, 2025.

[19] Union and Republic of Angola 2024.

Author Bio:

Rozenn Heim is currently completing a Master’s in International Relations, specialising in European Union Studies at Leiden University (Netherlands). She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Literature and Humanities from Université Paris Cité (France) and King’s College London (UK), where she focused on the relationship between culture and politics, particularly through the lens of postcolonial studies. Building on this background, her interests centre on EU–Africa relations and on advancing an effective ecological transition through robust regulation and strengthening international cooperation. She also co-hosts International Insights – a podcast that explores world politics, foreign affairs, and diplomacy.