The question of what or who constitutes “Europe” is multifaceted. Artistic practices are indispensable in addressing such query, not only because they are vital in expressing and evoking feelings of belonging, but also because of their capacity to make visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate.[1] Artists and cultural actors are key in fostering awareness about the manifold nature of “Europe” and “Europeanness,” as they unveil inherent ambiguities in defining these concepts. This unveiling becomes particularly apparent in contexts where belonging to “Europe” or experiencing “Europeanness” is not self-evident. One of those contexts is the former Yugoslavia, where many artists and cultural actors have addressed the notion of belonging in their work since the conflicts of the 1990s.

This article focuses on three contemporary visual and performance artists in the former Yugoslavia and how they invoke new transnational and transitional spaces of belonging in Europe through their art. Driton Selmani addresses changing personal quests for belonging in Kosovo and in Europe, while Filip Jovanovski and Ivana Vaseva focus on the social impact of decaying socialist-era structures in the center of Skopje (the Republic of Northern Macedonia). The three artists use art to draw attention to and reflect (on) the flaws of contemporary societies and how these flaws affect notions of belonging. The article casts light on the singularity of these artists’ impact while also bringing to the fore the socially situated nature of artistic practices. Finally, the article describes the emergence of independent cultural and arts centers in the region to show that art is central in the way marginalized communities re-appropriate space.

The article shows how art can unlock new imaginaries because it can help people negotiate taken-for-granted spatial world orderings while providing alternatives to these orderings. Thus, art plays a crucial role in how people relate to each other, specific places, or memory. These social, spatial, and temporal dimensions of belonging are deeply interconnected and overlap.[2] They play a central role in artistic production that addresses how the self is relationally connected to the rest of the world. Lora Sariaslan has shown in her work on European-Turkish contemporary art that many artists have hyphenated identities that come alive through art. Artists’ multiple identities allow them to continuously oscillate “between the preservation of difference and the pursuit of similarity in contemporary cultures,” where “everything is transculturally determined.”[3] In the specific context of European belonging, hyphenated identities often entail being European and also a citizen of a specific (European) nation-state. However, people’s identities can also be linked to the city or region they live in, the community they are part of, or the European Union (EU) at large. The artists featured in this article can be considered to have hyphenated identities, since they are Kosovar-European or Macedonian-European. Likewise, the independent cultural centers discussed here connect to the local, post-Yugoslav, and European spaces in which they operate, leading to multiple interpretations of belonging.

Driton Selmani: artistic reflections on a rapidly changing world

Driton Selmani deconstructs artistic, cultural, social, and political topics. Born in 1987 in Kosovo—a landlocked country—he is part of the post-war generation of Kosovars who grew up in a climate of (political) isolation that provided few opportunities for artistic growth. The concept of periphery is thus central to Selmani’s work. He uses improvisation and humor to display his everyday experiences of in-betweenness and to express his positionality at the margins of Europe and as part of a country that no longer exists.

The photograph They say you can’t hold two watermelons in one hand (2012) (fig.1) shows Driton Selmani attempting to hold two watermelons in one hand. The work’s title refers to an Albanian saying that implies one’s inability to be in two places or roles at the same time, akin to the Turkish saying “One armpit cannot hold two watermelons” or the Persian version, “You can’t pick up two watermelons with one hand.”[4] The photograph was taken on a bridge at the Albanian-Kosovar border in a no man’s land. The choice of this location renders Selmani’s artwork an act of resistance and productivity and is reminiscent of bell hooks’s writings on how the margins can be productive spaces.[5] The background in the photograph shows the border between Albania and Kosovo as an incisive line on the mountain. This evocative, visible borderline brings to mind the saying that “borders are scars on the planet’s body”[6]; some scars are deeper than others. Through this artistic work, Selmani has inadvertently immortalized the site of the border, as the bridge has since been demolished through an agreement between the Albanian and Kosovar governments. It is precisely this marginal space of the borderland that speaks volumes to the rapid transformations of the region’s landscape.

Through the photographic medium, Selmani translates the Albanian proverb into an effective image by “freezing” this moment of impossibility, expressing his multiple positions—or hyphenated identities. Indeed, he is at once an artist, an Albanian, a citizen of Kosovo, a citizen of the Balkans, and a citizen of the world. The photograph displays the desire to stabilize the unstable and the impossibility of expressing the feeling of desolation inherent to the cultural and social structures that determine contemporary Kosovo. Selmani’s work engages in the demands capitalism makes on individuals today, especially in terms of multitasking. In an interview with one of the authors, he explains that “you can only hold two watermelons in one hand for so long, because it’s not natural.”[7] Through this work, Selmani defines different ways to be in-between: one can decide to hold the watermelons or let them go, or to believe or doubt. His work shows that people are pulled between the past and the future in a precarious and unwieldy world that holds many promises but also disappointments.

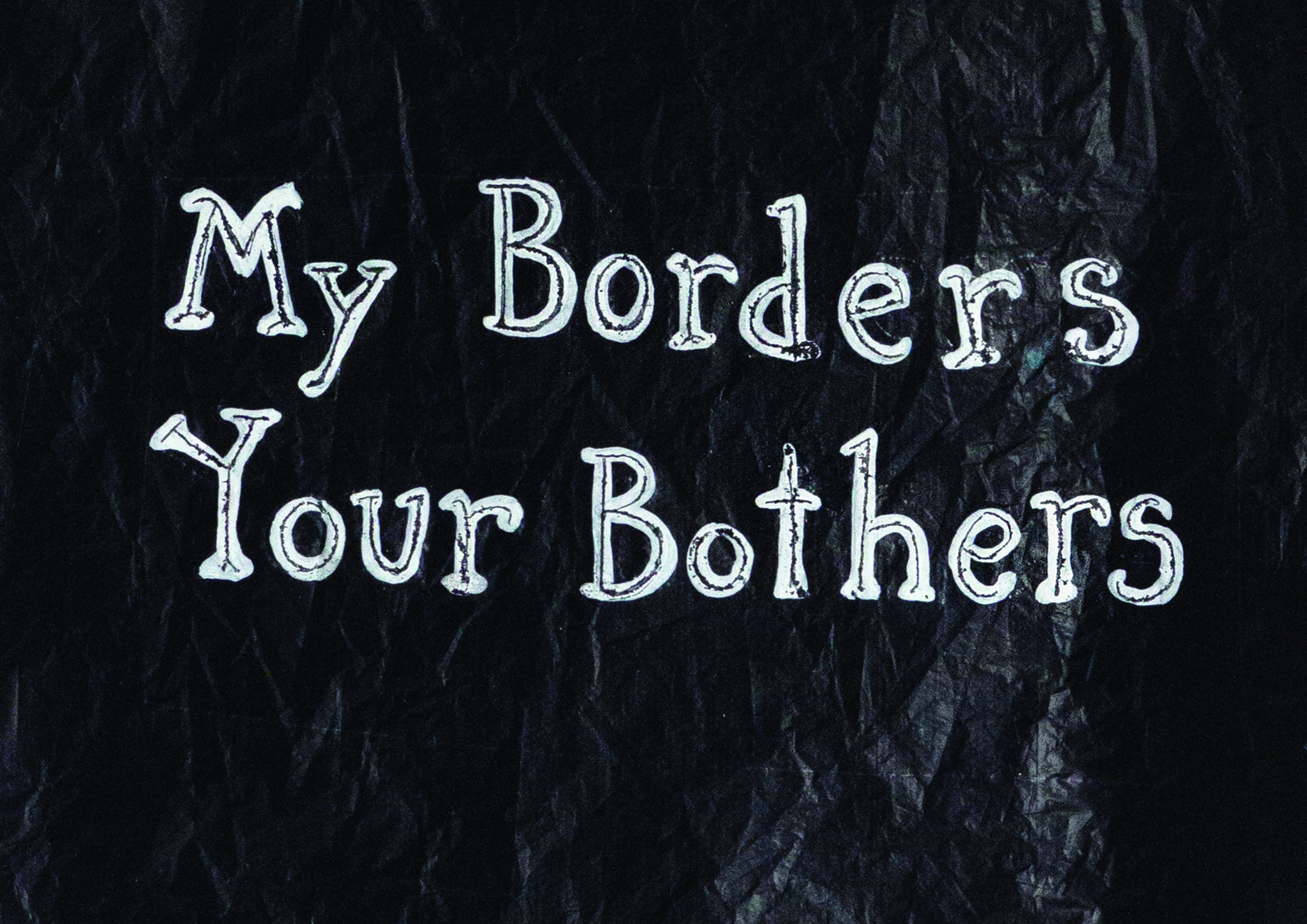

In the sculptural series Love Letters (figures 2 and 3), Selmani uses discarded plastic bags to share his realities and thoughts. He writes ironic messages on the bags, such as “Not to be used as a bag” or “Never say no to yes.” He was inspired by his wife who has been giving him lists of items to be bought and brought home or tasks to be completed. The Love Letters series is ongoing, as he keeps receiving his wife’s lists. Hence, this work also functions as a journal of his relationships, intimacy, and humanity. Selmani uses the plastic bags to convey personal and humorous messages but also to translate his position on historical and political matters; for example, he writes, “My borders your bothers” or “The irony of history is that history has no irony.” Therefore, the series speaks to social, historical, and political realities and draws renewed attention to the region in which Selmani grew up and lives. The discarded, colorful plastic bags present weighty ideas without any (physical) weighted material. In today’s visual vocabulary, the plastic bag, although banal and weightless, triggers debates about environmental harm and other serious matters.

The construction of (national) identity, the duality between the individual and the collective, and the interconnection between memory and history are at the heart of Selmani’s artistic practice. He instinctively and analytically responds to social and political changes happening in Kosovo and the world. His work also encapsulates his personal present and past, providing viewers with clues about where he belongs. Selmani deliberately unpacks his life trajectory and embraces the multiplicity of his modes of being. He uses artistic language and knowledge to withstand the grand narratives of history and allow for his own feelings of displacement and search for roots to come to the surface. Indeed, Selmani constantly interrogates borders (whether personal or national), geography, and belonging. His creative process is driven by the confrontation of his personal history and that of Kosovo. Whether he holds two watermelons or writes on plastic bags, Selmani continuously moves between past, present, and future.

Filip Jovanovski and Ivana Vaseva: artistic reflections on the erasure of the past

Filip Jovanovski and Ivana Vaseva are the two main representatives of the Faculty of things that cannot be learned (FR~U), an independent organization focusing on contemporary visual arts, culture, and education. FR~U recognizes art as a powerful catalyst for political change because of its ability to expose society’s imperfections.[8] Since 2015, Jovanovski and Vaseva have been involved in the development of a series of performative art projects in Skopje, the capital of the Republic of Northern Macedonia. Their performances If buildings could talk (2015- ), The Universal Hall in Flames–A Tragedy in Six Decades (2020), and Dear Republic (2021) have taken place in buildings that were built during the socialist era and are scattered throughout the city center. Jovanovski and Vaseva’s performances are a critical response to hegemonic neoliberal and nationalist politics. They saw how Nikola Gruevski’s government (2006-2016) led to a complete overhaul of Skopje’s city center in 2014.[9] The artists warn that political interventions caused the erasure of the traces of unity, solidarity, and responsibility that many of the city’s socialist-era buildings encapsulated. Their performances represent microcosms illustrating trends also occurring elsewhere in Europe, as neoliberal worldviews are increasingly overruling values focused on the commons and the collective and making individuals and communities feel marginalized and lose their sense of belonging.

FR~U performances

If buildings could talk (2015- ) is set in Skopje’s Railway Residential Building, which was built in the late 1940s as a social housing block for the Yugoslav railway company’s employees. When privatization policies threatened the future of the building, FR~U developed a performance to tell the forgotten stories not only of the building and its residents but of Skopje and the Republic of Northern Macedonia more generally. The artists guide the audience step by step into the history of the building, the city, and the country. The performance starts with a presentation of the building’s construction and follows with a description of people’s life during socialism, the 1963 Skopje earthquake, and the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. It concludes with an account of the post-conflict period and the transition from socialism to democracy. Jovanovski and Vaseva explore the past, present, and future of a public space in close collaboration with the local communities that have a stake in that space. As Vaseva argues: “The building has witnessed the transition from Yugoslavian socialism to current capitalism, from self-management ideas to ideas of privatization. It has also witnessed the alienation of the public good and the destruction of the commons, the collectivity, and public space.”[10] If the building could talk, the message would be: “how can we restore what is at risk of becoming lost—not only in this particular building but in Europe at large.”

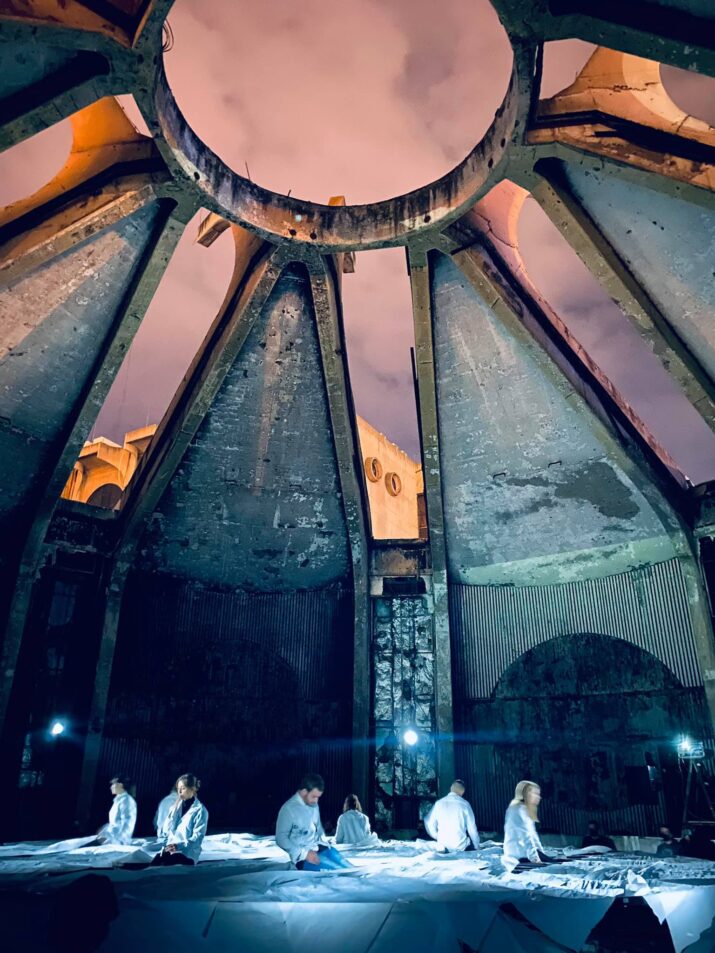

Another performance by Jovanovski and Vaseva is Universal Hall in Flame–A Tragedy in Six Decades (2020) (fig. 4). This work was set inside the now deserted Universal Hall, which was constructed in 1963 after the catastrophic Skopje earthquake, at a time when the city was known in the region as the “city of solidarity,” [11] as 77 countries helped the city to rebuild.[12] However, the Universal Hall was not rebuilt and instead was padlocked and left in disarray. On 20 July 2020, news spread about its possible demolition, motivating FR~U to take action and organize a performance in the building to convey two messages. First, they highlighted the loss that destroying the building would represent, as the Hall constituted a noteworthy example of brutalist architecture. Second, they underlined the importance of the solidarity that marked the foundation of the building in post-earthquake Skopje.[13] Building on Chantal Mouffe’s writings, Jovanovski and Vaseva warned that such demolition projects are detrimental to inclusivity in public spaces and thus to feelings of belonging, as they mute dissenting voices that are crucial to the preservation of a sense of community, responsibility, and solidarity.[14]

Finally, Jovanovski and Vaseva’s Dear Republic (2021) (figures 5 and 6) is a performance that took place at the Telecommunication Center in Skopje (also known as the Central Post Office), one of the best examples of brutalist and modernist architecture in the city.[15] Like Universal Hall, Dear Republic conveys that letting a building deteriorate leads people to forget its past. The original Telecommunication Center was destroyed during the earthquake but reconstructed as to reflect a vision for the new city and a different society. As a consequence of the 1963 earthquake, Skopje—a peripheral city until then—became a center of global cooperation and a late-modern urban laboratory for testing the latest urban and architectural paradigms.[16] In their performance, Jovanovski and Vaseva urge people to revisit this past and reappropriate Yugoslavia’s socialist past to imagine new and better futures. On the performance’s announcement, the artists reveal their longing for what has been lost and underline the need to safeguard the future of a country that seems to have lost its direction: “Our dear Republic, can we imagine you once more?”[17]

The three performances presented here address how the active marginalization of narratives about the past have negatively impacted notions of belonging in the region. Jovanovski and Vaseva observe how neoliberal practices of privatization, historical revisionism, nationalism, and xenophobia—when intervening directly in the public sphere—lead to communities’ exclusion, rootlessness, and disentanglement. The artists argue that these trends have not been limited to the Republic of Northern Macedonia but have emerged in all post-Yugoslav countries, where city centers have been drastically transformed and remains of the socialist past are fast disappearing, along with collective memory. With their collaborators, Jovanovski and Vaseva warn that the further erosion of the past may cause alienation and marginalization and obstruct alternative imaginations that are increasingly crucial in a Europe where similar patterns of neoliberalization, polarization, and exclusion—and thus of non-belonging—have emerged in many countries.

Cultural (art) centers: artistic reflections on experiences of non-belonging

Through their artwork, Selmani and Jovanovski and Vaseva stress the importance of the past in envisioning future trajectories—whether personal or societal. For them, the past is residual. While irreversible, it is still an effective element of the present.[18] The socialist past in the former Yugoslavia has become a site of inspiration to envisage new socio-political futures that are more inclusive than the present.[19] Similar trends can be discerned across independent cultural (art) centers emerging in the region—many established inside abandoned buildings built during the socialist era. These centers have literally and metaphorically become spaces for alternative socio-political imaginings. Already at the end of the 1980s, when Yugoslavia started disintegrating, representatives from the art world started to invest in the development of spaces in which multiple belongings could co-exist. Responding to increasing authoritarianism, censorship, and revisionism, these artists have critically engaged with their changing socio-political context.[20] For example, they have developed inclusive spaces and helped people feel that they belonged through unconventional art projects and new models of cultural management.[21]

Open spaces, spaces for openness

The entanglement of the Yugoslav past with alternative imaginings and future policies is exemplified by Magacin, a self-organized cultural center established in 2007 inside the building that hosted the former Yugoslav publishing house Nolit in Savamala in Belgrade, Serbia. The building is located in an old industrial area on the banks of the river Sava. Upon its opening, Magacin was meant to be an alternative and self-managed cultural center dedicated to exhibitions, theater plays, discussions, films, and educational programs. It has provided space for art forms and themes not generally supported by the national government. When opening the center, the organizers directly reacted to their constraining socio-political context. Since then, they have fought the commercialization of the cultural sector, the continuous neglect, politicization, and use of culture by politicians, and nepotism in the sector. They have also countered people’s deteriorating attitude towards culture as a public good and the lack of institutional pluralism and democracy within the art sector.[22] Magacin thus embodies inclusivity by proposing alternative forms of governance— for example through an open calendar and free access to space for independent cultural workers. The center provides exhibition and performance spaces and allows artists to develop projects otherwise excluded from Serbia’s public sphere. By insisting on the democratization of the cultural sector, Magacin allows for the co-existence of multiple forms of belonging where belonging has become marginalized. It accommodates the work of artists who are firmly embedded within their local and regional contexts, as they draw on post-Yugoslav networks to resist growing nationalism and xenophobia. At the same time, these artists are deeply connected to Europe through their cultural and artistic expression, networks, and funding.

Another example of a cultural center in post-Yugoslavia that has actively invested in the accommodation of alternative imaginings in the face of constraining socio-political conditions is the Center for Contemporary Culture, or KRAK. It is located in Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the abandoned headquarters of a former textile factory, Kombiteks. The name “KRAK” derives from the abbreviation of “Kombiteks Workers’ Club” (Klub Radnika Kombiteksa), pointing to the importance of preserving the local industrial heritage and labor culture of Yugoslav socialism. KRAK closely collaborates with local communities whose history is intertwined with the textile factory and Bihać’s industrial past. Initially, KRAK was developed through international funding schemes; however, since 2018, it has been supported by the Bihać City Council.[23] Like Magacin’s projects, those initiated by KRAK derive from specific socio-political circumstances resulting from a neglected industrial past, ethno-national conflict, post-war post-traumatic experience, poverty, and depopulation.[24] In creating KRAK, its founders reacted to the cultural devaluation caused by corruption, nepotism, and right-wing tendencies typical of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s dysfunctional government. They believe that culture, science, and art can respond to the ongoing crises and socio-political environment and that they should be the drivers of social change. They argue that art and culture can provide important frameworks not only for individuals but also for communities and society.[25]

What unites KRAK and Magacin is that they provide alternative spaces for cultural engagement in political situations in which citizens are increasingly disempowered.[26] These spaces can be seen as self-made spaces, as they are reclaimed and re-appropriated for temporary events and informal gatherings often created by and for marginalized communities.[27] They often function as counter-public spheres—in parallel to official public spaces—where audiences can actively engage in topics that politicians systematically avoid, such as minorities, the complexities of the Yugoslav past, and the politics of memory institutionalized after the 1990s conflicts. In those spaces, marginalized communities can channel their dissatisfaction, develop alternatives to the status quo, and express their creativity and free thinking. Magacin and KRAK have enabled people involved in the art scene in post-Yugoslavia to experiment with different forms of community-based resource management and co-production; hence, they have had a significant role in opening new perspectives for social and political transformation.[28]

Why art matters

Artworks and the sites from which they emanate highlight that Yugoslavia’s past and its afterlives are curiously entangled. The artworks and cultural centers discussed in this article present various imaginaries of Europe and lead to a reflection on what it means to be “European,” as they reveal the complexity of people’s quest for belonging in Europe. Navigating the borders between cultures, identities, and languages, the artists and cultural actors featured here work through and despite the challenges of their respective positionalities. They are able to visualize experiences of displacement and provide alternative imaginations in and of Europe as they are rooted in a “semi-periphery.” These positionalities make them both different from and similar to the rest of Europe. Art offers powerful means to interrogate major historical events such as the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the alternation of actual or imaginary borders, and the emergence and collapse of socialism in the region—the latter leading to increased authoritarianism and growing xenophobia in the Balkans.

The notion of belonging is complex in post-Yugoslav Europe; nonetheless, resistance, hope, and delight remain. In their work, artists and creators of culture in the region actively engage with the residual Yugoslav past, connecting it to the challenging present. Through imagination and improvisation, they expose their respective societies’ imperfections and stimulate awareness about the complexity of belonging in Europe. By reflecting on post-war transformations in the Balkans, they show how losing memory also means losing place, belonging, and roots. They demonstrate that, without intervention, feelings of displacement and rootlessness might lead to undesirable futures. Artists carry the past to fashion a future firmly grounded in Europe. Their creativity and endurance confirm the importance of artistic practice in gaining an understanding of the multiplicity of belonging in Europe and in bringing awareness about the power of art to make sense of the world.

Lora Sariaslan is an art historian and Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at Utrecht University. Her academic focus is on transnational art practices, identity politics, mobility and migration, and mapping. She specializes in modern and contemporary cultures, approaches to curating, and critical museum practices that transform collecting and presenting artifacts. In addition to being an academic, she was curator at Istanbul Modern (Turkey) and assistant curator at the Dallas Museum of Art (Texas, US).

Claske Vos is an anthropologist and Assistant Professor at the Department of European Studies at the Humanities Faculty of the University of Amsterdam. Her current work lies at the intersection of EU funding, cultural activism, and EU enlargement. Her expertise is in European cultural policy, cultural heritage, Southeast Europe, and European identity formation.

[1] Chantal Mouffe, “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces,” Art & Research. A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1, no. 2 (2007): 1-5 and Sachs Olsen, Cecilia. “Urban space and the politics of socially engaged art.” Progress in Human Geography 43, no. 6 (2019): 985-1000.

[2] Susannah Eckersley and Claske Vos. Diversity of belonging in Europe: public spaces, contested places, cultural encounters (London: Routledge, 2023), 3.

[3] Lora Sariaslan, “Pins on the Map: Urban Mappings in European-Turkish Contemporary art.” PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2022; Carmona Rodríques, Pedro Miguel. “Hyphens, Boundaries and Third Spaces: Identity and Cultural Policies in Afro-Caribbean-Canadian Writing.” Revista de Filologia (2006): 57.

[4] Parts of the text on Driton Selmani draws on Sariaslan, Lora. “Hidden in Plain Sight.” In Hidden in Plain Sight: Driton Selmani, edited by Lora Sariaslan, 30-45. Prishtina: SBunker, 2021.

[5] bell hooks, “Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 36 (1989): 15–23.

[6] Sariaslan, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” 33.

[7] Driton Selmani, interviewed by Lora Sariaslan.

[8] Filip Jovanovski and Ivana Vaseva, interviewed by Claske Vos.

[9] See Jovanovski, Filip, Ivana Vaseva. and Kristina Lelovac, “This Building Talks Truly.” In Radical Housing. Art, Struggle, Care, edited by Ana Vilenica, 210-219. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

[10] Ivana Vaseva, “The Railway Residential Building – Performative Experience that Reminds us of our Responsibility.” In This Building Talks Truly, edited by Ivana Vaseva and Filip Jovanovski, 13. Skopje: Datapons, 2021.

[11] Ivanovska, Ana Deskova, Vladimir Deskov and Jovan Ivanovski.” Building the City of Solidarity: The Case of Post-earthquake Reconstruction of Skopje.” In Solidarity – from overcoming crisis to sustainable development, edited by Nenad Markovikj and Ivan Damjanovski, 10-16. Skopje: United Nations Development Programme North Macedonia.

[12] Trajanovski, Naum. “The City of Solidarity’s Diverse Legacies: A Framework for Interpreting the Local Memory of the 1963 Skopje Earthquake and the Post-earthquake Urban Reconstruction.” Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics 15, no. 1 (2021): 30-51.

[13] Frangovska, Ana. “Trans-Tactical Performance Actions as an Antagonistic Form in Dealing with the Hegemonic Forms of Neoliberal Policies of Power.” AM Journal 27 (2022): 44.

[14] Chantal Mouffe, On the political, (London: Routledge, 2005).

[15] The team behind the performance: Filip Jovanovski: artist and performance development, Kristina Lelovac: performer and performance development, Ivana Vaseva: curator, Viktorija Ilioska: choreographer, Emilija Chochkova: producer.

[16] Ivanovska Deskova, Ana, Vladimir Deskov and Jovan Ivanovski, “Challenging Disregard: The Case of the Telecommunication Center in Skopje.” Seasoned Modernism, Prudent Perspectives on an Unwary Past (2017): 205-219.

[17] “Dear Republic Performance Essay,” Ivana Vaseva, accessed 10 June 2024, https://issuu.com/ivana.v/docs/dear_republic/1.

[18] Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 122.

[19] Tania Petrović, “Towards an Affective History of Yugoslavia.” Filozofija i Drustvo 27 no.3 (2016): 504–520.

[20] Hadjievska Ivanovska, Milka and Jasmina Zaloznik. “Topology of Space of the Independent Scenes in Serbia and Macedonia.” Performance Research 20 no.4 (2015): 90-95. Vukobrat, Jelena. Shrinking spaces in the Western Balkans. Sarajevo: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2016.

[21] See Vos, Claske. “Establishing a place in the European cultural space. Grassroots cultural action and practices of self-governance in Southeast Europe.” In Diversity of Belonging in Europe: public spaces, contested places, cultural encounters, edited by Susannah Eckersley and Claske Vos,740-760, London: Routledge, 2023, and Vos, Claske. “Deliberation through Contestation: EU investments in cultural and artistic spaces beyond the EU.” Continuum (forthcoming).

[22] Čukić, Ivana, and Milica Pekić, “Magacin as a Common Good.” In Magacin: A Model for a Self-organized Cultural Centre, edited by Iva Čukić, Ana Dimitrijević, Lana Gunjić, Luka, Knežević-Strika, Jelena Mijić, Milica Pekić, Aleksandar Popović and Sanja Radulović, 12. Belgrade: NKSS, 2019.

[23] See “About KRAK,” KRAK, last accessed 3 April 2023, https://www.krak.ba/en/about.

[24] Hošić, Irfan. Culture Front Bihać. #Defend Gallery. Bihać: Udruženje Abc:2017, 7.

[25] See “About KRAK”, KRAK, last accessed 3 April 2023, https://www.krak.ba/en/about.

[26] Vos, “Establishing a place,” 740-760 and Vos, “Deliberation through Contestation” (forthcoming).

[27] Eckersley, Susannah, Claske Vos, Grazyna Szymańska-Matusiewicz, Malgorzata Głowacka-Grajper, Joanna Wawrzyniak, Helen Mears and Bruce Davenport. “Supporting inclusive spaces: enabling recognition in diverse cultural and community spaces, en/counter/points.” Policy Brief 1 (2022) https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/282695.

[28] Čukić, Iva and Jovana Timotijević. Spaces of commoning: urban commons in the ex-YU region. Belgrade: Ministry of Space: Institute for Urban Politics, 2020, 44.

Published on August 15, 2024.