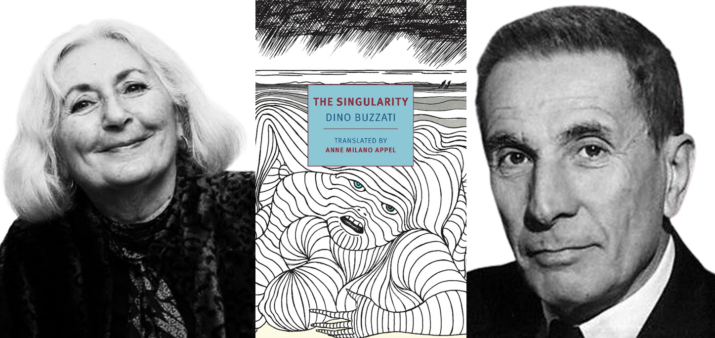

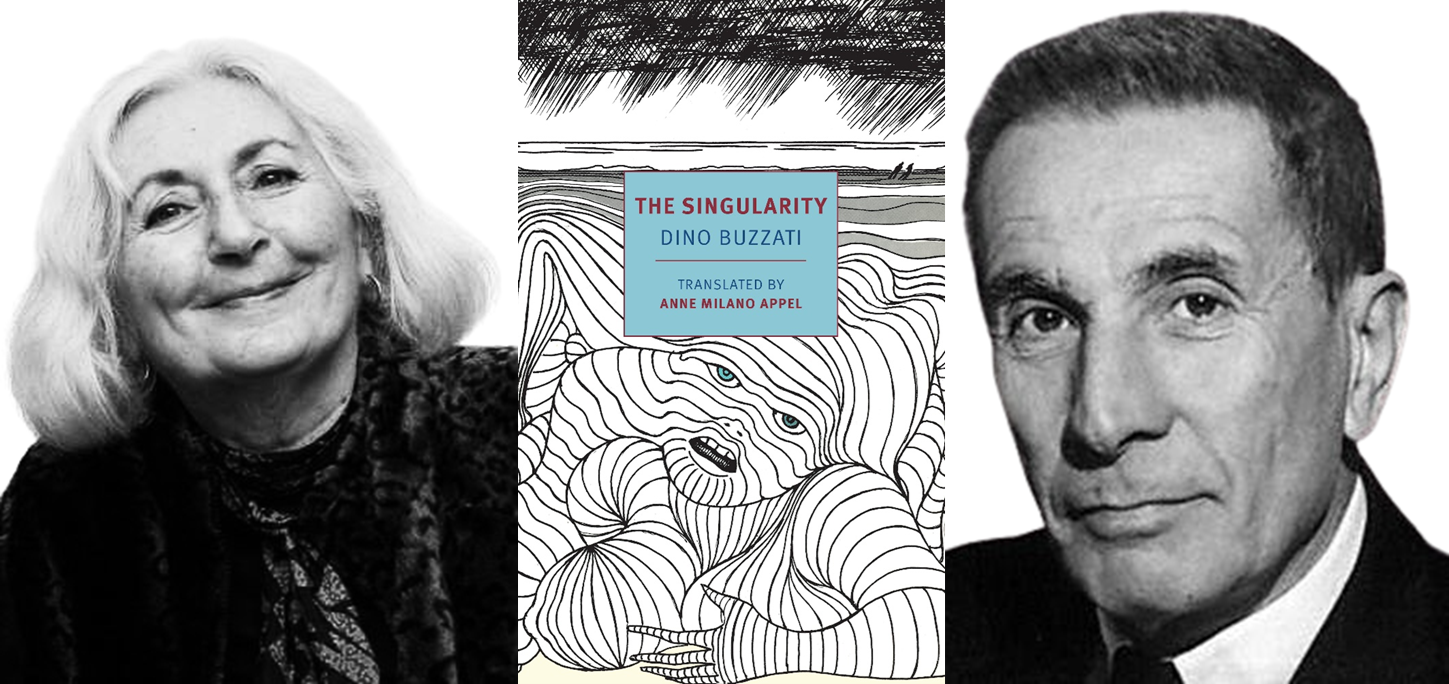

Translated from the Italian by Anne Milano Appel.

“Would you be willing, professor,” the colonel asked in a different tone, enunciating the words clearly, “would you be willing to relocate to one of our military zones for a minimum of two years, to participate in a mission of vital national interest, as well as extraordinary scientific value? As far as your position at the university goes, you would ostensibly be on official assignment with full salary, that goes without saying, plus a substantial emolument for the mission itself. I am not able to specify the exact sum but it would be somewhere in the neighborhood of twenty- to twenty-two thousand liras per day.”

“Per day?” Ismani exclaimed, dumbfounded.

“Plus spacious, comfortable accommodations, equipped with all the modern conveniences. The location, I read here, is extremely salubrious and delightful. Cigarette?”

“Thank you, I don’t smoke. But what does the work involve?”

“The ministry’s nomination itself, it seems to me, implies that your specific skills were taken into account … Once the mission has been carried out, of course, the government will not fail to substantially show its … also taking into account the undeniable sacrifice of residing—”

“Why? Wouldn’t I be able to leave there?”

“The very importance of the task—”

“For two years? And the university? What about my classes?”

“I can assure you—although I, as I’ve said, am uninformed as to the nature of the project—that you will be given the opportunity to do some exceedingly interesting research … Though to be honest I must add that there has never been any doubt here as to what your answer would be.”

“And with whom?”

“I am not able to answer that. However, I can mention a name, a great name: Endriade.”

“Endriade? But he’s in Brazil right now.”

“Yes, of course, in Brazil. Officially.” The colonel winked.

“Now, now, professor, there’s absolutely no reason to be upset. You’re a little anxious perhaps, am I right?”

“Me? I don’t know.”

“Well, who isn’t anxious given the frantic life we lead today? In this case, I assure you, such feelings would be totally out of place. The proposal, it’s my duty to stress, is meant to be flattering. Then too, there’s no rush. Go home, professor,” he said with a smile, “go on with your usual life as if I hadn’t told you a thing … Understand? … As if you had never set foot in this office … Think about it, though … Think about it … Should you want, give me a call.”

“What about my wife? You know, colonel, you may laugh, but we’ve only been married a short time, less than two years.”

“Congratulations, professor,” the colonel said, wrinkling his brow as if considering a difficult problem. “However, it doesn’t necessarily mean … If you would personally vouch for her …”

“Oh, my wife is such a simple creature, so naïve, there’s no danger that … Besides, she has never been interested in my research.”

“All the better that way, I think.” And the colonel laughed. “Colonel, before—”

“What is it, tell me.”

“Before deciding one way or another, wouldn’t it be possible for me to …?”

“Know more about it, you mean?”

“Well yes. Being asked to drop everything for two years without even knowing what—”

“Indeed, professor, on that point you will have to be patient. I can give you my word that I know nothing more than what I have told you. That’s not all. You may not want to believe this, but as regards the precise task that will be assigned to you, I’m afraid there isn’t a single individual in the entire ministry—not one, understand?—who is capable of telling you what it is. It seems ludicrous, I know. Not even the chief of staff, perhaps … At times the military’s top-secret machinery rises to the level of absurdity. Our job is to protect the secret. What’s concealed inside it, however, is none of our concern. Ah, but you will have time to find out all about it, all the time you want, in two years, I’d say—”

“Excuse me, then how did you happen to choose me, for example?”

“Us? It certainly wasn’t us. The recommendation, the suggestion came from the zone itself.”

“From Endriade?”

“Don’t put words in my mouth, professor. It may have been Endriade but I don’t know that for certain … No, no, professor, there’s no hurry. Go back to your classes as if I hadn’t said a word to you. And thank you for coming. I don’t want to take up any more of your time.” The colonel stood to accompany Ismani to the door. “There’s absolutely no rush … But think about it, professor. And should you decide …”

*****

Ismani and his wife left for “military zone 36” in early June, in a car belonging to the Ministry of Defense. A soldier was driving it. They were accompanied by Captain Vestro, a staff officer, about thirty-five years old, stocky, with small beady eyes and an ironic look.

At the time of departure, the Ismanis knew they were headed for Val Texeruda, a well-known vacation area, where Elisa had also vacationed as a girl, many years before. But they didn’t know any more than that. Rising to the north of Val Texeruda was an extensive range of mountains. Maybe the destination was up there, in some remote spot hidden away among the rock faces, or in the woods, or in an alpine village cleared of its inhabitants and transformed into a military base.

“Captain,” Mrs. Ismani asked, “where exactly are you taking us?”

Vestro spoke slowly, as if searching for his words one by one, perhaps out of prudence, almost as if he were afraid of letting some restricted information leak.

“Here, ma’am,” he replied, showing her a typewritten sheet of paper, though not handing it over to her. “This is the appointed itinerary. Tonight we will stop at Crea. Tomorrow morning, departure at eight thirty. The state highway as far as Sant’Agostino. From that point there’s a military road. I will have the pleasure, and the honor, of accompanying you to the checkpoint. There my charge will end. Another car will come to pick you up.”

“But you, captain, have you ever been there?”

“Where?”

“Military zone 36.”

“No, ma’am, I’ve never been there.”

“What is it? An atomic plant?”

“An atomic plant …” the officer mused in a vague tone.

“That will be interesting for the professor, I imagine.”

“But I was asking you, captain.”

“Me? But I don’t know anything about it.”

“You will admit then that it’s quite curious. You know nothing, my husband knows nothing, at the ministry they know nothing. In fact at the ministry they were extremely reticent, weren’t they, Ermanno?”

“Reticent? Why do you say that?” Ismani said. “They were very courteous.”

Vestro smiled faintly.

“So you see I was right?” Elisa asked.

“Right about what, sweetheart?”

“That they called you for the atomic bomb.”

“But the captain didn’t say that.”

“Well then,” the woman insisted, “what do they do in this military zone 36 if it’s not the atom bomb?”

“Careful, Morra,” the captain exclaimed, not weighing his words this time, since they were passing a huge truck and the road was rather narrow. Though actually there seemed to be no reason to be alarmed. It was a long straight stretch and no one was approaching from the other direction.

“As I was saying,” Elisa Ismani went on. “I said that if it’s not the atom bomb, what do they do in this place we’re going to? And why won’t they tell us? Even if it were a military secret, we, it seems to me … rather than going there in person …”

“You referred to an atomic plant.”

“Not referred to. I was only asking.”

“Well, ma’am,” Captain Vestro said, his answer strained, “I think you will have to be patient until you get there. I assure you that I am not in a position to tell you.”

“But you know, don’t you?”

“I told you, ma’am, I have never been there.”

“But you know what it is they do there, don’t you?” Ismani listened nervously.

“Look, ma’am, and forgive me for being pedantic, there are three possibilities: either it isn’t a secret but I don’t know what it is; or I know but it’s a secret; or it’s a secret and on top of that I don’t know what it is. You see that in any case—”

“But,” Elisa objected, “you could tell us which of the three cases it is.”

“The second,” the officer countered, “depending on the level of secrecy. If it were classified top secret, as is often the case in operational plans, for example, it would even ex-tend—and the rule expressly prescribes it—to everything that concerns it, even remotely and partially, even indirectly and negatively. And what does negatively mean? It means that if someone knows that there is such a secret but doesn’t know what it is, he is even forbidden to reveal that he doesn’t know it. And note, ma’am, that though the restriction is seemingly absurd, it has its good reasons. Take our case, for instance, military zone 36. Well then, simply admitting that I am not informed, given my rank and functions, might provide a clue, albeit minimal, to someone who—”

“But you know who we are!” Mrs. Ismani exclaimed irritably. “The very fact that you are taking us there excludes, I would say, any possibility of suspicion.”

“Ma’am, at the entrance to the Military Academy—I imagine you’ve never been there—there is an inscription in the vestibule: ‘Secrets have neither family nor friends.’ This can be harsh, in certain situations, difficult and objectionable to those close to you, I admit …” He trailed off, he seemed exhausted by the long explanation.

Mrs. Ismani laughed. “So, you are diplomatically telling me that you can’t, or won’t, tell us what’s at this celebrated military zone?”

“But, ma’am,” the captain explained with his didactic imperturbability, “I never said I knew.”

“All right, enough. I was a bit petulant. I’m sorry.” The officer was silent.

About five minutes went by, then Ismani timidly spoke up. “Forgive me, captain. You said there were three possibilities. Actually, there are four. Because it might also be that the matter is not secret and that you know what it is.”

“I didn’t propose that case,” Vestro explained, “because it seems superfluous.”

“Superfluous?”

“That’s right. In that case … if that were the case I would have told you everything a long time ago! Watch it, Morra!” But the warning to the driver was also superfluous: the curve they were approaching was very gentle and the car wasn’t doing more than thirty-five.

Dino Buzzatti (1906-1972) was an Italian writer, poet, and journalist. He wrote works of fiction, short stories, theater plays, and librettos. He was also an artist and painter.

Anne Milano Appel has translated works by a number of leading Italian authors for a variety of US and UK publishers. Her work on Daniele Del Giudice has appeared in Translation Review and Massachusetts Review. Her translation of his final novel Orizzonte mobile is currently seeking a publisher, and Lo stadio di Wimbledon will soon appear in English from New Vessel Press as A Fictional Inquiry.

This excerpt from THE SINGULARITY was published by arrangement with NYRB Classics and The Italian Literary Agency. Copyright © Dino Buzzati Estate. English translation copyright © Anne Milano Appel 2024.

Photo Dino Buzzatti: Public domain | Photo Anne Milano Appel by Andrea Price.

Published on August 15, 2024.