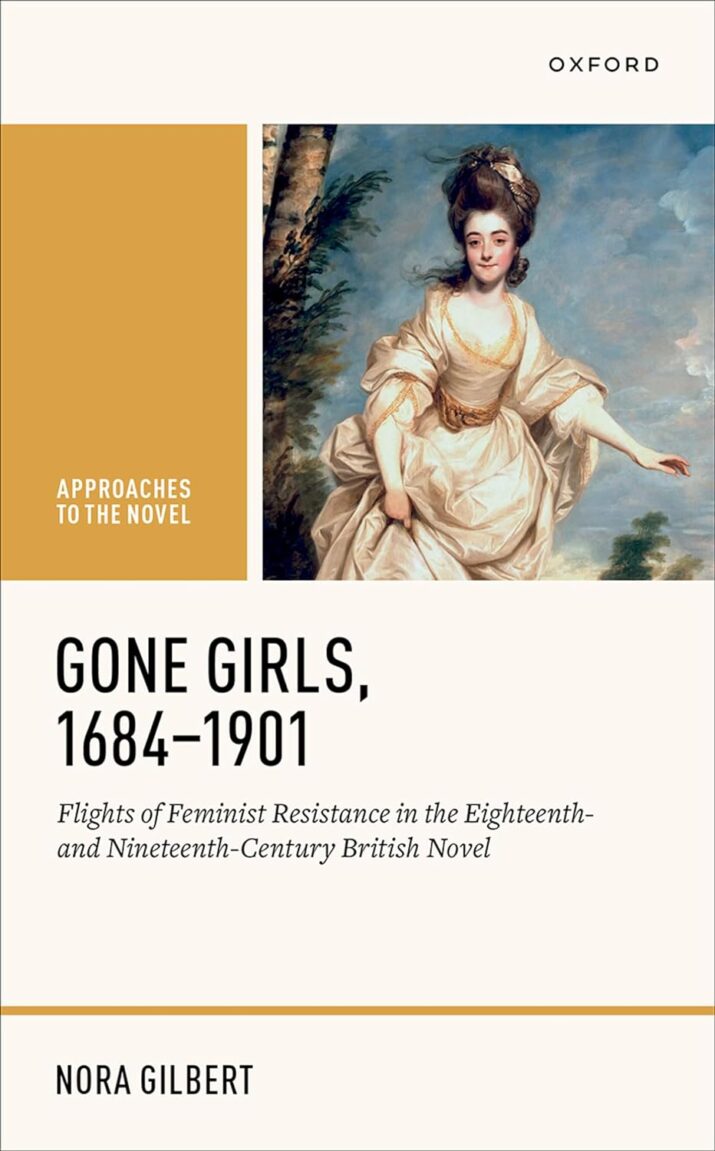

Gone Girls, 1684-1901: Flights of Feminist Resistance in the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century British Novel by Nora Gilbert

A moment of confusion in the garden. A quick step down the stairs and into the night. A faked death and a new identity. A vengeful escape with a male suitor. Female characters in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British novels are constantly (and cleverly) running away and, indeed, they have much to run away from: ruinous temptations, suffocating environments, patriarchal confinements, sexual violence, rape. They also, however, sometimes run towards what they desire: social freedom and independence, class mobility, revenge, sex. In doing so, they echo, complicate, and reimagine acts performed by their real-life contemporaries. As Nora Gilbert outlines in the opening of Gone Girls, 1684-1901: Flights of Feminist Resistance in the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century British Novel, the trope of runaway women emerges following the highly publicized trial concerning Henrietta Berkeley, who at the age of seventeen ran away with her older sister’s husband, Ford Lord Grey, on the night of August 19, 1682. The courts refused to acknowledge her agency in the scandal, but, as Gilbert argues, the publication of Aphra Behn’s Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684-87), which was inspired by the scandal, begins a narrative trend of novels that give voice to runaway women and the parts they play in their departures from “home.”

As Gone Girls goes on to persuasively argue, focusing on the narrative moments when female characters decide to run away within these novels––when they finally cross that threshold and why––provides a new avenue into understanding the histories of the rise of the novel and of modern feminism. These moments where women break the patriarchal social order, Gilbert argues, are significant for the ways in which they elicit readerly sympathies despite contemporary attitudes surrounding such daring acts of female rebellion. And acts of rebellion they are––as the introduction’s title, “Flight as Fight,” highlights, female flight is “a form of fight,” one that allows female characters an active and willful defiance (15). Gilbert’s method of focusing on these moments contains its own tinge of rebelliousness, as bringing attention to the significance of these moments of female flight emphasizes the novel’s middle (where the moment of female flight, or telling of the flight, typically occurs) as a radical narrative space. In turning her attention to the importance of narrative middles as opposed to narrative beginnings or endings, Gilbert builds on work by Caroline Levine and Marco Ortiz-Robles, contributing and adding nuance to studies on the rise of the novel. Additionally, Gilbert’s argument is a welcome addition to studies of feminism in its attention to successful runaway women and those who return to the domestic order; this focus differentiates her approach from the well-trodden field of studies on the “fallen woman” narrative. As Gilbert notes, even in these cases of return to marriages, fathers, and other patriarchal structures, moralizing endings that would seem to overwrite the central act of female rebellion actually fail to do so, further prioritizing the significance of middles over endings.

Gone Girls chases the figure of the female fugitive through the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries in a well-organized manner, emphasizing the evolution of the novel’s form and literary genres as well as the development of the runaway-woman trope. The introduction is followed by seven chapters that are roughly chronological, each focused on one literary genre (amatory fiction, sentimental fiction, gothic fiction, the novel of manners, provincial fiction, sensation fiction, and New Woman fiction, respectively) and divided into further sections that closely examine the novels of particular authors. This trajectory traces out evolving social concerns regarding female mobility, desires, and independence and how these concerns both shape and are shaped by different literary genres. At the turn of the twentieth century, the figure of the runaway woman in British fiction apparently finally comes to a stop. In the epilogue, Gilbert notes that as women gained rights––both within and outside of the home––the runaway woman plot drops away from British novels. However, female flight perseveres in visual media through Hollywood film, heavily borrowing, as Gilbert argues, from British novels.

One of the strengths of Gone Girls is its close reading of how the trope of the fugitive woman functions within distinct genres––particularly when those genres demand that female characters follow the rules––and the relationship between those genres and reader sympathies. These close readings are especially strong in the chapters focusing on the early- and mid-nineteenth century, as literary genres became preoccupied with representing and upholding social customs. In her fourth chapter, “The Ones Without the Manners,” Gilbert considers the runaway woman plot in the novel of manners, a form distinguished by its detailed attention to the values, traditions, and restrictions of society. To preserve the need for the female protagonist as an ideal figure, Gilbert argues, the runaway woman plot takes on the supporting role. As Gilbert persuasively shows in her reading of Jane Austen’s novels, it is a close female relation who runs off, allowing the female protagonist to learn from that relation’s actions (she now knows what not to do). In this clever analysis of Austen’s works, Gilbert not only produces new readings of these novels, but she also compellingly argues for the significance of both narrative middles and supporting characters who critically shape the decisions and nature of the model heroine. She also suggestively reestablishes these fleeing female relations as heroines in their own right for while all of the other characters may judge this unfortunate relation, Gilbert argues that the reader is not necessarily asked to do the same. Rather, Austen elicits the reader’s sympathies. This attention to readerly sympathies and how eighteenth- and nineteenth-century authors sympathetically portray female acts of defiance is another of Gone Girls’s notable aspects. As Gilbert notes, it is important that “we know Jane’s flight from Rochester to be the very antithesis of a moral ‘fall’” or that Clarissa Harlowe’s escape with Lovelace provocatively blurs the lines between a deceitful abduction and willful flight (131). As Gilbert charts in her semi-chronological movement from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, the British novel became increasingly adept at eliciting––and complicating––these readerly feelings.

To reach these conclusions regarding runaway-women narratives, Gone Girls focuses on scenes of female flight from forty novels written by twenty-five authors (almost, but not all, women, and including both canonical and less well-known writers) spanning a little over two-hundred years. The span of novels and genres that Gilbert covers is impressive, but, as she acknowledges at several points, there is one notable “runaway” figure and form of fugitive fiction that is absent from Gone Girls: that of the “runaway slave.” However, through its attention to historical and legal narratives as well as novelistic ones, Gone Girls persuasively makes the case for the significance of the runaway-woman narrative as both historical event and fictional trope; in fact, Gilbert’s deft movement between legal records, historical details, and close readings will make this book of interest to scholars interested in women’s studies and British legal history as well as literary critics.

Although Gone Girls focuses on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain, its epilogue focuses on runaway women in Hollywood film; moreover, the title, Gone Girls, points to the continued widespread presence and effects of the runaway-woman trope across media, time, and space, even as women gained rights and mobility. The term “gone girl” comes from Gillian Flynn’s 2012 novel, Gone Girl, and the 2014 film of the same name. At first glance, a “gone girl” would seem to refer to a female character who has disappeared, who is, quite literally, “gone.” But as Flynn’s novel goes on to show, a “gone girl” is actually still very much present: Amy, the gone girl of Flynn’s narrative, turns out to have orchestrated her own disappearance so that it appears that her husband, Nick, has murdered her, and, in the end, she returns to her marriage. She is, in fact, never really “gone,” continually powerfully exerting her influence on other characters as well as her reader, even when she is not physically present. Gone girls, then, through Gilbert’s model of “flight as fight” continue to make their presence felt even in their absence––an effect that Gone Girls, too, has upon its readers, eliciting and complicating our sympathies. Just as the gone girls of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century novels continue to impact other characters and readers, Gone Girls will keep influencing our reading of histories of the novel and feminist movements well after we close the final page.

Don’t you see, dear reader, how she runs?

Brianna Beehler received her PhD in nineteenth-century literature from the University of Southern California. Her dissertation, “Dollplay: Narrative Rituals in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” was supported by a 2020-2021 Mellon-Council for European Studies Dissertation Completion Fellowship. Her articles and reviews have appeared in ELH, Nineteenth-Century Literature, The Georgia Review, and elsewhere.

Gone Girls, 1684-1901: Flights of Feminist Resistance in the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century British Novel

By Nora Gilbert

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Hardcover / 240 pages / 2023

ISBN: 9780198876540

Published on August 15, 2024.