Translated from the Ukrainian by Zenia Tompkins and Nina Murray.

I was moving toward the door slowly, trying to maneuver the bag on my head so that I could at least see the floor, when I heard another command: “Take the bag off!”

This was another trick Palych played brilliantly. The bag, you see, was an inextricable part of life for all newcomers. Everyone there wore a hood all the time. They once summoned a guy upstairs to perform some job— to move bricks from one place to another in a wheelbarrow or something. Palych wouldn’t let him take the hood off even to work. That was part of his intimidation strategy, of course, and it also provided a means to reward someone by letting them go without the hood, thus indicating that they were in favor. For me, however, that one instance remained an exception, and I wore the hood for the next eight months, even to the exercise yard located forty-five feet from the cell.

I must admit that I was less scared with the hood on than when I took it off. I faced a very tall man, dressed in camo and holding an AK‑47. He grabbed me by the neck and held me up against the wall while closing the door with his other hand. He was so massive that I wondered why he bothered with the machine gun at all.

It turned out that our cell wasn’t the only room in the basement. I saw two more doors, one leading to the disciplinary unit, known as the Cooler, and the other into a solitary cell. The man’s fingers tightened on my neck again, and he slowly dragged me up the stairs. I thought once more that wearing the hood was preferable because it didn’t let you see how hopeless everything looked: the vault-like door with a twist lock like in a submarine, the thick walls, the damp darkness of it all. Yet what I was about to see did even more to rob me of any hope for reason.

The giant in camo and combat boots delivered me to a room with a couch. On the couch lounged a heavyset man, who was dressed in shorts, a T-shirt, and beach flip-flops. He was also armed with a machine gun and seemed to be playing with it rather absentmindedly. My escort sat on the couch next to him but assumed a formal posture: this was his superior. I sat in the chair I was pointed to. I had no idea who these people were or what was about to happen.

“Introduce yourself: your name and the charges.

“In the space between us stood a giant flat-screen monitor divided into a dozen rectangles, each of which showed ant-sized inmates in different cells, including in our basement. It was here, in the Monitoring Room, that management made its decisions: who was going tube beaten and put under the cot tonight, and who would-be spared.

I gave my name and charges as instructed and inquired, “You must be the shift leader?

“The man in the T-shirt grinned and said, “I’m the leader, period. I’m the Boss here.”

Only then did I realize who I was talking to. This man in rubber flip-flops and a funny T-shirt, with his gun, was the infamous monster I had heard about. Amazingly, he continued to address me with a formal “you,” like any polite adult, except he kept whirling his machine gun as if it were a plastic toy. In the course of that first encounter, Palych never raised his voice or insulted me, though it was his well-known habit to address inmates by a variety of derogatory terms, the least offensive of which were “shit” and “faggot.”

“Tell me honestly,” he said. “Have you had suicidal thoughts?

“My astonishment at being asked this question was a clear consequence of my lack of experience on the inside, where everyone knows that walls have ears. Obviously, Palych had at his disposal not only my file from the Office, but also reports by covert observers that included people in my basement cell. I understood that lying was useless and said to him honestly, “Yes, I have.”

“You shouldn’t do that here. This is a warning. It will only make things worse for you. Is that clear?

“I nodded in affirmation, even though I couldn’t imagine at that moment what could be worse than suicide and how I was to interpret his warning. Two years later, a man who, at that moment, could be seen on the monitor calmly walking around would end up in the Cooler next door. By then he would become so disturbed that he would start cutting his face with a dull metal spoon and throwing himself against the bars of the basement windows. In the Cooler, he would break off shards of tile and slice open his wrists. He would be bandaged up and then chained by his uninjured hand to the Cooler’s door to spend another week there, immobile in his own waste, before the guards, mocking him all the way, would move him to the pretrial detention facility. That’s what Palych meant when he told me that things could be made worse, but I didn’t have the hindsight of two years at that moment.

Palych got what he wanted: the immediate impression he made on me was radically different from what would encounter a few weeks later. Another reason hews initially decent to people was to give them only mild things to report should they get lucky and be transferred out of Isolation quickly. They would never have witnessed the ugly reality of the place.

*****

Of course, it wasn’t just Sergei— who would indeed be returned to the cell half dead— that I could not face that night. And my cellmate, who was still capable of feeling empathy, was not the true object of my anger. I could not face the thoughts of my mother, who had been crying at night for a year while taking care of her elderly parents and who had spent her last cash on food that would not reach me. And of the woman I loved, whom I didn’t have a chance to see before being captured and who was now compelled to wait for me not knowing what I was going through. Nor could I possibly face the wife of the unfortunate man who was beaten to death in the police van, and who was told her husband had gone to Russia and disappeared there. Or of the young woman Palych raped, who had a husband and a young child on the outside. I raged against myself. I hated myself for all this, for being made to know these things. Whom could I tell about this? And how? If I let myself think about all of it, I’d feel torn apart. I wouldn’t last a day. Curled up into a ball under the blanket on my cot, I hid from the rest of the world that so often comes to find prisoners at night.

This “mental separatism,” as I referred to such distancing, was evident in other inmates, too, when they laughed hysterically at the mention of a torn scrotum or sexual violence. Whereas an ordinary person would react to such information with disgust, hatred, or fear, Isolation’s prisoners joked and laughed till they had tears in their eyes. The concept of normalcy became relative; it was impossible to absorb daily torture and abuse on an ordinary person’s terms and not go insane. When the mind cannot process a situation, it begins to normalize terror to preserve itself. This produces the indifference and even irony toward other people’s suffering.

The reverse of this was the sense of obligation one felt with respect to those employees of Isolation that didn’t abuse or torture us but were “just there to do a job,” as some of us put it. I think the underlying psychological chain went like this: when the enemy treated us humanely, we were grateful, and the gratitude produced a sense of indebtedness and guilt about not being able to repay the favor. Many inmates were determined to tell the world about what was happening in Isolation once they were free, but then hesitated because such testimony would harm the one guard who said “Good morning!” instead of cursing or beating them. The distinction between “the good” and “the bad” among our enemies prompted some prisoners to care for the former and hate the latter even more. The more the old “iron door syndrome” dissipated— one that forced every prisoner’s muscles to contract involuntarily whenever the previous administration even touched the lock, because every knock on the cell’s iron door meant a new beating— the stronger the Stockholm syndrome set in.

However, our extreme circumstances did not warp our emotional response all the time. Sometimes people would respond reasonably: they’d cry. Among the men in Isolation, I only witnessed crying— actual desperate sobbing—twice. Moans and cries of pain were as common as fresh burns and broken ribs, but to see a stoic man breakdown like that was much harder.

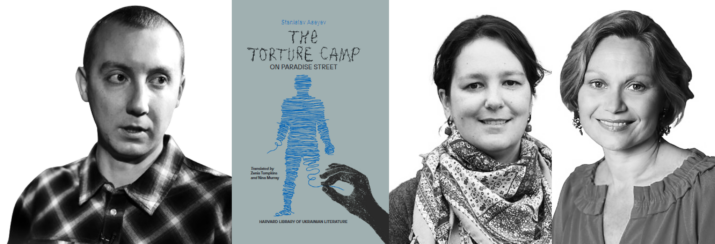

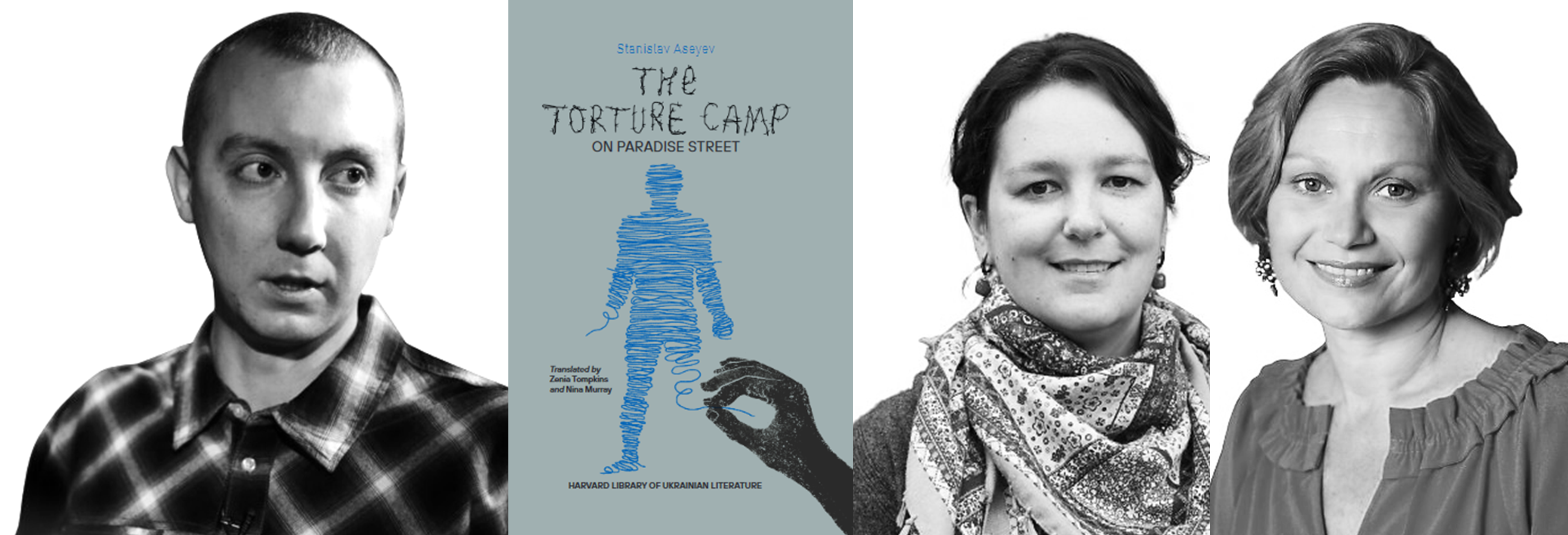

Stanislav Aseyev is an award-winning Ukrainian journalist and writer. In addition to two books recounting his experience under Russian occupation in Ukraine’s east, he is the author of a collection of poetry, a play, and a novel. Under the pen name Stanislav

Vasin, he published short reports in the Ukrainian press about the situation on the ground following the outbreak of Russian-sponsored military hostilities in Donbas. Arrested and unlawfully imprisoned by separatist militia forces for “extremism” and “spying,” Aseyev was held captive and subjected to mistreatment and intermittent torture for over two and a half years.

Zenia Tompkins is an American literary translator and founder of The Tompkins Agency for Ukrainian Literature in Translation (TAULT,www.tault.org), a nonprofit literary agency and translation house dedicated to promoting contemporary Ukrainian literature in the Anglophone world.

Nina Murray is a poet and an award-winning translator of Ukrainian literature, including works by Oksana Zabuzhko, Oksana Lutsyshyna, Serhiy Zhadan, and Lesia Ukrainka. She is the author of several poetry collections and a career member of the US Foreign Service.

Originally published as Stanislav Aseyev, THE TORTURE CAMP ON PARADISE STREET by the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University. Copyright © 2023 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Reproduced by permission.

Non-English title: «Світлий шлях»: історія одного концтабору.

Photo of Zenia Tompkins by Deirdre Tasler | Photo of Stanislav Aseyev by Dmytro Sierhieiev, courtesy of Izolyatsia Foundation.

Published on June 17, 2024.