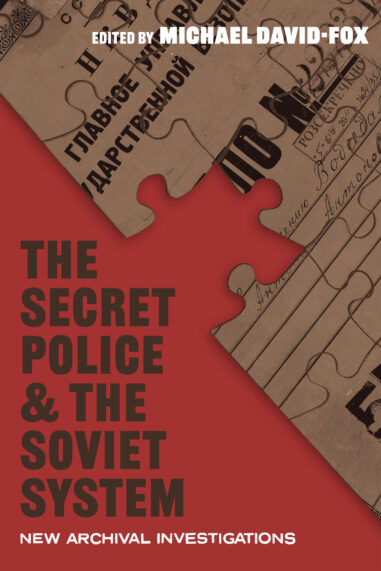

The Secret Police and the Soviet System: New Archival Investigations Edited by Michael David-Fox

The fascinating collection The Secret Police and the Soviet System, edited by Michael David-Fox, introduces thirteen essays illuminating the multifaceted role of the political police as a historical actor throughout the history of the USSR. The book, which is roughly chronologically structured, addresses major historiographical questions, including that on the relationship between the purges of 1937-1938 and the Great Patriotic War, the transition away from Stalinism, and the nature of de-Stalinization, using (more or less) newly opened political police archives from across the former Soviet space. Developed from papers presented at the 2020 webinar “Political Police and the Soviet System,” this edited volume gives an overview of several trends in political policing studies. Michael David-Fox identifies four discussions to which his work contributes: the internal institutional evolution of the political police, the best and worst practices of this institution (for instance in shaping the conception of state enemies), the role of the political police as a cultural and ideological actor, and the historiographical relevance of perpetrator studies to research on the Soviet political police. The book has two purposes. It is intended to address the influence the opening of political police archives after the “archival revolution” has had on the field of policing studies; it is also meant to present research on various existing and new themes in policing studies. Among others, these themes include the identities and internal institutional culture of chekists (an internal term designating political police officers that comes from the original name of the organization—the Extraordinary Commission, i.e., the “ChK”) and “secret police aesthetics.”

Two of the chapters reveal especially clearly the new possibilities the archival revolution opened after the fall of the USSR in 1991. Mikhail Nakonechnyi and Edward Cohn both examine the realities behind infamous but difficult-to-study political police practices, as reflected in the political police files. Nakonechnyi does so by examining the GULAG statistics that have been used to assess the lethality of the prison camp in comparison to that of other forced labor systems. While many historians believe these statistics to be fairly accurate overall, some eyewitnesses disagree. Nakonechnyi argues that comparing different types of statistical records and following intra-institutional controversies helps historians discover the intentionality and mechanisms behind the concealment of high mortality rates in the GULAG. In his chapter, Ed Cohn, like Nakonechnyi, reads between the lines of political police documents to better understand the post-war policing practice of engaging in prophylactic conversations with citizens. The infamous “Profilaktika,” which was developed supposedly as part of a movement away from the violent and repressive policing of the Stalinist period, was, according to Cohn, of dubious efficacy, because the political police lacked adequate means to uncover whether such conversations influenced individuals in the long term, in particular when people were not recidivists, had deep anti-Soviet convictions, or worked in professions that placed them in opposition to the Soviet state (e.g., prostitutes). The studies by Cohn and Nakonechnyi reveal how a critical re-examination of political police documents can shed new light on well-known practices of the political police.

In addition to providing new methodological insights, The Secret Police and the Soviet System contributes to several ongoing debates on the internal culture and institutional transformation of the political police. In particular, the book addresses the chekist mentality—or even “subjectivity.” In their contribution on Stalinist perpetrators, Timothy Blauvelt and David Jishkariani argue that the idea of “ordinary men” does not translate well to the context of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs, whose officers were elite members of society. These officers were not confident in their status, and many of them had unsavory personal and social backgrounds or connections. Thus, their absorption of the state’s ideology, self-perception, and vision of the enemy were accompanied by a fear of being ousted as impostors, leading them to participate more fully in the violence perpetrated on their fellow citizens or colleagues. In the same vein, Molly Pucci’s chapter focuses on the deeply imperfect way Soviet advisors transferred the Soviet experience to their colleagues in the near abroad. Although she does not use the word “subjectivity,” she nevertheless discusses how a shared institutional culture and mentality crystalized among political police officers, also explaining how Soviet advisors approached their activities abroad by drawing on their shared experiences in the USSR, especially during the purges of 1937-1938 and the war. Sometimes, their preconceptions blinded them to the nuances of the local contexts in which they operated. Finally, Joshua Sanborn argues, in his chapter, that established habits of chekist work foiled the attempts of the KGB to computerize its databases. Officers’ possessiveness of the information they obtained and consequent reluctance to enter it into digital systems reveal that internal practices of secrecy ingrained in political police institutional culture could push back even on those initiatives triggered at the highest level of leadership. The book’s contributors do not use the word “subjectivity”—aside from Blauvelt and Jishkariani—but all the chapters reveal the existence of a chekist mentality and praxis that fundamentally shaped the work of the police institution and the experiences of its employees. This question has been explored in other recent works such as Lynne Viola’s Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial,[1] with which Blauvelt and Jishkariani’s chapter is in dialogue, and Alexandra Sukalo’s dissertation on the training and work of political police operative officers between 1945 and 1953.[2]

The Secret Police and the Soviet System also draws on and contributes to trends in such disciplines as cultural studies and literature. In particular, several chapters use the concept of “police aesthetics” to explain the meaning of secrecy in Soviet society and, thus, the experience of both officers and ordinary people.[3] In their respective contributions, Cristina Vatulescu and Tatiana Vagramenko explore how images produced by or with the heavy participation of the police created and reinforced narratives about various “enemies,” leading to the suppression of those enemies’ views of themselves and of their activities. Vagramenko specifically describes how certain religious groups resisted being photographed by the police, using the concept of “political police aesthetics” to highlight how they viewed the political police and its work and explaining how these aesthetics were a factor in the way they resisted the police. Acts such as singing while standing for a headshot could be considered part of a symbolic protest against the power the political police had to mold individuals into “enemies” linked to vast conspiracies.

The edited collection serves as an introduction to the state of the field in Soviet political policing studies, thus also as a starting point for further exploration. Additionally, the book points to the potential of comparative analysis in research on the history of the political police; for example, comparing the situation in countries within and outside the Warsaw Pact could help better grasp how policing organs created on the Soviet model addressed different challenges across eastern and central Europe. Moreover, the volume overall prompts further questions about how political police statistics reflect the perceived and actual state of operative and investigative work. As a snapshot of contemporaneous research, the book also opens a broader discussion on how chekists themselves, at all levels of the hierarchy, understood the history and changing practices of their institution, a topic which has been somewhat understudied for the period following the Great Patriotic War. The Secret Police and the Soviet System is thus an essential read for any junior scholar interested in the topic. At a time when the archival landscape in eastern Europe is rapidly changing, it is especially important to take stock of the work scholars have achieved and to devise ways to develop the field under these new conditions.

Sophia Kalashnikova Horowitz is a PhD candidate at Harvard University. She is currently working on a dissertation titled “The Secret Lives of Soviet Informers under Stalin and Khrushchev, 1937-1965” on the social and institutional history of informing to the Soviet political police.

The Secret Police and the Soviet System: New Archival Investigations

Edited by Michael David-Fox

Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press

Hardcover / 432 pages / 2023

ISBN: 0822948028

[1] Viola, Lynne. Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial : Scenes from the Great Terror in Soviet Ukraine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

[2] Sukalo, Alexandra. “The Soviet Political Police: Establishment, Training, and Operations in the Soviet Republics, 1918-1953.” PhD diss. Stanford University, 2021.

[3] Vatulescu, Cristina. Police Aesthetics: Literature, Film, and the Secret Police in Soviet Times. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.

Published on June 17, 2024.