Translated from the French by Tess Lewis.

April

Ferocious mistral. Mont Ventoux hidden in a pink-grey mist.

April

Beautiful days.

This morning, the snow on Mont Ventoux gleams in two spots, very low, on the eastern ridge. Foliage glistens like water in the large green patch of the ‘château’s’ meadow. These greens, a bit yellowed and so fresh, of the new leaves. Such beauty seems a challenge or an insult to the heart: the human is so inadequate before this order.

In February, I saw the light plunge its brilliant shaft into this same meadow of vibrant green.

The conifers are dark, immutable columns in this landscape where the oaks are still just a pink haze, a bit more than haze surely: like a layer of earth that is much lighter, less dense than real earth, a haze, but a haze of earth held up by branches, exalted by the trunks; banners, fans, crowns or corollas of pink earth, suspended earth pinker for being suspended, through which we can make out garlands, chains, twists of ivy. While the chestnuts are already an unfathomable abundance of leaves, and the linden and acacia trees are just budding, each species offering another number, another complement of leaves, another nuance. Between noon and four, however, the light is too even, too dull and the tableau frozen.

Beautiful backlight. The walls appear black and the early wheat and new grass are intensely luminous, as if illuminated from within by gold, the yellow of gold. The ploughed fields are black, too. This is the section of the landscape that lies to the west, near the cemetery, the chapel and the ancient marshland—it is a rather large valley, mild, more damp. The Rochecourbière plateau with its oaks and boulders begins at the valley’s edge; and over this plateau is air, a fever of space, a flight.

❧

The wing lifted, turned, was gilded.

Gold on its tip and over it, deep shadows.

It is the hour when air takes flight, when the ground blazes,

When the highest air freezes . . .

❧

White and green pear trees, white and yellow-green cherry trees. The scenery of the western Eautagnes, the blonde willows, the shades of green, its landscape gardens, its golden peaks in the evening.

Still spring: the mixture of cold and heat. Warm gusts in the still frigid air, like rolling balls of yarn. Winds from the west or the south. Shadows passing over the trees, the gardens. Irises, tulips, wallflowers, periwinkles.

The rosebush’s leaves shudder and beat their wings against the wall. The scent of irises.

The trees are already full, the chestnuts’ banners unfurled. I would have liked to surprise their opening and soon it will be too late. Even the oaks are budding.

Those banners trembling against the walls. Today I can picture more clearly the transition from spring to summer in the garden, during which the garden gradually closes in on itself and covers itself, changing into a pavilion or grotto of leaves, whereas in winter everything is open: iron lattice, latticework of bare branches, and the dusty ground, and the stones, with just a few grey plants, lavender, cotton lavender, candytuft. Grey, brown, white, wood, stone, iron, earth. Then the brief moment—March—comes, when pink or white butterflies flutter their wings amidst this bare, elementary matter, a moment of brief fire and light snow as if suspended in the air above the dust; and already the greenery reappears, like a humming that sets in here, then there, following some immutable order. It is the greenery of privets and climbing roses along with that of peach and almond trees, then the persimmon, glossy, almost yellow, then the fig tree. Later still comes the acacia, particularly light and trembling, finally the linden. It’s still not much: the beauty of the rose leaves fluttering against the old warm stones, leaves scarcely heavier than the shadows, and hardly any more distinct, like an unceasing animation against the wall’s ancient calm, like a whispered conversation. But I remember what it will become—especially in May, before the heavy, dry heat—when space closes in and covers itself, bends without ever being weighed down, becomes a house of leaves and flowers, the most beautiful shelter against expansiveness.

❧

Speak of a waning power, follow vanished poetry. Fidelity and defiance.

❧

Mountain: ermine in flight.

Frozen, snapping banner.

River: daughter of the arc, stemming from the arc towards rings of the sea’s target. The arc is its source.

❧

The desperate felicity of words, desperate defence of the impossible, of that which everything contradicts, denies, undermines or destroys. At every moment, it’s like the

first and last word, the first and last poem, confounded, solemn, improbable or without force, stubborn fragility, persistent fountain; at night once more it sounds against death, cowardice, stupidity; once more its freshness, its clarity against drivel. Once more the unsheathed star.

❧

Now I side with the unattainable

and pledge once more my ageing hand

to the ever-receding target,

to arrows so fleet they glow with golden fire.

Dying, I now speak only for the gold

and, almost nothing, for the immensity of space,

and, wretched dirt, for the raptors’ spheres,

and, straw, for the strongest wind and fire.

Everything breaks, everything becomes wrinkled,

everything is defeated,

we are born to see others fall and bleed,

he flatters who calls us wisps,

but as I crumble, I will make daylight reign.

❧

Again, this evening, once more, desperate and vain talk

directed against that which feeds it,

words born of death against death,

engendered and undone by death,

an endless, impotent buzzing of flies

against flesh’s decay

and day’s overarching splendour.

❧

A conversation of leaves on the stone wall,

we won’t speak in the sunlight much longer,

Our backs against the warm slab, we laugh

then nothing remains but the dark or the name of

the leaf . . .

April

Monument dedicated to the impossible. The best of oneself given in complete loss to something one will never obtain.

Flowers of peach trees offered up to the bees of fire.

No more detours: return instead like a whip to the target. One’s look, one’s word like a whip.

From the coals of night, on the night’s black branches, this blossoming, this pink grace, and soon after the humming bees of day.

Let all who wish to, recognize in this crest what is most beautiful in the world—what man discovers when insomnia wakes him at the end of the night—and what later lifts him up, like a wing, above himself.

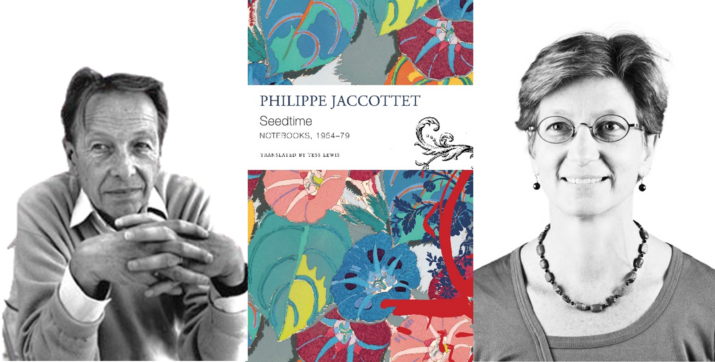

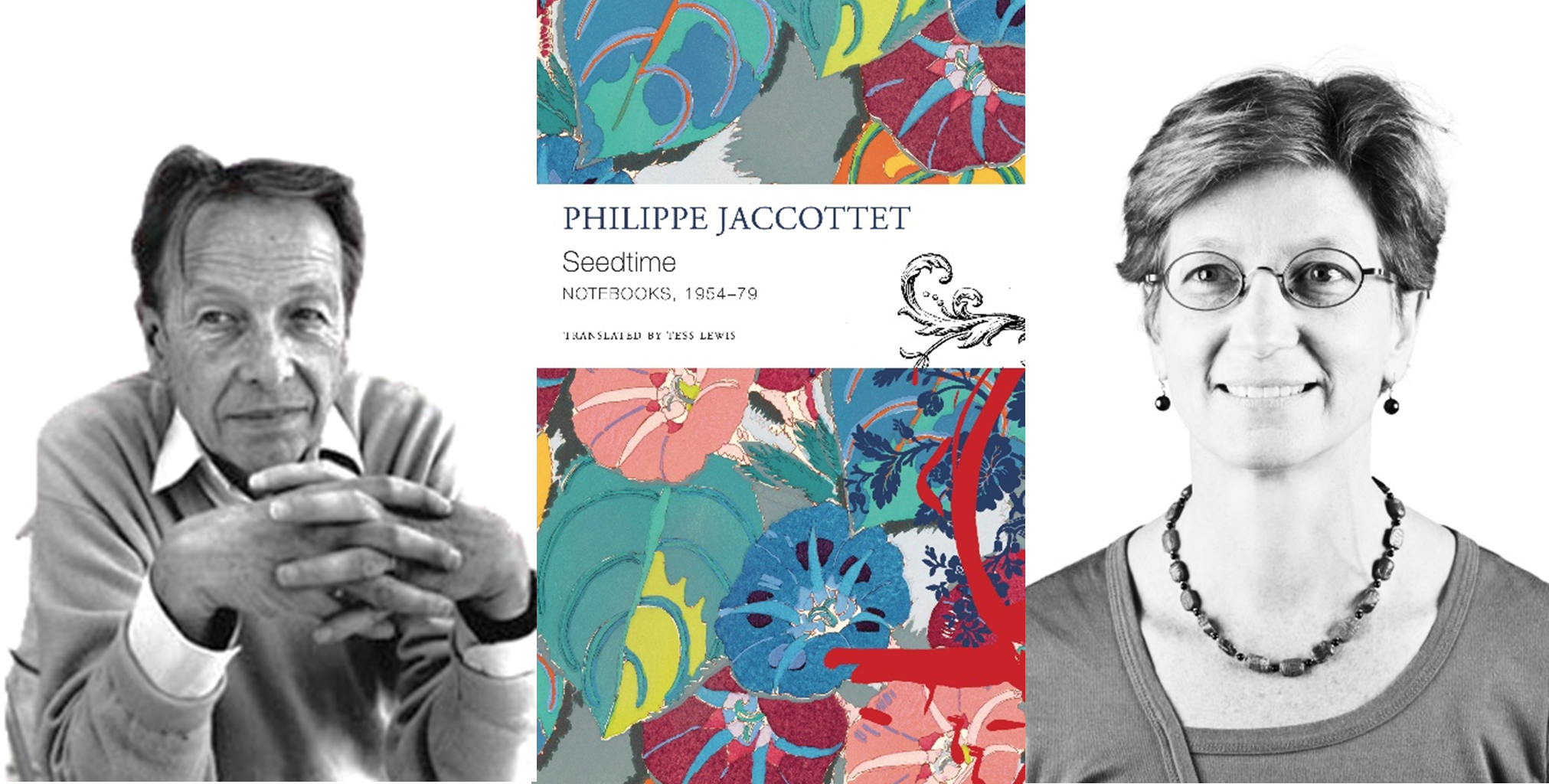

Philippe Jaccottet (1925–2021) is a celebrated European poet who was born in Switzerland and was a long-time resident of France, In 2014, Jaccottet’s collected writings were published in Gallimard’s prestigious Pléiade series. He has been awarded several European literary prizes, including the Grand Prix Suisse de littérature, the highest Swiss literary distinction.

Tess Lewis has translated numerous works from French and German, including works by Peter Handke, Jean-Luc Benoziglio, Klaus Merz, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, and Pascal Bruckner.

This excerpt from SEEDTIME NOTEBOOKS, 1954-79 was published by permission of Seagull Books. Copyright @ Philippe Jaccottet, 1984. English translation copyright @ Tess Lewis, 2013, 2024.

Photo Philippe Jaccottet: