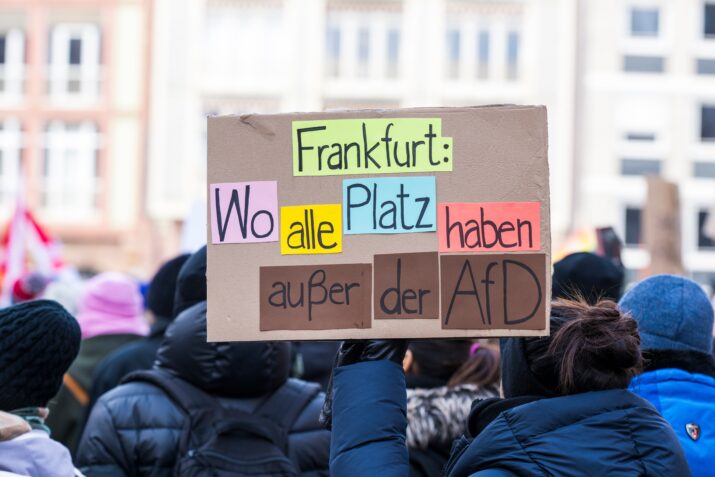

There is a lot at stake in 2024. Elections will be held in the US; the European Parliament will be reconstituted; and, in some countries, several key elections will be held at the regional and local levels. These parallel events make 2024 a potentially transformative election year in many countries—with an uncertain outcome for the tectonics and stability of European societies. In Germany, elections will be held three times this year in many regions: local and European elections are scheduled for May and June, while new state governments will be elected in September in the three eastern German Länder (states) of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia. These elections are taking place against a backdrop of uncertain majorities and major concerns about electoral outcome. These concerns have been expressed during large, ongoing nationwide protests against the far-right party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), since mid-January, in which several million people have take part.[1] The protests have been directed against the radicalization of the party, which was founded in 2013 and is now the strongest political force in the regions of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), known in German discourse as East Germany[2] (Weisskircher 2020; León and Scantamburlo 2023). The protests were prompted by reports of a secret meeting between members of the AfD, the WerteUnion, and the right-wing identitarian movement, where the forcible deportation of migrants, including German citizens, was discussed. These revelations made it clear to a broader public how deeply the populist radical right party AfD is involved in the nationalist-neo-Nazi scene and how profoundly disruptive and radical its fantasies of transforming German society are. Thus, in the context of the AfD’s predicted electoral success—at least in state elections in the eastern part of Germany—the threat has suddenly assumed sharp and very specific contours for many people.

Although the AfD so far has been excluded from participation in government, its status as a pariah belies its strength and influence in contemporary German politics. As a result, three-party alliances across political camps, while previously unusual in Germany, have had to be formed more and more frequently (Bäck, Debus, and Imre 2022). The probability that minority governments could emerge is increasing and with it the risk that new actors, though excluded from power before, could now exert increasing influence on governmental action (Decker, Ruhose, and Adorf 2023).

Since the beginning of 2024, the German political situation has become even more complicated because of the founding of two new parties: the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – for Reason and Justice (BSW), named for the former co-chair of The Left´s parliamentary group in the Bundestag, and the WerteUnion, which emerged from the right-wing conservative circles of the CDU and is prominently led by Hans-Georg Maaßen. Neither party rules out cooperation with the AfD, and both parties’ platforms reflect shifts in the German political discourse—but even more so in the leadership style and openly radical stances of their founders. A common explanation for such new formations is that new parties fill a gap in representation in the political system (Kortmann, Stecker, and Weiß 2019). A different or complementary interpretation would be that the heads of these new parties have themselves for years played a key role in shifting the political discourse and normalizing populist, radical, right-wing political content. These parties can act either as “bridge builders” between left-wing and right-wing authoritarian milieus, as Wagenknecht’s party has done, or as “brave witnesses” to and “whistle blowers” for an alleged quasi-dictatorial restructuring of German society, as Maaßen’s party has done. These developments are part of a global trend to use far-right sentiments to shape politics. Debates such as those on migration in Germany in 2015, or events such as the election of President Trump in the US and Brexit have been catalysts for the spread of far-right politics. As a result, transnational far-right communities influence each other’s rhetoric and strategies (Ramos and Torres 2020).

The staging of dissidence: resonances and projections

A look back at 2019 reveals that state elections took place in Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia that year. Before these elections, tension was high because forecasts in Saxony saw the AfD as the strongest party. Even then, there was talk of “fateful elections.” Three-party governments were formed with difficulty in Brandenburg and Saxony, and a three-party minority government even arose in Thuringia. However, although the AfD made a strong showing, it was excluded from these governments at the time.

In the run-up to the 2019 elections, we conducted group discussions in small and medium-sized towns in Saxony as part of our project, “The contested legacy of 1989.”[3] On one occasion, we went to an old textile workers’ town in the south of Saxony. We met our interviewees in the back room of a pub, where they usually hold their group meetings. They were politically engaged people, mostly pensioners, mostly men, and some of them had been active in the opposition in the fall of 1989. Material from the initiatives they were currently involved in was displayed on a large table, for example informational brochures on the alleged dangers of 5G mobile phone technology. Such initiatives echoed topics that were then trending on Facebook and YouTube. But there was also a flyer stating that a nationally known former East German civil rights activist and former CDU member, Vera Lengsfeld, who had been active in the New Right for several years, was to be honored by the group with a “Freedom Prize.” The group celebrated Lengsfeld for her opposition to the GDR as well as to the “Merkel CDU.”[4]

The participants had much to say during a three-hour group interview. They spoke about the fall of the East German government in 1989, the present need to stand up again, democracy as a “dictatorship,” Julian Assange, secret NATO troop movements, education policy, the economy, Germany’s political reunification, the Antifa (antifascist activists), Germany as an “appendage of the US,” right-wing extremists in the city, and post-1989 grievances and disappointments. During a break, the local AfD state parliamentary candidate entered the room, greeted everyone in a friendly manner, and asked participants to canvass their friends and relatives. Nobody in the room had any qualms about contact with the AfD. In general, the group alleged that mainstream society had only a very one-sided, empty understanding of right-wing extremism. According to them, anyone who “castigates the failure of politicians” is considered a right-wing extremist, and therefore the accusation of right-wing extremism only serves the governing parties, which “need an enemy to distract from their own failed policies.” To illustrate this strategy of dealing with political opponents, they quoted the dismissed President of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), Hans-Georg Maaßen, who had become the key witness to an alleged political practice consisting of persecution, defamation, and stigmatization. In his speeches, Maaßen has presented himself as an outlaw in his own party—the CDU—because he says out loud what all covertly believe to be true. “Conspiracy theory—that’s what the secret service brought into play here to immediately stigmatize anyone who, in a certain way, like you now, points something out.” Several of those who participated in our study cited other examples, as shown in the following excerpt:

There are critics in every party. With the Greens, it’s Palmer. In the SPD, it’s Sarrazin; in the Left, it’s Sahra Wagenknecht. And now it’s Maaßen in the CDU. These are actually people who—let me say—have understood…Critics, you could say. So these are objectivists (non-partisans?) who also show their own party to be out of order. Realists…So what’s next? A motion to exclude. But that’s not normal either. You must do it, I say, if they no longer tolerate constructive criticism from their own party…Then it won’t be long before they expel us all from the country.

The mention of these politicians had one main function for the interviewees, which is to self-identify as victims and martyrs for “the truth.” They saw themselves as they portrayed these politicians, i.e., as “deviants” doing something risky and highly subversive—namely saying the outrageous. They fantasized about being exiled themselves but “Where to? Nobody will take us.” Cynically alluding to global refugee migratory flows, a participant added that “There’s room in various countries.”

Moreover, these politicians were not invoked arbitrarily, as they represent their party’s internal dissidents, having heroically staged their criticism of their own party as a rebellious act of resistance and become outcast and ostracized as a result. This victimization regularly stands in sharp contrast to the wide circulation and financial success of these dissidents’ provocative bestsellers and the public attention these books receive. This tension makes these politicians both attractive and highly questionable as political influencers. For a long time, Soviet opposition figures such as Andrei Sakharov or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who risked state repression and persecution for speaking out, were labeled dissidents. Today, this label is inappropriately applied to individuals involved in public interventions that are low-risk but entail a high pay-off. Today in Germany, Thilo Sarrazin, Hans-Georg Maaßen, and Sahra Wagenknecht—under the borrowed mantle of party dissidence—are key figures in a discursive shift to the right, which they not only exemplify but have themselves helped shape over nearly 15 years. Two of them—Hans-Georg Maaßen and Sahra Wagenknecht—have even founded their own parties.

Thilo Sarrazin, Hans-Georg Maaßen, and Sahra Wagenknecht

Sarrazin was Senator for Finance in Berlin between 2002 and 2009 and a member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank. He was a member of the SPD until he was expelled in 2020. Before his expulsion, he had worked in various ministries since the 1970s; and the high profile of these various offices guaranteed him a high level of public scrutiny. Excerpts from his book Deutschland schafft sich ab (Germany abolishes itself) (2010), which sold millions of copies, were published ahead of print in leading German media outlets and popularized central political tropes of right-wing populism long before the AfD was even founded. In many ways, Sarrazin provided the vocabulary for the subsequent rightward shift in German political discourse. His racist warnings of a demographic “overwhelming” that would make Germans “a minority in a predominantly Muslim country with a mixed, predominantly Turkish, Arab, and African population” (Sarrazin 2010, 360) made topoi of the extreme right socially acceptable, as it supported the idea of repopulation or “great exchange,” an apocalyptic critique of the present and social Darwinist ideas. Sarrazin referred to the book “The Bell Curve” by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray to prove that a biologically inferior underclass—”Muslim immigrants,” instead of the African-Americans Herrnstein and Murray wrote about— posed a threat to German society (Gilman 2012, 52). In his subsequent books, Sarrazin further spelled out such topoi, helping to popularize and mainstream Euroscepticism (2012), the distorted image of a “dictatorship of political correctness”(2014), and the populists’ juxtaposition of reason and ideology, rendering the respective political positions into caricatures (2022). Using his reach and former membership in Germany’s political elite, Sarrazin paved the way for the founding of the AfD in 2013 and for the wave of protests by members of the Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA) movement in 2014; he thus stands “as a kind of spiritus rector of the AfD” (Decker 2016, 15). However, as influential as he was at that time, Sarrazin had remained a loner who shied away from involving himself with the populist party. But he became a role model for populist-staged dissidence, as the next example shows.

At a time when the political shift to the right in Germany was becoming visible when observing influential parties (as exemplified by the rise of the AfD) and protests (as those organized by PEGIDA), CDU member Hans Georg Maaßen was nothing less than the President of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV). However, his actions while holding this position were so controversial that he was dismissed in 2018. Before that, in 2015, he had advised the AfD on how it could avoid being monitored by the BfV. In 2018, when riots and far-right protests in the eastern city of Chemnitz in Saxony made international headlines, Maaßen denied that foreigners had been hunted by right-wing extremists and denounced video evidence of the protests as false information spread by the media and politicians. In 2019, he joined the WerteUnion association (not yet a political party at the time), which promotes a right-wing conservative profile within the CDU. Since then, he has repeatedly publicly advocated extreme right-wing positions; and since 2024, he has himself been the subject of surveillance by the BfV. Proponents of the extreme right consider Maaßen as one of their own and the fact that he held a key position within state institutions as part of their “long march through the institutions,” describing him “as a beacon of the radical right-wing movement” (Fernholz 2022, 24). Moreover, there are considerable overlaps between the WerteUnion and the AfD. At the beginning of 2024, Maaßen finally declared his intention to transform the WerteUnion into a formal political party and to participate in elections in three Länder (Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia).

The case of Sahra Wagenknecht is more complicated than Sarrazin’s and Maaßen´s. For a long time, she was one of the best-known and most popular politicians in the Left Party. She staged her internal opposition directly from the top of the party, as she was simultaneously the party’s figurehead and a public figure who openly deviated from the party line. Above all, she has taken anti-migration positions since 2015 and later promoted pro-Russian and Eurosceptic narratives. Thus, rumors of Wagenknecht’s expulsion from the Left Party or even a split in the party have been in the air for a very long time. And for just as long, there have been advances toward her from the extreme right, which sees Wagenknecht as a fellow partner and praises her influential outsider status within the Left Party. In 2022, she graced the cover of the extreme right-wing Compact magazine that bore the headline, “The best chancellor: a candidate for the left and right.” Consequently in 2023, AfD politician Björn Höcke invited her to join his party. These expressions of support are more than simple right-wing projections of a Querfront (cross-front) between left and right, as they also have a substantive foundation. Wagenknecht’s positions have changed drastically from left to nationalist in recent years: once a supporter of Marxism and Stalinism, she now lauds the middle class, supports a social market economy, and urges the strict isolation of Germany on the global stage (Veiglhuber and Weber 2022). With her harsh criticism of the Left Party as a mere “lifestyle” left-wing party (Wagenknecht 2021), Wagenknecht deploys the full spectrum of culture-warrior arguments used by other polarization entrepreneurs in Europe and North America.[5] According to this world view, migrants and gender stereotyping are more dangerous than the AfD, and the Greens represent—logically—the “most dangerous party” in Germany. The recent internal conflicts in the Left Party culminated in Wagenknecht and ten other members of the Bundestag leaving the party and founding the “Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – for Reason and Justice” (BSW). The aim of this new formation is to run in the European elections and the three Länder elections in 2024. The emergence of the WerteUnion and BSW has had consequences in terms of the normalization and resonance of anti-establishment populism and the rise of Euroscepticism. It has also influenced the debate on whether politicians should cooperate with the AfD or whether that party should be excluded from the political arena.

Constellations of destabilization?

Forecasts about the strength of the WerteUnion and BSW are currently still speculative and polls’ results have been disparate. The agenda of the WerteUnion differs little from that of the AfD. The goals of the WerteUnion’s chairman, Maaßen, are hardly less radical and conspiratorial than those of the AfD. For instance, when Angela Merkel was chancellor, Maaßen claimed that she was “Sovietizing Germany” and that the state’s migration policy was a controlled process deliberately diluting an ethnically German (white) population. It is therefore questionable whether the WerteUnion can achieve any significant success in view of its many overlaps with the AfD. However, Maaßen’s impact has been more discursive than indicative of a realistic chance in elections, even if, as a renegade who headed one of the most powerful institutions in German security policy, his words still carry weight. He has nevertheless relied on this reputation to mainstream the far-right and delegitimize a firewall (cordon sanitaire) against the AfD.

The situation of the BSW is quite different from that of the WerteUnion. Wagenknecht is regarded as a politician who can build bridges between right- and left-wing milieus. Political scientists categorize her new party as “left-authoritarian,” (Wagner et al. 2023, 622) or as a “centrist anti-establishment party,”[6] as she combines mainstream and left-wing economic positions with right-wing rhetoric about culture wars and advances Eurosceptic and pro-Russian foreign policy positions. Current analyses of voters’ intent show that the BSW has greater potential among supporters of the AfD than among supporters of the Left Party (Wagner et al. 2023). In election forecasts, however, the approval rate for Wagenknecht’s party fluctuates dramatically. For example, in Thuringia, voting intentions in the upcoming Länder elections range between 4 percent and 17 percent.[7] In the European elections, but also in the Länder elections, the BSW has a good chance of success.

On the one hand, the BSW could damage the AfD more than other parties could. On the other hand, by entering the parliaments of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia, the BSW could render forming coalitions extremely complicated or impossible and could even make it possible for the AfD to exert influence if only minority governments become possible. Both the WerteUnion and the BSW are populist anti-establishment parties, whose candidates can hope for a substantive response from voters, especially in eastern Germany. What these two parties have in common is that they do not rule out cooperation with the AfD.[8] This is worrisome, to say the least, as 2024 will perhaps be the most important and groundbreaking year in East Germany since 1989/90 and will determine whether the political shift to the right can still be halted and tipping points in democratic culture prevented. This rationale also applies to the elections to the European Parliament, in which a shift in the balance of power to anti-European populist parties is expected.[9] The two new parties are already having one profound effect: the debates about minority governments and about distancing from or cooperation with the AfD has become more prominent. It is the CDU, however, that is playing a decisive role in this matter. The results of the last state elections in 2019

have caused particular dissatisfaction within the centre-right CDU, with some of its most conservative figures pushing for an openness towards AfD as a coalition partner. If a post-Merkel CDU should at some point decide to cooperate with AfD, this is likely to happen in eastern Germany first—perhaps with important consequences, not only for German, but also European politics (Weisskircher 2020, 621).

However, electoral success is not automatic for either the WerteUnion or the BSW, as it is simpler to found a new party than it is to build organizational party structures. And even if many people, such as the group in our study, identify with Maaßen and Wagenknecht as rebellious dissident politicians, it is uncertain whether they will vote for them.

Alexander Leistner is project leader for the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) research network “The contested legacy of 1989” and the taskforce “Ways across the country – democracy in transforming landscapes” (Volkswagen Foundation) at the Institute for the Study of Culture (University of Leipzig).

References

Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Michael Imre. 2024. “Populist radical parties, pariahs, and coalition bargaining delays.” Party Politics, 30(1): 96-107.

Decker, Frank. 2016. “Die ‘Alternative für Deutschland’ aus der vergleichenden Sicht der Parteienforschung.” In Alexander Häusler, ed. Die Alternative für Deutschland, VS Verlag, 7–23.

Decker, Frank, Fedor Ruhose, and Philipp Adorf. 2023. “The AfD’s Influence on Germany’s Coalition Landscape: Obstacle or Opportunity for the Center-right?” In Manès Weisskircher ed. Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics. Routledge, 205–219.

Fernholz, Tobias. 2022. Die rechtsradikale Bewegung und ihr digitaler Kampf um Identität. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Gilman, Sander L. 2012. “Thilo Sarrazin and the Politics of Race in the Twenty-First Century.” New German Critique: 117, 47–59.

Kortmann, Matthias, Christian Stecker, and Tobias Weiß. 2019. “Filling a representation Gap? How populist and mainstream parties address Muslim immigration and the role of islam.” Representation, 55(4): 435–456.

León, Sandra, and Matthias Scantamburlo. 2023. “Right-wing populism and territorial party competition: The case of the Alternative for Germany.” Party Politics, 29(6): 1051–1062.

Ramos, Jennifer M. and Priscilla Torres. 2020. “The Right Transmission: Understanding Global Diffusion of the Far-Right”, Populism 3(1): 87–120.

Sarrazin, Thilo. 2010. Deutschland schafft sich ab: Wie wir unser Land aufs Spiel setzen. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Sarrazin, Thilo. 2012. Europa braucht den Euro nicht. Wie uns politisches Wunschdenken in die Krise geführt hat. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt

Sarrazin, Thilo. 2014. Der neue Tugendterror. Über die Grenzen der Meinungsfreiheit in Deutschland. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt

Sarrazin, Thilo. 2022. Die Vernunft und ihre Feinde: Irrtümer und Illusionen ideologischen Denkens. Langen Müller Verlag.

Veiglhuber, Wolfgang, and Klaus Weber. eds. 2022. Wagenknecht. Nationale Sitten & Schicksalsgemeinschaft. Gestalten der Faschisierung 2. Argument.

Wagenknecht, Sahra. 2021. Die Selbstgerechten. Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt. Campus.

Wagner, Sarah, L. Constantin Wurthmann, and Jan Philipp Thomeczek. 2023. “Bridging Left and Right? How Sahra Wagenknecht Could Change the German Party Landscape.” Political Quarterly 64: 621–636.

Weisskircher, Manès. 2020. “The Strength of Far-Right AfD in Eastern Germany: The East-West Divide and the Multiple Causes behind ‘Populism’.” The Political Quarterly, 91: 614–622.

[1] https://taz.de/Analyse-der-Demos-gegen-Rechtsextreme/!5995645/

[2] The distinction between eastern and western Germany refers to the east-west divide that has persisted since reunification, both in terms of the economic situation and in terms of voting patterns and political attitudes.

[4] “For several years, Vera Lengsfeld has publicly criticized the policies of the German chancellor and, in her work as a freelance author, has stood up for the freedom of opinion and freedom of the press and warned against the undermining of the constitutional state, even accepting personal disadvantages and hostility” (excerpt from the group’s laudatory speech).

[5] https://www.socialeurope.eu/trigger-points-and-the-polarisation-entrepreneurs

[6] https://www.rosalux.de/en/news/id/51574/after-the-split-in-die-linke-the-rise-of-anti-establishment-centrism

[7] https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/sahra-wagenknecht-massive-spanne-bei-waehlerpotenzial-fuer-bsw-in-thueringen-a-508ccd35-f28a-47eb-947f-521788097c7d

[8] https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/wagenknecht-laesst-abstimmungen-mit-der-afd-offen-100.html

[9] https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-sharp-right-turn-a-forecast-for-the-2024-european-parliament-elections/

Image: Shutterstock | Frankfurt am Main, Germany – January 20, 2024: Protest against AfD – Alternative For Germany (German: Alternative für Deutschland, AfD)

Published on April 15, 2024.