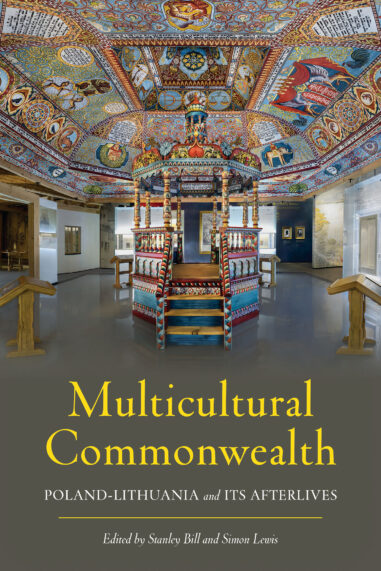

Multicultural Commonwealth: Poland-Lithuania and Its Afterlives Edited by Stanley Bill and Simon Lewis

A multicultural Poland-Lithuania or a composite kingdom of estates and serfs?

A multicultural Poland-Lithuania or a composite kingdom of estates and serfs?

The Commonwealth of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania used to be a composite realm and elective monarchy, extending from today’s Estonia in the north to Moldova in the south. Briefly known as Poland-Lithuania, the polity remains largely unknown in Western academia, like most of Central Europe. But the situation is gradually changing. Editors of Multicultural Commonwealth: Poland-Lithuania and Its Afterlives, Stanley Bill and Simon Lewis, represent a new generation of anglophone scholars who contribute saliently to the field. Obstacles remain, such as the politicization of history in Poland under the authoritarian rule of the Law and Justice party (2015-2023). In Central Europe, it has been the scholarly norm to research national pasts through the dominant lens of national historiography since the nineteenth century. What results is not a dispassionate comprehension of the past but an anachronistic national master narrative that extols each nation’s “grandeur” or “golden age,” which is taught in schools to “explain” how the “millennium-old” stateless nations have survived and won back their “stolen” statehood.

The anthology under review provides an analysis of the Commonwealth’s norms and practices in addressing diversity, with an eye to dispelling prevailing myths and fantasies. The volume opens a vista on a polity that was a fixture of European politics and economy for four centuries, also serving as a corrective to the national but anachronistic view held in Poland that Poland-Lithuania was the “First Republic of Poland” (Pierwsza Rzeczpospolita) (Kamusella 2017). Part I—“The Commonwealth in History”—presents counterintuitive explanations on Poland-Lithuania and punctures several myths. In their respective chapters, Karin Friedrich and Richard Butterwick emphasize that religion more than language, was the object of political maneuvering within the estates of nobility, burghers, and clergy and that this maneuvering can only to a limited degree be retroactively interpreted as “multiculturalism.” Yet, although in 1569, 56 percent of the Grand Duchy’s population was non-Catholic (57), by the late eighteenth century “religious unity” (that is, Catholic homogeneity) was pursued as a socio-political basis for the modernization of Poland-Lithuania (144). Paradoxically, from today’s perspective, Tsarina Catherine II, using the potent (Enlightenment) argument of (religious) tolerance, frustrated this program by strengthening the Commonwealth’s pro-Russian Orthodox Church (150).

Besides presenting Jewish ethnoconfessional autonomy in Poland-Lithuania, where the world’s plurality of Jews used to live (29), in her chapter, Magda Teter dispels the nationalist myth that Jews are foreign by emphasizing that Jews there spoke both Yiddish and Polish (40), although they could not become nobles without converting to Catholicism, unlike ennobled Tatars, who were allowed to remain Muslims. However, Dariusz Kołodziejczyk describes in his essay that the status of Muslims was different from that of nobles of other confessions (72), since noble Tatars suffered pogroms at Catholics’ hands (74) and in 1668 a ban was imposed on the construction of new mosques (72). Discussing cross-influences in sacral art and architecture, Olenka Z. Pevny demonstrates in her contribution to the volume that under the Polish-Lithuanian rule Kyiv throve as the unquestioned intellectual center of modernization for the entire Slavo-Romanian Orthodox world (95). In his focus on intellectual history through the prism of early modern cartography and translation studies, Tomasz Grusiecki refreshingly shows that the Neo-Latinate short-hand name of “(European) Sarmatia” for the Commonwealth, as featured on numerous early modern maps (like the current sobriquet of “Poland-Lithuania” in English) was a compromise translation of the composite monarchy’s lengthy and paradoxical name (115). After all, how could a monarch head a “republic” (which is the literal translation of rzeczpospolita)?

The volume’s Part II—“The Commonwealth in Memory”—takes a historiographic take at Geschichtspolitik and national master narratives as pursued and shaped first in the partitioned Polish-Lithuanian lands during the long nineteenth century and later in the post-Commonwealth (postrzeczpospolitowy, postrzplitowy) nation-states. When discussing Polish noble literati’s (neo-colonialist) visions of the Ruthenian lands (or today’s Ukraine), Bill mentions that the founder of Ukrainian historiography, Mykola Kostomarov, was the first writer to consistently employ the ethnonym “Ukrainians” already in the 1840s (170-1). In turn, Rūstis Kamuntavičius analyzes how Belarusian and Lithuanian historians tend to focus on these aspects of the Grand Duchy’s past that retroactively “justify” the posing of this polity as “belonging” exclusively to the Belarusian or Lithuanian nation, as though the single and shared common past could not bifurcate into separate presents (205-219). Through the lens of culture, Lewis showcases a similar quarrel between the dominant Polish national master narrative and that of subaltern (“exoticized”) Belarusia. He opens the discussion with the figure of General Tadeusz Kościuszko, a hero of the American Revolutionary War, who nowadays is seen as an exclusively Polish or Belarusian national hero (220-1). Given the resurfacing of antisemitism as an “argument” of politics under Law and Justice’s authoritarian rule, Magdalena Waligórska, Ina Sorokina, and Alexander Friedman’s joint contribution offers an insightful glance at the difficulties, paradoxes, and successes met by local efforts in acknowledging the Jewish past of three shtetls in today’s post-Holocaust Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine (241-65). Robert Frost’s take on the parallel careers of originally post-Polish-Lithuanian historians Oskar Halecki and Lewis Namier is most illuminating, also given Law and Justice’s vociferous anti-German rhetoric. Originally, German-speaking Austrian Halecki espoused Polishness, while Namier, a Pole of Jewish decent, when faced with fellow nobles’ relentless antisemitism, chose to become a British subject (185).

Sociologist Ewa Nowicka’s concluding chapter sits ill at ease with the rest of the volume. Ostensibly, it takes stock of Poland’s ethnolinguistic minorities (269-70) and reflects on the influx of Ukrainian economic migrants and war refugees, leading to the conclusion that in the future they will constitute the country’s largest minority (287-9). Yet, strangely, the 600,000 to 800,000 Silesians who live in present-day Poland do not get a mention as the country’s largest minority, as evidenced by all the postcommunist censuses. In fact, until recently Warsaw’s position was that the Silesians did not, do not, and cannot exist because Poland’s 2005 Act on National and Ethnic Minorities fails to list them. Refreshingly, the new democratic government promises to support the teaching of the Silesian language in schools and to recognize the Silesians as an ethnic group.

Methodologically, the anthology missed on the chance to probe into the Commonwealth’s “multiculturalism” as it applies to the polity’s contemporaneous socio-political and economic divisions. These divisions appeared among the estates—especially the nobility and burghers— and the non-estate stratum of serfs, who account for the vast majority of the population. In the Commonwealth, in contrast to what the post-Polish-Lithuanian national master narratives maintain, neither religion nor language constituted the main basis for group formation. Instead, the estates and serfdom played this role. Endogamy is one proof of these dynamics. Indeed, marriages across estates or between serfs and the rest of the population were rare and considered morganatic. In fact, irrespective of language or religion, the Commonwealth’s aristocrats (magnates, magnaci) married other European aristocrats; similarly, nobles (szlachta) married within their estate within Poland-Lithuania, while Christian burghers (mieszczaństwo) chose spouses within their respective cities or nearby cities. Finally, serfs (chłopstwo pańszczyźniane) married within the confines of their home village or parish. Contemporary anthropologists have shown that in the early modern period, aristocracy comprised a French-speaking pan-European ethnic group, while nobles formed an all-Commonwealth ethnicity that monopolized the ethnonym “Poles.” Burghers were split into city- or region-based ethnic groups, while serfs were scattered across a myriad of ethnic micro-groups. No serf, even if (somewhat) Polish-speaking and Catholic would have dared to refer to himself or herself as a “Pole.” This ethnonym was strictly reserved for members of Poland-Lithuania’s nobility.

Most histories of Poland-Lithuania, including Bill and Lewis’s volume here, have avoided tackling Inflanty, i.e., the historical provinces of Courland and Livonia—today’s Latvia and southern Estonia. Yet, adding them to the discussion would help flesh out the “multicultural” character of Poland-Lithuania even better. Specialists hardly ever remember that the territories now contained within the Baltic states used to constitute an important corner of the Commonwealth. An improved awareness about the region would connect Poland-Lithuania directly with maritime colonialism and the Transatlantic slave trade. For instance, in the mid-seventeenth century, Courland established two short-lived colonies in Tobago and Gambia (Anderson 1956; Mattiesen 1940), whose history is taught today in Latvian schools as that of “Latvia’s former colonies” (Turlajs 2011, 21). Similarly, the ethnoconfessional (territorial and non-territorial) autonomies of Jews or Armenians in Poland-Lithuania, which are typical only of early modern Central Europe and did not exist in Muscovy (Russia) or Western Europe, could be usefully compared to similar types of autonomies in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire.

My research into language politics leads me to notice that, in contrast to what the book claims, the 1696 law (17) did not in fact ban Ruthenian as an official language in the Grand Duchy. What this regulation forbade was the employment of “Ruthenian” (that is, Cyrillic) letters, effectively leading to the replacement of Ruthenian with Polish in the long run. Yet, until the nineteenth century, many secular and ecclesiastical scribes basically wrote down their (increasingly Polonized) vernacular Ruthenian in Latin (“Polish”) letters, while their attempts at “standard Polish” continued to include many Ruthenian influences (Lisiejčykaŭ 2017). Prior to the modern period of ethnolinguistic nationalisms in Central Europe, scripts—i.e., alphabets, or writing systems—as characteristic of a religion or denomination were only of symbolic value and political importance. For instance, Tatar nobles wrote in Ruthenian using Arabic letters (78-9), while their Armenian counterparts recorded their Turkic vernacular of Kipchak using Armenian letters. This aspect of the politics of script offers itself as a fascinating lane of research into Poland-Lithuania’s practices of “multiculturalism.” Last but not least, I am rather astonished to see that Cyrillic versions of contemporary place-names in Belarusian or Ukrainian have been romanized, while their Yiddish-language counterparts have been left in Hebrew letters (ix-xii, 241-245). Instead, the contributors could have used the Łacinka, since Belarusian is traditionally written in its two national alphabets, namely, Cyrillic and Latin.

Stanley Bill and Simon Lewis’s Multicultural Commonwealth: Poland-Lithuania and Its Afterlives strikes a good balance between detail and overview. Hopefully, this anthology will soon feature on numerous modules’ lists of assigned reading, contributing to a genuine revival of interest in the history of the Commonwealth and all the post-Polish-Lithuanian states (including Israel). It is still to be seen whether Ukrainian refugees and the financial and military involvement of the Western world in Ukraine’s defense against the Russian invaders will meaningfully place Central Europe and the post-Polish-Lithuanian countries into the Western public’s consciousness.

Tomasz Kamusella is a reader of Central and Eastern European history at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. His recent monographs include Ethnic Cleansing during the Cold War (Routledge 2018), Politics and Slavic Languages (Routledge 2021), and Eurasian Empires as Blueprints for Ethiopia (Routledge 2021). His reference Words in Space and Time: A Historical Atlas of Language Politics in Modern Central Europe is available as an open access publication.

References

Anderson, Edgar. 1956 [PhD dissertation]. The Couronians and the West Indies. Chicago IL: University of Chicago.

Kamusella, Tomasz. 2017. The Un-Polish Poland, 1989 and the Illusion of Regained Historical Continuity. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Leszczyński, Adam. 2020. Ludowa historia Polski. Warsaw: W.A.B.

Lisiejčykaŭ, Dzianis. 2017. “Ruskaja” mova mietryčnych knih unijackich cerkvaŭ Vjalikaha Kniastva Litoŭskaha ŭ XVII-XVIII stahoddziach. Biełaruski histaryčny časopis, 6: 13-28.

Mattiesen, Otto Heinz. 1940. Die Kolonial- und Überseepolitik der kurländischen Herzöge im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Rauszer, Michał. 2021. Siła podporządkowanych. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Turlajs, Jānis, ed. 2011. Latvijas vēstures atlants. Riga: Jāņa sēta.

Multicultural Commonwealth: Poland-Lithuania and Its Afterlives

Edited by Stanley Bill and Simon Lewis

Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press

Hardcover / xii + 383 pages / 2023

ISBN: 978-0-8229-4803-2

Published on April 15, 2024.