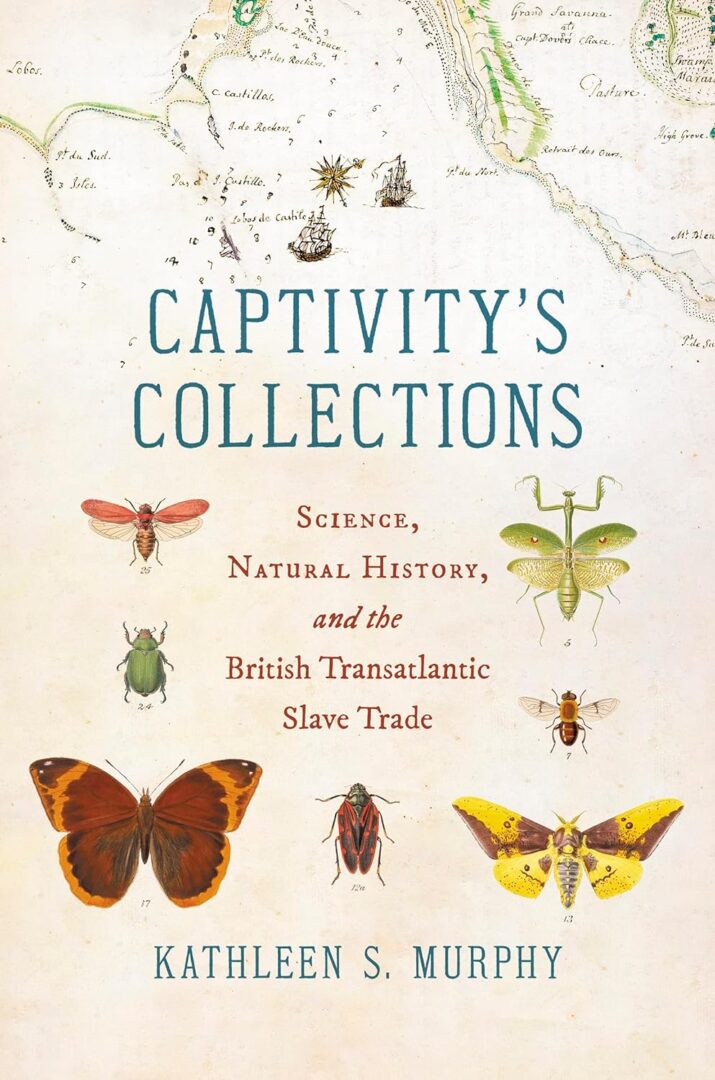

Captivity’s Collections: Science, Natural History, and the British Transatlantic Slave Trade by Kathleen S. Murphy

For several years, I have been prosecuting the idea that plants flourish with or without human witness, even with or without human consciousness. However, it has become increasingly clear that humans and plants have always been entangled. This entanglement of humans and plants is part of a developing concept of research that I have termed Dark Botany.[1] Dark Botany is the method of critically engaging with the violence and extractivism of botanical history. It is a process of accepting the monster in the mirror. This is relevant for those of us who have grown up in colonial settler countries such as Australia, where we have not outrun imperial forms of British control and rapacious neo-colonial “taking.” It is through a Dark Botany lens that Kathleen S. Murphy’s new book, Captivity’s Collections can be read. Murphy is a professor of history at the California Polytechnic State University. Her new book charts the intertwined passages of the eighteenth century British slave trade and the British thirst for commerce, veiled as botanical knowledge. Plants and humans dovetail in this forensically researched book about slave ships and the British puppeteers controlling the narrative behind these voyages. Murphy follows slave-ship surgeons, mariners, and slave traders. She connects these undertakings and persons of interest with the rise of natural history collecting of plants, insects, and animals. Her thesis is that British transatlantic enslavement and the explosion of natural history knowledge were two co-dependent activities. Just as slaves were collected from East Africa, purchased, and transported for economic profit to various places such as the Caribbean, so too were the butterflies, beetles, cashews, fossils, and dolphins collected and transported back to Britain in order to amass knowledge and power.

West Africa was a prized location for European natural history enthusiasts. However, the sourcing of plant and animal material was difficult. Finding people who could observe and identify these curios and scientific specimens of knowledge was not easy. Secondly, there was the challenge of finding people to physically collect (or steal) specimens. Then, once specimens were obtained, they often went missing, were lost in sea wrecks, or died en route. Murphy focuses on the period of the eighteenth century, prior to the abolitionism of the late 1700s and early 1800s. She proposes that the connection between natural history collection and the widespread slave trade passed, unquestioned, amongst British naturalists.[2] This is precisely the kind of observation that characterizes Dark Botany, that is, a calling-out of the colonial British habit of turning-a-blind-eye. There is still resistance, today, to these kinds of acknowledgements that tell the truth about unethical activities by British colonizers.

During the eighteenth century, museums and herbaria became richly stuffed with scientific collections. Murphy’s book reminds us that this was usually at the expense of West African peoples, in the name of commerce. The routes of the British slave trades were determined by the will of such men as English apothecary and naturalist James Petiver. He worked hard to acquire collections of plants and insects in order to publish collection texts that could communicate the wealth and breadth of Britain’s knowledge of West Africa and the wider world. Petiver understood that the routes and successes of slaving ships were entangled with new natural history collections. This was a period where the imperial fervor to collect and exhibit was at its zenith. Monopolies of collecting, and maintaining them, were imperative. These were competitive industries—slavery and botany.

As Murphy explains, British naturalists’ exploitation of the commercial slave trade to collect specimens from West Africa included an active and direct exploitation of the labor and knowledge of enslaved people.[3] There was more on offer than merely collating an impressive collection of beetles, bespoke and valuable as that was. As an apothecary, Petiver also knew the potential of plant drugs, such as sassafras and snake root. Ship surgeons and slavers were keenly aware of the illnesses that plagued the British plantation owners and workers. The collecting of people, as Petiver knew, also held the potential for discovering new cures, for malaria for instance. Quinine was known as a potential cure, and its source—the cinchona plant—was lusted after as a highly prized cure and medicine.[4] The slave voyages also presented opportunities to find and develop perfumes, spices, and dyes, as well as other substances such as coffee and chocolate. An example of a valuable dye was cochineal, a red dye, which was more valuable than silver.[5] The commerce of inoculations for illnesses such as smallpox was rising. The bottom line of medicine was to prevent high mortality rates among slaves and slavers scattered across the Atlantic and Pacific island countries.

The Duke of Chandos (James Bruydges) was the Royal African Company’s most notable investor. Chandos was known to ask his friend Hans Sloane advice on how to bio-prospect in West Africa.[6] Sloane is well known as the physician who spent time in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean, from where he collected over 1000 plants, large supplies of cacao, and bark for quinine. He married a wealthy heiress from a slaver family who managed sugar plantations in Jamaica. He was elected to the British Royal Society in 1685.[7] These were the men orchestrating the slave ship routes and the associated plant activities. Without a doubt, profit and extractivism were at the core of their activities. Personal and national wealth was the driver.

The Royal African Company, a key area of the book’s interest, identified that profit relied not just on slavery but on collecting natural history specimens and knowledges attached to the medicinal value of those specimens. As Murphy expounds, all of these capitalist profiteering or bio-prospecting were at the expense of First Nations peoples who were already compelled to lose their families and livelihood. They also lost their cultural knowledge as well as their freedom. Perversely, such collectors as James Petiver and Hans Sloane also collected dolphins, shells and man-made curiosities. Another ship surgeon, John Burnett, collected sloths, caterpillars, wingless cockroaches, three toed sloths, terra macomachi—a cure for ringworm—and counter poisons from Jamaica. This too was the epoch of poison fear. Slavers were in constant terror of being poisoned by knowledgeable Indigenous peoples.

Murphy attends to all the malevolence and mastery involved in this epoch of bio-piracy and nationalistic natural history fervor with a calm narrative voice. She dedicates a whole chapter to the Royal African Company, which held a monopoly on all English trade with West Africa. The book includes a chapter on the colonial search for the rare goliath beetle of West Africa and a chapter allocated to the nineteenth century British slave trader residences in the Spanish Americas, which had valuable natural commodities and was in some ways kept a secret from other nations. Murphy’s text benefits from her arduous research of slaving company records, naturalists’ correspondence and diaries, and museum catalogues. This tireless research fits into the concept of Dark Botany and follows that process of telling the truthful stories about Indigenous erasure from botanical institutions and texts. Her work, which throws light on the darker connections of the times, results in a book teeming with historical information, while also maintaining her central argument that slavery and naturalism were inextricably dovetailed. Captivity’s Collection is the latest in a darkly botanical interrogation of the spread of botanical interest and inquiry. It lays bare the British imperial fervor that drove botanical and natural history exploration. Murphy is doing Dark Botany, and I thank her for it.

Prudence Gibson is an author and academic at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. She is Lead Investigator of an Australian Research Council grant in partnership with Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens Herbarium. Her recent books are The Plant Thieves (NewSouth Books 2023), The Plant Contract (Brill 2018), Janet Laurence: The Pharmacy of Plants (New South Books 2015) and The Rapture of Death (Boccalatte 2010).

Captivity’s Collections: Science, Natural History, and the British Transatlantic Slave Trade

By Kathleen S. Murphy

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press

Paperback / 256 pages / 2023

ISBN: 978-1-4696-7591-6

[1] Prudence Gibson, “Decolonising plants in the Sydney Herbarium,” in History, Prospects, and Applications of the Vegetal Turn: Plant Minds, Persons, Relations, and Rights, ed. Di Paola, Marcello (Springer, 2024).

[2] Kathleen S. Murphy, Captivity’s Collections: Science, Natural History and the British Transatlantic Slave-trade (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 5.

[3] Murphy, 28

[4] Murphy, 63

[5] Murphy, 82-83

[6] Murphy, 49-69

[7] Mary Farr, “From Hans Sloane to Bluegrass Music” Lecale Review (2022), 20.

Published on April 15, 2024.