This is part of our special feature, Europe and NATO Since Ukraine.

“Last time our capital experienced anything like this was in 1941 when it was attacked by Nazi Germany,” tweeted Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba. “Ukraine defeated that evil and will defeat this one.”

Around 8 a.m. Pete and I decided to go outside for some fresh air and threw on our helmets and vests, something I never could have imagined needing to do in Kyiv. We found a ghost town. There was no traffic. Cafes and shops were closed. The streets in Kyiv’s old town were almost completely empty. The air-raid sirens howled periodically, reverberating between the city’s historic brick buildings. Other than that, there was little sound. The haunting silence made the caws of crows seem especially loud. We walked past the Golden Gate, where I’d typically find people hustling to work and sipping espresso, and there was nobody. Turning north, we wandered towards St Sophia’s Cathedral to find the square in front of it also empty, save for the monument of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman, atop his steed with his bulava (ceremonial mace) in hand and his back toward Moscow. It felt like a scene from an apocalypse movie where the main characters wake up to find themselves the last people left on earth.

Soon, though, other people emerged. Journalists spilled out from hotels and residents from their apartments. Chaos and confusion ensued, as everyone tried to figure out what to do. Of Kyiv’s more than three million residents, around two million decided to flee. Those with cars stuffed whatever they could fit inside, while others huffed it with backpacks to the central railway station. Many foreign correspondents did the same after consulting with their security teams. My security team at BuzzFeed News left the choice to me and Pete and Isobel, my BuzzFeed News team. But if we wanted to stay in Ukraine, they asked that we at least move someplace outside of the city center, in case the Russians managed to get in or surround the city. Being someplace on the southern edge provided several possible escape routes that would take us west. So we packed into the rented white Ford SUV and set off, unsure exactly where to go but in touch with a group of other journalists who decided to do the same.

By mid-morning, in Kyiv and everywhere else across Ukraine, people were mobilizing. The army rushed to all corners of the country where Russian troops were advancing. Territorial Defense Forces composed of ordinary civilians who just days earlier were reporting to work at tech companies, schools, supermarkets, legal practices, and everything in between, gathered in predetermined meeting places to get armed and hear their orders. Ammunition depots swung open their doors at the request of Zelensky and handed a rifle to anyone with a passport willing to fight the Russians. Faction leaders in parliament sent a mass text to lawmakers to let them know that “weapons are being given out at the National Police headquarters on Volodymyrska Street.”

On the road, we found a massive traffic jam of people fleeing. There were mile-long queues at gas stations and lines of people outside pharmacies and supermarkets, as those planning to stick out the attack looked to stock up on food and essential supplies. Defensive lines were being built everywhere in between the major military ones set up around the inner and outer rings of Kyiv. Checkpoints were erected with cranes moving massive concrete blocks onto highways and major arteries leading to the capital’s center. Police and Territorial Defense volunteers dug trenches with excavators and shovels in yards and flowerbeds. Government buildings were barricaded with dump trucks and police vehicles while the windows were reinforced with sandbags. The bridges over the Dnipro river were closed. In the streets, people were making Molotov cocktails by the hundreds with empty booze and beer bottles. I saw several empty bottles of sparkling wine from the Artwinery factory in Bakhmut used to make the home-made firebombs. Among the materials were blocks of polystyrene foam that people broke into tiny bits and added to the explosive mixture so it would stick better to their targets and burn for longer.

We also came upon people tearing down and covering road signs with black paint. Taking a page from Britain in World War II, Ukravtodor, Ukraine’s government agency responsible for the national highway and road system, had put out a call on social media for “all road organizations, territorial communities [and] local governments to immediately begin dismantling nearby road signs.” It wanted Ukrainians to rip them down or else paint over them to confuse the invaders. Ukravtodor’s post included a mock-up of a highway sign that underscored the public’s attitude toward Russian troops. “Fuck off,” it read beside an arrow pointing ahead. “Fuck off again,” read the words beside an arrow pointing left. And next to a third arrow veering to the right was a demand to “Fuck off to Russia.”

“The occupier must understand that he is not welcome here and [we] will resist on every street, every road!” Ukravtodor added. “Let’s help them go straight to hell.”

That day and in the following days, we passed several colorful messages now scrawled across the traffic signs. One appealed to the enemy’s humanity: “Russian soldier, stop! How will you look into your children’s eyes? Leave!” Another, spray-painted over in red, served as a warning: “Welcome to hell, you Russian motherfuckers!” Billboards were also plastered over at record speeds with messages such as “Those who come at us with a sword will die by a sword.” That one was paired with the image of Kyiv’s Towering Motherland statue wielding her sword in one hand and Putin’s head in the other. Similar messages were also shown on electronic road signs above highways typically used to transmit information about water conditions and traffic accidents. Several of them broadcast the first battle cry of the new war: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself,” they said. It was an homage to the final communication made by Ukrainian border guards stationed on Snake Island, a small rock off the coast of Odesa, just before the Russian missile cruiser Moskva opened fire on them in the first hours of the invasion.

Our convoy collectively looked for AirBnB spots we could rent together or any hotel with available rooms. The only place we could find was a motel on the side of a main highway. It was on the southern part of the outer ring of the city and could give us a jumpstart if Russian troops stormed into the capital from the north. But we realized after we had already paid and checked in that it was only ten miles east of Vasylkiv, a main Russian target. The first clue was the mobile 9K35 Strela-10 air-defense system parked 100 yards north on the side of the highway. The second was the constant roar of fighter jets overhead. We were beneath their flight path. Luckily, they were Ukrainian and Pete snapped several shots of them with his telephoto lens, which allowed us to see that the country’s air force was still alive and working, and armed with various missiles on their wings. They zoomed fast and low in pairs about every 30 minutes for most of the evening, heading north to engage Russian aircraft, then turning back south to refuel and reload.

The hotel’s kitchen was closed but the hotel operator, a nervous man who was careful to write by hand all of our passport details before turning over the room keys, let us dine in the restaurant area and use plates and silverware from the kitchen. The only condition was that we keep the lights off. So our group of foreign correspondents dined on a meal of Lays potato chips, bread, cheese, smoked sausage, tomatoes, olives and Snickers bars, washing it all down with Staropramen tall boys, by candlelight.

Afterward, I tucked myself into a bed that was covered with a hand-stitched blue-and-white quilt that had little hearts on it. Inside the hearts were the words “Home sweet home,” in English. I called Bri, who was sick with worry back at our home in Brooklyn, to let her know I was safe.

Before I dozed off, I saw a new post on Zelensky’s social media accounts. It was a video. He had emerged from his bunker and with his top aides at his side walked out to Bankova Street to film what might be the shortest yet most important address he would ever make.

“Good evening, everyone,” he began. “Ya tut” – I’m here. “We are all here. Our soldiers are here. Civil society is here. We are defending our independence. We are defending our state. And this is how it will be from now on.” The president’s video was proof of life with a crystal-clear message: he was still at the helm, steering the ship. “Slava Ukraini,” he said as he signed off. The rest of the group responded: “Glory to heroes!”

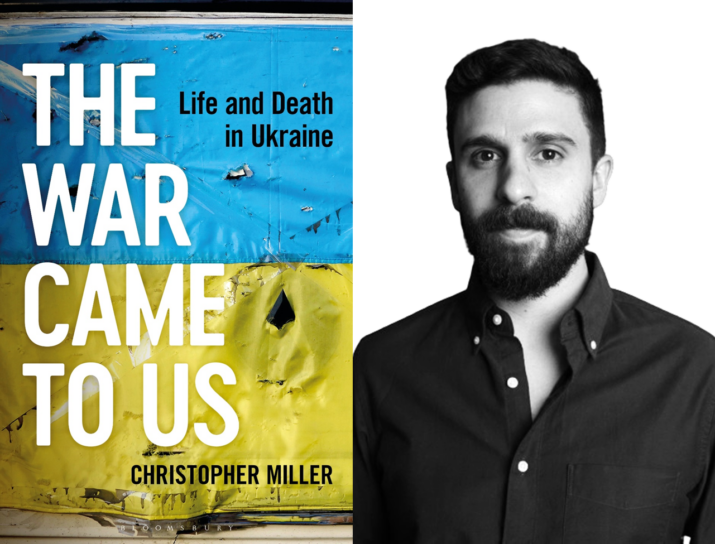

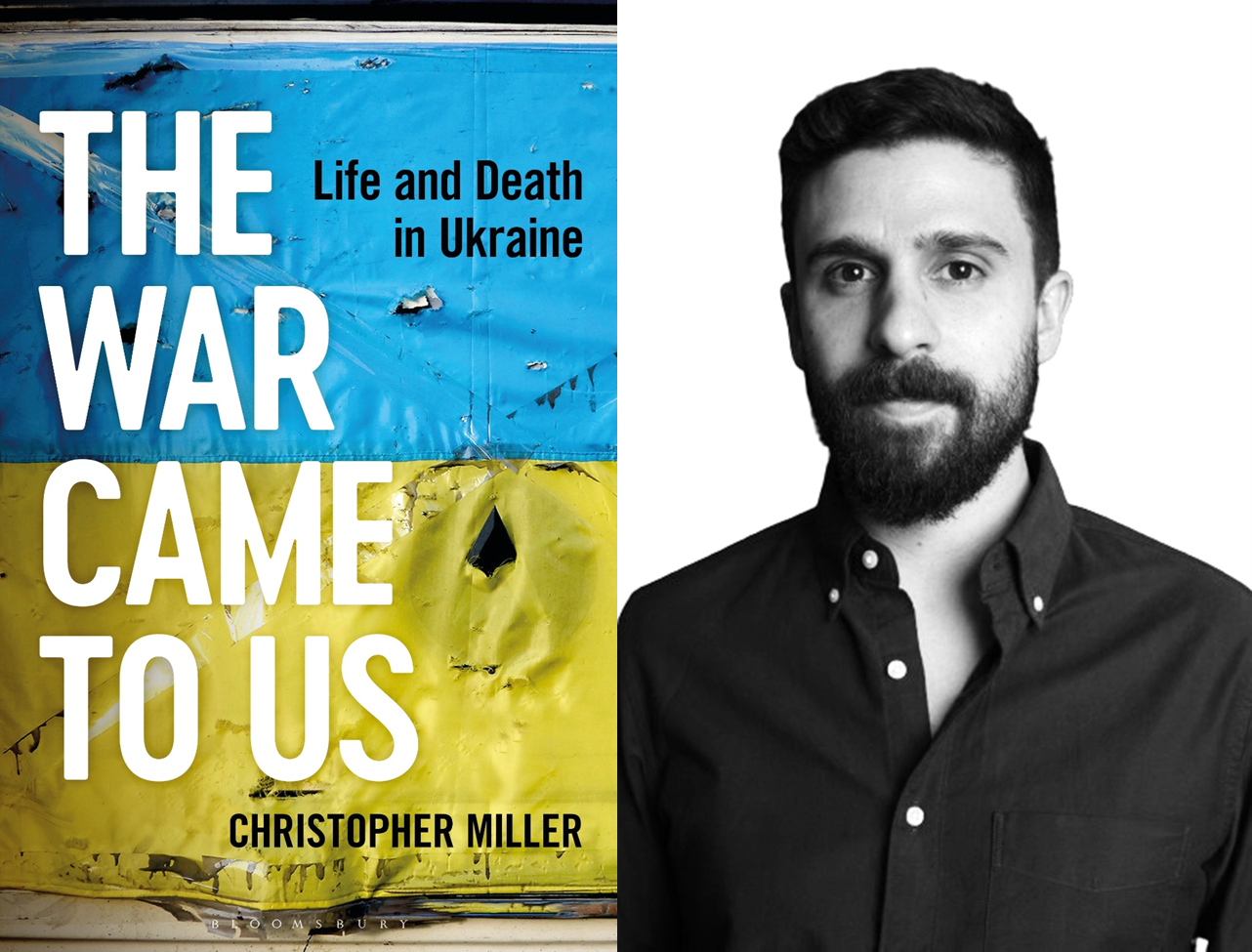

Christopher Miller is an American writer and journalist who has reported from Ukraine and across Eastern Europe for more than thirteen years. Since 2022, Miller has been the lead correspondent in Ukraine for the Financial Times, covering Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country. He was previously a world and national security reporter for POLITICO, senior world correspondent for BuzzFeed News, and correspondent for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Kyiv. Miller has reported from the front lines of Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and the Kremlin’s invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. He was part of the Kyiv Post team that received the 2014 Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism for on-the-ground coverage of the revolution. Miller’s journalism has also appeared in The Times, The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Telegraph, The Independent, Vice News, CNN, and many other publications. He appears frequently as a guest on major television news programs, including those on CNN and MSNBC, as well as podcasts and radio programs produced by The Financial Times, The BBC, RTE, Monocle, and more.

This excerpt from THE WAR CAME TO US: LIFE AND DEATH IN UKRAINE was published by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright @ Christopher Miller, 2023.

Published on February 15, 2024.