This is part of our special feature, Europe and NATO Since Ukraine.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Zenia Tompkins.

Did You Fall Off the Moon, or What?

“This train won’t stop in Svatove!” the female conductor announces, dumbfounding one passenger after another.

“But I’ve got a ticket!”

“Did you fall off the moon, or what? There’s war there!”

“But I was just there just two days ago!”

“And that was two days ago! We’re heading to Kharkiv now, and then on through to Lozova. Be grateful that the train’s at least running that far,” the conductor snarls. “Because we could strike. Why should we work where bullets are flying?”

A passenger named Auntie Liuba, a dumpy village woman of pre-retirement age, is traveling to the Troitske District in the northwest of Luhansk Oblast. Like me, she was supposed to get off in Svatove. She and I sit down next to each other and begin considering our options. Overhearing us, a freckle-faced university student named Yaroslav, who’s in a similar situation, joins us. We end up deciding to spend the night all together at the train station in Kharkiv.

“Because it’s very scary alone,” Auntie Liuba says, pressing her clasped hands to her chest. “With what’s going on these days.”

My heart twinges. It turns out, however, that she isn’t talking about the war, but about thieves. Auntie Liuba is a quarrelsome, thickset woman with short gray hair. She describes to me how the Ukrainian army drives around her village on armored personnel carriers, and all the village women go out to feed the “naked, barefoot, hungry boys.”

“It’s because of them that there are tanks in my village, and now because of them I can’t even make it home. Dogs. Bastards. And that’s not all!”

“What else?” My heart skips a beat again.

“There’s been no rain in over two weeks!”

Auntie Liuba, Yaroslav, and I are ready to spend the night on our bags, but at midnight, by some miracle, we find a ride. The husband of a young woman in our railcar who was also heading to Svatove has come to pick her up from Kharkiv.

“Speak Russian, to not attract unnecessary attention,” he advises me, before switching back to Ukrainian Surzhyk.

I inquire why it is that separatism hasn’t taken root in the northern Luhansk region where they live, in contrast to the south of the oblast. But I don’t hear any patriotically pro-Ukrainian pronouncements.

“Where we live, every separatist needs to first milk four cows before doing anything else,” Auntie Liuba grumbles.

Yaroslav laughs at her answer and adds, “And also, by the time you make it to where we live, your wheels will fall off. Even if you’re in a tank.”

Auntie Liuba spits poignantly to indicate her agreement.

During our drive to Svatove, which takes half the night, we pass three Ukrainian army checkpoints in our old boxy sedan. Out in the steppe, we almost run over three foxes that leap out in front of our headlights one after another, their greenish, luminescent eyes flashing. And our wheels really do almost fall off.

“Svatove’s a big city these days!” Auntie Liuba mutters bitterly as we approach the unilluminated town through purplish hills in the middle of the night. After the separatists captured Luhansk, the administration of the entire oblast flocked to this district center.

Auntie Liuba and Yaroslav drive on to Troitske further north. Meanwhile, I wait for daybreak at the Svatove bus station in the company of three drunk women, scared to go out into an unfamiliar city with what’s going on these days. The women sit around a radiator pouring alcohol into plastic cups. They aren’t snacking on anything. They offer me a drink too, but I decline. Instead, I take a nap, my back leaning against the radiator.

Finally, a dewy morning dawns, and I venture out into the “city.”

For a better understanding of the newly minted city’s flavor, it’s worth noting that there isn’t a single building taller than three stories in Svatove. Actually, no, that’s incorrect. There’s a four-story white concrete district administration building, which, in view of the circumstances, has temporarily become the oblast administration building. Old bicycles and scooters from China, which are sold on credit here, predominate in the town. The most common car is the boxy Soviet-era Zhiguli sedan, behind the wheel of which is typically a guy with a long Cossack-style mustache that extends almost from mid-cheek to mid-cheek.

So, here you are walking at seven o’clock in the morning through the center of a well-swept and quiet town, bathed in dew. You’re finding yourself moved by the welcoming calm and serenity of provincial Ukraine, when suddenly you realize that from under a kiosk, from ground level, the barrel of a machine gun is aimed at your chest.

The machine gunner shifts both his barrel and his gaze away, and lets you pass. He isn’t alone here. In the square in front of Svatove’s House of Culture, there are a few dozen of them. All of them are just the way you—having spent your entire life in a peaceful country—always imagined “armed to the teeth,” with under-barrel grenade launchers, bazookas, bulletproof vests, torsos strung with metal, grenades in plain sight, and about a dozen magazines per Kalashnikov rifle.

The town is tiny; everyone can see everyone and everything. To ensure that you, a visitor, aren’t misunderstood when you’re encountered again, you go to the local authorities to introduce yourself and to get the phone numbers of the higher-ups just in case. The windows of the first story of the police building are barricaded with sandbags all the way to the top. Dozens of people with machine guns keep you from walking up too close to it. The town hall is locked and unlit. On the roof of the white concrete government administration building, the black figures of machine-gunners loom along the entire perimeter. In front of the building, dozens of buff men in body armor over black T-shirts sit in black jeeps and SUVs.

“Our police force is unreliable,” they explain to you in the administration building. “But the Ukrainian army has gotten them back in line.”

Right now, the oblast police force is headed by that same general who, only a month earlier, was a “people’s policeman” in the self-proclaimed “people’s republic.” He’s now switched to the other side, having calculated that it would be more advantageous for him. Among the people, this police general is known as Tolik Zhelieziaka, or Ironman Tolik. The nickname is supposed to reflect his character, as well as the fact that he protects the semi-legal scrap metal market in the oblast.

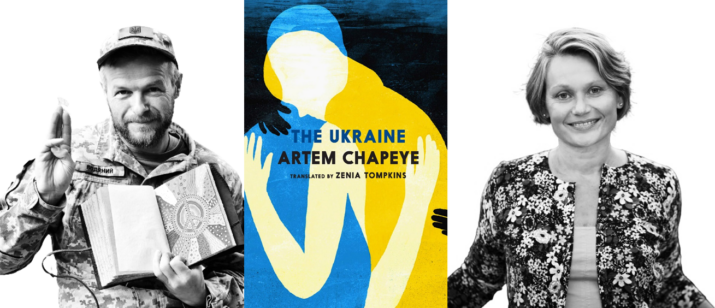

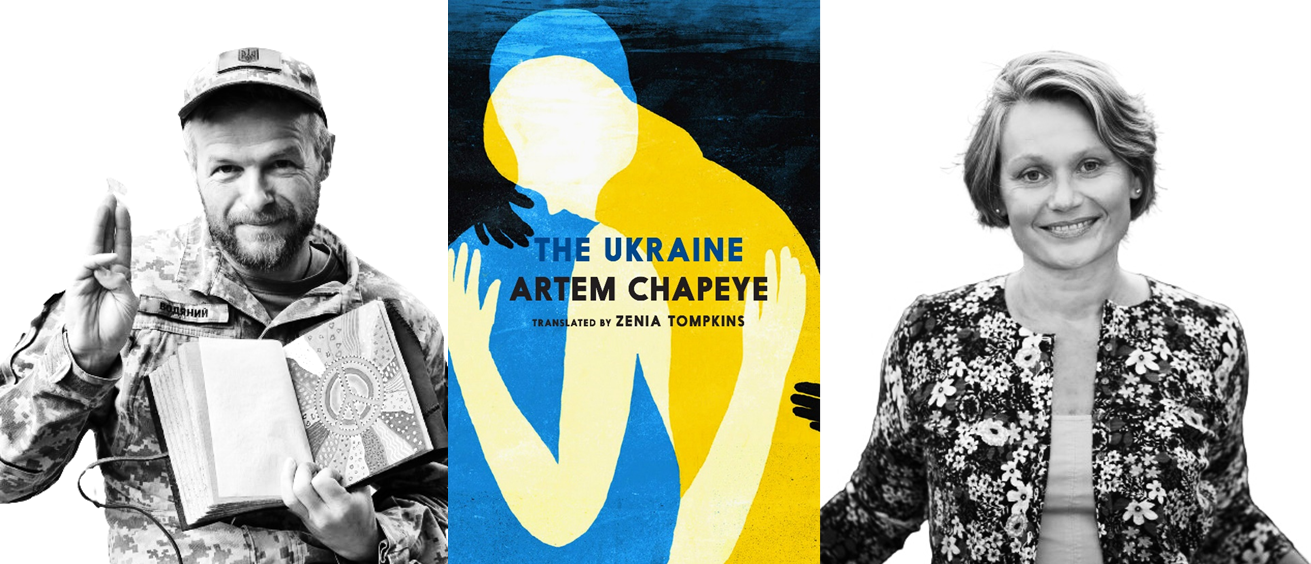

Artem Chapeye is an author of both creative nonfiction and popular fiction who was born and raised in the small Western Ukrainian city of Kolomyia and has spent much of the last twenty years living in Kyiv. He is the author of two novels and four books of creative nonfiction and is a co-author of a book of war reportage. A four-time finalist of the BBC Book of the Year Award, his recent collection The Ukraine was one of three finalists in the award’s new nonfiction category in 2018. Artem is an avid traveler who spent close to two years living, working, and traveling in the US and Central America—an experience that has greatly informed his writing. His work has been translated into seven languages and has appeared in English in the Best European Fiction anthology and in publications such as Refugees Worldwide, translated by Marian Schwartz. Artem is a past recipient of the Central European Initiative Fellowship for Writers in Residence (Slovenia) and the Paul Celan Fellowship for Translators (Austria), as well as a finalist of the Kurt Schork Award in International Journalism. He serves on the board of PEN Ukraine.

Zenia Tompkins is an American literary translator and founder of The Tompkins Agency for Ukrainian Literature in Translation (TAULT, tault.org). Her published books include adult fiction, adult nonfiction, and children’s. Zenia’s work as a translator and promoter of Ukrainian literature has been featured by The New York Times, The New Yorker, Poets & Writers, BBC Radio, National Public Radio, and Public Radio International. She will be devoting 2023 and 2024 to working exclusively with Ukrainian authors who have enlisted in Ukraine’s armed forces since the Russian invasion. Since its inception in 2019, TAULT has worked with over one hundred of Ukraine’s top and emerging authors.

This excerpt from THE UKRAINE was published by permission of Seven Stories Press and Seven Stories Press UK. Copyright © Artem Chapeye, 2024. English translation copyright © Zenia Tompkins, 2024.

Photo Artem Chapeye by courtesy of author | Photo Zenia Tompkins by Kate Mitchem

Published on February 15, 2024.