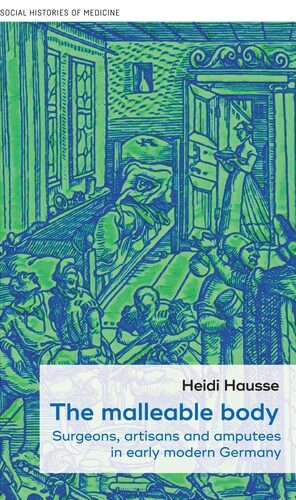

The Malleable Body: Surgeons, Artisans, and Amputees in Early Modern Germany by Heidi Hausse

The saying “that costs an arm and a leg” may be an economic truism today, but in early modern Germany it was often a physical and traumatic reality. The early modern period saw the outbreak of vast military conflicts such as the Thirty Years War, introducing Europe to an increased scale of warfare and the expanded use of perilous military technologies such as gunpowder. War, however, was not the only way to lose a limb. Europeans at that time could also face amputation after exposure to the elements, disease, botched medical procedures, and dangerous accidents that occurred in everyday life. These common accidents provided surgeons with more experience to learn, revise, and create new approaches towards amputation. Surgeons previously hesitant to manipulate the body’s shape were, just two centuries later, experimenting and creating new techniques to do just that. How and why did amputation transform by 1700? And what can bodily trauma tell us about the larger collision of knowledge-making, medicine, technology, and disability in early modern Germany? Heidi Hausse’s book, The Malleable Body: Surgeons, Artisans, and Amputees in Early Modern Germany examines the history of amputation and prostheses to answer these questions and shows how surgical interventions, medical knowledge, ideas of the body, communal decision-making, and experience all gave rise to a malleable body.

Hausse asserts that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, surgeons, amputees, and artisans used experimentation, discussions, and commissions to create and perpetuate the possibility of altering and enhancing the human body. Her combination of two source themes makes her effort to fully understand this malleable body possible. First, Hausse uses surgical treatises to provide a historical analysis of learned and vernacular amputation techniques, and how they changed over time. Second, her close analysis of surviving artificial limbs sheds light on the practical and material side of amputation. Hausse’s innovative and comprehensive work melds the history of medicine, material culture, technology, and disability together to provide a complex non-linear story in which surgeons, artisans, and amputees collaboratively developed new prosthetic technology. In doing so, they participated in various forms of both written and embodied knowledge-making.

The author explores each of these actors in her book as she guides the reader through different types of knowledge-making to bring the story of early modern amputation to life. She begins by laying out connections between surgeons and their craft, including how to diagnose a dying limb and the importance of social deliberations when it comes to amputation. The work then confronts various seventeenth century instructions on “proper” methods of amputation and the heated debates that followed about the body, technology, and competing approaches, such as the use of flap amputation or the preservation of extra healthy flesh during a procedure. Finally, Hausse confronts how surgeons approached issues of phantom limb pain and artificial replacement. In sharing these stories and intimate scenes, she spares no details while remaining respectful to her historical subjects. In one instance, for example, she writes about Fabry von Hilden who accounts a troubling case where he lost a patient, Stephan Toppinus, to der kalte Brand or “the cold fire” before amputation could occur. Through these accounts, Hausse deftly guides the reader through an exploration of the complex dialogues of medical timing, social dimensions of amputation, and new methodologies, all while uncovering the voices of vernacular surgeons. Teasing out these various treatises and stories of amputation and prosthetics over two centuries, her work deepens the reader’s understanding of knowledge-making, how this knowledge spread, and its application in medicinal practice.

The social dimensions investigated by Hausse help depict the true complexity of amputation in the early modern Germany. The idea of pursuing amputation to save one’s life may seem like a logical move. The reality of cutting off a limb in the early modern period, however, was a grave decision, and doctors and patients often sought the encouragement and consent of one’s surrounding family, friends, and pastors before undertaking the procedure. Indeed, according to Hausse, the patient’s family members were often a surgeon’s greatest advocates in convincing patients to undergo the surgery, especially after the surgeons had convinced them amputation was necessary. After the patient’s social circle agreed the limb should be removed, medical regulations dictated that surgeons had to consult with other practitioners. Hausse shows that these peer-consultations were regulated differently depending on the local environment and were far stricter, for instance, in urban areas like Munich, Augsburg, and Cologne. Time proved to be a surgeon’s worst enemy as they had to first convince patients and families of amputation, then seek outside advice without delaying the procedure too long. Nonetheless, each social dimension Hausse confronts in the book shows that in early modern Germany, these medical decisions were often communal ones, built of various steps towards group consensus.

Over the course of the work, Hausse uniquely segues from a thematic focus on practical experience, social dimensions, and textual knowledge of the putrefying body to analyzing amputation artifacts. For this analysis, Hausse uses methodologies grounded in material culture studies to demonstrate how these artifacts, specifically mechanical arms and hands, showcased the myriad ways patrons and artisans played an active role in reshaping bodies. Unlike other prostheses common at the time—such as silver noses or wooden leg shafts—upper-limb prosthetics had both practical and aesthetic functions, for example through the development of moveable finger joints or flesh-toned paint. Previous scholarship has analyzed prosthetics through the lens of warfare and military technology. Hausse, however, pushes the interpretation of these artifacts further by contextualizing how each object worked and what they reveal about the individuals who made and commissioned them. The Ruppin Balbronn Hand, for instance, not only shows us its patrons’ desire to reshape their body but also suggests how prosthetics became a creative extension of the wearers to suit their needs, appearances, social perceptions, and budgets. Hausse asserts that the mechanical limbs were not just symbols of a lost body part. Rather, behind the iron, wood, leather, or paint, a deeper dialogue resided, one in which elite amputees with the means to commission custom limbs directed artisans to design devices that followed cultural trends and combatted negative stereotypes. Here, Hausse makes her most notable intervention. While the surgeon first changed the body with amputation, the elite amputee-patron and artisan also represented historical actors revising the body again with mechanical hands that embodied cultural prestige, self-sufficiency, and longevity. The action of these patrons and their material practices, in turn, influenced the malleable body, its possibilities, and medical perceptions of prosthetics and disability.

Altogether, Hausse’s detailed archival work creates an intellectual, communal, and sophisticated history of amputation, while also challenging future scholars to embrace a new vision for the field of premodern medicine and the body. In this vision, scholars should use varied methodologies and areas of study to elaborate on their research, much like the surgeons in her work. By creatively threading together various written and physical sources, Hausse reminds us of the scholarly benefits that come through by embracing the intertwined histories and methodologies of material culture, disability, technology, and medical studies. Furthermore, Hausse’s ambitious book leads the charge in depicting an intricate community that existed within premodern medicine, one where various surgeons, amputees, and artisans came together to create the idea of a manipulated body. Overall, The Malleable Body is a must read for graduate students and scholars seeking to understand the complex nature of medicinal knowledge-making and its impact on early amputation as a medical, cultural, and social issue. It also serves as an important bridge for scholars of disability, technology, and medicine who desire to deepen their understanding of surgical literature, perceptions of the body, and the capacity of premodern medicine in the early modern period.

Alyssa Culp is a visiting assistant professor at Illinois Wesleyan University. She holds a PhD in history from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Her research focuses on the intersections of science, medicine, and local culture in nineteenth-century Germany.

The Malleable Body: Surgeons, Artisans, and Amputees in Early Modern Germany

By Heidi Hausse

Publisher: Manchester University Press

Hardcover / 288 pages / 2023

ISBN: 9781526160652

Published on February 15, 2024.