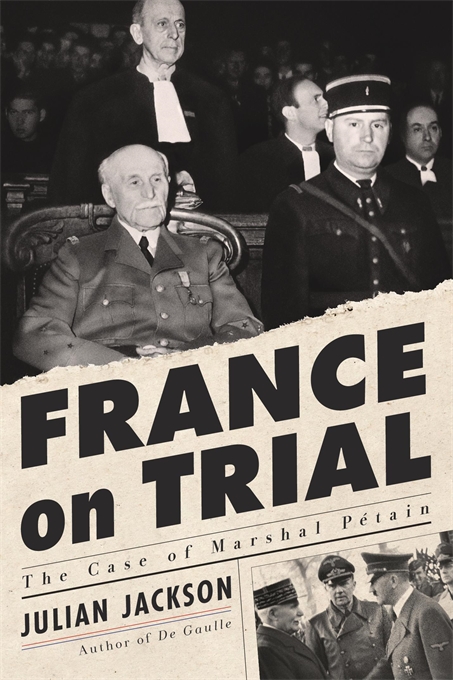

Amid the sound and fury of events, how and on what basis—not only ethical, but more problematically legal—can we justly attribute individual and collective responsibility for historical crimes? Instead of proceeding from theoretical postulates, Julian Jackson’s masterful work enables the reader to apprehend the case of Marshal Pétain in the unsettlingly complexity of the German defeat and occupation of France as well as of the murky realities of the human—all too human—protagonists of his trial. Pétain, known as le Vainqueur de Verdun, had been brought into Paul Reynaud’s ministerial team in May 1940, to bolster morale, and, once he had replaced Reynaud as prime minister, arranged for an armistice with Nazi Germany in June 1940. In the summer of 1945, Pétain faced judgement for having led his government, headquartered in the town of Vichy, in the politics of collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Epistemological fallacies notwithstanding, Leopold von Ranke’s imperative of understanding the past “as it actually was,” offers a tempting description of Jackson’s narrative approach. He carefully lays out France’s situation on both the national and international scenes in the final phase of the Second World War and situates the major political, military, and ideological figures of the period. Jackson retraces Pétain’s itinerary from his humble peasant origins to his initially modest then celebrated military career and on to his seeming apotheosis as a father-savior figure for a France devastatingly humiliated by the May-June 1940 onslaught by the Wehrmacht. Jackson then narrates the legal proceedings of the Pétain trial in painstaking—and painful—detail: painful because the human turpitude of lies, betrayals, and base, often cowardly, self-interest are everywhere visible in these last few months of the German occupation of France. We find ourselves having to consider issues of politics, justice, ethics, history, and memory in their multifaceted, unwieldy dimensions. The matter of assembling and assessing the endless array of available documents to use as evidence offers a case in point, since these documents did not lend themselves to smug pronouncements or ready judgements at the particular time of their emergence. Jackson harbors absolutely no indulgence for the politics of collaboration and brutal suppression of the Resistance of Pétain’s government—“Vichy” for short—nor for its considerable role in identifying, arresting, detaining, and deporting to Auschwitz more than 75,000 Jews. The crucial legal questions of individual intent and responsibility as applicable under the existing legal statutes proved difficult to parse out in the summer of 1945, however.

Jackson lays out the personality, itinerary, and political orientation of each witness called during Pétain’s trial, exposing the flaws of a legal case that placed the blame for a host of France’s faults and shortcomings so squarely on Pétain’s individual shoulders: Vichy had in reality resulted from an entire array of collective, institutional, and widely distributed failures. Pétain had indeed often played a pivotal role but an inconstant and inconsistent one: as François Mauriac pointed out, many within and without that stifling courtroom, beginning with most of the now largely discredited Third Republic notables testifying against Pétain, could have usefully reflected on their own responsibilities. Jackson exposes the tawdry deficiencies of the judicial apparatus as configured at the time and characterized by a largely incompetent presiding judge ethically compromised for having himself sworn an oath of loyalty to Pétain. Jackson also introduces readers to an intemperate lead prosecuting attorney, who was similarly compromised for having participated in Vichy’s denaturalization commission. The jurors are shown to have been politically biased, and key witnesses for the prosecution included prominent politicians such as Paul Reynaud. The latter, who had brought Pétain into his government and then resigned knowing that the Marshal would take over, bore no little responsibility for Pétain’s accession to power. Finally, Jackson exposes the dubious legal standing of the court itself. There was nevertheless a quite understandable, legitimate “thirst to understand exactly what had happened in 1940 when France had been defeated and French democracy had been swept away” (124). Indeed, “The first week of the trial was a kind of history lesson,” since, as one newspaper wrote, “the disastrous events of the year ’40 are still not fully known except by a small number of initiates” (125).

If the trial itself did not effectively dispense that history lesson at the time, Jackson’s narrative does today, weaving testimonies with assessments of events and their actors. We see the tawdry, muddle-minded, incompetent, and often cowardly behavior of many of the leading figures of the doomed Third Republic, who self-righteously testified against the Marshal: Paul Reynaud, Édouard Daladier, Louis Marin, and Édouard Herriot, with the clear exception of Léon Blum, whose lucidity and honor had remained unscathed by the tumultuous weeks during which France fell and became occupied. The courtroom scene constituted a re-enactment of the poses, lies, manipulations, shortcomings, and confusion involved in the collapse of France’s political institutions in the wake of the bitter, crushing military debacle. The trauma, humiliation, and chaos of the fall of France were once again apparent in the words and actions of its leaders and elected representatives in the National Assembly.

Hence, the pertinence of Jackson’s title: not only Pétain but France itself was indeed on trial, beginning with the institutions and politicians of the Third Republic: “if Pétain was guilty so were the French – and so was France,” argued defense attorney Fernand Payen (259). Similarly, Jacques Isorni, also an attorney for the defense, hinged his defensive strategy on the conviction that the image of Pétain as a national father figure still held a grip on people’s minds, so that finding him guilty would mean convicting the French themselves as a nation and as individuals. If the Marshal were condemned, insisted Isorni, the very countenance of the French nation, with its various constituencies, would haunt the jurors and the entire nation forever. Of course, that rationale conveniently obfuscated the reality that, despite dominant tendencies in the public opinion at certain junctures, there had in fact been no uniform standard of thought and action either during the fall of France or under the Occupation. Again, assigning guilt or innocence either collectively or to any one man, be it Pétain or any of those who took the witness stand, was no simple matter. Pierre Laval—Pétain’s Minister of State—ambiguously and self-interestedly insisted that Pétain was always fully informed of every action taken by his premier, which illustrated the court’s conundrum:

Again and again, the trial came up against the problem of establishing the extent of Pétain’s personal implication in the actions of the Vichy regime. Had he taken political initiatives of his own? How much did he know? Had others acted behind his back? How much of a free agent had he been? What did he really believe? (213)

In moments of crisis such as the Allied invasion of North Africa, observes Jackson, the Marshal had been too tired and confused to either follow the rapidly unfolding situation or adopt a firm stance.

Particularly vexing was the question of criminal intent. How indeed to separate opportunistic posing from misguided patriotism, duplicity from delusion, preparations from plots to take power, or treason from incompetence? The fact remains that Vichy had committed serious crimes under the cover of Pétain’s prestige. Vichy had persecuted and registered Jews, interning thousands of them in squalid camps before assisting the Germans in deporting them to Auschwitz in cruelly inhumane conditions. Vichy had also tracked down, arrested, tortured, and executed resistors, often handing them over to the Germans. Pétain’s government had also forced hundreds of thousands of men and women to go work for the Nazi war machine in Germany and made French airbases available to German warplanes in Syria. Moreover, Vichy had recruited volunteers to go fight alongside the Wehrmacht on the Eastern front and given permission to the Germans to set up their defenses in Tunisia after the Allies had taken control of Algeria and Morocco. Defining those actions as crimes according to the existing legal code and jurisprudence and then attributing responsibility to specific individuals, however, proved problematical.

Despite Pétain’s ultimate conviction on the most serious charges of intentional treason, the trial did not deliver a legible pedagogy on what had actually happened to France over the course of previous years, i.e., from the time of the infamous Munich accords, which marked France and Britain’s ultimate act of appeasement, to the liberation of France and the return of Pétain. Nor did the trial provide any useful catharsis for the conscience of the nation, whose official collaboration with Nazi Germany had stained its international prestige while bringing it to the brink of civil war. Pétain’s legal guilt was only decided by the slimmest of margins, 14 to 13. These shortcomings were not lost on those who had observed the trial. On the verge of receiving the verdict, Joseph Kessel, who had been a resistance fighter, spoke of “An interminable silence, a silence which hardens, a silence which becomes like a presence. The presence of History” (272).

Jackson concludes his book by retracing France’s memory of the Occupation from the late 1970s to the present. Though he does not seem to think so, the Pétain trial and the legacy of the Marshal were not central but only peripheral issues of memory during these years. What was rather in question was the matter of French collaboration with Nazi Germany, and the focus was intensely placed on France’s active participation in identifying, arresting, detaining, and deporting Jews in France. In the last chapters of the volume, Jackson seems to assume that the memory of the Vichy regime and its crimes should align perfectly with that of Pétain. There is in fact not only a temporal discontinuity but, more importantly, a fundamental, historical, and ethical discontinuity between, on the one hand, the issues faced by an entire generation judging individual responsibility for state crimes committed over the course of events it had itself lived through, and, on the other hand, the questions raised decades later by generations with no direct experience of those dramatic events and much more keenly attuned to the political priorities of their own times. The former issues concern the judgement of a leader whose figure, voice, and policies were part of what unfolded, while the latter questions concern the various ways in which that leader’s image, discourse, and actions have been remembered or forgotten, represented or misrepresented, interpreted or misinterpreted, or exploited. As interesting as it is—particularly as conducted with such clarity and rigor as does Jackson—the exercise in a counterfactual history that aims to determine whether refusing the armistice while seeking governmental and military refuge in North Africa was a useful strategy seems rather pointless. Jackson’s summary of the fall of France makes it clear that Paul Reynaud, along with his government ministers—in particular General Weygand, his Defense Minister—not to mention the National Assembly, which decided to grant full constitutional and legislative power to Pétain, bore considerable responsibility for France’s military and political debacle. It only follows that Reynaud and Pétain shared a significant degree of responsibility for Vichy France’s ensuing subservience to Nazi Germany. Pétain and Vichy lost no time in singling out and persecuting the Jews and arresting political enemies, using both groups as scapegoats. Pétain’s government’s crucial role in the brutal repression of resistors and in the massive round-up, detention, and inhumane transportation of Jewish men, women, children, and elderly has been heavily documented for decades. We need not engage in convoluted counterfactual reasoning to know that Vichy’s actions and discourse were indeed criminal. The uncomfortable reality is that, instead of being something foisted onto France by an anomalous, totally marginal group of conspirators, Vichy was the unseemly excrescence of the sociopolitical pathologies of the Third Republic. These pathologies stemmed from the shocking German rout of France’s military forces, which had left the entire nation in confusion and disarray, starting with its elected leaders.

The trial of Pétain brought out deep-seated misfunctions, divisions, insufficiencies, and fatal flaws in the words and actions of the Third Republic’s elected leaders and society perhaps more than in its bureaucratic and military machinery. Cardinal Gerlier’s sadly famous declaration that “Pétain, c’est la France, et la France c’est Pétain” unfortunately did indeed largely characterize the French nation in its November 1940 iteration. Today, with its splintered political parties, exacerbated identity politics, and gilets jaunes, French political scientist Jérôme Fourquet’s archipel français suffers from increasing racism, xenophobia, and antisemitism, and perhaps even from a certain nationalist nostalgia. None of this trend stems from the tiny minority of diehard pétainistes and their antiquated cult of le Maréchal, however. While Pétain remained a highly charged figure for the generations that directly experienced France’s tragic involvement in the two world wars, for those born during and after les Trente Glorieuses, he has at the most only served as an ideological accessory. However, he has gotten little traction, as Jackson illustrates by assessing far-right presidential candidate Éric Zemmour’s curious and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to defend Pétain and Vichy in the context of France’s 2022 presidential election. Pétain has for the most part been historicized and no longer constitutes a significant issue in France’s public memory.

Nathan Bracher focuses on the narration of history and memory as Professor of French in the Department of Global Languages and Cultures at Texas A & M University. His monograph After the Fall: War and Occupation in Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française was published in 2010. Recent articles include “Biographie et histoire,” Europe No. 1125-1126, Jan. – Feb. 2023, and “Les historiens et leurs ombres: le passé à la première personne du présent,” French Politics, Culture & Society, Vol. 40, No. 2, Summer 2022.

References

Marrus, Michael R. and Robert O.Paxton. 1981. Vichy France and the Jews. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain

By Julian Jackson

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Hardcover / 445 pages / 2023

ISBN: 9780674248892

Published on February 15, 2024.