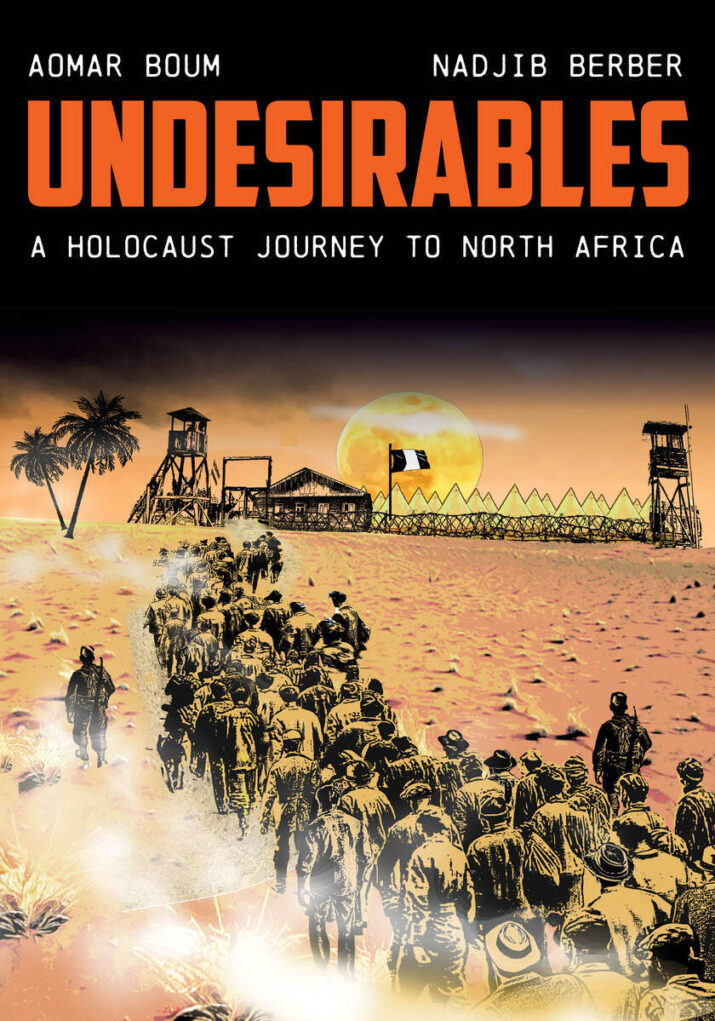

Aomar Boum and Nadjib Berber’s Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa is a recent addition to the ever-growing genre of comics on Jewish experiences during the Shoah. As the category of graphic narrative continues to grow, this volume further demonstrates that there are still new stories to be told by shedding light on some aspects of this historical period that have been ignored by comic art thus far. Turning to previous works by Boum clarifies this impulse. For example, in the introduction to the collected volume The Holocaust and North Africa (2019) Boum and co-editor Sarah Abrevaya Stein pointed to geographical oversights in Holocaust scholarship:

“Yet it is a striking quality of the diverse field of Holocaust studies that, even as our information becomes ever more detailed—accommodating even the most fine-grained digital mappings of Nazi concentration camps 13 —entire geographic realms of Holocaust history remain opaque.”[1]

The aim of The Holocaust and North Africa was to shed light on North Africa, which had remained a “murky zone” until then. Indeed, that volume provided invaluable material for understanding an understudied geography of the Shoah. In his most recent book, under review here, Boum turns to the graphic novel genre to fill further gaps in the official record. This time, however, he and illustrator Berber seek to bring the humanity of this region’s experience to the fore. In Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa, Boum and Berber relate the stories of individual lived experience Boum collected in his archival research. Both Undesirables and the earlier The Holocaust and North Africa thus reveal the “direct and indirect impact of Nazi persecution and mass murder in Europe on the Jews of North Africa;”[2] however, Undesirables pivots from standard forms of historical narrative to graphic historical fiction that uses the multimodality of the comics form to bridge the facts of The Holocaust and North Africa and the humanity of its semi-fictionalized composite characters.

Undesirables follows the story of Hans Frank, a fictional character created based on various Holocaust survivors’ testimonies discovered by Boum in archives across France, Israel, Morocco, and the United States. The composite nature of this character is immediately apparent in his biography, which opens the graphic novel: Hans is a German Jew born in 1904 to a Spanish Sephardic mother and an Ashkenazi German Jewish father. Since his mother was a leftist political activist and his father was apolitical and religiously observant, the protagonist represents multiple perspectives and identities present in Jewish communities across Europe. This diversity in Jewish life pervades the comic novel, and the reader is confronted with it in the pre-WWII context in Germany, France, and North Africa. In this context, the graphic novel presents observant and secular Jews sharing spaces and conversations on the politics of the period, on their relationships with Muslim neighbors and allies, and on the importance of Jewish activism during the rise of National Socialism. Following Éva Kovács’s approach in “The mémoire croisée of the Shoah,” Undesirables thereby succeeds at showcasing the flourishing communities that constituted the “substance of European Jewishness,” underscoring the cultural, as well as human, losses of the Shoah.[3]

The academic nature of this collaboration is apparent to any reader. Yet, unlike some comics on Holocaust experience that prioritize educating on the events of the Shoah, the narrative here is not stilted by the rigorously researched historical information. Rather, it balances the historical particularities with a lively, if serious, story that enhances and animates the reading experience in a way that other books outside of the graphic novel genre rarely do. The story traces Hans’s journey from Germany to North Africa, at which point it focuses on his struggle to survive alongside other “undesirables” in the brutal conditions of the forced labor camps of Algeria and Morocco. Through Hans’s journey, the reader witnesses the politics of Jewish persecution as it travels south, connecting the pervasive persecution of Jews from Central Europe to North Africa.

The “undesirables” featured in the graphic novel’s title, however, do not only represent the Jewish victims of the Holocaust; they also include political dissidents and Spanish Republicans likewise pulled into the Axis system of forced labor. While these camps were not designed for systematic mass murder, they nevertheless imported an ideology of persecution from Europe, which was applied directly by French and Italian authorities. Throughout World War II, Vichy authorities opened a network of seventy-three labor, disciplinary, and internment camps in North and West Africa, which by late 1941 housed close to 10,000 internees. Here, the authors’ attempt to “un-silence North and West African narratives of World War II” (100) appropriately positions Arab, Muslim, and Spanish Republican voices alongside the persecuted experiences of German, Moroccan, Algerian, and French Jews.

In addressing these multiple victim groups together, Boum and Berber make another important intervention in Holocaust literature. In part, this intervention relies on their disruption of the assumption that intercommunal conflict is both unavoidable and endogenously derived. Relations between Jews in North Africa and their predominantly Muslim neighbors were actually relatively quiet during this tumultuous period of history, with Muslim hostility toward Jews often incited by French officials in order to divert attention from Arab nationalism and growing pressure for independence.[4] Undesirables reflects these tensions. Once captured, Hans meets an Algerian nationalist and member of the political movement Étoile Nord-Africaine, Mohand, who is from Mza. Over the first few weeks of his internment in the DJelfa labor camp, which sat approximately 300 km south of Algiers, the friendship between the two men grows. Their weekly trips to the local village afford Hans the opportunity to meet the local rabbi, Rabbi Alloush, a “good friend” of Mohand (65). Over the course of multiple visits, Hans, Mohand, and the Rabbi discuss the peaceful coexistence of Jews and Muslims in the region. Hans continues to visit the Rabbi, and alongside Hans, the reader also continues to learn about the “thriving communities of Jews that have co-existed with Muslims” (67-68).

Importantly, Undesirables offers a corrective to our understanding of prewar and wartime Jewish-Muslim relations that is grounded in the format selected for the project: Boum and Berber turn specifically to the comics form to examine “how Muslims and Jews ‘see’ each other” (100). The literal picturing of these relationships and visual acknowledgement of the shared humanity of Jews and Muslims complement the historical facts contained within the pages. The volume not only illustrates peaceful coexistence in the past but helps the reader imagine a peaceful coexistence in the present and future.

Typically, I turn to comics on complex histories to help me understand the subjective experience of those dark and exceedingly difficult-to-access time periods. For example, Charlotte Schallié’s recent edited volume But I Live (2022) does an excellent job of capturing the emotional experience of survivorship through its graphic narratives that were co-created by Holocaust survivors and graphic novelists. However, Hans’s status as a composite character and the grounding of the fictional narrativization of this historic period in archival research reveal that the goals of Boum and Berber’s project are different from those of other comics. The documentary material interspersed throughout the narrative and the exposition riddled with historical facts reads as an archive come to life. Berber, the artist, clearly draws upon photographic evidence to render signage, posters, attire, and cityscapes as historically accurate as possible. However, despite the documentary value of this approach, his reliance on the perceived objectivity of facts results in a dearth of encounters with the subjective, emotional, and traumatic experience of the protagonists. Although the characters are fictionalized, the reader wants to empathize with them, as they are presented as part of a deeply painful and difficult historical period. Yet, that human connection remains elusive.

As a result of prioritizing historical fact over emotional reality, the authors missed many opportunities to connect with the reader. Hans’s experiences should have produced powerful emotional responses from him, and by proxy, the graphic novel’s readers. For example, Hans experiences extreme trauma when he witnesses the death of his fellow Djenien-Bou-Rezg inmate Michel, who has been immobilized and locked in a “tombeau,” essentially an open grave, for hours without food or water and directly exposed to the Moroccan sun. Still, instead of imparting the authenticity of this situation through an emotional confrontation with the pain and trauma of these characters’ experiences, Boum and Berber encourage their reader to connect with Hans through gestures towards historical “facts” behind the graphic narrative, such as documents providing evidence of truth-telling and other markers of authenticity that are typical in graphic historiography.

Despite this shortcoming, Undesirables offers opportunities to both reimagine Holocaust experience and appeal to different audiences through the multimodality of the comics form. The volume is an essential tool for prompting conversation on the impact of the Nazi Regime outside of Europe as much as on the role of comics and graphic novels in the historiography of World War II. For example, reading Undesirables alongside The Holocaust and North Africa affords learners the opportunities to consider what traditional forms of history are lacking in human rights discourses on atrocities while also considering the shortcomings that the fictionalization of the past entails, especially through graphic forms. In combination, Boum’s contributions to discourses of North African Holocaust experiences are an invaluable addition to both comics and scholarship covering this dark period of history.

Elizabeth “Biz” Nijdam is an Assistant Professor and settler scholar in the Department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, where she works, learns, and lives on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. She is currently completing her book manuscript Graphic Historiography: History & Memory through Comics and Graphic Novels (Ohio State University Press, 2024). Her research and teaching include the representation of history in comics, comics and new media on forced migration, intersections between Indigenous studies and German, European, and migration studies, digital and analog game studies, and feminist methodologies in the graphic arts. Nijdam is former secretary of the Comic Studies Society (2020-2023), sits on the Executive Committee of the International Comic Arts Forum (2014-), and is the Director of the Comic Studies Cluster in UBC’s Public Humanities Hub.

The reviewer thanks Barbara Freedman for her generous contribution to this review through consultation and conversation on this graphic novel.

Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa

By Aomar Boum and Nadjib Berber

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Paperback / 112 pages / 2023

ISBN: 9781503632912

[1] Aomar Boum and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, “Introduction“ in Aomar Boum and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, eds. The Holocaust and North Africa (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press: 2018), 8.

[2] Francis R. Nicosia, Nazi Germany and the Arab World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 449.

[3] Éva Kovács, “The mémoire croisée of the Shoah,” Eurozine, May 22, 2006: https://www.eurozine.com/the-memoire-croisee-of-the-shoah/.

[4] Nicosia, Nazi Germany and the Arab World, 450.

Published on November 21, 2023.