Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

By Hans Kundnani

Publisher: Hurst Publishers

Recommended by Jennifer Ostojski

What if the European Union’s foundational narrative was not just about peace, democracy, and the rule of law? In Eurowhiteness, Hans Kundnani argues that the European Union integration project at its core is an inherently white and imperial project. The book challenges domineering mythologies about the European Union’s beginnings, countering strongly against existing origin stories found in most textbooks and scholarly works these days and bringing race into the conversation. Any book about European identity will face an uphill battle, given the complexity and confusion surrounding the ideas of who belongs, who does not, and why. Kundnani finds a way to provide not only a succinct overview of the existing literature on nationalism, but he also describes quite well the on-going debates in the European identity scholarship. He takes the necessary leap from there and dives right into the emerging scholarship on post-colonial theories and decolonizing approaches, giving ample credit to those who have paved the way for him.

Kundnani outlines the utility of memory in the making of a European identity, showing its ability to demarcate the in and out groups and through that establish hierarchies of people. This memory engineering somehow “lost” the European’s colonizing past, and what emerged is instead a European mission to “civilize” the rest of the world, perpetuating a sense of identity-based superiority. “Colonial amnesia” has guided the European Union’s enlargement and integration project of the past few decades, encountering more obstacles in the past few years, which has seen more vested interest from the European citizens and their neighbors in questions about belonging to the supranational institution. Kundnani’s case study on Brexit shows most powerfully how the Union’s “colonial amnesia” has contributed to the United Kingdom’s referendum outcome, showing quantitatively and qualitatively how the voters’ race mattered in whether a sense of belonging to the United Kingdom and/or the European Union guided their referendum choice. Kundnani is certainly not the first to force a reckoning with race when speaking of the Union’s origin story, but Eurowhiteness propels it further, as a necessary and valuable contribution to the European identity scholarship.

Right and Wronged in International Relations: Evolutionary Ethics, Moral Revolutions, and the Nature of Power Politics

Right and Wronged in International Relations: Evolutionary Ethics, Moral Revolutions, and the Nature of Power Politics

By Brian C. Rathbun

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Recommended by Aslihan Turan

In Right and Wronged in International Relations: Evolutionary Ethics, Moral Revolutions, and the Nature of Power Politics, Brian Rathbun makes a deep analysis of international relations (IR) components and foreign policy behavior through moral theories and social psychology. The book constructs a critical perspective on the limited ability of cosmopolitan humanitarianism studies to cover the place of morality in international politics. The author also reveals the lack of empirical study on morality in IR and wants to fill this gap, as he claims that morality has always played a central role in the perception of threats, conflicts, and international strategies of expansionism.

The method used by Rathbun is word embedding analysis of texts such as speeches before the United Nations and deliberations of American foreign policy officials. He also includes survey experiments on Russian and Chinese public shows, addressing the fact that moral systems have their functional roots in the making of foreign policy and play a role there. The book compares American and Russian foreign policy belief systems and analyzes their respective moral roots. While the motivation to protect and use the “big stick” engenders militant internationalism, the motivation to provide stems from cooperative internationalism. Rathbun also concentrates on Germany as a case study, revealing how morality has transformed and how foreign policy has become bellicose, starting from the time of WWI when morality was binding to that before and after WWII, when authoritarian morality and moral devolution emerged.

Paroles d’Arbres

Paroles d’Arbres

By Ernst Zürcher

Publisher: Presses Universitaires de France

Recommended by Hélène B. Ducros

Ernst Zürcher is a renowned botanist and forest science expert. However, in Paroles d’Arbres, rather than to our scientific rationality, it is to our senses and emotions that he appeals, as he invites us to open up to our relationship with trees. In this original collection of short texts by an array of authors, Zürcher uses a humanistic approach to expose the many ways in which trees matter to people, as he delves into how the different bonds individuals form with the arboreal world are triggered and developed from the time of their childhood through all stages and conditions of their lives. Part reflective journal, poetic fantasy, and environmental critique, Zürcher’s book amplifies the voices of trees, which only some people hear as distinctly as do the contributors featured in the volume. In unveiling some specific relationships people have fostered with trees—whether individual trees or “communities of trees” (i.e., forests)—the essays gathered here help us understand that to fully grasp the treeworld, humans must first become aware of their own emotions and of what that world reveals about humanity, societies, and individuals.

The testimonies in the volume sort out the myriad ways trees are significant to humans; and ultimately the collection seeks to help humans rebuild their link with nature and with their own genealogy in order to forge their (better) future. The book makes clear that the scientific approach gains when complemented by a focus on lived experiences in arboreal contexts, real or imagined, which may help in repairing the modern disconnect between humans and the Cosmos. Listening to and hearing trees thus allows us to unveil the invisible, the unseizable, and the unquantifiable, and enables us to fully recruit our subconscious to rebuild our bond with nature. Trees in turn are the “pillars of our lives,” symbols of time passing, frameworks for the banal quotidian, mirrors for human dances, symbols of special occasions, and sources of dreams and remembrances of familiar places and elsewheres. As we attempt to close the gap between the vegetal and human worlds, trees provide us with inspiration, self-healing, self-realization, strength, joy, and love, but also sadness in the face of decline, decay, suffering, and damage (some of which we suffer and some of which we inflict). At once intimate and introspective and spectacular and charismatic, treeworlds impose a slower rhythm upon our lives, serving as a remedy against restlessness and solitude. Zürcher’s inspiring pages convey that communicating with trees is a two-way process. When seeing trees as spiritual beings with a conscience and envisaging our relationship with trees as a collaboration, we then can connect to invisible worlds below and above, to both the infinitesimally small and the infinite, as well as to worlds that came before us and will come after us.

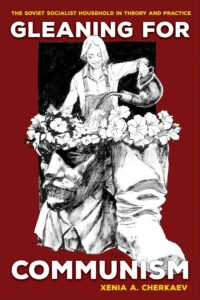

Gleaning for Communism: The Soviet Socialist Household in Theory and Practice

Gleaning for Communism: The Soviet Socialist Household in Theory and Practice

By Xenia A. Cherkaev

Publisher: Cornell University Press

Recommended by Oksana Ermolaeva

Although the social and cultural history of the USSR has profoundly broadened in scope, it has not distanced itself from the collectivist ethics that permeated the newly created Soviet society throughout the “long” twentieth century and made it so different from European polities. All Russian social structures, such as communal apartments and penitentiaries, were imbued with a “collectivist mentality,” which has sometimes been called “barrack mentality.” Thus, the social spaces that first emerged during the Soviet era of so-called “progress from chaos” heavily impacted the development of this new society. Was there a link between the political passivity of the Russian people in the face of an illiberal regime and the communal survival practices on which they had historically relied? Xenia Cherkaev answers this question by providing an ethnographically rich study on the historical evolution of the socialist household economy during the 1930s, 1960s, and 1980s. Through an examination of an array of minute details and fascinating data, Cherkaev demonstrates how the Soviet project became a unique manifestation of long-term “collectivist modernity” and created a society that passively supported an authoritarian regime. In her exploration, she attempts to penetrate into the process by which Soviet propaganda functioned and counteracted reality. She shows that this process relied on images of Soviet society as composed of morally upstanding and generally happy people. These people were self-effacing and friendly, ready to use all available means to help each other in overcoming economic and political hardships—including war.

Published on November 21, 2023.