Translated from the French by Jessica Moore.

These guys come from Moscow and don’t know where they’re going. There’s a crowd of them, more than a hundred, young, white—pallid, even—wan and shorn, their arms veiny and eyes pacing the train car, camouflage pants and briefs, torsos caged in khaki undershirts, thin chains with crosses bouncing against their chests; guys lining the walls in the passage-ways and corridors, sitting, standing, stretched out on the berths, letting their arms dangle, their feet dangle, letting their bored resignation dangle in the void. They’ve been on board for more than forty hours now, crammed together, squeezed into the liminal space of the train: the conscripts.

As the train nears the station, they get up and crush against the windows, press their faces to the panes or rush to squeeze up against the doors, and then jostle for more room, crane to see something outside, limbs tangled and necks outstretched as though there wasn’t enough air, a mass of squid—but it’s strange, if they get out to smoke on the platform or stretch their legs they never stray very far, stay clumped together in front of the steps—a herd—and shrug when people ask where they’re headed: they’ve been told Krasnoyarsk and Barnaoul, they’ve been told Chita, but it always comes down to the same thing: no one tells them anything. General Smirnov may well have said that things were changing, in televised press conferences, that from now on, out of respect for the families, conscripts would know where they were to be posted, but still it seems that once you get beyond Novosibirsk, Siberia remains that which it always has been: a limit-experience. A gray zone. Here or there, then, what difference does it make? Here or there, it’s all the same. And then the kits are handed out and everyone is hustled on board the Trans-Siberian and off they go.

Next come the irreversible rails, laying out the countryside, unfolding, unfolding, unfolding Russia, pressing on between latitudes 50° N and 60° N, and the guys who grow sticky in the wagons, scalps pale beneath the tonsure, temples glistening with sweat, and among them Aliocha, twenty years old, his build strong but his body caught in contrary impulses—torso skewed forward while the shoulders are thrust back, choleric, complexion like mortar, black eyes. He’s posted at the far end of the train, at the back of the last wagon in a compartment slathered in thick paint, a cell, pierced by three openings, that the smokers have seized immediately. This is where he’s found himself a spot, a volume of space still unoccupied, notched between other bodies. He has pressed his forehead to the back window of the train, the one that looks out over the tracks, and stays there watching the land speed by at 60km/h—in this moment it’s a wooly mauve wilderness, his shitty country.

Right up until the last, Aliocha had believed he wouldn’t have to go. Right up until April 1st, the traditional day of the Spring Draft, he thought he would manage to avoid military service, to fake out the system and be exempted—and to tell the truth, there’s not a single guy in Moscow between eighteen and twenty-seven years old who hasn’t tried to do the same. It’s the young men of means who tend to be favored at this game; the others do what they can, and meanwhile their mothers scream in Pushkin Square, in ever-increasing numbers since the soldier Sytchev was martyred, and gather around Valentina Melnikova, President of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers—they’re fearsome, boiling mad, determined, and if the cameras turn up they rush to fit their eager faces in the frame: I don’t want my son to go, and he’s not even a drinker! When reprieves run out, the next option is the false medical certificate, bought for an arm and a leg from doctors who slip the cash directly into their breast pockets, and the families who’ve been bled dry go home and get smashed in relief. If this doesn’t work, and when anxiety has bitten down night after night to the quick, then come the direct attempts at bribery. These can be effective but slow to put into action and meanwhile time is galloping past—investigating the networks of influence within administrations, identifying the right person, the one who’ll be able to intervene, all this takes a crazy amount of time. And finally, when there’s nothing left, when it’s looking hopeless, there are women. Find one before winter and get her knocked up—this is all that’s left to do because at six months a pregnancy will grant an exemption. So there’s no time to lose, the guys get worked up, the women too, not wanting to see their sweetheart leave for military service—might as well say go to war—or coveting conjugal salvation when most of them are single and ashamed of it. Things heat up and soon the condoms are tossed aside, the act is done on squeaking mattresses, and they stick it to the army—they give it the finger.

A girlfriend to save me, that’s where Aliocha was at six months ago—Aliocha who doesn’t have a mother anymore and no money. So night after night he shaved, slicked back his hair with drugstore gel and put on his best threads—snail-like operations, hesitant gestures, little conviction—and went out into the hard night, slowing as he passed the bars to slant a glance inside, into their black and red depths, lingering in the fast-food joints, and ending up in a club with a neighbor younger than him, a twisted little thug who gets in for free everywhere and who urges him to act, voice shrill in Aliocha’s ear, go on, you’ve gotta make an effort, she’s not just gonna fall in your lap, his expert eye scanning the bodies entwined in the spasms of techno, bodies to which Aliocha had his back turned, standing at the bar with his neck sunk between his shoulders, back hunched, nose in the bottom of a glass of whisky he can’t afford. Soon all he did was wander through the giant city where he lived with his grandmother, sitting in staircases, waiting in the courtyards of apartment buildings: he had given up, abandoned the thing that had never begun, this humiliation, this scheme. No woman had ever come to save him, not even the one who walked through the schoolyard in his dreams, fatal and serene, long red woolcoat, black leather gloves, gray fur chapka, blonde hair beneath: a planet unto herself. No, especially not her.

They left Novossibirsk and the enormous central station, high walls of a milky green, tiled hall with the acoustics of a city pool—an icy temple. Aliocha is scared. Siberia—fuck! This is what he’s thinking, stone in his belly, as though seized with panic at the idea of plunging further into what he knows to be a territory of banishment, giant oubliette of the Tsarist empire before it turns Gulag country. A forbidden perimeter, a silent space, faceless. A black hole. The cadence of the train, monotonous, rather than numbing his anxiety, shakes it up and revives it, unspools lines of deportees pickaxes in hand stumbling through swirling snowstorms, stirs the frail shacks lined up in the middle of nowhere, hair frozen to wooden floor planks in the night, dead bodies stiff under the permafrost, blurred images of a territory from which no one returns. Outside, the afternoon is drawing to a close, in a few hours it will be night, but this night won’t be populated with human dreams, Aliocha knows this too. Nothing here is on the human scale, nothing familiar will welcome him here—and it’s this, even, that terrorizes him, this continental pocket in the interior of the continent, this enclave bordered only by the immensity. A finite but edgeless space—consistent, oddly enough, with the representation astrophysicists give of the universe itself—all of this scares the hell out of him.

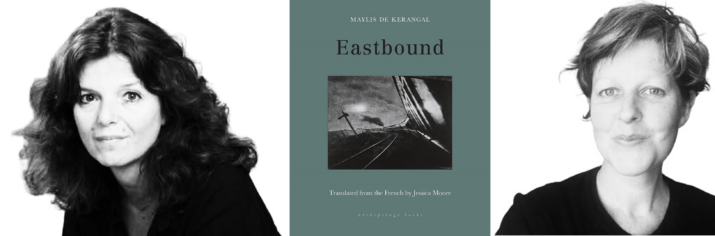

Maylis de Kerangal is an award winning and critically acclaimed author of several books, including Naissance d’un pont, winner of the 2010 Prix Franz Hessel and Prix Médicis; Réparer les vivants, whose English translation, The Heart, was one of the Wall Street Journal’s Ten Best Fiction Works of 2016 and longlisted for the Booker International Prize; and Un chemin de tables, whose English translation, The Cook, was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice.

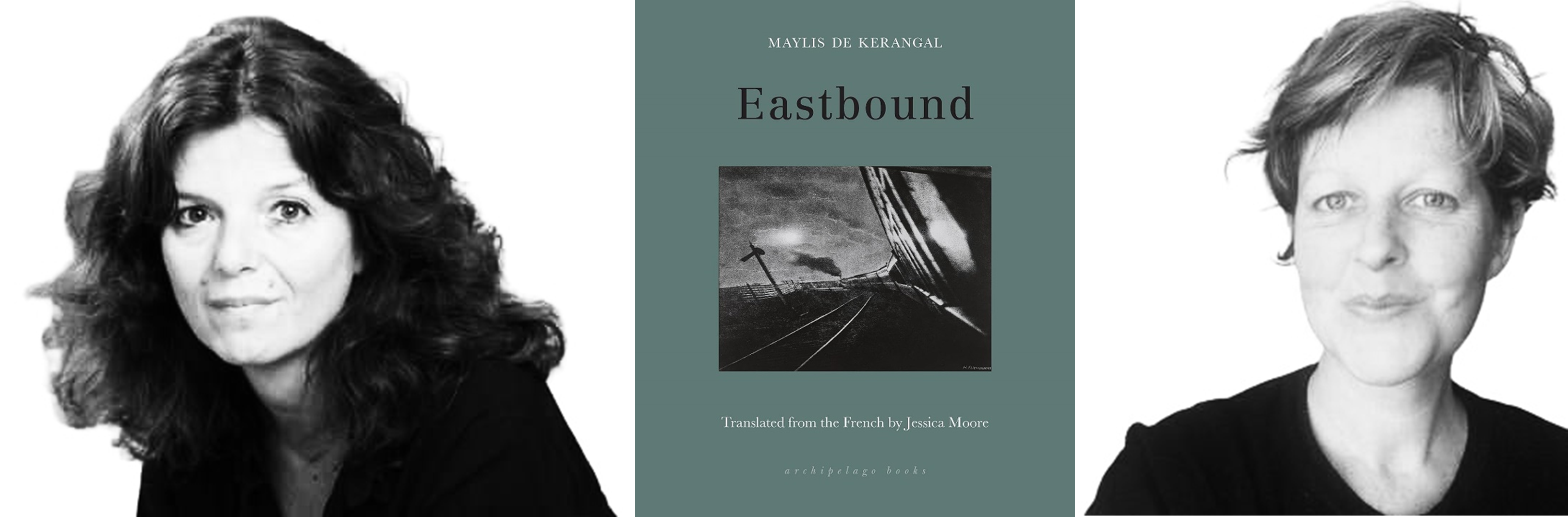

Jessica Moore is a poet and translator She is also a singer-songwriter who plays banjo, piano, guitar, and body-percussion A former Lannan writer-in-residence and winner of a PEN America Translation Award for her translation of Turkana Boy by Jean-François Beauchemin, her first collection of poems, Everything, now, was published in 2012. She lives in Toronto.

This excerpt from EASTBOUND was published by permission of Archipelago Books. Copyright © Maylis de Kerangal, 2012. English translation copyright © Jessica Moore, 2023.

Published on November 21, 2023.