A Collection of Ancient Iranian Seal Impressions at the Institut d’Art et d’Archéologie

This is part of our campus spotlight on Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, with Columbia University.

A collection of ancient Iranian seal impressions (Corpus des empreintes des sceaux de l’Iran ancien—CESIA) has been preserved at the Institut d’art et d’archéologie at the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. It was gathered in the 1960s by Jean Deshayes as part of the work of a French Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) research team, the Centre d’analyse documentaire en archéologie (CADA), which was active in Paris, Marseille, and Beirut until the 1980s. Due to the untimely passing of Deshayes in 1979, his collection had fallen into oblivion for decades until it was recently rediscovered. Since 2017, it has been the object of renewed attention (Antinori 2018). The collection was reorganized and inventoried in a new database and is now kept in a dedicated cabinet, while related archives are being studied. As explained by Mariana Silva Porto and Mathilde Castéran in this spotlight, the archives allow to strictly relate Deshayes to the larger Cylinder Seal Project, despite the fact that he never published on the subject. It is not sure, however, how this collection of (mainly) unpublished cylinder seal impressions is connected to the Cylinder Seal Project, as the latter focused on published material only.

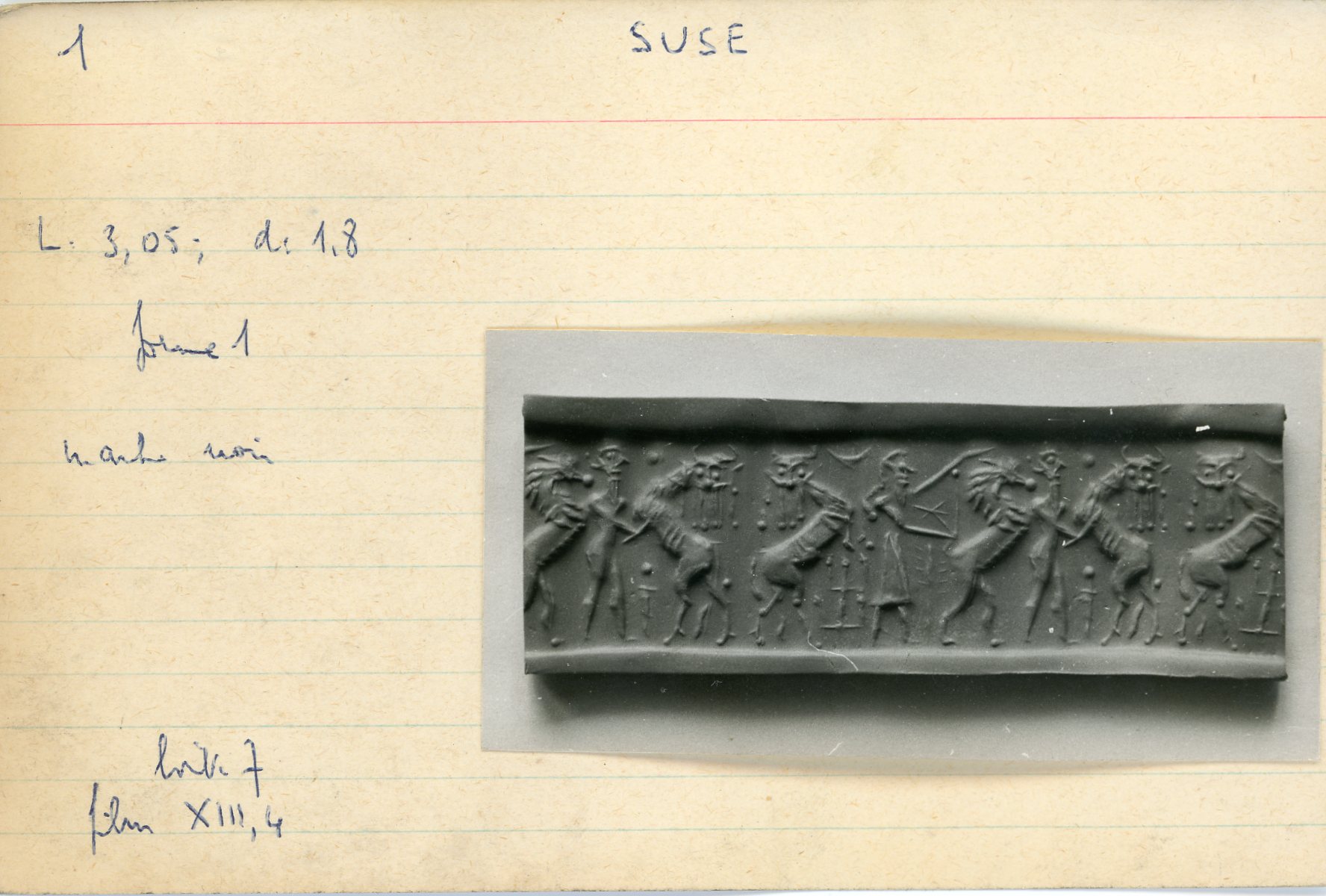

Today, the collection is made of 486 modern clay impressions and 495 hand-written cards with photos and their corresponding negative films. Each impression may be associated with a card since a code appears on both—the code consisting of a combination of a number and a letter—although this coding system does present some inconsistencies and variations. In fact, the system seems to have been changed during the data-recording process. Approximately half of the items in the collection were marked with a number followed by an ascending letter (e.g., 1, 1a, 1b, 1c, etc.), resulting in 239 entries ranging from no.1 to no.15. From no.16 on, the marking on the items shows only a sequence of numbers. However, there are significant exceptions (for instance, no.60 includes letters a to f) and gaps, the most remarkable of which being a gap between no.365 and no.986—the last number Deshayes included in his inventory. This unclear organization has led to various interrogations, which have been left without definitive answers. Considering both the seal impressions and the cards, I proceeded to create a new inventory of the whole collection, using ascending numbers from 1 to 495. The new data inventory was designed to be as close as possible to the sequence set up by Deshayes.

My analysis of the seal collection started with a recovery of the data recorded on the descriptive cards and their integration into a new inventory. Each card bears significant information related to each seal from which an impression was made (fig. 1). Beside featuring the inventory number in the upper left corner, each card refers to the site of provenance (with some important exception), the dimensions (expressed in centimeters), the shape, and the material of the original seal. In the lower left corner, archival information is noted, with the number of the box in which the impression was stored and the reference of the negative film. A photo of the modern impression fills the right side of the card.

The storage of archaeological data in computer databases and their retrieval from such databases are now basic components of modern archaeological research. However, in the 1950s, such endeavor was groundbreaking. In reorganizing Deshayes’s collection of seal impressions, I thus decided to develop a relational database that includes all relevant features pertaining to the pieces of the collection, from material data (size, shape, and form) to intangible data (iconography of the engraved designs). Since the original Cylinder Seal Project focused on iconography, I also wanted to pay special attention to the recording and analyzing of the iconographic features of these pieces. Of course, an extensive inventory could have been easily achieved using a simple and standardized spreadsheet, but I opted for a more elaborate system. FileMaker Pro software offers an efficient tool to create, without any specific programming skill, a structurally complex relational database that includes a great number of tables while keeping a user-friendly layout. This new CESIA database (fig. 2) was made available online thanks to the French Huma-Num portal.[1]

Defining and managing tables and relationships was the core concept used during the data-modelling phase; it was the most demanding task in the process of reorganizing Deshayes’s collection. Entity-Relationships Diagrams (ERDs) are the easiest and most direct way to visualize a database structure. They make it easier to reflect on the nature of each table and to identify how each table relates to other tables. Since one of the main goals of this study was to describe the iconographic repertoire of our collection, a primary objective was to correctly transcribe that repertoire into the structure of the database. However, the idea of creating a single table to describe the entire iconographic repertoire was promptly dismissed. Instead, inspired by the principles of Jean-Claude Gardin’s code, the seals’ iconography was divided into various distinct iconographic categories. This reconfiguration led to the transformation of the database model from a single field into several individual tables. As a result of this process, twelve core iconographic entities were identified, leading to the creation of an equal number of tables and relationships between the main table of the seal impressions and each iconographic entity. In the end, 38 out of the 64 tables included in the database are dedicated to the description of the collection’s iconographic repertoire.

The new database lists the seal impressions. It is stored at the Institut d’art et d’archéologie and offers an analysis of the main iconographic entities represented in the collection:

- Human characters (i.e., men, women, “stick figures,” and undefined people): among 143 impressions, the record shows human characters appearing alone on54 of them; 22 impressions show human in the company of hybrid characters ; 67 show humans represented with animals; and only 7 impressions show humans alongside ornamental patterns.

- Hybrid characters (imaginary creatures such as bull-men and bird-men) are identified in 26 impressions, of which 22 feature hybrid creatures associated with humans, while only 1 impression includes animals.

- Animal characters (including 18 different types of animals) appear on 133 impressions, 65 of which feature animals alone. Ornaments appear in 15 impressions that also represent animals; among these 15, 4 impressions associate animals with humans.

- Ornamental and abstract patterns are divided into 22 simple geometric entities (lines, arcs, lozenges, zigzags, ellipsoidal almonds, etc.) and identified 189 times on 122 impressions, of which 107 are engraved with abstract and geometric patterns only.

The archives associated with the collection firmly establish the Iranian origin of all the seal impressions (see Silva Porto and Castéran in this spotlight). Unfortunately, on Deshayes’ cards, references to the seals’ provenance are quite fragmentary: only 217 impressions bear the mention of a specific site, and 13 of them bear the mention “Delfan,” which, rather than designating a site, is a generic description for one of the eleven counties of the Luristan province of Iran. Overall, only seven sites are recorded in the descriptive cards, all located in western Iran: Susa (162 records), Surkh Dum (24), Delfan (13), Persepolis (12), Tepe Giyan (3), Tepe Hissar (3), and Tepe Sialk (1). The distribution of the sites also seems to reflect the information accessible to Deshayes when he gathered his collection, confirming that the work was conducted no later than the early 1960s. His collection especially lacks items from more recent excavations such as Tepe Yahya and Tell-I Malyan.

Among many other archaeological collections at the Institut d’art et d’archéologie, the collection of ancient Iranian seal impressions not only offers the students of the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne direct access to a large corpus of Oriental iconography but also allows them to be trained in the creation of relational databases, following a traditional computing approach to archaeology that goes back to the mid-twentieth century and is inscribed in the direct lineage of some of the most famous representatives of French archaeology.

Guido Antinori holds a Master’s degrees in Archaeology and in Cultural Heritage and Museum Studies from the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. He is currently a PhD candidate, supervised jointly by the University of Roma La Sapienza and the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

References

Antinori, Guido. 2018. New light on Iranian Glyptic: A study-case of forgotten seal impressions corpus at the University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, M.A. dissertation, available at the Institut d’art et d’archéologie.

[1] https://fms.db.huma-num.fr/fmi/webd/CESIA

Published on November 21, 2023.