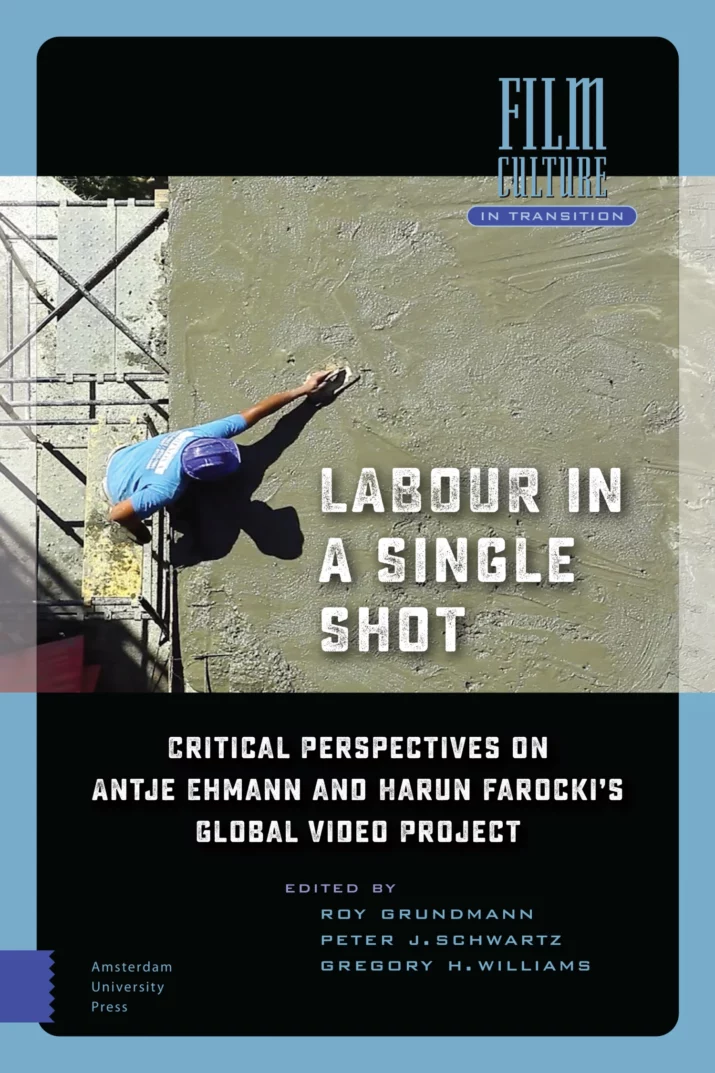

Labour in a Single Shot: Critical Perspectives on Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s Global Video Project by Roy Grundmann, Peter J. Schwartz, and Gregory H. Williams

Labour in a Single Shot: Critical Perspectives on Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s Global Video Project is an excellent example of how focusing on a single film, artwork, or, in this case, a rich, multidimensional media project, can open and expand wide-ranging vistas of inquiry. The book documents and critically examines the conceptual parameters and products of a series of film workshops organized by curator Antje Ehmann and filmmaker/media artist Harun Farocki from 2011 until Farocki’s death in 2014. The workshop takes as its point of departure a rich and multidimensional foundational film, La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon or Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, one of the earliest films shot and screened by Auguste and Louis Lumière in 1895. This movie constitutes a text prescient of the documentary thematics of realism, performance, spectatorship, and, of course, labor. Yet, rather than a return-to-origins seeking to distill cinematic essence from an Ur-text, the gesture to revisit the canonical Lumière short makes Labour in a Single Shot a reflexive “metahistory” of cinema (following Hollis Frampton’s evocative term). First, it is an investigation of the cultural, political, infrastructural, and aesthetic discourses that inhere to cinema as the twentieth century’s global machine for audiovisual display. Second, it invites an extrapolation of the film’s principles of composition for critical analysis into the present digital moment; as Thomas Stubblefield puts it in his essay in the anthology, the project employs a “productive anachronism”: “video is reimagined as early film by participants in the project and then integrated into an online ‘web catalogue’” (333).

Labour in a Single Shot: Critical Perspectives on Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s Global Video Project is an excellent example of how focusing on a single film, artwork, or, in this case, a rich, multidimensional media project, can open and expand wide-ranging vistas of inquiry. The book documents and critically examines the conceptual parameters and products of a series of film workshops organized by curator Antje Ehmann and filmmaker/media artist Harun Farocki from 2011 until Farocki’s death in 2014. The workshop takes as its point of departure a rich and multidimensional foundational film, La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon or Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, one of the earliest films shot and screened by Auguste and Louis Lumière in 1895. This movie constitutes a text prescient of the documentary thematics of realism, performance, spectatorship, and, of course, labor. Yet, rather than a return-to-origins seeking to distill cinematic essence from an Ur-text, the gesture to revisit the canonical Lumière short makes Labour in a Single Shot a reflexive “metahistory” of cinema (following Hollis Frampton’s evocative term). First, it is an investigation of the cultural, political, infrastructural, and aesthetic discourses that inhere to cinema as the twentieth century’s global machine for audiovisual display. Second, it invites an extrapolation of the film’s principles of composition for critical analysis into the present digital moment; as Thomas Stubblefield puts it in his essay in the anthology, the project employs a “productive anachronism”: “video is reimagined as early film by participants in the project and then integrated into an online ‘web catalogue’” (333).

The book, as its subtitle suggests, provides “critical perspectives” on these discourses and the critical work at play in many of the workshop videos, with essays ranging from co-editor Peter J. Schwartz’s history of the earliest images of labor in Europe (from Roman times) through Stubblefield’s and Vinicius Navarro’s essays on the database logics that arise from the web catalogue. Co-editors Roy Grundmann, Gregory H. Williams, and Schwartz’s expansive introduction is supplemented by a fascinating selection of journal entries by Ehmann describing the processes (and frustrations—mainly felt by Farocki) of the workshop process. Four subsequent sections elaborate on major thematic clusters that Ehmann and Farocki’s project inspired: history (covering work, media, and an essay by Thomas Elsaesser, perhaps Farocki’s most prolific English-language commentator, on the dialectic of work and play); poetics (including some of the most insightful readings of workshop videos, especially in José Gatti’s cultural contextualization of videos shot in Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and Lisbon); embodiment (e.g., artist Jeannie Simms connects videos produced in the workshops to those of other contemporary film and media artists who represented labor, and Williams relates handheld tools used in labor to the cameras wielded by workshop participants). In the final section on networks, the theoretical frameworks expand from figures like Walter Benjamin, Sergei Eisenstein, and Siegfried Kracauer, who appear earlier in the book, to Alexander Galloway, Katherine Hayles, and Lev Manovich.

Farocki had earlier made his own response to the Lumière film in a cinema centenary project in 1995, Workers Leaving the Factory, which found echoes of the Lumière film across mainly fiction narrative cinema history, followed by an installation work in 2006, Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades, which showed eleven screens simultaneously in gallery space. If these works are concerned with how labor and workers are imagined across time—including the increasing decline of industrial labor—the workshops are devoted to an examination of the real world, where contemporary multiplicities and complexities often make that world stranger than fiction (or sometimes as tedious as most forms of alienated labor). For the Labour in a Single Shot project, Ehmann and Farocki invited workshop participants to make new films that documented labor following two basic formal parameters of the Lumière film: a single unedited shot of one to two minutes in length. The workshops, held in fifteen cities across five continents—a truly global project—yielded over 550 digital videos by over four hundred artists that have been exhibited in art installation and exhibitions and are also all available online on an open access website. Since 2017, Ehmann and collaborators Eva Stotz, Cathy Lee Crane, León de la Rosa, and Luis Feduchi have continued to hold the workshops in Vilnius, Marseille, Chicago, Warsaw, and Bucharest. The trajectory from single channel film to gallery installation to web catalogue that can be curated for art world exhibition (sites have included two Venice biennales and many museums and galleries) underscores Ehmann’s role as curator and the importance of artistic collaboration inherent to the project’s workshop model. The project required major resources, made accessible through the art world and academic institutions and especially the Goethe-Institut; as former Goethe-Institut director Detlef Gericke (an important figure in initiating and sustaining the project) notes, the project cost by 2014 was over one million euros. The workshops continue to echo what numerous contributors to the book describe as the algorithmic nature of the workshop assignment; moreover, the formal parameters of the original Lumière film impel the (re)iterative quality of the project, which can in theory continue infinitely—as long as the host academic and art world institutions continue to contribute.

The deep process of conceiving and realizing a one-to-two-minute video through workshops is key to grasping the formal challenge that Ehmann and Farocki’s project poses. After all, it would be easy to do an internet search for extant imagery of labor and curate a library of such depictions. As Ehmann’s workshop journals document, the apparent ease of the workshop assignment—anyone with a cellphone can make a single one-to-two-minute video—required Ehmann and Farocki to continually challenge participants to do the work to critically interrogate familiar definitions of labor and think through the basic formal parameters of the video. How to think about composition? (What is onscreen and off-screen? What is visible and invisible labor?). What about image-sound relations? (What is diegetic? What is heard, legible, and/or inaudible?). The key editing decision of where to start and stop the video holds the balance between banal documentation and condensed critical reflection. The balance between aesthetic control and being open to contingency and the aleatory is crucial, as Grundmann argues. Notably, the essays in the book only reference seventy-three videos from the catalogue of more than 550, an indication of how the workshop model, in which process may be more important than product, carries the danger of generating a catalogue of works so expansive that it threatens to overwhelm our capacity to comprehend it.

Many contributors to the book locate the project in relation to traditions of political cinema, especially political modernism (rooted in Bertolt Brecht and Jean-Luc Godard). The index lists a cluster of related concepts (distance/distanciation/defamiliarization, estrangement, ostranenie, Verfremdung) that point to the legacy of twentieth-century Marxist anti-ideological thought seeking to mobilize aesthetic form to liberate consciousness. Others note the legacy of collective production units going back to the 1920s, while Hudson and Zimmerman’s essay points to the more contemporary practice of small-scale participatory community media. Grundmann’s essay locates the workshop videos on a continuity between what he calls the potentially “emancipatory act” of political modernism and the mercantile practices of “prosumer culture,” referring to the massively increased access of image and sound making technologies of the twenty-first century. If the politics of cinematic form and production permeate the project, some of the most interesting possibilities of the project are signaled in essays that take up exhibition and viewing of the project videos—which is, after all, where political effect would be realized. The scale and prestige of Labour in a Single Shot has ensured that over 200,000 people visited the art exhibitions, while countless more have watched videos on the open website. Gloria Sutton notes that free open access “denies the established exhibitionary hierarchies in which the gallery or museum is considered the primary viewing experience and the online sphere functions as a secondary mode” (349). While one can see the videos made at each workshop location on a separate page, on the main web catalogue sorting is limited to three categories: a subject field roughly covering types of work; a short section specifically devoted to “Workers Leaving their Workplace”; and the dominant color palette of the video. This somewhat arbitrary (and playful) database category—as Navarro puts it, “not exactly an orthodox category” (377)—reflects the insistence on aesthetic form in the project. One can imagine numerous other categories that could be inserted (Hudson and Zimmerman suggest gender as a somewhat ignored category of often invisible labor) but the minimalism of categories also invites users to freely explore the ultimately uncategorizable variety of human (and nonhuman) activities in the catalogue.

Finally, the most significant contribution of Labour in a Single Shot as both media project and critical anthology is to make visible and sometimes more legible the conditions of labor in a twenty-first century that has overturned, undermined, or—to use that most odious of management terms—“disrupted” how we work under current conditions of capitalism.

Michael Zryd is Associate Professor in the Department of Cinema and Media Arts at York University. He was founding co-chair of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Experimental Film and Media Scholarly Interest Group. Recent publications include Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada (with Stephen Broomer, Jim Shedden and Barbara Sternberg) and Hollis Frampton (edited for October Files, MIT Press).

Labour in a Single Shot: Critical Perspectives on Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s Global Video Project

Edited by Roy Grundmann, Peter J. Schwartz, and Gregory H. Williams

Publisher: Amsterdam University Press

Hardcover / 410 pages / 2022

ISBN: 9789463722421

Published on July 12, 2023.