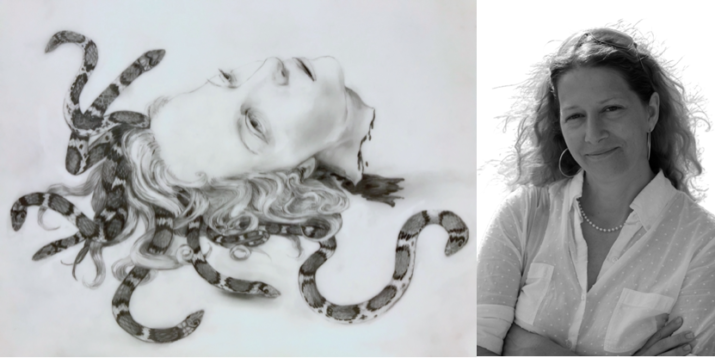

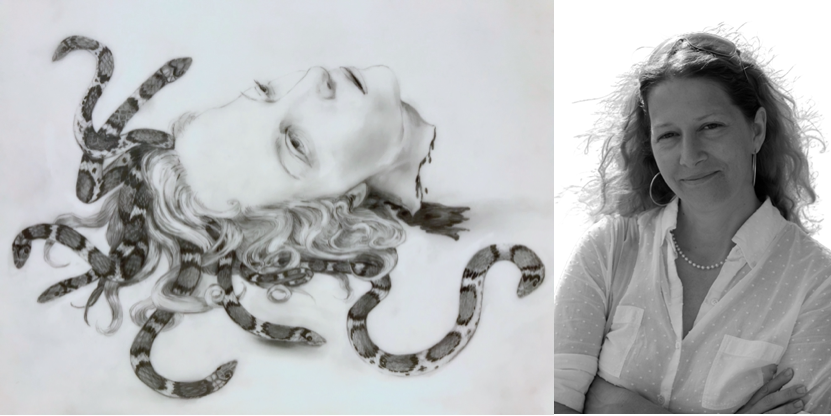

At the intersection of an unlikely trio of characters—opera, Greek mythology, and virtual reality technology—lies Karen Dee Carpenter’s new project “Beautiful Monsters.” This ambitious production recasts the stories of female monsters from Greek mythology in a sympathetic, humanizing light. Mediterranean landscapes provide not simply a backdrop for musical movements, but an immersive experience that challenges these female characters’ alleged monstrosity by placing them in familiar settings. By pairing well-known stories with the resurgent opera genre, Carpenter seeks to capture the interest of new audiences. In this interview, we learn more about the continuing relevance of ancient myths, the power of opera, and the potential of virtual reality productions.

—John Haberstroh for EuropeNow

EuropeNow What is your project Beautiful Monsters about? What has been the inspiration for it?

Karen Dee Carpenter My project, Beautiful Monsters, is a series of short operas filmed in virtual reality (VR) that incorporate live action and animation. My focus is on the female monster-hybrid characters from Greek mythology; I expand and retell the myths from the perspective of these characters. I am primarily a filmmaker, but I have also worked as a playwright, and this experience led me to participate in a musical theater writing workshop with the Nautilus Composer-Librettist Studio. As a librettist, I was asked to write several short works in collaboration with a musical composer. My ideas for these works drew from a variety of sources that included dystopian science fiction, medieval history, and visual art. For a short opera I wrote during the workshop, “Muse of the Underworld,” I was initially interested in the vicious bird-women Harpies of Gustave Doré’s engraving, Harpies in the Forest of the Suicides, used as an illustration in an 1890 edition of Dante Alighieri’s poem The Divine Comedy. While researching the Harpies’ origins in Greek myth, I came across the Sirens, also bird-women hybrids, from Homer’s Odyssey. The mythology surrounding these creatures was narratively more complex and sympathetic, so I decided to create a libretto that focused on a Siren character. The results of this work inspired me to expand on the subject, and I continued to research and develop narratives for a variety of mythological female monsters to create a “suite” of short operas.

EuropeNow I much prefer Homer’s Odyssey to the Iliad, simply because the former is more of an adventure tale and there are so many different situations and characters that Odysseus and his men encounter. How did you settle on this poem rather than, say, Ovid’s Metamorphoses or female heroines in ancient Greek tragedies? In light of the fact that Ancient Greek tragedy and opera have had a productive relationship for centuries, why not choose a character like Medea or a goddess like Persephone?

Karen Dee Carpenter Mythology is a fairly new source of inspiration for me. Homer’s Odyssey, as you mention, is rich with characters, adventures, and conflict. It is a deep wellspring from which I have drawn material that I want to explore in my own work; and, as I continue to investigate mythology, I foresee identifying subject matter from a variety of sources. My choice to focus on female monsters was not a conscious one initially—I simply found monsters to be more compelling than goddesses. Though monsters are often mentioned in the Greek texts, narratives most often present them as the opponents of famous heroes. They have not been written about with much depth; they simply exist as the foil, the “other” that the hero must vanquish. The monsters look abnormal, so they constitute a curiosity, and they can be frightening, or even disgusting. However, in several instances, I have been more empathetic toward them and their circumstances. Since many of these beings were not born monsters but were rather cursed by a god for some transgression, there is room to develop a characterization through a deeper imagining of their plight.

For “Muse of the Underworld” I took information from a variety of texts to meld a backstory for my Siren character. In this fusion, the Sirens were originally handmaidens to Persephone; and when she was kidnapped by Hades, her mother Demeter gave the Sirens wings to go look for Persephone. They were unsuccessful in their attempt to find her and were then cursed to spend their days on the cliffs, using their beautiful song to lure sailors to their death. If a sailor survived, the Siren would die. In my libretto, I relay this history through the life of a single Siren who wrestles with her moral conscience and lack of agency, as she is once again faced with the task of killing the unlucky sailors who attempt to pass her shore.

EuropeNow There is much synergy between your project and recent feminist and queer-positive novels like Madeline Miller’s Circe and The Song of Achilles, Jennifer Saint’s Ariadne, and Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships: A Novel. What role do you see these retellings of ancient myths and your own project playing in public discussions about the ancient and modern worlds?

Karen Dee Carpenter Ancient myths seek to explain the world and all that it contains. The stories are poetic, tragic and often strange, and because they were created and developed in deeply patriarchal societies, they reflect the male psyche and often focus on the violent heroics of men and the brutality of the gods. By changing the perspective, it is possible to utilize these fascinating events and characters in a more expansive way that adds meaning and speaks to a contemporary audience. I have not read all the works you mention, but when I read Madeline Miller’s Circe, I became engrossed in the narrative because I was shown a nuanced and entertaining representation of this sorcerer goddess. Miller established deeper motivations for Circe’s actions and the context in which they happened. I do not believe her novel is a corruption of the original texts, but rather its own work. I feel the success of her book will lead people to explore the source material and will help cultivate a modern appreciation for these ancient works.

With my project, I feel that I am creating something new as well. Through my choice of focusing on monster protagonists and investigating the internal psychology of these characters, I move away from the plot-heavy structure of mythic storytelling. The exhibition format of virtual reality is a drastic departure for how audiences usually experience opera and literary myth, and I think that these shifts have attracted an audience that has not necessarily been interested in or exposed to these subjects.

EuropeNow Some might question the relevance of ancient myths, and some might even argue that opera is also a relic of the past. What would you say to these critics, and how do you make these stories appeal to modern audiences?

Karen Dee Carpenter Opera is becoming cool again. At the 2019 Venice Biennale, Sun & Sea, a site-specific opera composed by Lina Lapelytė based on a libretto by Vaiva Grainytė, won the festival’s top award, the Golden Lion. In that same year, composer Ellen Reid won a Pulitzer Prize for her opera, p r i s m, which was produced by Beth Morrison Projects, a company that cultivates young artists and funds the production of new, innovative operas that attract a more diverse audience. Although many traditional opera houses struggle to remain afloat, there are several indie “upstart” companies that work with significantly smaller budgets, which allows them to continue to move this form forward.

Opera’s grand spectacle aligns with the heroic drama of classical mythology, so it is an obvious pairing. When I began to investigate virtual reality as a filmmaking process, I considered the kind of project that would best utilize this new mode of exhibition. I was struck by the possibility of presenting opera, since my original libretto for “Muse of the Underworld” features a Mediterranean location and a hybrid creature that would be difficult to represent on a conventional stage. If the audience could see this work through VR, it could experience this myth within the story world as the story plays out and alongside the characters. A viewer can fly along with the Siren as she seeks her prey or be on the boat beside the sailors as they plead for their lives. I find the concept of melding ancient myth, classical opera, and emerging technology into a complementary and innovative form very exciting.

EuropeNow Your project uses a virtual reality component, and you film on location in Greece. How do these landscapes shape the stories you are (re)telling? How does the VR medium bring life to your ancient characters?

Karen Dee Carpenter Last Spring, I was awarded a grant from my university in support of my appointment as a Visiting Associate Member at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, where I have been developing the literary and visual design aspects of my project. My main focus has been the writing of the libretti, but I am also involved in preproduction activities such as the creation of storyboards, costume design, and location scouting.

For my initial tests with virtual reality production for “Muse of the Underworld,” I chose to shoot at Calanque d’en Vau, near Cassis in southern France. There, the dramatic, craggy, white limestone cliffs create a narrow inlet that has an “otherworldly” look matching the grandiosity of the mythological narrative. I shot with a 360°camera to obtain a virtual reality “environment” of reference for future phases of this project. For the other operas, I plan to shoot in Greece. I am currently working with the Ephorate of Antiquities in Athens to schedule a shoot in the Temple of Hephaestus in the Ancient Agora in June 2023. Additional shooting locations include the Temple of Poseidon on Cape Sounion, the Temple of Athena Nike on the Athenian Acropolis, and the Ideon Andron Cavern in Crete. I am in the process of applying for the film permits for these sites through the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.

The settings are a key component of the virtual reality “experience” of the operas. I feel that the more realistic I can be with the settings, costumes, and performances, the more captivating the work will be. By avoiding a cartoonish representation, I am better able to engage an audience in the characters’ conflicts and motivations and generate an emotional investment in the outcomes of their stories.

EuropeNow How does Beautiful Monsters fit into your portfolio as an artist, and how has this project pushed your creative abilities?

Karen Dee Carpenter I am deeply invested in telling stories, and I keep experimenting with different ways of doing that. Through filmmaking, playwriting, painting, and now opera and virtual reality production, I strive to understand the parameters of each form, so I can do this storytelling well. Beautiful Monsters is a challenging project that required significant research and collaboration, as well as an understanding of VR production as a complex technological component. All these factors have forced me to expand my knowledge and skills and foster creative partnerships that have allowed me to complete the work.

EuropeNow When and where can the public view your finished work?

Karen Dee Carpenter Beautiful Monsters is still being developed, but the libretto and score for “Muse of the Underworld” is available on my website at http://karendeecarpenter.com/virtual-reality.

Karen Dee Carpenter is a Professor of Film Production at California State University, Northridge and currently a Senior Visiting Member at the American University of Classical Studies in Athens. She is a multidisciplinary artist creating work as a filmmaker, playwright and librettist. Her work has been exhibited internationally and received numerous awards including the prestigious Princess Grace Award.

John Haberstroh is an Assistant Professor-in-Residence of Ancient World History at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He was an Associate Instructor in Classics at California State University, Northridge and a Mellon-Council for European Studies Dissertation Completion Fellow in 2021-2022.

Published on January 31, 2023