Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman.

Hannah and Michel

The trees up and down the esplanade are scraggly and bare. A few kids all bundled up are playing on a grayish stretch, with their au pair watching them. Plenty of Black girls in the mix. Hannah’s alone, like always. The greenish bench she’s sitting on is a bit wet, like it was raining earlier. The sky is just about looming: low, shot through here and there with white. It’s autumn, and a bit sad. Maybe too sad. It makes you want to give up everything. The day before, Hannah got a letter from her mother. Hannah looks at a man in a sailor outfit getting his picture taken in front of Les Invalides. He’s giving his girlfriend a big grin. She’s got to be his girlfriend, or maybe his wife. Her hair is brown and she’s wearing a huge fur hat that’s the same color. Maybe it’s fake fur, Hannah thinks. Maybe. Or maybe not. She’s had enough of that. Why does she have to spend time thinking about these animals who were killed? There are plenty of organizations she can pay to do that thinking for her.

The couple heads off down the rue de Varenne. The man looks back one last time at the gold railing. The woman’s gone and buried her face in the man’s shoulder. The wind is like ice, cutting through, wettish, and it works its way through Hannah’s dark skin. She can take it. She’s been sitting here for two hours, reading her mother’s letter over and over. A letter full of pain. All this pain, Hannah can tell, boils down to one thing: Auguste, a father made a stranger by booze. Can she even remember a single day of him sober, warm? She’s pretty sure not, but deep down, she can’t bring herself to care. Her father not being there is a simple fact that she’s never let herself think on, she’d figured there was no point in it. The letter’s badly written, of course, full of pleading in not so many words, full of love she’s not sure she believes, full of “but how are you?” over and over as if hinting that without her things weren’t all right. Scolding her, really, so her mother won’t be the only one to feel alone, even if she wouldn’t dare to say it out loud. Hannah’s learned about Auguste’s accident, and his being born again. And his new quirks on top of how distant he’d always been. The letter talks about religion. Ma says that it was good at first, this return to God, but now it’s all too much. And at that point Hannah wrinkles her brow. When has her mother ever, just once, had things under control? Not at home, that’s for sure, not while they didn’t have money. Ma says she’s trying to keep up appearances, to make everyone believe that the family is now back together, even without Hannah. The children have grown up. Pauro’s going to take the baccalaureate soon, he’s a man now, after all, a proper man. Ma goes on and on about Rosa, Rosa who’s got her worried, who’s been lost and now found again. Right now Rosa’s going through a hard time, but she’s on the up-and-up. And the mother mentions Pina very briefly.

The letter is full of requests that aren’t requests, she’s pleading for help but not saying it. Come out with it, Ma, what is it you want? Hannah feels uncomfortable, she’s reading things she has to guess at. What is it her mother actually wants? Can’t you just say it straight out, Ma? What is it you need from me? For me to come and save you? I’ve just barely got my head above water! In her letter, Ma asks if Hannah’s business is going well. Yes, she actually thinks Hannah is running a company. She’s completely mental. Hannah’s having trouble breathing. She undoes the knot of her scarf. That helps a little. Running a company. God, if only! No, she’s not running a company. For just a bit over a month, she’s been helping with a business for her lover and boss. Bertrand. He’s not really her guy, there’s no way Bertrand is her guy, much less a husband in the making. No, it’s far too early for all that. They haven’t said “I love you” yet, haven’t even dared to let on that they’re in a relationship.

But for a few weeks now, she’s been working at an art gallery that’s a bit different from the others. One where art isn’t out of reach. Prints of Klein have been selling like hotcakes lately. The store is called Art Popu and its walls are blotchy with rectangles of black and red and every other color. And that’s all that can be seen, rectangles that make no sense to Hannah, but it doesn’t matter, she’s not there to understand them. She just has to sell them, set up small exhibitions, order more Pollocks (prints, of course) that always sell well, she has to deal with pimply teenagers, tall and talented art history students, and on Saturdays there are grown-ups in sneakers or on trendy in-line skates that have to cost a pretty penny. And she has to deal with people who know plenty of things too, who are well-read unlike Hannah herself, the poor thing, who has to learn on the job from Bertrand in between business trips. But, thankfully, the customers don’t know about that. Just like they don’t know that Bertrand is a gallery owner and a publisher, that he has five real galleries in France (plus this fake one that Hannah’s managing), another in New York, and two in Italy, plus a huge publishing house here in Paris. Bertrand must have been a failed painter, he’s so good at picking out the imperfections of the most famous ones: Gauguin, Picasso, and so on. He must have been a second-rate artist, he loves art so much that he almost forgets about real life. Of course Hannah keeps those thoughts to herself. Two days ago, Bertrand went off to Milan. He has to set up the exhibition for a young Italian guy he says is talented and still unknown. At ten in the morning, Hannah left the boutique on the quai Branly. She doesn’t want to deal with anything. She gave the keys to the salesgirl and walked over to Les Invalides. She has a meeting with Michel, a friend, a computer engineer at the place she was working at just before this. He’ll be right on time.

There’s a few more people on the esplanade now, even in this crappy weather. She thinks about Ma again and whispers, look, Ma, look at where I am now. I’m almost a businesswoman just like you’ve always hoped. Her eyes run over the crumpled letter again. After so long, a badly written letter, a letter that makes this girl want to come back, to see for herself how much she remembers of that place, those few nice things. A letter that reminds her that she’s too far away from everything too. She tries to recall the faces of her family and stops on Pina’s. Pina with a look that always struck her as wise, not gloomy, but not happy either, just very clear for a four-year-old. And that’s the last photo she has of her little sister: when she was just four. Thin face, frizzy hair. She almost looked like a little African girl, but without such dark skin. All that is so far away. What’s she become, is she hurting too? Then Hannah remembers that the only child who never got a slap across the face was Rosa. But Hannah doesn’t hold that against her. That’s just how things are. Hannah always felt that children had to put up with parents who didn’t do right by them, put up with those beings who played favorites and don’t do a good job of hiding it. Put up with them because there’s no other way to move on. She put up with it, until she left.

What’s wrong, Ma? I’ll send you some money, don’t worry. Maybe I’ll come back for a few weeks . . . to see if things are okay, to see if there’s any patching things up, mending bridges. Sometimes I half think it’s all been a mistake. Yes, being here. Ma, did you really think I turned my back on you? Do you really think that being so far away wipes away those things we never said out loud? I’m at the other end of the world and I’ve been crying all the while, I’m still crying. We never really grow up, not really. Michel wrote such a beautiful poem, I still remember a few words of it, at least I think these were the words: “I’m ruined myself, like a ghost, by the dead streetlights of Paris.” Michel’s a real poet, he’s all full of wounds. I’ll call you later, that’s the best I can do. It’s a bit late to get into it all, but I’ll call you.

Hannah’s been sitting for a couple of minutes on the bench facing the métro entrance. She can see the top of the head she knows all too well, reddish-brown, starting to get thin, and then the lips come into view, always curling down. The sky’s getting a bit darker. Michel gets to the top of the escalator, carried up while all the others in anoraks run up, even on Saturdays. Michel’s eyes are looking down, like always. And what’s under his feet is ground, gravel. He raises his chin ever so slowly. He’s always got an annoyed look, but he’s not being snobby; he’s shy. Because he feels so small, never mind how tall and stocky his body is. His forehead’s broad, almost like a scientist with brains so big they have to fill this stretch from his brows to his hairline. His forehead has to be ten centimeters. Today his hair’s combed, he’s wearing a shirt under a gray sweater, and he’s also got a windbreaker on. He’s dressed up nicer than usual, but as clumsy as always. Hannah’s never stopped thinking that, that Michel’s unusually clumsy, that his body’s nothing like his personality. Energetic, alert, above average—well above. It won’t be long before he’s a famous writer. She knows it, she just knows it. That’s just how it’ll be, otherwise life wouldn’t make sense. The two of them are so fond of each other. He sees her at last and smiles. At some point Michel let on that every so often he’d smile, just because he’d been reminded that smiles are the least ugly thing that people all have. So sometimes he smiles only so he won’t be too unattractive. Being cynical’s all fine and dandy, but not being unattractive. They give each other a proper hug. Michel likes hugging Hannah this way. She’s so small! She barely comes up to his waist. It’s always awkward for Michel when they talk, he has to hunch down and something in his spine starts hurting.

“It’s always nice to see you, Michel.”

“Oh really?”

“Yes!”

“It had to be nice for you to get out of the office too.”

“Oh, you!”

“Don’t tell me I’m wrong.”

“Okay, okay, yes, I did leave, but you’d have done the same if you were a lowly secretary too.”

“Well, duh.”

“Where are we going?”

“How about Le Divellec? It’s right there.”

Hannah burst out laughing. Of course. He always got those silly ideas in his head.

“Michel, if you want to eat at Le Divellec, your last name better be Mitterrand or Delon.”

“How about Lacan? Or—” He let out a little whistle. “Come on, let’s go.”

Hannah stopped smiling.

“Michel, no. I’m not going there.”

“Why not?”

“It’s not my kind of place.”

“Oh, come on!”

“I’m putting my foot down. I’d feel out of place, and you know it. I don’t like those sorts of spots.”

“You’re wrong. You’re gorgeous.”

“It’s nothing to do with beauty. It’s not about being pretty or smart, it’s about having a nice chunk of money. And you and I don’t have it.”

“You’re a looker, Hannah.”

“Yes, you’ve said that. That’s not the point.”

Sometimes Michel really didn’t make any sense. He hated crowds and gatherings, but he loved packed restaurants, hot ones most of all.

“Okay, fine, Hannah. Come on. We’ll go somewhere else.”

“Thank you.”

They found a French spot with Basque specialties on the rue Saint-Dominique. The restaurant was next to Ed the corner grocer. It was odd to see the prices listed outside, right next to a filthy spot selling bric-a-brac. The restaurant was what Hannah wanted: affordable, not too trendy. Almost unknown. No chance of sighting any news anchors or other bigwigs.

Once they’d sat down, Michel got back up to buy some magazines. Hannah waited a few minutes and then started worrying. Michel always caught her off guard. He might have just gone and gotten back on the métro because he’d forgotten too many things. But Hannah did her best to keep her cool. She waited, she sipped a guignolet. It was sweet and even relaxing. Her legs were already starting to loosen. She liked this feeling. And then, finally, Michel turned up again. She could have wrung his neck.

“Don’t do that again, Michel.”

“Just you watch and see, sweetie.”

“But why?”

“It’s because you picked Bertrand. Such an artist, such a gentleman, such a dickhead.”

“Oh, stop it. It wasn’t some choice between the two of you. I like you, Michel, but as a friend.”

“As a friend, my ass.”

Hannah gave him a look.

“Okay, fine, I’ll stop.”

“What did you end up buying?”

“Marie Claire, Féminin, Actuel, and . . . Penthouse.”

Hannah smiled again. She was thinking about how Michel was like an endangered species. Everyone loves them, but really, that’s not the only thing people could do about them. Still, it’s not like they live right there. Michel doesn’t have a TV, he doesn’t listen to the radio, he doesn’t buy Libé or Le Monde. It’s not that he doesn’t care about the news, about the world around him, because that’s what he gets his ideas from, but he doesn’t want to hear it all, or read all these rundowns from journalists who always have and always will have ego issues. So he reads the letters to the editor. That way he knows what’s going on: rants and sob stories from these “common women” sharing them with him.

Michel orders a whiskey on the rocks, has a smoke. They order almost without thinking. Get some confit of duck and then some foie gras with port-wine sauce. What they do care about, a little, is wine, the best kind, or so Michel says. Hannah’s never heard the name of this one, but she lets him pick. They talk, she asks Michel to lay it all out. What’s he really fixing to do? Any news about the manuscript he sent out? What’s happening with those executives who don’t know their heads from their asses? Michel says that he’s waiting for them to call him or write him. It’ll work out, Michel, just be patient. He’s working on something else now. Already? About what? Michel says, “It’s about you, Hannah,” and of course she doesn’t believe him.

“You know, Hannah, if you keep on not believing, not believing in people and not believing what they say, you’ll end up like Bernier, you know, that woman in accounting. Just like her: old, ugly, all alone.”

“That’s not very nice, Michel. All I was saying was that I didn’t believe you. Because I don’t know. I don’t get it. Out of the ordinary is what you are, you’re so different, it’s not possible. And then you go and say I don’t believe in anything. Look at yourself! You cross out everything you write. When we finish reading you, we cry because we think there’s nothing better we could spend our time reading. And then you destroy it all. That makes you the worst of us all, Michel. You’re worse than I am!”

“You’re wrong, Hannah. I cross it all out because we need more, because we have to believe in more things, in life if nothing else. You know it. Be fair. I’m telling you that I’m writing about you. And I think that’s the best proof of all.”

Michel didn’t say “of my love.” There are moments when there’s no going any further in your thoughts. It’s a dead end, or an impasse, or, here, pure modesty.

An old lady to their left looks at them warmly. It looks like they’re having themselves a little squabble. It’s sweet to watch.

The food comes. The two of them dig in, quiet, embarrassed. Michel went too far. It’s like he confessed his undying love. I didn’t think about Bertrand today, she realizes. She smiles.

“And how are things with Bertrand?”

“Funny you should ask, I was just realizing that I haven’t thought about him today.”

There’s almost a gleam in Michel’s eyes.

“Oh, I shouldn’t have brought him up then! You’re killing me, Hannah. He’s no monster, but he doesn’t love you the way he ought to.”

“What would you know about it?”

“I just know, okay! What time is it where he is? Has he ever taken you on a trip, even once? You know what he’s doing with you? He’s using you to make himself look good here and there. You’re just his exotic little arm candy on Fridays that he shows off at exhibition openings for cool Black artists. He gave you his store, and honestly ‘give’ isn’t the right word. The store isn’t anything special for him. He’s got plenty of actual galleries, doesn’t he? Ones he actually deals with? And there are stuck-up bitches at every one.”

“You’re quite the know-it-all, Michel.”

“What, you think I’m just going to let you be fooled?”

“You’re jealous, that’s all.”

“Oh, jealous, jealous, jealous. Open your eyes, Hannah. You said no to Divellec because you were scared. What if we’d gone? Boom!”

“Michel. Stop it, will you?”

Hannah isn’t hungry anymore. She pours herself some more wine. “That’s low of you, Michel. I’ve never seen anyone go this low with me.”

She could have yelled. Maybe it’s the alcohol, maybe it’s the stress. Ever since she started working by the quai Branly, she’s only been getting four hours of sleep a night, sometimes less. She’s doing everything she can to make Bertrand happy. To blow his socks off.

Michel’s just blinking. That’ll teach him. Everyone else in the restaurant is staring at them.

“I’m sorry, Hannah. I’m sorry.”

She’s ready to give him a piece of her mind.

“I’m so sick. Sick of not being happy. Sick of not having anyone to love. Bertrand is sixty. Is that so hard to believe? And I’m twenty-five. He’s had three wives already. They’re all classy women. They’ve all been to art school, and finishing school before that, they’ve all got huge stuck-up-bitch eyes. And all I’ve done is go to business school and not even a fancy one. I was on scholarship! Come on. Yesterday I got a letter from my mother. I have a mother, you know, and a father too. And a shitload of brothers and sisters. I’ve never seen the youngest one, not even in pictures. Her name is Moïra, but what do you care. I’m just putting that out there. Anyway, my mother. I got a letter from her last night. For the first time she actually wrote to me, and I felt like, back there, things are actually worse, and my whole night’s been a mess. I wasn’t much better this morning. Sure, we all have problems with our mothers. I’ve had my share too. When I was a kid, I couldn’t see why she didn’t dump my dad who was a big old drunk. I didn’t get it at all. And then while I was waiting for you, it all clicked. She never left him because she’d sacrificed herself, forever, for a man, for her children. She really was sure it was the right thing, that it was what she was supposed to do. And I realized that I love her, I love that woman. I still do. She’s never had a hug to spare for me. I was the one who helped with everything around the house because she had to deal with rug rat after rug rat like flies in the soup. But she didn’t know that I had to take care of my father too. I had to deal with him. You listen here. I had to do things nobody should ever have to do. Horrible things. I hated myself for years, I hated that man. I had to handle him on his nights, like a trained woman who’s learned everything about her man down to the last little thing. Who knows what it means when he slows down, when he’s tired. Who figured out how to get those horrible moments, those disgusting moments that were somehow freeing too over with as quickly as possible for him and me. That I had to make sure he stayed happy so he didn’t feel lonely because Ma was getting pregnant over and over and over. I was eight! While I was waiting for you, I was rereading her letter and then I thought: You asshole, where were you when I needed you? Where? Where did you want me to be? Where did you want to find a woman like that? She had so many kids, she had so many bruises after every single weekend, some worse than others, she had black eyes, cracked ribs . . .” Hannah took a breath.

“Booze did all that, tore apart that family. Destroyed me. You know, deep down, what you want Bertrand to be like for me. He can’t reach me, nobody can reach me anymore, Michel, it’s all over. Are you scared for me? It’s too late for that, I died a long time ago. It doesn’t matter if it’s Bertrand or you or someone else, that doesn’t change a thing . . . Anyway, the letter. I finally got it when I remembered that my father did things to me that would break any girl, I got it when I thought I might be clinging to Bertrand, I think about clinging to people a lot, so I can forget. Even booze doesn’t help. It’s wrong to say that people drink to forget. Booze forces you to think about yourself. To look at your life like it’s a rotting belly button. It’s disgusting, but there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s almost nice to look at death and every day you have a drink you think about it again. Every single day. So you can find the one big hole in your existence, so you can daydream a bit too. I drink, but I can’t forget. And there you have your answer about Bertrand and the store. They’re how I deal with it. Fine, Bertrand’s just a lover. We have sex every day, every night, all the time, whenever we can. That’s how I manage to forget a little, and I actually do forget, yes, I forget somehow.

“I hated my mother. Sometimes I was sure she knew it. I was mad at her for squeezing out kid after kid. I hated it when she was pregnant. I still hate her, but I know she needs me right now. And it can’t be easy for my little sisters. You’re giving me all this hassle about Bertrand and about yourself, dropping hints about liking me. Thank you so much, Michel, but do you really think that’s going to make things all better for me? And then you accuse me of not believing in anything. You’re wrong. I believe in redemption, some kind of redemption. Not the Christian kind, for the whole human race. The kind that’s just a single person who’ll come and pull us, my family and myself, out of this. I’m waiting for that pure soul. I’m waiting for redemption for myself. My mother and father too. Yes, for them too.”

She takes a breath and says it again: she hates pregnancies. Then she breaks into nervous laughter, a little hysterical laugh.

Michel’s crying too. It really does a number on Hannah, seeing a man cry so quietly, no disgrace or hatred or fuss to it.

“You’re the only one who knows all this, Michel. It’s a lot.”

And then a gulp of wine, still a bit bitter.

It’s already five in the afternoon. Michel hasn’t noticed that the restaurant’s empty,

Hannah either. The owner is silent, at the far end of the room, not even moving. Michel leaves him a fat tip and says thanks for not trying to kick them out. The hulking figure says a few nice words, with that Basque accent of his. “Hope to see you again soon,” he says, and he watches as they walk out and leave.

It’s almost night. The rue Saint-Dominique’s empty, the metal shutters covered in graffiti are pulled down over the Clef des Marques storefront, leaflets are fluttering over the sidewalk. Hannah’s tottering. They stop at the corner store for some Marlboros. Across the street is a wine shop. They get four bottles of chardonnay, Hannah’s favorite.

“I don’t want to go back home, Michel.”

“I know. And I don’t want to see you go. Not ever.”

Clumsy Michel’s holding her by the waist. He’s really too tall.

They call a cab to take them to the rue de la Convention in the fifteenth, where Michel has a two-bedroom. The main room’s huge, stark: just a couch and a bookcase.

He flicks on the kitchen light and leaves the door open. A rectangle of light between two worlds—one full of darkness, one full of light. They pick darkness.

“I’m forty, Hannah. Not sixty. I’m not some highfalutin aesthete. I don’t travel much. I’m a bit claustrophobic. I don’t measure up against your Bertrand. But I’ll keep talking about it. Because I’m jealous, after all. I saw you that day when you started working at Mister Timid’s, looking so uncomfortable. You were so pretty and I was already head over heels for you. Then you walked over to me.”

“That’s true, I did. I was the one who said hello. How funny. You know I’m not much for small talk. But it was different with you. It’s always different with you. It’s never like with the others.”

Hannah has her feet up on the coffee table; she’s already pulled off her ankle boots, her turtleneck. He’s turned up the heat. She’s still got her tight T-shirt on.

“I’ve never gone out with friends. Isn’t that weird?”

The wine’s there in glasses that he’d just washed a minute ago and then set by their feet.

“Do you ever tidy up, Michel?”

“I’m a guy.”

“Look, stop talking about Bertrand like that. Things can change in just an hour.

Sometimes all it takes is a word, a thought, that meant everything yesterday but nothing today. Or the other way around.”

He’s put on some music. A jazz compilation. Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, a few others.

“Do you like jazz, Michel?”

“Not really. It’s just to set the mood. To give me a bit of a personality when I have girls over.”

“Gee, thanks.”

“No problem whatsoever.”

They have a bit of a laugh. It’s almost ridiculous. It’s lighthearted.

“Tell me more about you, will you?”

“Sure,” Hannah says, and there’s no dwelling on why he’s asked, how wise or unwise any of this might be. Right now, she’s feeling relaxed, not so weighed down. Maybe this was all the right thing for her to do, who knows.

“In a few minutes, Michel, we’ll have sex. Then you’ll have gotten your fill of me. My body, my past. Maybe tomorrow you’ll kick me out. It’s no big deal. Those things happen. I’ll give this a try. I’m sleeping over tonight. In the morning, if you suddenly feel like you’re all out of sorts, if I see that you’re looking at me different, then you’re just as stupid as all the others. But don’t worry, don’t feel guilty, just remember, I died a long time ago.”

The minutes go right by. They look each other over. He rests a hand on her neck and pulls her close. She smells his sweat. Under his shirt, she feels some hair. Kisses, sucks on his skin. Reaches for his fingers and palms. He shuts his eyes, all of a sudden he’s small, weak, at this girl’s mercy. He sit down on the floor, takes in the naked body lying on the sofa. She’s let down her hair and she’s practically begging him. He strokes her, holds his breath over her crotch and her lips. Slips in slowly, differently. His tongue’s forgotten all these things he thought mattered. So has the rest of his body. His tongue’s got something new to do, it’s nothing to do with pleasure, it’s about marking his territory, nothing selfish to it, just wanting to do her good, needing to give her back some life.

She could have yelled. When he takes her, inside it’s not just hot and soft. He’s thinking that, of all the women he thought he’d loved, none of them had such a perfect body. The way she’s squeezing him, pulling his penis in—there’s something delicious, needy, hungry to it.

Men aren’t something that’s been missing from her life, but still, even with Bertrand, she’s never felt pain like this, never felt fulfilled like this. Pain. There are too many things holding the two of them together. They didn’t bother with condoms. Love, true love, means they’d be willing to die by or with each other.

Michel always figured he was a second-rate lover, that he had nothing on those porn stars men like him living all alone measured themselves against. He didn’t have a body like theirs, muscles like theirs, he didn’t reckon he could come anywhere near them. But Hannah lets herself go with him, like no other woman ever had. And she doesn’t seem to be faking it.

Now he’s on his balcony. Completely naked. He’s smoking, he’s freezing, but he barely feels it. It’s November 25. In a month it’ll be Christmas. He dreams that he’ll finally have someone to give a nice present to, someone to wish happy holidays to. He goes back into the bedroom. Hannah’s asleep in his huge bed that he always thought was too chilly. A peaceful face. He sits down and touches her ass, those rounded dunes. She’s like a princess. My princess, he thinks, my island princess. With his tongue, he wakes her up. It’s so good. Hannah feels her body shaking. Inside her there’s a huge hole, the kind happiness leaves behind sometimes, a bitter happiness because it’s so hard to believe. She lets go. She lets herself moan.

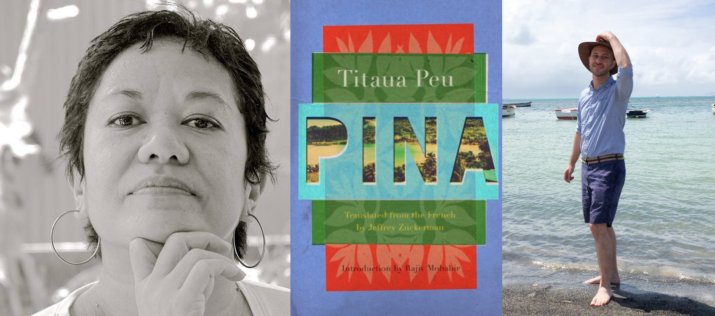

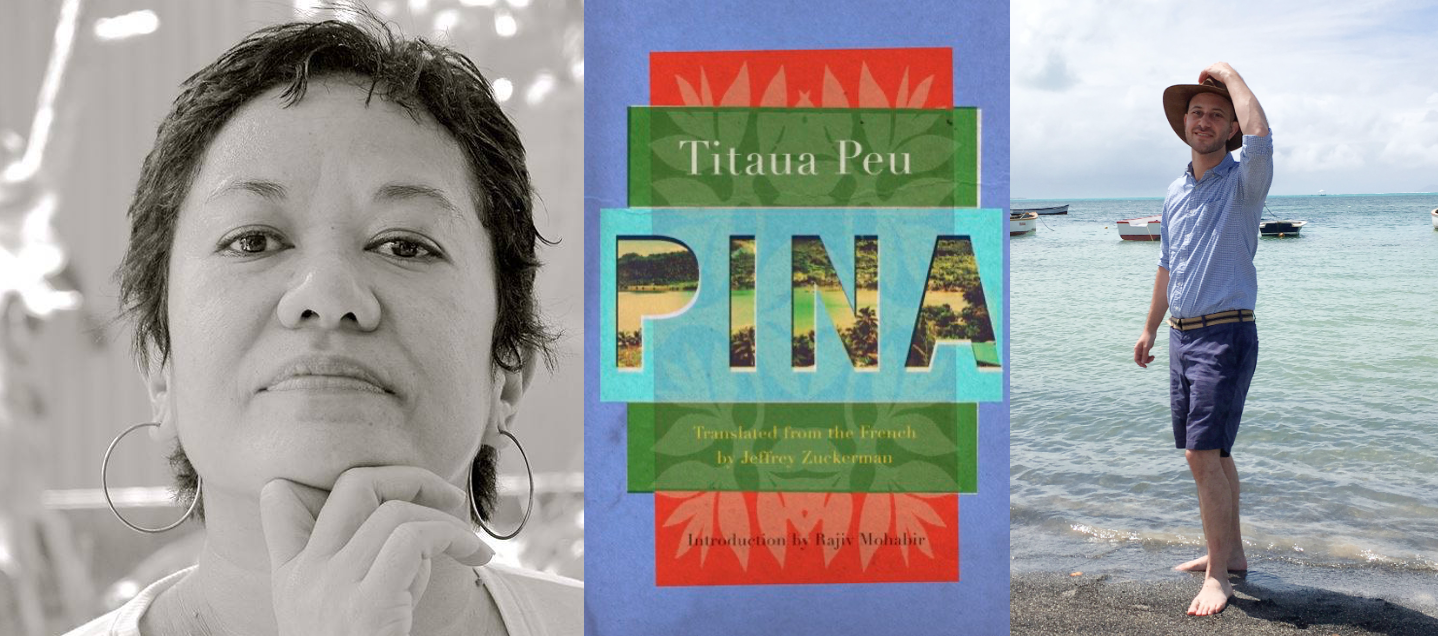

Titaua Peu is a Tahitian author known for her politically charged, realistic portrayal of the effects of colonialism on contemporary Polynesia. Peu’s unsparing first novel, Mutismes, was published in 2003, sparking immediate scandal and making her the youngest-ever published Tahitian author at age twenty-eight. Pina was awarded the 2017 Eugène Dabit Prize, a first for Polynesian literature. She currently lives in Tahiti where she serves as the general manager of the municipality of Paea.

Jeffrey Zuckerman is a translator of French, including books by the artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Dardenne brothers, the queer writers Jean Genet and Hervé Guibert, and the Mauritian novelists Ananda Devi, Shenaz Patel, and Carl de Souza. A graduate of Yale University, he has been a finalist for the TA First Translation Prize and the French-American Foundation Translation Prize, and he was awarded the French Voices Grand Prize for his translation of Pina. In 2020 he was named a Chevalier in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. He currently lives in New York City.

This excerpt from PINA was published by permission of Restless Books.