Translated from the Hebrew Yardenne Greenspan.

Shauli came home that weekend. I was astonished when he appeared in the doorway with his uniform and rifle. I hadn’t seen him in two weeks, and tried to complete the missing pieces with a single look. I treated him like a prince,doing my best to be the perfect mother. I cooked stews (I barely cook for myself—when he isn’t around I mostly eat fruitand vegetables, yogurt, or some eggs at most), filled the fridge with his favorite foods, bought a challah for Shabbat,changed his sheets, and cleaned his room. He’d lost a lot of weight in the two weeks he’d been away. His hair was short,which suited him, and his face, neck, and arms were so tan they were almost black.

We sat at the dining table, I served him more and more food, and he told me about his friends, his commanders, the shooting ranges and morning formation. He’s fine, I told myself, no cause for concern.

The channels of communication are open and his eyes aren’t crying for help. I memorized the names of his new friends, just like I used to when he was in kindergarten. I nodded and smiled, riveted, listening as carefully as Icould. Nothing existed beyond his face and his voice. Then he called up his friends, changed into a bathing suit, and grabbed his surfboard from his room. I asked if he wasn’t exhausted. He said he was, but he didn’t want to sleep theday away. After he left, I unpacked his things and carried the laundry bag over to the machine. Standing in front of thespinning clothes, I thought, The boy is back, everything is fine, he’s healthy. For a moment, the cloud of worry hovering over my head scattered.

In the afternoon we walked over to my father’s. He had ordered food from the last surviving Jewish restaurant in town—chicken soup, roast beef, and half a roast duck. He watched Shauli pick up a spoonful of chicken with noodles, and asked, “How are your feet? I had so much trouble with blisters and chafing when I was in the army. I remember itmade my life a living hell. The boots were so heavy.”

“I’m fine,” Shauli said, smiling at his grandfather. “They gave us lighter shoes. And I’m having no problem with the physical activity. I’m even helping others.”

“And how are your commanders? Are they very tough?” Dad asked.

“Yes,” Shauli said, his mouth full. “They’re tough. You can’t joke around with them. One time, during formation, Ionce answered ‘okay’ instead of ‘yes, sir’ to a sergeant and had to run around the entire base with a full pack on my back.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “By the end of basic training, they’ll be your friends. It’s just a game they’re playing withyou.”

“A sadistic game,” Dad commented, “and likely completely unnecessary. If it were up to me they would have stoppedthat kind of thing a long time ago.” But no one asks you, Dad, I thought. You’ve never tried to change anything, andthe military can’t just give up this power dynamic, it’s part of the deal.

“Are they letting you sleep at night?” Dad asked, sticking a fork into a browned duck leg and placing it on Shauli’s plate. He poured himself some red wine, even though he wasn’t allowed to have it, and I didn’t say anythingbecause his face was very pale and his days seemed numbered anyway.

“In principle we get six hours of sleep,” Shauli said, “but in practice it comes down to less, because we have toshower and all that. We don’t always get hot water.

And sometimes we have guard duty at night. We’re tired all the time.”

Dad gnawed on the other piece of duck, crushing the bone between his teeth. He didn’t like the military and had badmemories from his own service. Once, when I was a kid, he told me his commanders had picked on him because theythought he was a smart-ass.

“Your mother has good connections in the army,” Dad said, and I could tell by his voice he was trying to provokeme. “Maybe she can talk to someone and get them to let you sleep a little more.”

“You know I’m not going to do that, and Shauli doesn’t want that either, it would only embarrass him,” I retorted, getting pulled into his ruse.

“You’ve advised generals and colonels about how to get the most out of simple soldiers,” Dad hissed. “You’ve translated capitalism into military terms, just like psychologists who work for factory owners do. But soldiers don’thave a workers’ union, so the army can do whatever it wants with them, even send them off to die.”

“Is this really necessary?” I murmured, astounded by this burst of aggression.

Dad raised his eyes, which saw all—he knew how to paralyze me with those eyes—and said, “You’re right, Abigail. It’s a shame to spoil this delicious food.”

Shauli buried his face in the plate and said nothing. He loved his grandfather very much, and the friction betweenus wasn’t his problem, yet I was secretly angry with him for not coming to my defense, for always remaining neutral.

When I told my father, at age seventeen, that I’d applied to psychology studies as part of my military service, he tried totalk me out of it. “It’s a dangerous combination of psychology and army,” he said. To this day, I can hear his measuredtone. “It’s the greatest contradiction imaginable. The military is a totalitarian cohesion that erases the individual, and inour profession the individual is all that exists, and your loyalty toward them must be absolute. What are you hoping toachieve?”

I had no idea what I was hoping to achieve. I knew I wanted to be like Dad, better than Dad, and was looking for thequickest way there. I had no patience to wait until my service was over. I was still no match for Dad when it came to abstract ideas. He’d read all the English and French books that filled the shelves of his clinic, and I wasn’t even out of high school yet. But I stood strong before him, not backing down, knowing intuitively that this was the right call. Hisresistance only reinforced me.

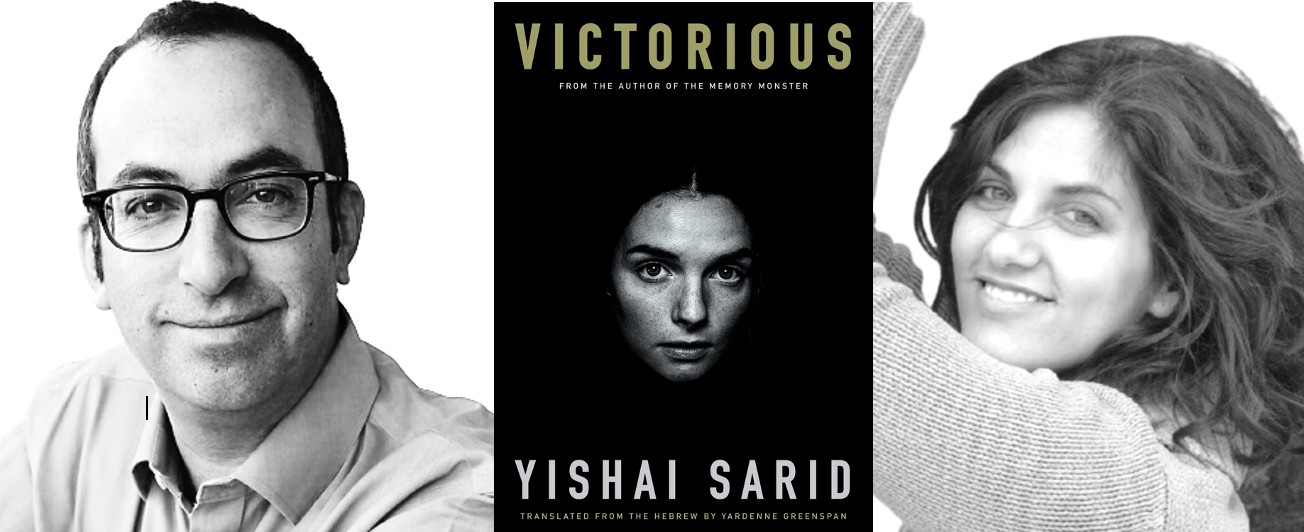

Yishai Sarid was born and raised in Tel Aviv, Israel in 1965. He is the son of senior politician and journalist Yossi Sarid. Between 1974–1977, he lived with his family in the northern town of Kiryat Shmona, near the Lebanon border. Sarid was recruited to Israeli Army in 1983 and served for five years. During his service, he finished the IDF’s officers school and served as an intelligence officer. He studied law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. During 1994–1997, he worked for the Government as an Assistant District Attorney in Tel-Aviv, prosecuting criminal cases. Sarid has a Public Administration Master’s Degree (MPA) from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1999). Nowadays he is an active lawyer and arbitrator, practicing mainly civil and administrative law. His law office is located in Tel-Aviv. Alongside his legal career, Sarid writes literature, and so far he has published six novels. His novels have been translated into ten languages and have won literary prizes. Sarid is married to Dr. Racheli Sion-Sarid, a critical care pediatrician, and they have three children.

Yardenne Greenspan is a writer and Hebrew translator. Her translations have been published by Restless Books, St. Martin’s Press, Akashic, Syracuse University, New Vessel Press, and Amazon Crossing, and are forthcoming from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Yardenne’s writing and translations have appeared in The New Yorker, Haaretz, Guernica, Literary Hub, Blunderbuss, Apogee, The Massachusetts Review, Asymptote, and Words Without Borders, among other publications. She has an MFA from Columbia University and is a regular contributor to Ploughshares.

This excerpt from Victorious was published by permission of Restless Books. Translation copyright © 2022 by Yardenne Greenspan.

Published on May 18, 2022.