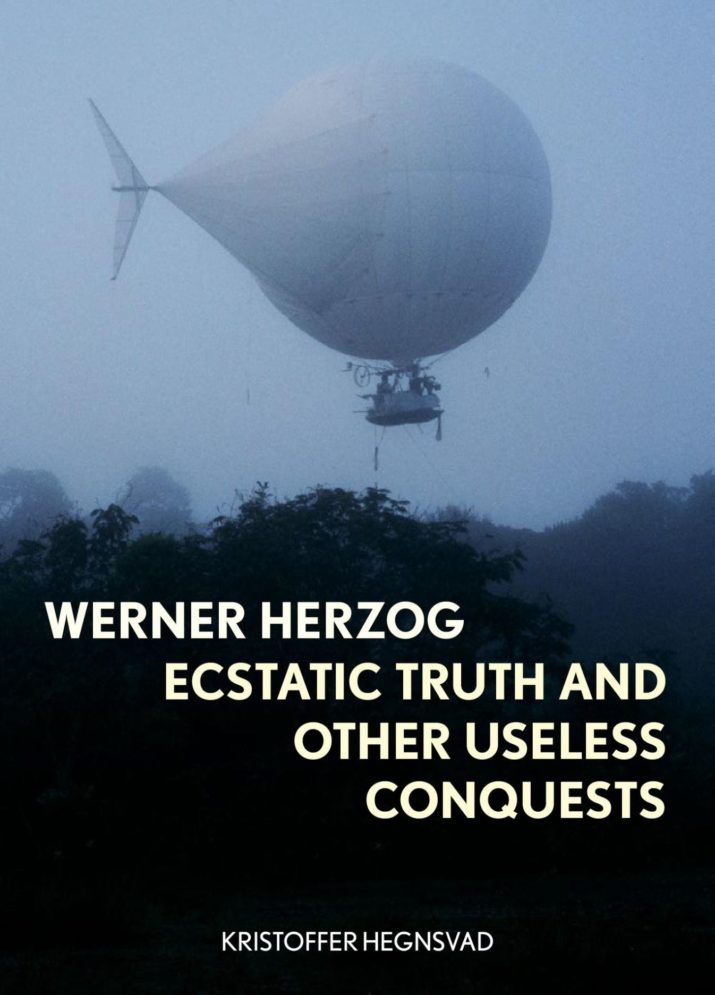

Like the filmic oeuvre of German director Werner Herzog himself, Kristoffer Hegnsvad’s study is difficult to categorize or even summarize. First published in Danish in 2017 and inspired in part by Hegnsvad’s own filmmaking and journalistic career, the starting point for this fascinating and illuminating work is the author’s encounter with Herzog when in March 2016 he participated in one of Herzog’s near-legendary Rogue Film School residential workshops. He readily admits that he is a fan of Herzog’s cinema, and it is apparent that this work is something of a labor of love. Interwoven with personal anecdotes and quotations drawn from a range of interviews conducted with Herzog over the year, Hegnsvad’s volume does not present us with a conventional film studies account of Herzog’s wildly eclectic career. Instead, drawing upon the German director’s many philosophical musings, Hegnsvad analyzes key moments in a range of Herzog’s films, from the earliest in the late 1960s to the most recent releases, to shed light on Herzog’s relentless search for moments of “ecstatic truth” in film.

Across the seven chapters of his study, Hegnsvad expounds on a series of key, interlinked Herzogian terms and filmic approaches, such as “ecstatic truth,” “chronicler,” “the truth of accountants,” “the useless protagonist,” and the “conquerors of the useless.” Frequently, taking as his chapter titles terminology from the book of Herzogian truisms, the author investigates Herzog’s film images, cross-referenced against a broad array of seminal philosophers and critical thinkers: Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and even novelist Bruce Chatwin, to name but a few. Here, too, critical vocabulary is introduced and held up to Herzog’s films: from Deleuze’s “any-space-whatever” and “rhizomatic storytelling,” via Adorno’s concept of art as “non-identical” with the empirical world, to Bruce Chatwin’s “ethic of walking.” Hegnsvad presents compelling readings of Herzogian moments (rather than offering comprehensive analyses of films in chronological order) and establishes a coherent sense of order out of the apparent chaos of Werner Herzog’s spectacular career.

There are, certainly, moments of chronology imposed on the study: Hegnsvad considers the impact of Herzog’s fatherless childhood in post-war West Germany, for example, as well as the influence of Germany’s Weimar directors on the young filmmaker. He examines Herzog’s connection to, and rejection of, the 1962 Oberhausen Manifesto, which gave rise to the New German Cinema movement, and repeats the well-known anecdote that Herzog launched his career after stealing a camera from the Munich Film School. He references—and analyzes—the significance of Herzog’s 1999 Minnesota Declaration, as well as the notorious boot-eating “happening” captured in Les Blank’s short film Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe. He peppers his text with quotations and anecdotes from various interviews and published essays over the course of some seven decades of filmmaking, all to illustrate the single key thesis: “The endgame of [Herzog’s] battle is to expand the colour spectrum on our shared palette of images and languages, so that we have more nuances to choose from when we paint our self-image as individuals and as a society” (134).

As he develops his thesis, Hegnsvad considers many of Herzog’s best-known films, along with some that are rather more obscure or even controversial. He recognizes the eclectic nature of Herzog’s filmmaking approach—observing wryly that “if Herzog doesn’t meet the auteur criteria, nobody does” (43) whilst simultaneously conceding that every film defies simple genre definition. He notes how documentary and feature filmmaking styles collide and overlap in the obsessive project that results in Fitzcarraldo (1982), declares the protagonist of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) “the ultimate outsider” (74), and dwells on the futility of revolt in films such as Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), Woyzeck (1979), and Stroszek (1977).

Central to Hegnsvad’s thesis is a reading of Herzog’s mistrust of “the truth of accountants,” which is the director’s term for society’s desire to categorize, to label, and to reduce the complexity of life to simplistic binary dichotomies. Thus, Hegnsvad suggests, Herzog focuses in both his feature films and his documentaries (accepting that even this labelling is far from established in Herzog’s work) on the dispossessed, the downtrodden, and the obsessed. “It is notable,” Hegnsvad observes, “that Herzog consistently engages with the people whom societal norms would dismiss as unsuccessful or deformed” (81). Within this category, Hegnsvad would include protagonists in feature films such as the vampire in Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), or the eponymous madman in Fitzcarraldo (1982) (both of course featuring Herzog’s favorite madman, Klaus Kinski, in the lead role), or in documentaries’ obsessive loners such as the engineer Graham Dorrington in The White Diamond (2004), or Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man (2005).

Another central feature of the author’s analysis of Herzog’s filmmaking style is the “ecstatic truth,” and in particular the use of landscape and space to achieve something of a transcendental moment. Herzog owes a certain debt to German Romanticism, as well as the films of Japanese master Yasujirō Ozu, Hegnsvad suggests. But instead of regarding the natural world as a place of redemption in the religious sense, it is figured as a heterotopic space, with the potential to function as a Deleuzian “any-space-whatever.” These images act as “in-between spaces within the narrative logic of a film,” Hegnsvad proposes, “where the image lingers and is caught up in itself rather than progressing to the next shot” (167). These moments of “any-space-whatever” correspond to the Herzogian principle of “ecstatic truth,” based upon the Greek sense of ekstasis where the individual steps away from their body for a time, to experience something ineffable, indescribable. In this spirit, Herzog shoots films about nomads and pilgrims, about obsessive outsiders and handicapped revolutionaries, tweeting Buddhist monks and crashed pilots pushing through the jungle, precisely because they defy the language of accountants and do not fit in to any definition of society. To these depictions he adds the dislocation of the wilderness, coupled with the inability of the individual to evade societal strictures. In The Wild Blue Yonder (2005), we see a “thoroughly Herzogian alien, unsuited (or ‘useless’) in every possible way for conditions on earth” (223), who is thus closely related to all of Herzog’s misfits

Citing French philosopher Jacques Rancière and his concept of “dissensus,” Hegnsvad thus proposes that Herzog’s films consistently seek to confront, to unsettle: “Herzog’s project is not to impose control and order, but to try to evoke the event qua event” (56).

Richly illustrated with film stills and photographs covering Herzog’s oeuvre over some seventy years of filmmaking, Hegnsvad’s work is a thoroughly entertaining and thought-provoking journey through the imagery of one of the most provocative filmmakers of the modern era. The book may disappoint some purists who are looking for a systematic account of Herzog’s career with an overarching examination of the director’s status as an auteur, but it should delight many more with its insights into the philosophy and “modus operandi” of this visionary chronicler of images. In a study that dwells lovingly on odd moments of filmmaking, Hegnsvad concludes with “one last oddment” (224), returning to the Rogue Film School and sharing with the director his favorite Herzog scene. To the director’s apparent delight (Herzog has already revealed that he sees the very act of filmmaking as ekstasis, stepping outside of his body), Hegnsvad cites the moment in Encounters at the End of the World (2007) when a solitary penguin leaves the colony and walks off into the icy wilderness, almost certainly to die. The penguin, too, stands as one of Herzog’s misfit heroes, stepping outside of society with no expectation of redemption, “existing in the spaces in-between in a state of constant becoming, like Herzog’s new images, joyfully hovering as potential” (224).

Hegnsvad’s work makes for a curiously fulfilling read (and here we should acknowledge the cogent translation of the original 2017 Danish edition by C. Claire Thomson)[1], one which defies conventional practice as a study of an author’s oeuvre perhaps, but which proves to be a fascinating, at times even exhilarating account of one of cinema’s mavericks—who is, in equal measure, one of cinema’s greats. The book contains a comprehensive filmography with synopses of all of Herzog’s works from his 1962 debut Herakles to Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds (2020). It also includes a list of his own appearance in others’ films, operatic works, and a selective bibliography of Herzog’s novels, poems, and essays. It is thoroughly recommended to the film studies academic and the passionate cineaste alike as a rewarding glimpse into the rationale behind Werner Herzog’s long and rich career.

Ian Roberts is Associate Professor in German Studies at the University of Warwick, UK. He teaches German language and the cultural history of Weimar and Nazi Germany. His published work includes German Expressionist Cinema: The World of Light and Shadow (Wallflower Press, 2008), and a recent article on war films in contemporary Danish cinema.

Werner Herzog: Ecstatic Truth and Other Useless Conquests

By Kristoffer Hegnsvad

Publisher: Reaktion Books

Hardcover / 288 pages / 2021

ISBN: 9781789144109

[1] Original title Werner Herzog: Ekstatik sandhed og andre ubrugelige erobringer

Published on April 18, 2022.