This is part of our special feature, Securitization of Identity.

Simone Perolari began the series Unwelcome in 2005 with a journalist friend. When he started the series in Lampedusa, the most famous European door, he was at the beginning of his photojournalist career. As soon as he arrived there, both costal guards and doctors of MSF told him that refugees would not arrive for at least two weeks due to the sea conditions. Only the night before leaving the island, after having almost resigned his work, a boat with 150 people reached the port. That landing truly marked the start of his experience as a photojournalist and also brought many emotions, sparked by seeing frightened people and noticing the incompetence of the young police officers of the Guardia di Finanza (thinking that maybe they were novice like him).

Between Lampedusa, Melilla, Ceuta, Oujda, Patrasso and Calais, Perolari traveled for six years. In each place, the story did not change. He always met poor people looking for a better life, a job to sustain themselves. Some of them were running away from war, others from hunger, but they were all escaping a country where a future would be impossible for them.

In Sicily, illegal immigrants from Maghrebi countries landed among annoyed tourists on vacation—in reality, they were capable of living together in the twenty square km of the island without ever meeting. Refugees were crammed into the first available reception center, a real prison island where human rights were optional.

In the African Spanish enclaves, Melilla and Ceuta, migrants traveled by foot through the wilderness and the desert. They remained hidden for years in the forests of Morocco, waiting to “get over the net.” As they were continuously hunted by soldiers and subjected to any kind of violence, many of them did not make it. Those who survived left for Mauritania to embark for the Canaries, but even there they found closed doors.

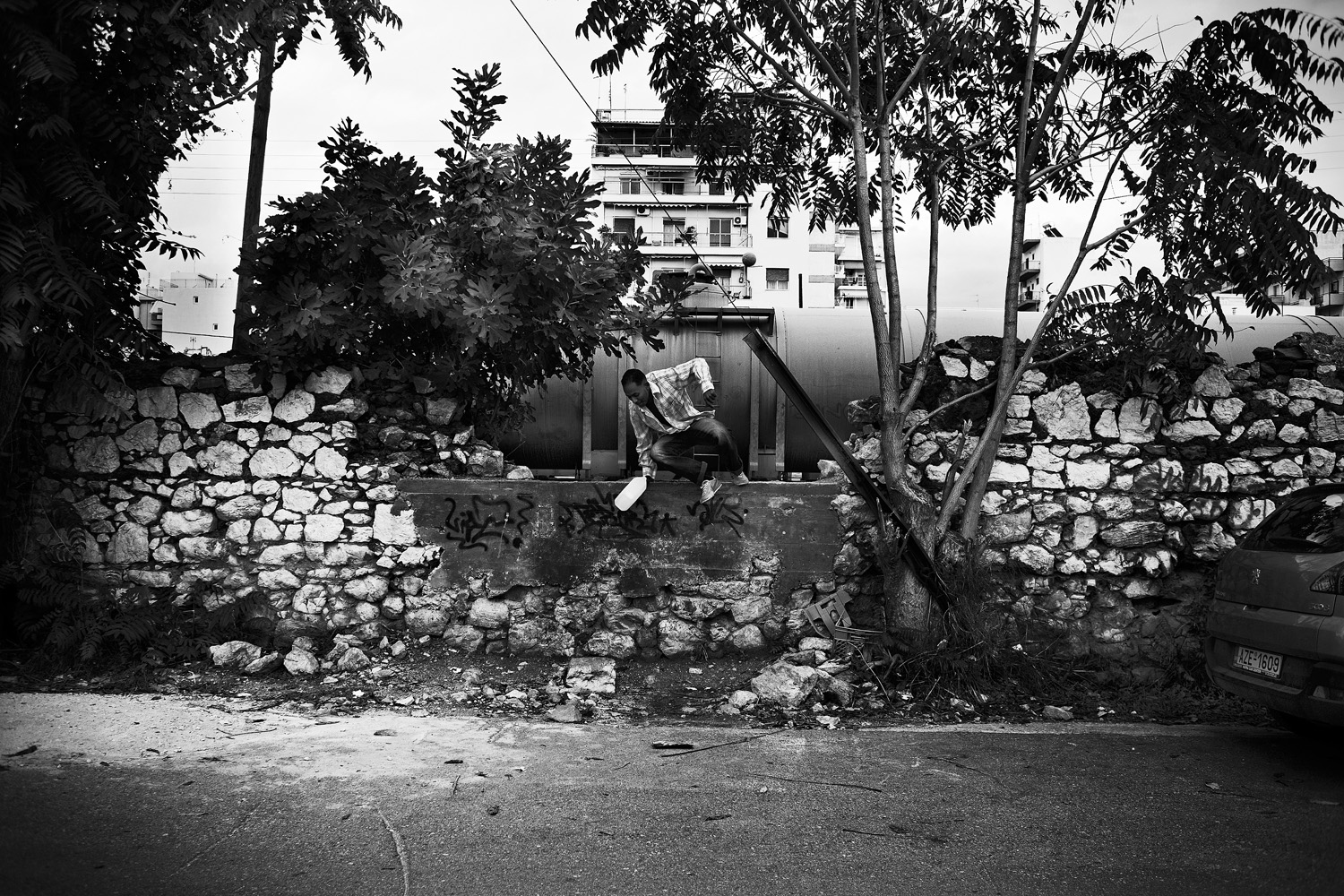

In Patras, 500 Afghans literally hid in the “forest,” as they called it—a large olive grove on the eastern outskirts of the city, hunted by the police, waiting to escape towards Italy, hiding under trucks. Every two or three days, the police arrived at dawn at the “clandestine camp,” a series of small camps made up of seven or eight boys, scattered around the olive grove. There, it destroyed the improvised shacks made with sheets and cardboard, arrested four or five Afghans fleeing the “forest” and left.

In Morocco, there was no passage because there were soldiers shooting, while Ceuta and Melilla were completely blocked by the Spanish police. From Libya to Italy too, it was impossible to pass. It became too dangerous because they threatened to sink any boat in sight. Today, refugees from all over the world are looking for a new way to enter Europe. The roads to reach the border between Turkey and Greece are the new Eldorado for people fleeing wars, famine, and poverty.

Even in Calais (already in Europe) the situation did not change. Every morning, the police raided the fields or the old industries where migrants lived momentarily, destroying their few belongings and even sending some of them back to other places. On a positive note, every week a professor went to Hotel Africa (the name of the place where people resided) to teach English to immigrants who did not speak it.

These are stories of migrants who dream of Europe, hoping to be welcomed, but who quickly understand that it will ultimately be an unwelcome.

Simone Perolari is an Italian full-time photojournalist who currently lives and works in Paris. Throughout his career, he has been collaborating with M le monde, New York Times, Der Spiegel, Howler magazine, CNN, Sportweek, Gazzetta dello sport, L’Equipe Magazine, Vanity Fair, Wired, Zeit, IOdonna and Corriere della sera. From 2005 until 2011 he documented the refugee crisis in Italy, Spain, Greece and France. He began a collaboration with Amnesty International, with which he published two documentary projects entitled “Lampedusa: Ingresso Vietato” (Lampedusa: Entry Prohibited) and “Invisibili” (Invisibles), a campaign raising awareness on the rights of undocumented minors in detention centers.

Follow Simone on Vimeo, Linkedin, Tumbrl, Instagram

Photos Copyright © Simone Perolari

Published on April 18, 2022.