Austria at the Crossroads of History: Choosing between Comfort and Conscience during the War in Ukraine

This is part of a series on the Ukraine Crisis.

Austro-Russian historic, political, economic, and cultural bonds

Complex cultural relationships between Russia and Austria span hundreds of years, years deeply rooted in rich imperial, political, and cultural interdependence. Unlike many other European countries, these two former imperial powers managed to not wage wars against each other until World War I, when Russia and Austria involuntarily crossed swords for the first time. Even though they fought on the opposite sides, they both experienced a similar end—they lost the war and underwent major transformations of their respective states, governments, and political systems.[1] With numerous tragedies befalling the two royal families, including suicides, assassinations, and executions, both monarchies ceased to exist. In the end, Russia’s monarchy was brutally replaced by the Soviet Communist regime, and Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved.[2]

Since then, according to the Russian ambassador to Austria Dmitriy Lyubinskiy, Russia and Austria have managed to maintain a very special bond and build “constructive relationships” that are mutually beneficial, pragmatic, and substantially dependent on the conscious personal contact and collaboration between the respective heads of the states.[3]Collaborative and mostly amicable relationships involve stable trade, numerous business and political visits, as well as vibrant cultural and scientific cooperation. Many of those bonds, however, have been highly controversial, questioning the ethics of the Austrian political elite and their dubious choice of profit versus patriotism. For example, in 2018, former Austrian foreign minister Karin Kneissl, who invited Russian President Vladimir Putin to her wedding and curtsied to him during the pompous ceremony in Austrian Gamlitz, was given expensive jewelry—and then a seat on the board of directors at the Russian state-controlled oil industry giant Rosneft.[4] A more recent corruption scandal, associated with Russian oligarchy and a honey-trap video that involved the Freedom Party of Austria (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, or FPÖ), pressured Austria’s Chancellor Sebastian Kurz to step down in 2021.[5]

Nonetheless, regardless of the scandals and controversies, various bonds remain strong. So is Austrian-Russian interdependency—and in some instances, Austrian dependency on Russia. According to Elisabeth Christen, Senior Economist at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research (Österreichisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, WIFO), about 80 percent of Austria’s natural gas is imported from Russia.[6]What it means is that the immediate embargo on Russian gas would certainly hurt Austria more than it would hurt Russia, so the Austrian government declared it will continue to import Russian gas and oil.

Politics and economics are not the only foci of Austrian-Russian relationships. Cultural exchange and collaboration have also been at the core of convenient interdependence. For example, every February, the Viennese majestic imperial residence Hofburg (Figure 1) opens its doors for the guests of the annual Russian Ball. Similarly, young and beautiful debutantes of 16-23, in stunning white gowns and tiaras—daughters of Kremlin’s ultra-rich elite—regularly debut at the annual Viennese Ball in Moscow, held in the largest ballroom Gostiny Dvor.[7]Whether Moscow or Vienna, those balls with an air of imperialist nostalgia, are a major stepping-stone to life at the top of Austrian and Russian societies, respectively.

Figure 1: Hofburg Imperial Palace, Heldenplatz, Vienna, Austria

Opera, ballet, and theater collaborations are equally impressive, revealing just how deep and multifaceted Austrian-Russian relations are. Established in 2019, Russian-Austrian public forum Sochi Dialogue in collaboration with the Austrian Cultural Forum Moscow, hosted a series of discussions on cross-cultural theater dialogues between Austria and Russia.[8]Both platforms provide another typical example of the type of joint work, in which Austria and Russia have been involved for quite some time, prior to February 24, 2022, the day when Russia invaded Ukraine—its former Soviet br/other, and—paradoxically—its former brother-in-arms in the World War II.

Russian soldier-liberator…. turned oppressor

For millions of former Soviet citizens, the sacrality of memory of World War II is central to their own cultural identity and understanding of Selves as the morally superior Soviet superpower that liberated Europe from the Nazi yoke. For a great variety of reasons, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, Sovietness became understood and used interchangeably with Russianness, nationally and internationally. Decades after World War II, the pompous Soviet materiality continued to remind the Austrians about the Soviet/Russian victimhood, sacrifice, and heroism.

Figure 2: Heroes’ Memorial to the Red Army Vienna, Austria, since February 2022-present.

World War II and the preservation of the image of Russian soldiers as heroes and liberators of Europe from the Nazi plague, used to be a sphere where Russia and Austria seemed to have a mutual understanding. Maintaining that same level of understanding became much harder once the first harbingers of today’s blue-and-yellow colored Vienna appeared in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Then, the memorial to Soviet soldiers in Vienna was painted over in the colors of the Ukrainian flag.[9] Russia called for vandals to be found and punished. The vandalism happened again in 2018 and again in 2019, these times the paint was black.[10]Lyubinskiy mentioned that the Austrian side always promptly reacted to Russia’s indignation and made sure the perpetrators were found and the monuments were cleaned.

The new war, however, has become an ambivalent subject for both sides, something that can be referred to as a “deal-breaker” of the once strong relationships between Russia and Austria. This time, the famous monument turned blue-and-yellow again (Figure 2). Furthermore, in early April, a major demonstration to honor the lost lives of Ukrainian children happened at the memorial, creating the so-called “mobile monument to the youngest victims of the war,” with activists placing prams, teddy bears, bicycles, flowers, and candles to commemorate the dead children.[11]

Russia, which seemed interested in a cross-cultural dialogue and collaboration with once notoriously neutral Vienna, became increasingly critical of the country’s stance on the armed conflict in Ukraine. Importantly, in December 2021 Austria’s Chancellor Karl Nehammer referred to Austria as a “bridge-builder,” taking a “conciliatory approach towards Russia.”[12]And indeed, unlike Germany, or the USA, Austria denied Ukrainian President and persuasive speaker Volodymyr Zelensky permission to address the Austrian parliament, on the grounds of Austrian political neutrality. In early March 2022, as the situation in Ukraine continued to escalate, Austria once again expressed its resolution to adhere to its neutral status which, however, did not mean withholding expression of solidarity when there is “an international need.”[13]

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs immediately retorted, calling Austrian remarks “one-sided and outrageous,” and condemning the Austrian Chancellor for the use of anti-Russian rhetoric, referring to Austria as only seemingly neutral.[14]Especially telling in the Ministry’s statement is the connection of Austria’s achieving its independence after World War II with the “irrevocable losses” the USSR suffered during that war. The transition smoothly and strategically ties together the freeing of Austria’s territory from the Nazis to 26 million lost Soviet lives, delivering a bitter reproach (and conveniently neglecting the fact that 8 million of those lives were Ukrainian). Russia pointed out that Austrian neutrality is “eroding.” The Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded via Twitter in German and Russian that “Austria is a neutral state in a military sense. But we are never politically neutral when it comes to respect for international law.”[15]

At the end of 2021, Lyublinkiy wondered whether somewhat “privileged” relationships between Austria and Russia leave a “window of opportunity” open for both sides; it recently became clear that that “window,” if it ever existed, is being shut by Austria.[16] And indeed, according to Reliefweb, an online service provided by The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Austria has already provided Ukraine with more than €17.5 million from the Foreign Disaster Fund.[17]Austria also supplied 10,000 helmets and over 9,100 protective vests for civilian use.[18]Numerous demonstrations and solidarity marches, against the war in Ukraine, took place all over the country, with the biggest of them at the very heart of Vienna, Heldenplatz, in front of the Hofburg Imperial Palace, with thousands of Austrians marching and demonstrating all over the city.[19]

Figure 3: Solidarity Marches, Heldenplatz, Vienna, Austria.

Following recent reports of Russian atrocities and war crimes committed against Ukrainian civilians in the town of Bucha, a suburb of Kyiv, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer visited President Volodymyr Zelenskiy.[20]Nehammer’s aim is to continue providing Ukraine with humanitarian and political support, yet Ukraine is hoping for a stronger engagement of Austria in its fight against Russia. Although originally critical of other EU nations for expelling Russian diplomats, Austria’s Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenbers/the Austrian Foreign Ministry declared four Russian diplomats as “personae non gratae.”[21]Although Austria still aims for perpetual neutrality regarding military activities, it declared that it would not stay neutral when it comes to human rights. Nehammer’s visit to Bucha might be that tipping point, because, with all due respect to neutrality and century-long Austro-Russian amicable relations, Austria cannot afford to be on the wrong side of history again. Never again.[22]

Between Scylla & Charybdis: Never Again?

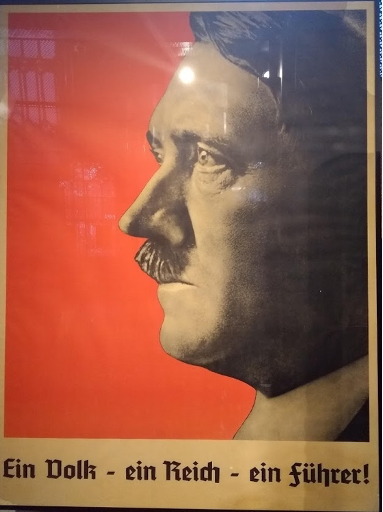

Never again has a very special meaning to Austria, because of its problematic past, and the infamous Austrian Anshluss/Connection/Unification with Hitler’s Germany, when an alarming number of 99 percent of the Austrians said “yes” to the reunification of Austria with the German Reich, under the leadership of its ambitious Führer, Adolf Hitler. A powerful combination of Hilter’s insatiable ambitions of world dominance, with a smart propaganda in both Germany and Austria certainly played their part. Some of the propaganda visuality is still on display at the Viennese Heeregeschichtliches Museum HGM/Museum of Military History. One of the prominent propaganda posters reads: Ein Volk, ein Land, ein Führer/One people, one country, one leader (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Propaganda Poster Ein Volk, ein Land, ein Führer/One people, one country, one leader Museum of Military History, Vienna, Austria.

Another poster focuses on Hitlerjugend/Hitler Youth, and reads Führer, wir gehören dir/Führer, we belong to you, and also elaborates: ‘Die Zukunft kann uns nichts anderes bringen als den Sieg. Und wenn uns die Welt nach den Gründen fragt, so sagen wir: Weil uns der Herrgott unsem Führer gab/The future can bring us nothing but victory. And when the world asks us why, we respond: Because the Lord God gave us our Führer.

The cult of Hitler’s personality, the pressure of the German occupation of Austria, and the power of the propaganda all contributed to the infamous Anschluss/Unification.

Over decades, Austria attempted to cleanse (and often erase) its Nazi-related past. Art and architecture followed suit, to clearly communicate Austrian standing. The Monument Against War and Fascism (see Figure 5), located near Staatsoper/Vienna State Opera and next to Albertina art gallery, is a vivid reminder of Austria’s adherence to #NeverAgain positionality, preserving the memory of the Holocaust and ensuring that nothing as terrible will ever happen again.

The monument consists of several elements, starting with Tor der Gewalt/Gates of violence or gates of war. The piece of granite rock in this element is made from the granite of the Mauthausen quarry, located near the Mauthausen concentration camp. Two parts of the Gates of violence represent victims of persecution and repressions, and the other one stands to remind the viewer about the lives lost in war actions. Stepping out of the gates we see a statue of the group—an old Jew wrapped in barbed wire, depicting the humiliation, and suffering the Jews experienced in the antebellum years and during the war. The monument serves as a palpable witness of Austria’s anti-fascist standing.

Figure 5: The Monument against War and Fascism, Vienna, Austria.

Already after Putin’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, his government was called fascist, and he started being compared to Hitler. In 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, the metaphor was resurrected. Importantly, Putin’s Russia called the annexation Reunification and proudly celebrated the outcome of the referendum, held in the Russian-occupied Crimea, with 98 percent of citizens saying “yes” to the Reunification. Same script, different cast. With the current war in Ukraine, the comparison of Hitler and Putin takes a linguistically and visually fused form of Putler—not only in Europe but already worldwide.[23]

With many comparing Putin to Hitler, it is not surprising that Austria attempts to find itself dissociated with Russia, but only as long as it does not hurt its national interests. Maslow’s pyramid of Austrian needs, a la carte, a paradoxical situation which—sadly—considerably clouds Austrian vision and helps Putin’s Russia. History taught us just how, once the conceptual move from Austria as a victim of Nazism to Austria as involved in the Third Reich’s crimes happened, the price for staying supportive of the regime that no longer adheres to Geneva Law became too high.[24] Austria cannot afford to pay it again. Yet, it keeps rejecting immediate economic, political, and cultural independence from Russia, or more active support of Ukraine. While Austria keeps waltzing with the insatiable Russian bear, the latter commits unforgettable and unforgivable war crimes and crimes against humanity on European soil, making Austrian inactivity and neutrality appear synonymous with complicity.

Austria and Russian arsonists

With the current war in Ukraine, Austria finds itself at the crossroad of history in the making, having to choose between economic and political comfort and its political conscience. Austria clearly opposes the war and communicates it through numerous rallies, demonstrations, marches of solidarity, and public addresses. Cultural and educational institutions all over the country are vivid examples of Austrian pro-Ukrainian allegiance (see Figures 6-9). Major museums, theaters, and universities all communicate their pro-Ukrainian statements, which read “Stand with Ukraine,” or “Stop War in Ukraine.” University of Vienna (Figure 7) added the Ukrainian flag next to the Austrian and the EU ones.

Figure 6: Burgtheater, “Stand with Ukraine,” Vienna, Austria

Figure 7: University of Vienna Flags, Vienna, Austria

Figure 8: Secession, Association of Visual Artists, “Stop War in Ukraine,” Vienna, Austria

Figure 9: Opera, Vienna, Austria

World-famous Viennese opera (Figure 9) turns blue-and-yellow every evening, with neon posters reading “Peace. Stop That War.” Inside the Opera—unlike the majority of other EU countries who banned many Russian artists—Austria carries on with hosting breathtaking Russian performances, rejecting the so-called “cancel culture,” and re-emphasizing—once again —its neutrality. And hoping that the stunning surface-level blue-and-yellow embellishment of the city (and the country) will suffice. Importantly, the Opera house is famous for its monstrous energy consumption, so, it’s not just the beautiful ballerinas and mezzo-sopranos that make Russian presence so undeniable, so scaringly natural. That undeniable Russian presence makes the slogan “Stop That War” seem like an oxymoron, or an aesthetically pleasing piece of empty rhetoric at best, while the war atrocities continue.

In the last couple of weeks, thousands of civilians died in Ukraine. Many, too many were children. Thousands lost their homes and fled the country. During that short period of time, millions of Ukrainians have reinvigorated the European ideals of democracy and freedom, or resistance against autocracy. Ukraine is paying an extremely high price for its choice—higher, much higher than the price of Russian gas and oil. Under such circumstances, Austrian neutrality, and its reluctance to do—and to be—more, is playing into Putin’s hands. Metaphorically speaking, Austria currently resembles Max Frisch’s satirically tragic figure of proper and non-confrontational Biedermann, from Biedermann und die Brandstifter/The Arsonists, whose positionality towards the criminals eventually results in a major tragedy. The play is often seen as a metaphor for fascism and Nazism, with a strong element of critique of the insufficient social and moral standing of such Biedermanns who involuntarily become accomplices of amoral and merciless arsonists.

While Russian military arsonists are firing at countless civilians in Ukraine, Austria has a chance to rewrite—and relive—Frisch’s play.

Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager is Associate Professor at Colorado State University, specializing in Critical Cultural Communication & International Studies. She is Director/Leader of Education Abroad programs in Italy, and Associate Program Director of ACT International Human Rights Film Festival.

Evgeniya Pyatovskaya is a PhD Candidate at University of South Florida, specializing in Intercultural Dialogue, Organizational Communication & Transnational Feminism. She is a former Fulbright Scholar from Colorado State University, and an Atlas Corps Fellow, New York.

References

[1] Ulrike Harmat, “The German-Austrians at the End of World War I,” Les Cahiers Irice 13, no. 1 (2015): p. 105, https://doi.org/10.3917/lci.013.0105.

[2]Patrick J. Kiger, “How World War I Fueled the Russian Revolution,” History.com (A&E Television Networks, April 28, 2021), https://www.history.com/news/world-war-i-russian-revolution; Dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire,” Czech Center Museum Houston https://www.czechcenter.org/blog/2020/12/14/dissolution-of-the-austro-hungarian-empire.

[3]“Интервью Посла России … – Austria.mid.ru,” accessed April 12, 2022, https://austria.mid.ru/ru/press-centre/news/intervyu_posla_rossii_v_avstrii_dmitriya_lyubinskogo_parlamentskoy_gazete/.

[4] “Austrian Ex-Foreign Minister in Putin Wedding Row Set for Job in Russia,” BBC News (BBC, March 4, 2021), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56280898.

[5] Bethany Bell, “Austria Scandal: Mystery of the Honey-Trap Video,” BBC News (BBC, May 23, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48378320.

[6] Kate Abnett, “No EU Countries Have Signalled Gas Supply Emergencies, European Commission Says,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, March 31, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/no-eu-countries-have-signalled-gas-supply-emergencies-european-commission-says-2022-03-31/.

[7] Lauren Lewis , “Daughters of Kremlin’s Ultra-Rich Elite Debut at 18th Vienna Ball in Moscow,” Daily Mail Online (Associated Newspapers, May 31, 2021), https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9636343/Daughters-Kremlins-ultra-rich-elite-debut-18th-Vienna-Ball-Moscow.html.

[8] “Official Website. Sochi Dialogue.,” Sochi Dialogue, accessed April 12, 2022, https://sochidialogue-en.com/.

[9] “Russia Complains about Statue Vandalism in Austria,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty (Russia Complains About Statue Vandalism In Austria, May 8, 2014), https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-vienna-statue-vandalized/25378200.html.

[10] “Russian Embassy in Austria Demands Vandals of Vienna’s Soviet War Memorial Be Punished,” Tass.com, January 10, 2018, https://tass.com/society/984476?utm_source=google.com&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=google.com&utm_referrer=google.com; “Vandals Drown Soviet Liberator Monument in Vienna in Paint,” Tass.com, April 25, 2019, https://tass.com/world/1055621.

[11] Gerald John, “Vor Wiens ‘Russendenkmal’ Wurde Der Toten Kinder Gedacht,” Vor Wiens “Russendenkmal” wurde der toten Kinder gedacht, April 2, 2022, https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000134631340/vor-dem-russendenkmal-wurde-der-toten-kinder-gedacht?ref=article.

[12] Oliver Noyan, “Austria Wants to Become ‘Bridge Builder’ in Ukraine Conflict,” www.euractiv.com (EURACTIV, December 14, 2021), https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/austria-wants-to-become-bridge-builder-in-ukraine-conflict/.

[13] Elizabeth Schumacher, “Germany’s Scholz Hosts Austria’s Nehammer to Talk Ukraine,” DW.COM, March 31, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-scholz-hosts-austrias-nehammer-to-talk-ukraine-russia/a-61318176.

[14] “Заявление МИД России в … – Mid.ru,” Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации, March 5, 2022, https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/themes/id/1803110/.

[15] Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Twitter, March 5, 2022), https://twitter.com/MFA_Austria/status/1500181339907231756?s=20&t=ALzX7_wBJIL1yRzA98YZAA.

[16] Дмитрий Любинский. “Из прошлого и настоящего отношений России и Австрии: солидный фундамент и окно возможностей.” Дипломатическая служба и практика.4, no. 4 (2021) 62-69.

[17] “Austria Supports Ukraine with Additional 15 Million Euros in Humanitarian Aid from the Foreign Disaster Fund – Ukraine,” ReliefWeb, March 7, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/austria-supports-ukraine-additional-15-million-euros-humanitarian-aid-foreign.

[18] Nikolaus J. Kurmayer, “Austrian Chancellor to Travel to Kyiv,” www.euractiv.com (EURACTIV, April 6, 2022), https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/austrian-chancellor-to-travel-to-kyiv/.

[19] “Wien: 2.200 Menschen Demonstrierten Gegen Ukraine-Krieg,” vienna.at, March 21, 2022, https://www.vienna.at/wien-2-200-menschen-demonstrierten-gegen-ukraine-krieg/7337167.

[20] Max Bearak and Louisa Loveluck, “In Bucha, the Scope of Russian Barbarity Is Coming into Focus,” The Washington Post (WP Company, April 7, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/06/bucha-barbarism-atrocities-russian-soldiers/; “Zelenskiy / Official,” Telegram, accessed April 12, 2022, https://t.me/V_Zelenskiy_official/1180; Ukrinform, “Zelensky Thanks Austrian Chancellor for Supporting Ukraine,” Ukrinform (Укринформ, April 9, 2022), https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/3453133-zelensky-thanks-austrian-chancellor-for-supporting-ukraine.html.

[21] “Austria Kicks out Four Russian Diplomats,” Tass.com, April 7, 2022, https://tass.com/politics/1433807.

[22] Hayley Maguire, “Austria’s Nehammer to Visit Zelensky in Ukraine,” The Local Austria (The Local, April 5, 2022), https://www.thelocal.at/20220405/austrias-nehammer-to-visit-zelensky-in-ukraine/.

[23] Katarzyna Jamroz, “[Wideo] Vladolf Putler? Austriacy Kpią z Prezydenta Rosji,” Głos24, March 8, 2022, https://glos24.pl/wideo-vladolf-putler-austriacy-kpia-z-prezydenta-rosji; Charlene Rodrigues, “In Pictures: Protesters Worldwide Rally against Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” The Independent (Independent Digital News and Media, February 24, 2022), https://www.independent.co.uk/world/russia-invasion-ukraine-world-reaction-b2022595.html; Terrence McCoy, “Here’s ‘Putler:’ the Mash-up Image of Putin and Hitler Sweeping Ukraine,” The Washington Post (WP Company, October 26, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/04/23/heres-putler-the-mash-up-image-of-putin-and-hitler-sweeping-ukraine/; Natalia Knoblock and Natalia Beliaeva, “Blended Names in the Discussions of the Ukrainian Crisis,” in Language of Conflict: Discourses of the Ukrainian Crisis (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022).

[24] Michael Z. Wise, “Austria Admits Role in Holocaust,” The Washington Post (WP Company, July 9, 1991), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1991/07/09/austria-admits-role-in-holocaust/a7485c1c-3a82-4558-852e-b222983a386a/; “United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect,” United Nations (United Nations), accessed April 12, 2022, https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/war-crimes.shtml.

Published on April 13, 2022.