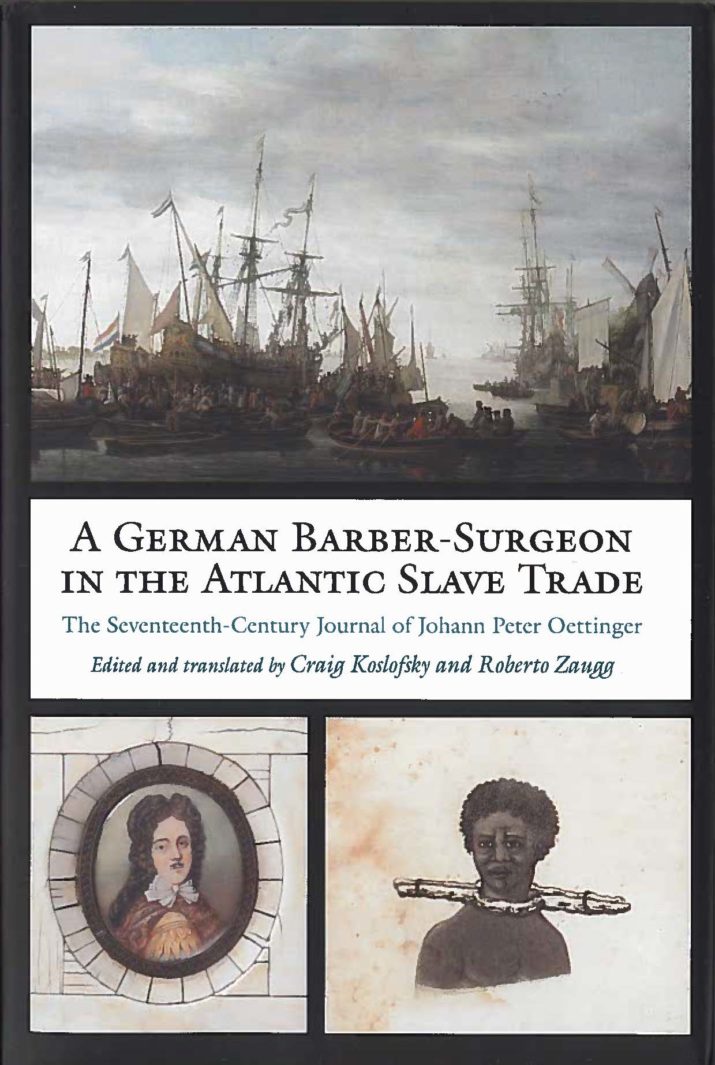

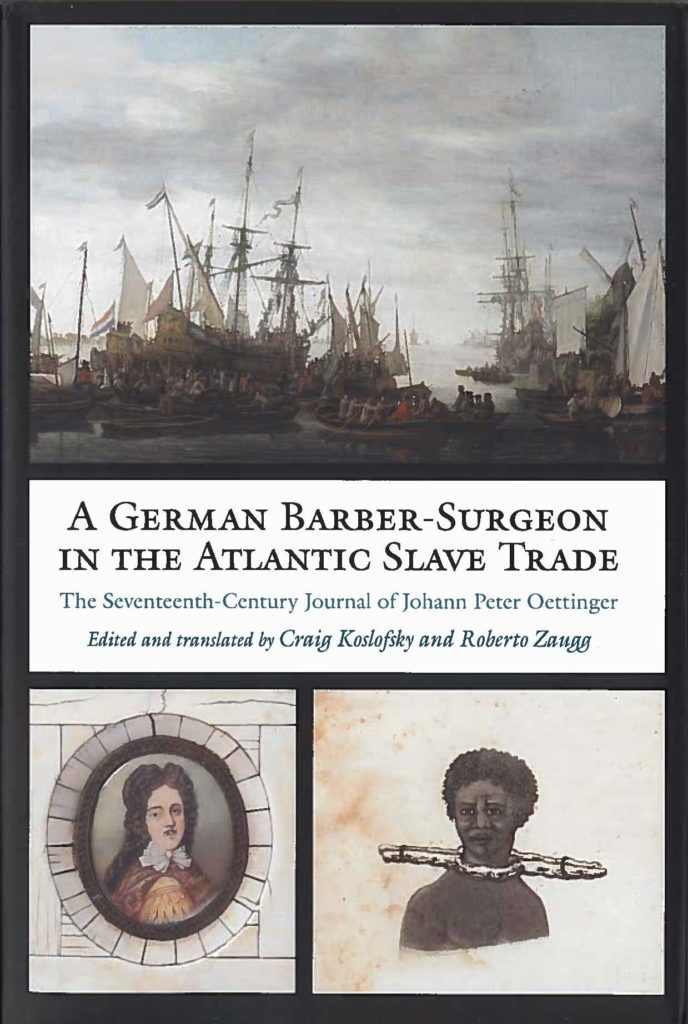

A German Barber-Surgeon in the Atlantic Slave Trade: The Seventeenth-Century Journal of Peter Oettinger edited and translated by Craig Koslofsky and Roberto Zaugg

On June 5, 1688, twenty-three year-old Johann Peter Oettinger boarded the Dutch West India Company (WIC) ship Juffrouw Alida at the Dutch island of Texel. As a young German journeyman from western Franconia who worked to obtain experience as barber-surgeon in training, he was about to embark on his first of several transatlantic voyages.[1]During his employment on the Juffrouw Alida, from 1688 until 1690, he would help transport over four hundred enslaved men, women, and children from the Dutch island of Curaçao to other parts of the Caribbean. Intended as a record of his employment, Oettinger wrote about his experiences on board the ship in a journal, including serving as midwife to deliver the three children of women held captive on the ship. Perhaps because he kept the journal for professional purposes, his personal opinions on such human trafficking voyages remained absent from his descriptions. In 1692, two years after returning to the Dutch Republic, he would board the Brandenburg African-American Company (BAAC) ship the Friedrich Wilhelm, Kürfurst von Brandenburg for another slaving voyage, seemingly undeterred by what he had lived on the Juffrouw Alida.

Historians have known about Oettinger’s 1681-1696 journal through the volume Unter kurbrandenburgischer Flagge, a significantly modified version of the original manuscript that was published in 1885/1886 by his descendant Paul Oettinger. Yet, it was not until recently that both Craig Koslofsky and Roberto Zaugg independently discovered a more faithful 1779 copy of the original journal by Johann Peter’s grandson, George Anton, at a Berlin archive, which they translated into English and published here. By adding to it an extensive, 83-page long introduction, they provided context to the journal and detailed information about Oettinger and the world in which he lived.

Oettinger divided his journal along his various “travels.” He had begun writing soon after his apprenticeship with a master surgeon in Schwäbisch Hall had completed and he first embarked upon his travels throughout the Holy Roman Empire and the Dutch Republic in search of work. The book starts with a detailed account of his 1683-1687 journey to Düsseldorf and Amsterdam, where, after a short stay, he was recruited by the WIC to serve on the Juffrouw Alida. He goes on to describe his position on the Friedrich Wilhelm and the voyage back to Europe when that ship was captured by the French. After being held captive for several weeks on board a French ship, Oettinger was freed in Brest after he claimed he was Dutch rather than German. He then embarked on a months-long trek, much of it by foot, back to Emden. The last three years of his journal detail his travels in, among other places, West Friesland, as well as his final return home where he would marry and begin his life as a master barber-surgeon.

While Oettinger’s journal also detailed his ventures in Europe, it is the descriptions of the Dutch and Bavarian slavers that are particularly valuable to historians. Indeed, reconstructing the experiences of people who made these voyages has proven incredibly challenging, in large part because few records have documented what happened on board slave ships. Although scholars, including Robert Harms, Sowande’ Mustakeem, Stephanie Smallwood, Marcus Rediker, Sean M. Kelley, Leo Balai, and Ad Tramper, have begun to reconstruct such eighteenth-century voyages,[2] few have covered the seventeenth-century slave trade, and even less attention has been paid to German involvement. Frank Dragtenstein’s Van Elmina naar Paramaribo: De Slavenhaler provides a rare exception.[3] Therefore, A German Barber-Surgeon in the Atlantic Slave Trade will undoubtedly help advance scholarly research of the seventeenth-century Dutch and German trade.

Johann Peter Oettinger provided especially substantial and descriptive entries of the Friedrich Wilhelm’s voyage. That ship traveled from Emden to the Gold Coast, where it anchored at the Brandenburger Company castle Grossfriedrichsburg for two months. From there, it proceeded to Hueda, Cape Lopez—in present-day Gabon—Sâo Tomé, and eventually St. Thomas, before travelling back to Europe. Most days, Oettinger recorded the ship’s location, the weather, and events of note. Writing at Castle Grossfriedrichsburg, Oettinger focused especially on the patients he treated there, including “several patients with gonorrhea, cankers, sores, and suchlike” (32-33). In Hueda, he recorded his visit to the king’s castle in the capital city Savi. Among other events there, he detailed how he selected 80 to 100 men, women, and children for purchase, before a company official would burn the letters CABS (Churfürstliche Africanische Brandenburgische Compagnie) on their right shoulder and take them to the ship.

Oettinger’s journal also gives invaluable insights into the experiences of the people these ships forcefully transported. For instance, he noted that men, women, and children taken in Curaçao on the Juffrouw Alida were considered Mairon (also called manqueron, macqueron, or makeron): enslaved people who could not be sold in the more profitable Spanish slave trade due to age or illnesses. During their three-month Caribbean journey, eighty-three of these captives would die and three women would give birth. Later on, when writing about the transatlantic passage on board the Friedrich Wilhelm, Oettinger described how the enslaved engaged in acts of resistance, for example when a woman killed and threw her young child overboard, and when a group of bombas—enslaved men tasked with surveillance of other captives—used their relative freedom of mobility in an unsuccessful attempt to take over the ship. Oettinger avoids deep commentaries on these events, which he simply describes without betraying much of his personal emotions or thoughts. This is one of many limits to these types of travelogues for those attempting to read motivations or mentalities into historical actors, though it does not negate the fact that this is still an immensely rare and valuable historical source.

Doubtlessly, Oettinger’s narrative provides crucial information about the day-to-day operations of seventeenth-century slavers. As the volume’s editors point out, however, the reader should remain cautious. For one, Oettinger did not always use his own words when describing places or events. When he described Hueda, for instance, he appears to have borrowed from a previous description of the Gold Coast by Wilhelm Johann Müller, which had been published in the 1670s (lxxii, 78-80). When discussing the three women who gave birth on the WIC ship Juffrouw Alida, he repeated stereotypes of African women common to European travel literature: “The mother lies in no child-bed; instead she walks straight away [after giving birth] like a cat does with its young…They bind the [newborn] child on their back with an old linen cloth, throw their breast to him over the shoulder, and let them suckle”(13).[4] Perhaps Oettinger relied on such racist tropes to help distance himself from the people he helped enslave. In spite of this necessity for the reader to remain aware of such borrowing, the journal entries do provide a rare look into Oettinger’s world.

Koslofsky and Zaugg did a wonderful job translating and editing the narrative. In particular, their detailed introduction contextualizes the document and Oettinger’s life perfectly. In addition to the appendix that includes documents for comparison, an annotated guide to sources and an extensive bibliography prove incredible resources for researchers. In all, this publication will give many scholars access to a rare German-language journal that gives an impression of a seventeenth-century barber-surgeon’s life and provides an important account of the WIC and BAAC slave trade from someone who witnessed it first-hand. As such, it will serve as an important text for many scholars, but especially for those who study Dutch and German involvement in the seventeenth-century transatlantic slave trade.

Andrea C. Mosterman is an associate professor in Atlantic history and Joseph Tregle Professor in Early American History at the University of New Orleans. In her research, she explores the multi-faceted dimensions of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade in early America and the Dutch Atlantic World. Her recently published book Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York provides a spatial analysis of enslavement in New York’s Dutch communities. She is currently researching the 1663/1664 voyage of the Dutch slaver Gideon to New Amsterdam/New York.

A German Barber-Surgeon in the Atlantic Slave Trade: The Seventeenth-Century Journal of Peter Oettinger

Edited and translated by Craig Koslofsky and Roberto Zaugg

Publisher: University of Virginia Press

Hardcover / 222 pages / 2020

ISBN: 978-0813944456

References

[1] Slavers usually had barber-surgeons on board to provide medical care for its crew and the captives it would transport.

[2] Leo Balai, Het Slavenschip Leusden: Over de slaventochten en de ondergang van de Leusden, de leefomstandigheden aan boord van slavenschepen en het einde van het slavenhandelsmonopolie van de WIC, 1720-1738 (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2011); Robert Harms, The Diligent: A Voyage Through the Worlds of the Slave Trade (New York: Basic Books, 2002); Sean M. Kelley, The Voyage of the Slave Ship Hare: A Journey into Captivity from Sierra Leone to South Carolina (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Sowande’ Mustakeem, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2016); Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (New York: Penguin Books, 2007); Stephanie E. Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007); Ad Tramper, Een Zeeuws slavenschip: Na de kust van Guiné om slaven, de wind oost (Vlissingen: Uitgeverij Den Boer|De Ruiter, 2014).

[3] Frank Dragtenstein, Van Elmina naar Paramaribo: De Slavenhaler (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2017).

[4] Jennifer L. Morgan, “‘Some could suckle over their shoulder’: Male Travelers, Female Bodies, and the Gendering of Racial Ideology, 1500-1770,” William and Mary Quarterly 3d. ser., 54, no.1 (1997): 167-92.

Published on April 5, 2022