Translated from the Turkish by Nermin Menemencioğlu.

diary ’50–’52

Today, Bedri took me and Meral to Lambo’s, a small, pleasant tavern near the fish market. All the poets, painters, and jour-nalists go there. Bedri had a poem published in Varlık, so he invited us to celebrate, and we drank wine. Without their par-ents or my parents knowing, of course. If they heard about it, all hell would break loose.

***

My mother was on a rampage again today. My father’s been fired, she carried on endlessly about it. “He crosses swords with the bosses, talks back to them, as if there’s some mansion waiting for us on one of the islands, why make a fuss about law and justice, you’d be better off if you’d just keep your big mouth shut.” So I asked, “What do you expect him to do, Mother, let them walk all over him because they’re the bosses?”

She scolded me, “You keep out of this. You’re two of a kind anyway, nothing but hot air for brains.” If my father had heard her, he’d have thrown the book at her, but never mind! Meral and I skipped the last lecture and went to Lambo’s instead. We met a poet and a short-story writer. They were very nice. I’d like to read my poems to one of them, but I’m too shy. Meral asked me why I don’t show my poems to Bedri. She doesn’t know her brother’s been coming on to me for some time now. I don’t much care for him. Today I told Monsieur Lambo that I’d like to have someone read my poems, and he introduced me right away to a man drinking at the bar. I hadn’t realized the man was Him. My heart leapt into my throat, I pretended I didn’t have the poems with me. We’re going to meet tomorrow, at a place called Çardaş in Tünel, and he’ll read my poems. That is, if I don’t choke on my excitement before then.

Çardaş is a long, dark corridor of a place. A vast, frighten-ing darkness. I couldn’t see him at first. A white figure rose and waved from somewhere at the far end. We sat down fac-ing each other and began a halting conversation. He seemed bored or embarassed, and his demeanor infected me, too. I wished a thousand times over that I hadn’t come. Suddenly he said, “Well then, chief, let’s hear what you’ve got—go on, read!” His rudeness upset me, and so I struggled through one of my poems, the one that ends with these rather beautiful lines: “Who are they that drive us underground / while the skies are deepest blue, brothers, and our faces so pale.” “Are you a worker somewhere?” he asked, dead serious. I coudn’t tell if he was making fun of me. I told him, “No, but I have relatives who are.” He was silent. Then I read from my “Sonnet of Fallen Girls”: “Shall it be always with tears in their eyes that our girls are not sent off to war?” He scratched his nose. “So you want to go to war?” was his response this time. I explained that “war” was used here in a very broad sense; this poem expressed the thought that so long as women were kept from engaging in battles of any sort, they’d end up as an “army of fallen girls.” It was odd that he hadn’t gotten the point. To finish, I read my poem “Blood,” about the day I got my first period, meant to express the panic that seized me at the time:

Is this the heel of mighty Achilles

pierced in my very bed,

Or some great gaping wound

where eagles have collided in the sky?

Ceaseless, the blood

the pain that settles on her lungs

drowning eyes, the sea, wrists

drowning the sea shackled in chains

drowning drowning ceaselessly.

“What blood is this, I’m not quite with you?” he asked, narrowing his eyes. I’d made that part sound abstract so that it would be difficult to understand. I couldn’t tell him the truth, of course, so I said, “I was trying to symbolize the dread of war.” “Well done, that’s a fine job you’ve done, but you’re a lit-tle too young to be a poetess. Let these sit for a few months, then read them over again. I’ll bring you some books tomor-row, to Lambo’s, read those, too.” He was being polite, but he obviously hadn’t liked my poems. He was probably laughing to himself the whole time. “Keep on writing, write and then write some more, then put it aside, but never stop writing.” Now I was bereft of any hope for my poetry, my sole refuge, my lone consolation. What’s the point of living after this? I might as well just die. I went to Lambo’s and picked up the books. He wasn’t there. They’re all books I’ve already read! I’m so dreadfully unhappy!

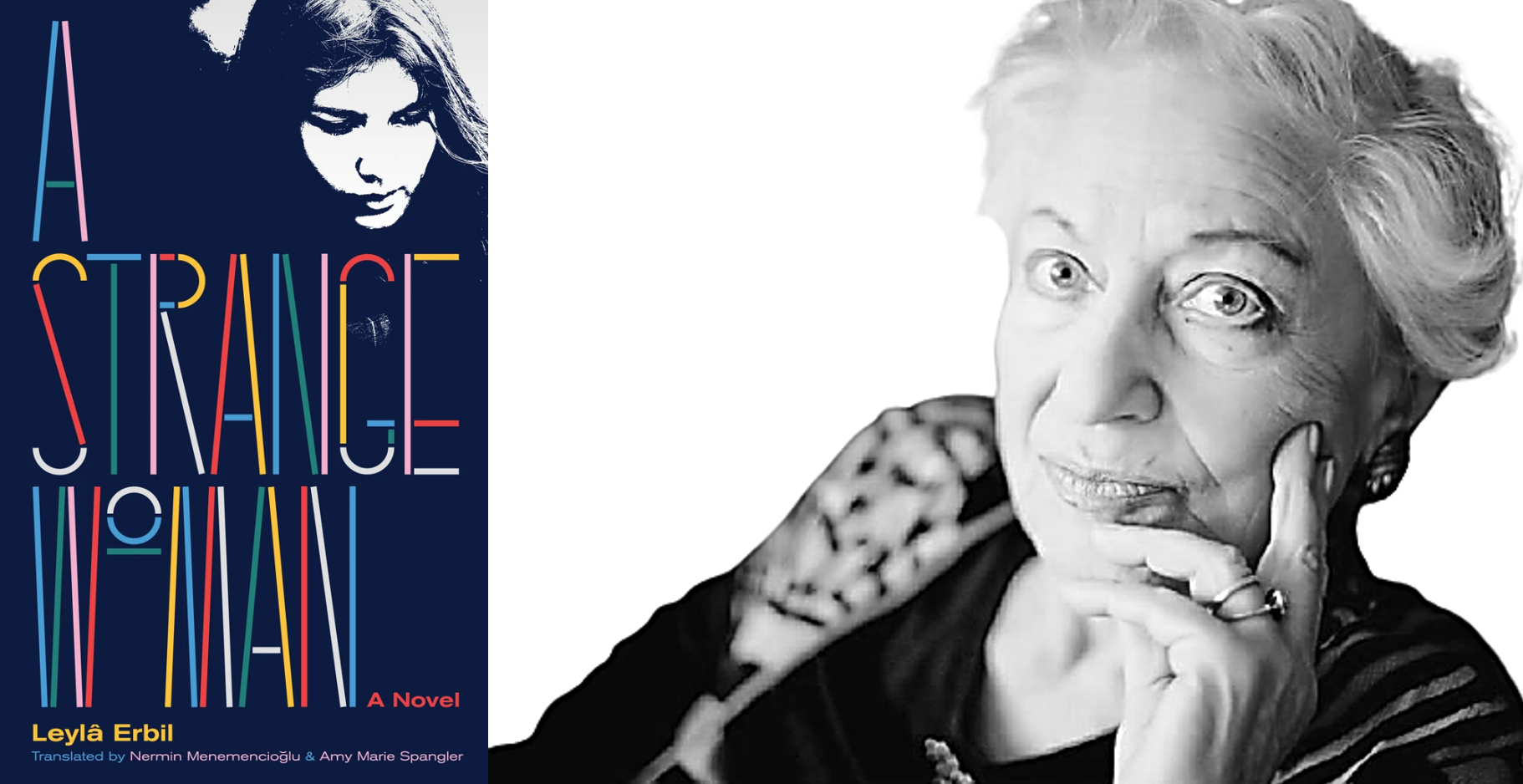

This excerpt from A Strange Woman was published by permission of Deep Vellum Publishing. English translation copyright © 2021 by Nermin Menemencioğlu & Amy Marie Spangler