This is part of our special feature, Displacement, Memory, and Design.

Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof, 1938, children board a train to London. They wave goodbye to grief-stricken parents huddling on the platform. For many families, this was a last farewell; they would never see each other again. 10,000 Jewish children departed the Anhalter Bahnhof in Berlin for safety abroad. Beginning with Hitler’s appointment in 1933, and until the war made flight abroad impossible, for countless other Germans, the Anhalter Bahnhof was their last sight of Berlin.[1] This Bahnhof (train station), and the ruin of what remained of it, served for generations of Germans as a reminder and warning of the utter devastation of the Second World War. Like many other sites in Berlin, the Anhalter Bahnhof carried its own messages amplified by the continuing German engagement with the Nazi past and its continued relevance today.

The Anhalter Bahnhof, located on Askanischer Platz in the center of Berlin, has emerged as a new locale where debates about the German past, its present, and future can be engaged and contested. It is in this very location where histories of exiles collide. This is the case for both “voluntary” exiles—often more privileged German intellectuals who had offers from abroad for asylum, such as from the US, Great Britain, Mexico, Turkey, or various countries in South America—as well as for those forcibly displaced, such as Berlin’s elderly Jews who were deported from there to Terezín. Given that, Anhalter Bahnhof is the perfect locale to reflect on the commemoration of these events, while also putting the difficult history of the country into conversation with the contemporary arrival of tens of thousands of refugees who now seek shelter in Germany.

First conceptualized in 2018, the planned Exile Museum[2] seeks to create a space where histories of exile are documented and showcased. The museum aims to reflect on the word “exile” in general, and what it means for Germany. This includes the confrontation with the current displacement of over 82 million people in the world, and the question of how the exiles of the past and the present relate to the fact that Germany, a country that formerly forced people to leave, now hosts refugees from all over the world.

The museum is scheduled to be built and opened by 2025. The design of the museum and its construction process will be led by the Danish architect Dorte Mandrup, who won first prize in a public and international competition for designing the museum in 2020.

The envisioned design proposal for the Exile Museum. Source: www.stiftung-exilmuseum.de

What makes this particular site at Anhalter Bahnhof with Dorte Mandrup’s stunning design such a poignant location is the fact that right across from this future Exile Museum sits another new museum and place of research. The Museum Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung (The Museum of Flight, Expulsion, Reconciliation) had itself been much longer in planning, but opened just this past July. Its concern is with the millions of Germans who were forced to leave their homes not by their own government, but as part of the postwar expulsion of ethnic Germans from East Prussia, Silesia, and other parts of Eastern Europe. Their story is also being told within the larger context of the ongoing flight and expulsions worldwide.

Given the urgency of the current crisis of worldwide displacement and forced exile, people involved in the Exile Museum and local actors felt the need to begin conceptualizing what the future museum could encompass. A temporary exhibition outside the Anhalter portico, built before even the first construction went up for the new museum, provided a wonderful opportunity to explore themes of exile and to offer the public a taste of what sort of place of commemoration is to come to this location.

In 2020, the Stiftung Exile Museum[3] and Technical University Berlin, with its two departments in the Faculty of Architecture, Planning, and the Built Environment, those being the Natural Building Lab (NBL)[4] and the Habitat Unit,[5] decided to collaborate on this project. The collaboration additionally included other actors, such as the City of Berlin, the Berliner Immobilienmanagement (BIM), and Sans-Serif, which contributed to the development of the concept and also took over the responsibility of preparing the different elements of the exhibition, such as images and text boards.

During the summer semester of 2020 and the winter semester of 20/21, architecture students at the TU Berlin started planning, constructing, and designing this temporary exhibition using six containers donated by the BIM and the Landesamt für Flüchtlingsangelegenheiten (LAF), which is the main organization responsible for administering refugee accommodations in Berlin. The resulting exhibition was the product of collaborative efforts of all these actors, a process that was especially challenging due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Much of the design process had to take place online using digital platforms, and the exhibition finally opened on June 12, 2021. ZU/ FLUCHT, a wordplay in German literally meaning both “zu Flucht: about flight” and “Zuflucht: to seek refuge,” is an outdoor exhibition on the path leading to the future site of the Exil Museum. The ZU/FLUCHT exhibition creates a transitional phase between the empty space around the ruins, and the future permanent museum. It brings attention to current issues related to migration and refuge. The choice of materials used for the exhibition was made to in order to demonstrate how the histories of displacement, migration, and dispossession from the past and present intertwine.

The ZU/FLUCHT exhibition as it appears in front of the portico ruins of the Anhalter Bahnhof. Source: Till Budde/ Stiftung Exilmuseum Berlin.

Design: Building with Containers

The construction of the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition relied on six container units that were donated to us by the BIM. These containers were taken from what is known in Berlin today as “Tempohomes”: a special type of refugee camp designed and built across the city when tens of thousands of refugees arrived beginning in 2015/16. The name suggests the planned temporality of the refugee housing (similar containers can also be found on construction sites). These donated units used to accommodate refugees within their walls. They witnessed the stories, sorrows, struggles and ambitions of refugees to build new lives in Germany.

During the planning phase for the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition, the students raised the following questions: How could a container that had been used within a Tempohome “settlement” be repurposed and remodeled for this exhibition? Is the container made of a durable and sustainable material as one might expect, because of their similarity to the shipping containers? During this examination phase the students gathered all technical information about the container. To do this, one of the six containers got transported to “Ackerstraße” a branch-hall of the Technical University. To understand its construction, the container was completely dismantled and every bit of material was documented. Contrary to the expectation that the container would be a solid construction, the material, mainly folded metal profiles used as beams and columns, could only work for the purpose it was designed for. Stacking or flipping the container would not be an option for the planned temporary exhibition. With this newly gained knowledge, the design phase began.

Since the exhibition would be public, open air, and without on site security, restrictions imposed by the city and availability of space also influenced the design. The students were advised by the City of Berlin not to create any “roofed corners” so that the exhibition would not become an attraction point for homeless people at night, and thus be misused. Moreover, the exhibition needed to be properly solidified and built, without digging and fasting it into the ground since it is only temporary. To design with the existing material and as sustainably as possible, all material that could be used from the containers was included into the design. Wall panels were used as information boards and one container body was to serve as a stage to host speakers, or discussions. The team presented a first design approach in July 2020.

The container being materially explored and examined by the students. Source: Matthew Crabbe / Natural Building Lab.

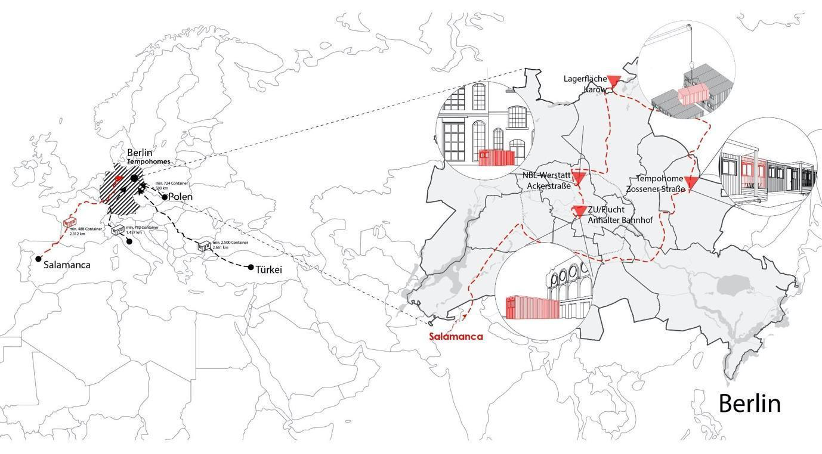

The trajectory of the containers showing how they circulate and ended up in the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition. Source: Authors

In the following semester, and in order to finalize the design and begin the implementation planning, the students developed new methods and formats in self-directed learning, which led (among other things) to the founding of their own project office with the name “Studio dazwischen” (“Studio In-between”). During the project, they worked with experts from the fields of architecture, urban planning, structural engineering, communication design, and cost planning. As researchers from the working group Architecture of Asylum, we also accompanied the whole process throughout, joining meetings and providing feedback on design and how to best incorporate the container as material for the exhibition.

Using Containers: Refugees in Berlin Today

As mentioned above, to provide shelter for the large numbers of refugees arriving in Germany and Berlin in 2015, a special construction policy enabled Berlin refugee authorities to create multiple Tempohome shelters all over Berlin within a short time. This would provide a fast, temporary accommodation solution. Penetrating the urban fabric of the city, these temporary settlements can be found in different areas around the city; some are located in the center close to public transport, others are in well-to-do neighborhoods and in the vicinity of museums. Other Tempohomes were located in low density areas in the outer suburbs of the city, and even planted amongst abandoned high-rise buildings, the so-called Plattenbauten from the GDR.

Tempohome sites were planned to accommodate about 250-500 people. An exception was the Tempohome located at the historic airport in Tempelhof, which hosted around 1,200 people at one time. Although they differ in size, location and site plan, they all follow the same spatial structure: a fenced space, controlled by a checkpoint, they are managed by a relief organization (operator), they include a few shared amenities such as gathering rooms (Gemeinschaftsraum), child care, or washing rooms, in addition to an NGO administrative office. With rows of containers placed to accommodate refugees, the “residential zones” of the Tempohomes are designed according to the container units, their structure, and dimensions. For example, each individual Tempohome is composed of three identical containers (2.3 x 5.9 meters) attached to each other. The unit is accessed from the middle container, being a shared space, and it is used as a small lobby entered through a porch and cantilever, and equipped with a small kitchenette and washroom. Each container is aligned to host two people. Thus, the two adjacent rooms are equipped with standardized furniture. Those can slightly differ based on what the operator would like to offer, but they generally include two beds, two mattresses, two wardrobes, one small fridge, one table, and two chairs.

The design team took note of these dimensions, as well as uses and symbolic meanings of the container while preparing for the upcoming exhibition. In that sense, the reusing of the container material relied heavily on the findings of our research project “Architectures of Asylum” investigating the planning of Tempohomes and the way in which refugees who were housed there between 2018 and 2021 appropriated the space.

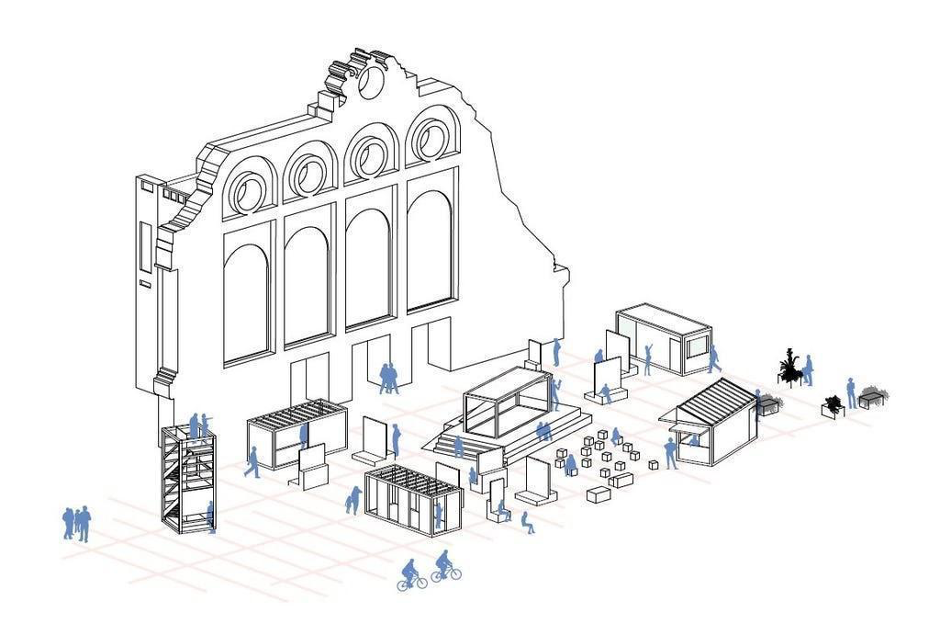

Design: The ZU/FLUCHT Exhibition

Once the exhibition design was developed, the students began the building process in April 2021. The design of the exhibition at Anhalter Bahnhof includes six “stations,” or themes based on each of the donated containers. The premise was to make use of the material the containers provide and to explore the technical possibilities of the container, but nevertheless stick to its original dimensions and see for ourselves how to plan and cope with a small space-forming element of just thirteen square meters. One container was used as a welcoming station. It was raised, flipped, and remodified into a tower next to the portico ruins, offering visitors a detailed overview of the exhibition. Two Containers on the west side of the space were offered information panels about the future Exile-Museum and its architecture. Featured also are large portraits of Germans forced to seek refuge during the 1930s and 1940s; they engage the viewer with quotes about their last experiences as they said their good-bye to the city at the Anhalter Bahnhof. In the center of the exhibitions sits a container that also serves as a stage with comfortable seating areas and the possibility to interact and host events. An information container opens up once a week, to answer questions and offer the opportunity to visitors to submit ideas and suggestions for the planned museum. Questions can be answered or suggestions and wishes toward the upcoming museum can be collected.

In designing the exhibition and the narration of exile, the openness of the area had to be kept in mind. As an orientation of how to assemble the containers, a grid that was used in a previous Tempohome was projected onto the ground and the containers arranged along this grid. Containers that held information about Exile in the past and the future were to be placed within this grid; containers that offer the visitors information about the future of this area were placed outside of the grid.

Moreover, the design of the exhibition was color-coded. Red was used to display elements of the exhibition that relate to experiences of flight and exile today. This includes the ABC of Arrival—the result of a workshop conducted between refugees in Berlin, the Exile Stiftung, and the We Refugees Archive, in addition to the findings of our research project, “Architectures of Asylum,” which we curated to display in one of the containers.

A perspective showing the design of the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition, the portico ruins of the Anhalter Bahnhof and the different spaces created with the containers. Source: Natural Building Lab.

Appropriations and Agency: Architectures of Asylum

This last section will introduce the work and ambitions of the group Architectures of Asylum in more detail and how the Exile-Today Container tries to summarize knowledge gained while visiting refugees living in their temporary homes. Through the lens of architecture, we hope to communicate the complex realities of Berlin’s refugee accommodations through graphics and visualizations. For the Zu/Flucht exhibition we aimed to convey our findings on an abstract level to enable visitors to understand the process of appropriation employed by refugees in their container “homes” but also to respect the privacy of our interlocutors.

“Architectures of Asylum” is a research project that took place at the TU Berlin as part of the Collaborative Research Center “Re-Figurations of Space.” The project looked at the planning of refugee camps and the processes of appropriation of space in three different sites: Zaatari and Azraq camps in Jordan, and Tempohomes in Berlin. During the research phase, we tried to map the different ways in which refugees encounter and confront the limitations of the shelter provided to them. In all three case studies, refugees tried to transform their “shelter” into a “dwelling,” which merged their social and cultural needs with the regulations and physical-spatial conditions in each of these camps. Our intention while curating this part of the exhibition was to showcase refugees’ agency by highlighting the way in which they appropriate the spaces according to their needs and comfort. Many people in Berlin might have passed by a Tempohome in the city, knowing little if anything about how refugees experience these spaces. Therefore, our curatorial concept was driven by an attempt to raise awareness about these refugees’ agency and to highlight their role as co-producers of the space and as city-makers.

One example of this appropriation is a lonely bed frame on the roof of one of the containers, intended to catch the attention of by-passers. Just as we have found it in the Tempohome, the bed is a perfect example of the ingenuity of refugees as they deal with the unfamiliar space assigned to them during their stay in a container-home. Beds take up a lot of space, and because beds are not to be removed from the container, limited space pushes refugees to find creative solutions, like putting the bed on top of the container. Thus, the limits of available space push refugees to find creative solutions, like putting the bed on top of the container. Our research findings from that project were gathered in a short documentary “13 Square Meters”[6] that premiered at the London Architecture Film Festival.

To introduce visitors to the topic, our research project is represented graphically on the facades of the container. On one side is a world map that includes the three case studies: Zaatari, Azraq and Tempohomes. The map also shows the escape routes of refugees, the logistics of the container supply, and a timeline of events and numbers of refugees. On the opposite side of the container is a detailed comparison of the three case studies in terms of space reconfiguration to show how refugees lived in these camps, navigated conflicts and limitations, and found solutions to dwell in different shelter-contexts.

Our curated element at the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition showing the findings of the research project “Architectures of Asylum”. Source: Lisa Starmans.

To highlight the appropriations within the given space and the newly added elements created by the refugees, we used red—in contrast to black, thus making them more visible and highlighting refugees’ agency. These elements include markets, gardens, and, as mentioned above, even beds placed on top of containers so they could not be seen by the officers running the camp.

The same design code is used inside the container. Two panels were cut out of the wall of the container and replaced with glass so that the visitors of the exhibition can see what was going on inside. LAF donated the furniture of one container, which we painted white. Then, using the tape technique, we showed the refugees’ appropriations: a disassembled bed and refrigerators stacked on top of each other, pillows, curtains, rugs, plants, carpets on the floor, etc… On the glass panels, we printed quotes from refugees that explain the reasons for the changes in the proposed standard design, such as lack of space or the prohibition against putting screws into walls. These appropriations were coupled with quotes derived from our research project, trying to give more depth to what is being simply presented with the help of some tape within the limited space of the container.

Appropriations shown in red and black inside the container. Source: Lisa Starmans.

Overlapping Histories of Displacement

Through the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition, we tried to underline the agency of refugees using only one container as an example. By collaborating with many actors, such as the Exil Stiftung, the Natural Building Lab, and Sans-Serif, we faced a challenge; how can the experiences of exile be best portrayed and represented? The reusing of the containers, which were once inhabited by refugees in Berlin, was an example to show this interconnectedness and the circulatory nature of life in exile. A container that used to shelter refugees, where their stories of exile, loss of home, and struggle in a new land were told, is now itself a structure of an exhibition.

This interconnectedness is not only to be shown, but also to be experienced. An important element of the exhibition is its connection to the city of Berlin. So far, many activities and events took place on this site: urban gardening, furniture building, panel discussions, and interactive activities that have included many different actors, including refugees, migrants, artists, architects, activists, and other residents of Berlin. Despite the fact that the exhibition will be dismantled in October 2021 to pave the way for the construction of the Exil Museum, we hope that this short article has provided a glimpse of the challenges and excitement of working with such compelling, provocative, and much-needed topics as exile and migration.

In its own simple way, the ZU/FLUCHT exhibition puts many voices and histories of displacement and migration in conversation with each other. What used to be a place of departure for exile or death, has now become a space for accommodating the stories of exile and displacement of people that have been displaced, such as Palestinians, Syrians, Afghans, Eritreans, Ethiopians, and individuals from many other places of the globe. The refugee and the citizen, the displaced and the settled, the marginalized and the privileged, all circulate in a world characterized by instability, injustice, and messiness. The exhibition poses questions about the nature of exile today, and its interconnection with past German history. Exile continues shaping the human experience and deeply affecting how people experience the world.

Ayham Dalal is an architect, urbanist and artist based in Berlin. He obtained a PhD in architecture with distinction from TU Berlin. Currently he is associated with the project “Architectures of Asylum” at the CRC “Re-Figuration of Spaces” and works on his first monograph “From Shelters to Dwellings: The Zaatari Refugee Camp.” Ayham and his graduate students Antonia Noll and Veronika Zaripova collaborated on this project.

References

[1] Lothar Eberhardt, “Neues Denkmal zur Erinnerung an Kindertransporte”, haGilil, December 1, 2008,

http://www.berlin-judentum.de/denkmal/kindertransporte.htm.

[2] “Museum,” The Stiftung Exil Museum Berlin, The Stiftung Exil Museum Berlin, accessed October 15, 2021,https://stiftung-exilmuseum.berlin/en.

[3] “Museum,” The Stiftung Exil Museum Berlin.

[4] “Natural Building Lab,” Natural Building Lab, Technische Universität Berlin Faculty VI – Institute for Architecture Sec. A44, accessed October 15, 2021, https://www.nbl.berlin/.

[5] Philipp Misselwitz, “About,” Habitat Unit, Institute for Architecture Technische Universität Berlin, accessed October 15, 2021, http://habitat-unit.de/en/imprint/.

[6] “International Film Competition 2021: Shortlisted Films,” Architecture Film Festival London, Archfilmfest Ltd., 2021, https://archfilmfest.uk/awarded-films-2021/