Translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker.

I had a suitcase, that’s it. My mother’s old suitcase with wheels, the one she used to take with her jetting around the Old World for work, till the doctor made her stop flying, because of her varicose veins. It was late July, gruelingly hot, record- breaking temperatures. I forgot my bottle of water on the bus I took from where we lived to the town nearest the Institute. In our town, all we had was a recruitment office. The woman there told me the Institute used to be a meatpacking plant and its cur-rent purpose was ongoing “small-scale” work. It had a capacity of such and such, its own brain trust, and, thanks to the generosity of its (all-female) donors, it could concentrate on its mission without having to compro-mise.

I already knew all that, of course, but the deciding factor for me was the availability of housing for out-of-town employees. My mother was delighted when I gave her the news. “Live your dream,” she said. “And never back down from it,” she added as I grabbed hold of that awful suitcase and walked out the door. It was a quote from a Movement campaign that no one remembers anymore, and even at the time my mother and I had found it a bit silly. Because you have to define what it means to not back down. Otherwise you risk sounding like some Nazi feminist offshoot slash self-appointed dictatorship of spoiled princesses, and nothing could have been further from the truth when it came to the Movement. The clients’ bedrooms are dark. Lights-out is at ten thirty, a policy the clients voted for themselves and submitted for approval, which the board rarely withholds. There’s only one recent case I can think of, a seem-ingly mundane request to have mirrors in-stalled at the Institute, to which the board replied as follows: “We mirror one another within ourselves. Not only women in men and vice versa, but also men within their own sex.” The request for mirrors was denied. The reason the board gave, in typical Old World fashion, was that it would overturn the fun-damental idea of “Looking into the world and at it” in favor of “Looking at oneself with the intention of altering one’s exterior to advertise oneself to others as an object for visual consumption, turning human beings into objects whose exterior is elevated at the expense of what lies within.” I remember the board’s decision seemed a bit overzealous to me at the time, but I now understand and fully approve. The most unyielding walls of the Old World fortress are the walls within our minds. Although the Movement has been triumphant in most of its battles on the battlegrounds of the world (in our latitudes at least), the battles we fight with our own ways of thinking are waged behind the scenes, only after the cur-tain has come down.

The group of clients requesting mirrors tried to counter with the feeble objection “We don’t want to walk around the Institute with toothpaste on our faces,” a weak lob the board returned with a smash, saying they could ask their roommates whether or not they had toothpaste on their face. And when one of the clients responded with the back-handed return “I don’t have any friends here,” the board put the point away with a brisk “Then ask the guards.” Thinking back on it, I have to laugh, since in all my years here no one has ever asked if they have toothpaste on their face, and I always enjoy telling the story to novices at the Institute, as proof that it isn’t only the clients who grow spiritually here, but also the staff, since at the time I had serious doubts about the wisdom of the board’s decision. If I had known that back then, on my gru-eling journey with that awful rattling suit-case, I could have spared myself a few lessons early in my employment, which I had imag-ined would be more like the work of a prison guard in Old World films, looking into cells through peepholes and that sort of thing.

Though, to be honest, that was so many years ago now, I have only a vague recollec-tion of what I imagined my work would be like, and my strong memories are all of how thirsty I was on the trip. The road leading to the Institute from the last stop on the city bus line was the kind that has a sign warning ROAD CLOSED WHEN ICY, but no gate blocking it off. That’s how it was with everything in the Old World. Lies piled on lies piled on top of other lies, and ordinary human stupidity was just one more reason why the unethical environment for the upbringing of girls lasted as long as it did. As we approached the Institute, I saw spots before my eyes and almost took the impos-ing building, divided into several wings and ringed with a thick wall, for a mirage. With all the cars coming and going and the road being practically dirt, I was covered in dust. It surprised me to see such brisk traffic, but the reason would have been obvious if I had stopped to think. How else were clients going to get to the Institute? The stop where I got off the bus was the end of the line, and not everyone could afford a taxi, which in any case was an option only for clients who lived in the next town over, and most of ours came from somewhere else. From places where there was no Institute. Either that or they had chosen ours because of its reputa-tion, short waiting period (admission here, unlike at the smaller facilities, was almost always immediate), and outstanding results (the length of a stay was typically no longer than eighteen months). The Movement never bought into the idea of catchment areas. The freedom to decide one’s place of treatment for oneself is one of the Movement’s ethical maxims, and sometimes, too, the wives de-cide, based on a friend’s recommendation or a visit in person (public days are the first and second Wednesday of every month). In fact, a woman who comes in advance to inspect the facility for herself is the best guarantee of a man’s successful ongoing recovery at home.

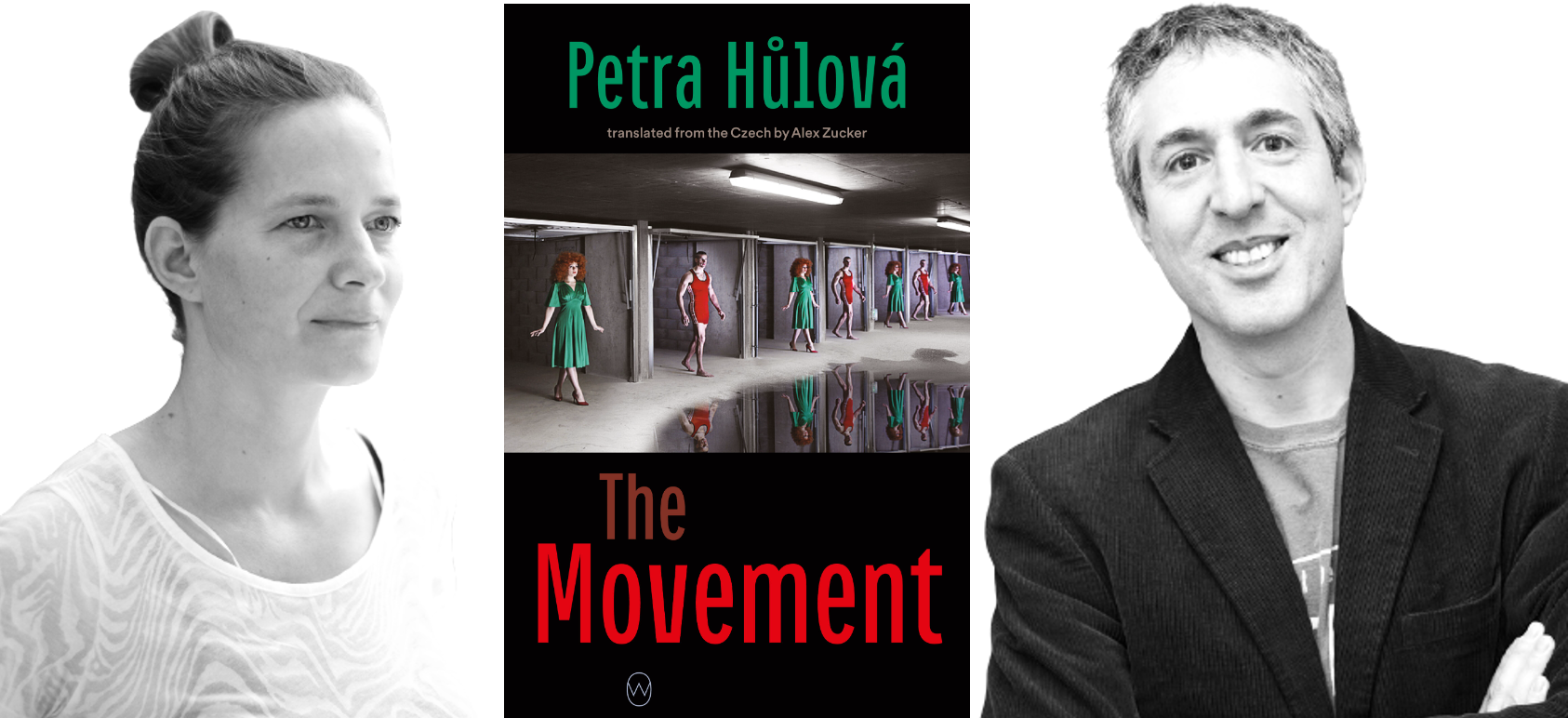

Petra Hůlová’s provocative novels, plays, and screenplays have won numerous awards, including the ALTA National Translation Award for Alex Zucker’s translation of her debut novel, All This Belongs to Me, and she is a regular commentator on current events for the Czech press. She studied language, culture, and anthropology at universities in Prague, Ulan Bator, and New York, and was a Fulbright scholar in the USA. Her eight novels and three plays have been translated into thirteen languages. She used to define her writing as “3G”: always working with topics of gender, generations, and geography. Her novels are often narrated in first person and range from intimate confessions to buoyant epic sagas. The Movement is her latest work.

Alex Zucker’s translations include novels by J. R. Pick, Jáchym Topol, Magdaléna Platzová, Tomáš Zmeškal, Josef Jedlička, Heda Margolius Kovály, Patrik Ouředník, and Miloslava Holubová. He has also translated stories, plays, young adult and children’s books, essays, subtitles, song lyrics, reportages, poems, and an opera. His translations of Petra Hůlová’s Three Plastic Rooms and Jáchym Topol’s The Devil’s Workshop received Writing in Translation awards from English PEN, and he won the ALTA National Translation Award for Petra Hůlová’s All This Belongs to Me. He lives and works in Brooklyn.

This excerpt from The Movement was published by permission of World Editions. Copyright © Petra Hůlová, 2019. English translation copyright © Alex Zucker, 2021