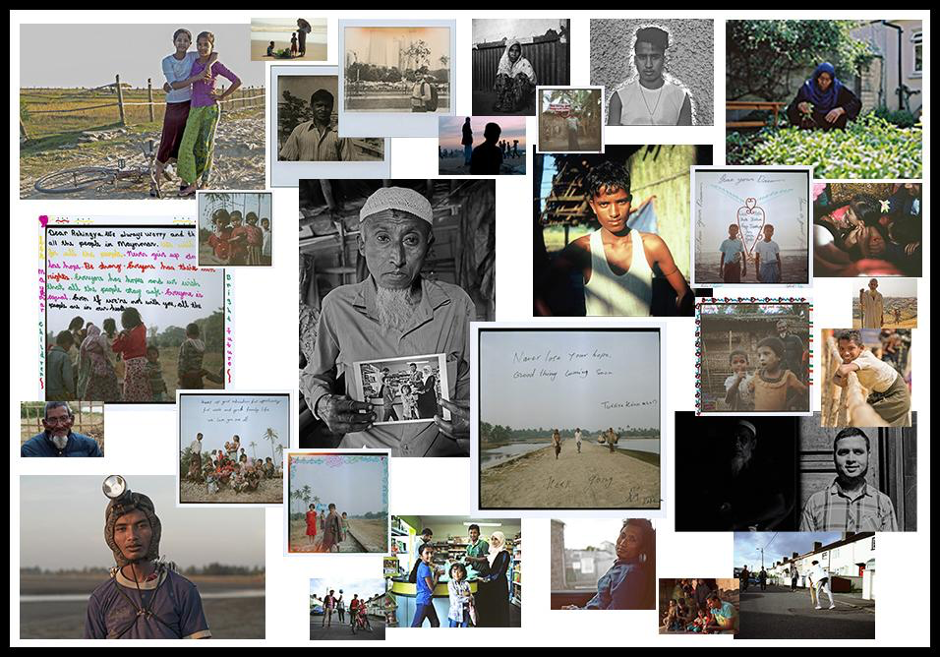

This is an introduction to our Campus Spotlight on Sarah Lawrence College, and part of our special feature, Displacement, Memory, and Design.

Rohingya communities from Myanmar are spread around the world. Separated families create networks to preserve cultural heritage, build belonging, and imagine futures together. This project visualizes how these networks of connection are making meaning amidst adversity.

Bridges is a visual anthropology project made collaboratively with Rohingya communities living in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, Malaysia, and Europe.

Find the first part of this project, which began with research and multi-sited fieldwork as a student at Sarah Lawrence College and during the Meredith Fonda Russell International Fieldwork Fellowship here. Some names have been changed for privacy and protection.

With over 80 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide at the end of 2020 (UNHCR, 2021), there is an increasing need to understand how communities living across borders are staying connected. While mass-media has the widest influence in shaping our image of groups of people, efforts towards participatory image-making and storytelling are an effective way to engage, catalyse, and make visible the agency of communal networks. The ethnography project Bridges (Cerretani, 2018) interweaves experiences of refugeehood through multimodal messages exchanged between transnational Rohingya families. Barriers are crossed by way of photo-textual objects. The families I worked with experienced a protracted refugee situation beginning in 1992, when the Burmese military forcibly displaced Rohingya to Bangladesh.

I began using photo-messages as a method in 2017, with the Rohingya community in Ireland (RCI). Upon graduation from Sarah Lawrence College, I was granted the Meredith Fonda Russell International Fieldwork Fellowship. The fellowship gave me the chance to immerse myself within the lifeworlds of the Irish Rohingya by living and working together through the anthropological tradition of participant-observation. The RCI is around one hundred persons who were displaced from Myanmar in 1991-1992 during what the Burmese military referred to as, “Operation Clean Nation.” These families subsequently spent seventeen years from 1991-2009, living in various camps on the Bangladesh side of the Naf river which borders Myanmar, before resettling in Ireland. The photo-messages method makes records of bridgesbetween networks that persist to proliferate despite the geographic separation, which Rohingya and other people from the Burma face as part of the far-flung nature of refugee experiences. During the process of making photo-messages an understanding of the formation and maintenance of relationships emerges. The Rohingya community in Ireland all have family in Myanmar, Bangladesh, and spread around the globe. The modes and means through which families facing protracted refugee situations connect can help to understand how these bridges are built and maintained.

While living with the Rohingya community in Ireland, I became more attuned to the ways we regularly used our phones and computers to share combinations of text, audio, and images– both moving and still. Sending such messages through the evolving shapes of platforms like WhatsApp, Messenger, Twitter, Telegram, Instagram, Tik-Tok, and WeChat has become such a regular practice, one with limited reflection, that the phenomenon of sharing and conversing around images are obscured.

Fig. 1 Rabeya, a matriarch in the Rohingya Community Ireland picks Muli-Fatha (Radish leaves)

The rate at which new images appear on these platforms and are subsequently crowded with comments or become cause for conversation are then replaced with new iteration of post, story, message, or meme, is understudied regarding its implications for how groups of people are visualized. Whether it is the creation of static or homogenous categories that reduce an identity rather than representing its iridescent nature or the inventive ways in which transnational communities use social media to maintain identity. The photo messages method centres around process, while opening a phenomenological view into the frenetic pace at which digital messages move through spatiotemporal realms.

Photo-messages look at the minutiae of meaning making—the mechanics of photo elicitation, the affective reflections that form conversation, and the addition of text, drawings, discussion, and storytelling that emerge through a slowing of the process of message making and exchange. Participant observation is foundational to the process of making photo-messages (Jackson, 2002). Photo-messages build on the groundwork of anthropologists, artists, and interdisciplinarians while centring around inventiveness and collaboration to work towards, “an understanding of cultural meaning that is heterogeneous, fractured, and dislocated” (Dattatreyan and Marrero-Guillamón 2019: 222). The output of workshopping photo-messages are physical photo-textual objects. However, it is the collaborative process of making them in which multimodal layers of labour, performance, and storytelling, converge into a textured experience. The objects travel, making a snapshot-representation of the existing networks and new synapses which are constantly connecting. From there an archiving of the events that unfold as the physical objects are delivered is detailed through a “follow the thing” method (Appadurai, 1988; Wright, 2013).

The embodiment of a photo-message imbues it with traces of the lifeworlds through which it is gestated, labored, and delivered including the ambiguities around representation and capital. The commonality at which we find the global in the local, and the rate at which the local is transmitted across the world has transcended the multi-sited anthropology framing put forth by George Marcus (Marcus 1995). Anthropologists are now seeing relationships in a more networked vision of spatio-temporal connection (Arnold 2021; Campt, 2017; Nakassis, 2018). With the instantaneous “sharing” of images and the potentially elastic expansion across networks, the conditions under which representations of groups are made in relation to their referents need be (re)considered.

After some weeks of living together, Rafique and other community leaders asked if I would work with them to engage with the youth in the community through filmmaking, screenwriting, and photography projects. From there we collaborated to facilitate conditions which explored what visions participants had. In Ireland, I began to gain more insight into the politics of representation among Rohingya. Photos and video depictions of Rohingya, particularly violence against Rohingya bodies were prevalent in the quotidian experiences of my host family. The living room was an 24/7 newsroom, where Rafique received hundreds of messages daily, many videos and photos sent directly from Rakhine State, Myanmar where ongoing violence against Rohingya was occurring. The experience of seeing these images directly from their source, and having their context explained to me by Rafique before seeing them appear on social media, and then international media drew me to deeply question the way Rohingya were being represented, and the cyclic relationship of marginalization to mediatization.

Fig. 2 Rafique’s father in Kutupalong refugee camp with a picture of the Rafiques buying grocery in Ireland.

Representations of Rohingya exiling from Myanmar to Bangladesh which were channelled through mass media outlets stood in contrast to the moments of family-life that filled the same living room in which some of those images first surfaced from Rakhine State. The bonds of these transnational families and the Rohingya community at large are maintained around the clock, with constant calls, messages, audio clips, and audio-visual materials bouncing back and forth from Burma, and Bangladesh—where Rohingya were fleeing to escape the pogroms. It was clear from the way in which my host family harboured me, an outsider, through their welcome reception, daily hospitality, and patient show of care, what the values of a Rohingya household were. Care, concern, and connection were constantly performed through the sharing of meals, stories, images, and memories. Arnold (2021:139) describes this labor among Salvadoran families:

Through cross-border communication, transnational families carry out the everyday labor of care that keeps them together despite political-economic and discursive forces that would tear them apart.

Fig. 3 Robi and Ismail sketch a phoenix using an image from a cell phone as reference before drawing it on a photo-message that was later brought to two brothers living in Myanmar see fig. 7

I began to think about the relationship between care and a politics of vision, I wondered what would happen when the intimacy of images is broken along the bridge of hermeneutics from interpersonal to international media. The phenomena in which people actively engage with such images through a cultural-capital optics could be called a “politics of vision.” An economy of images in which people show their interest in a subject and apply value based on how long one chooses to engage with the image, how it is shared, and where it is traded. In the case of images deemed abject by the viewer, if they become image—averse or not willing to look at the images at all, does this have a direct relationship to the value, interest, and willingness to engage with the subject? What is the power of violent images that go unseen? Thinking through the micro processes which cause people to pay attention or to look away from things more broadly brought me to ruminate about what other form of representation would contribute to a more heterogenous set of representations of Rohingya (Nursyazwani and Prasse-Freeman, 2020).

A large portion of my fieldwork in Ireland during the summer of 2017, was spent in the living room of my host family where Rafique and I sat with our laptops open and our phones at our fingertips. We were constantly receiving and interpreting photos, videos, accompanying text, and audio recordings from news informants in villages in Rakhine state, ground zero for the Myanmar military’s genocidal actions.

The military’s violence peaked during my stay in Ireland and on August 25th the living room lights never turned off. Rafique hardly went upstairs to sleep as the calls coming in from his contacts were now mixed with those of family who were uprooted or sharing news of the death of loved ones. Seeing these network activate across the globe conveyed a shrinking of geographical space and a convergence of temporalities. Not only were families like the Rafiques straddling both Irish and Myanmar time zones, they were also experiencing time flux similarly to their intercontinental-kin. This shared temporal state was relative to the momentary events of their families as they were fleeing the genocidal military. The strength in the multi-layered web of community members living together in diaspora and their families in Myanmar, Bangladesh shone through these endless evenings.

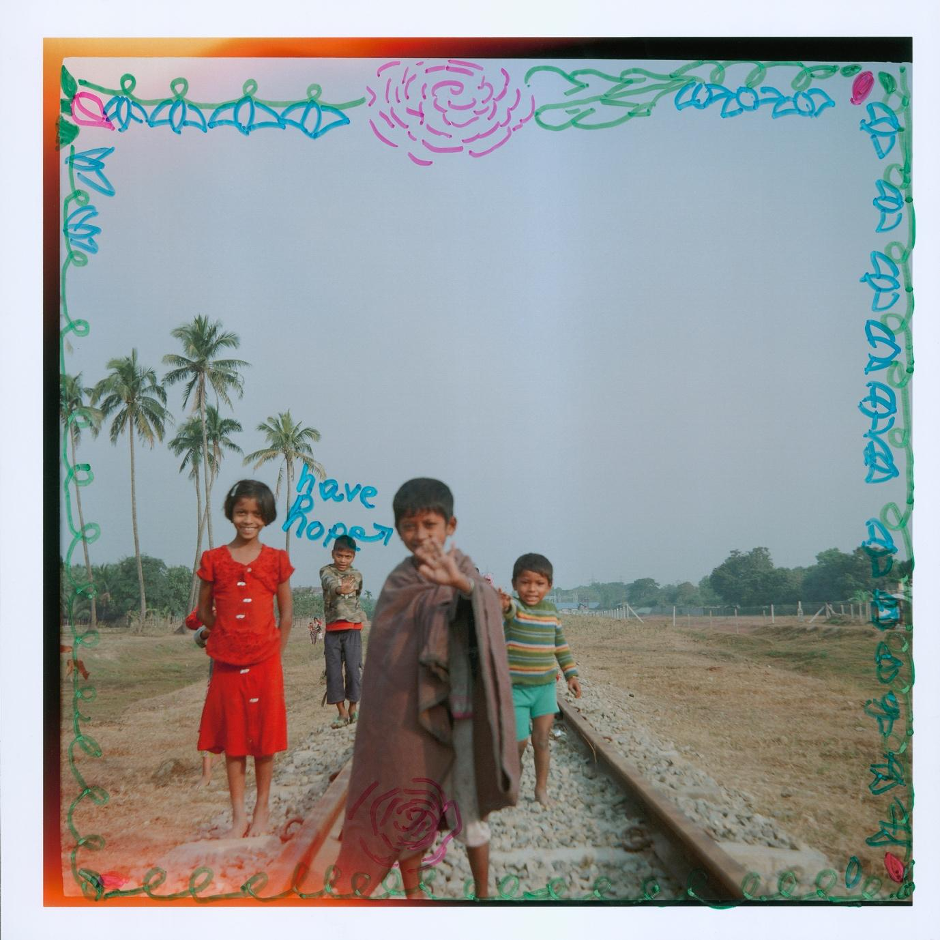

Fig. 4 “have hope”- Jamalida

During the coming together of the local Islamic community on Eid al-Adha, just a few days after August 25th, I witnessed a view of Rohingya which was obscured by the current news cycle’s depictions of suffering, and persecution, instead I saw dignity, resilience, and agency. This latent image came through to me as the clearest one depicting the multiplicity of the human condition and pointed towards the nascent spectrum of representation of Rohingya as opposed to the homogenous reduction of millions of individuals into subjects of a crisis framing which were produced and reproduced by mass media actors (Forkert et al., 2020).

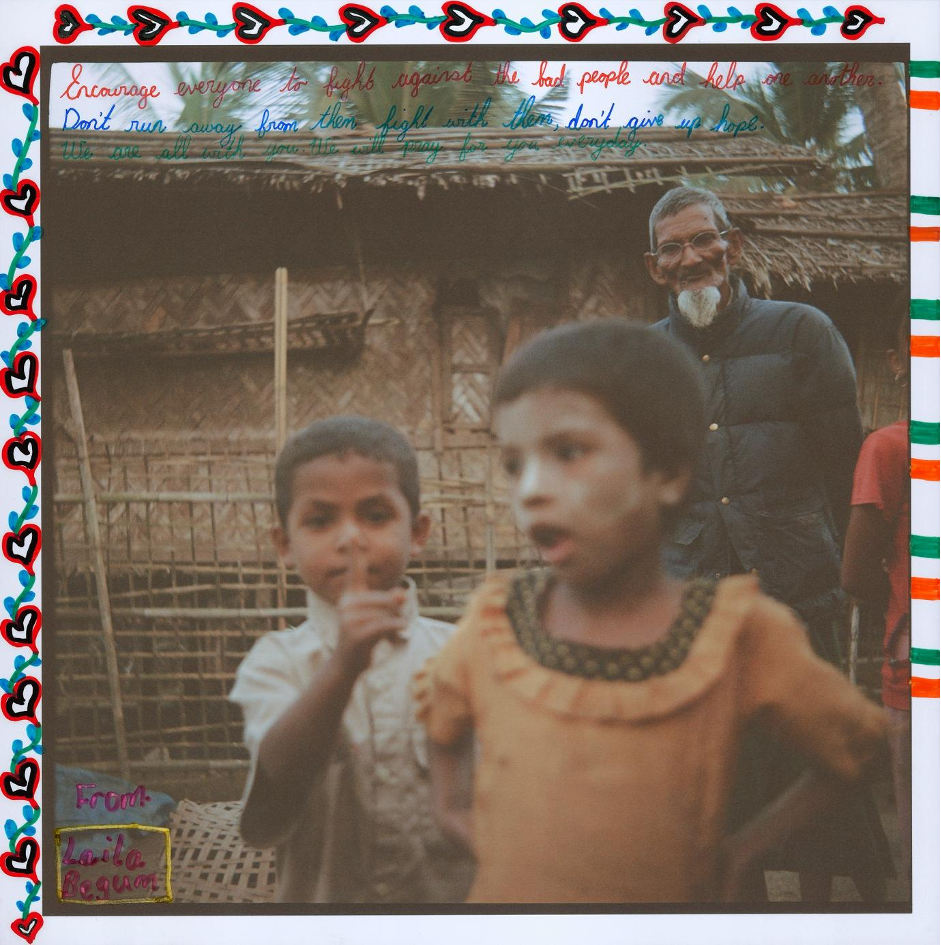

Fig. 5. “Encourage everyone to fight against the bad people and help one another. Don’t run away from them fight with them, don’t give up hope. We are all with you. We will pray for you every day.” -Laila

Seventeen participants from ages fives to fifty were involved in the first photo-messages workshop. It was an open form of collaboration, with an emphasis on process. We had previously discussed the exercise and the participants arrived enthused to have a creative outlet. We worked with large prints, discussed the pictures, and everyone took time to choose a photo, then worked together organically. The choice of the photos gave insight into the parallels and connections by which we see ourselves in others. Nearly all the participants commented about their choice of photo by saying how they felt connection to the people in them.

Fig. 6. It’s worth more than the most expensive dime. Don’t think is it a waste of time. All your efforts are unforgettable. The power of unity is unimaginable. Always keep in mind that there is hope. Never give up. Don’t let anyone keep you from what you want to do. – Sisters, Jamila and Kuslsum

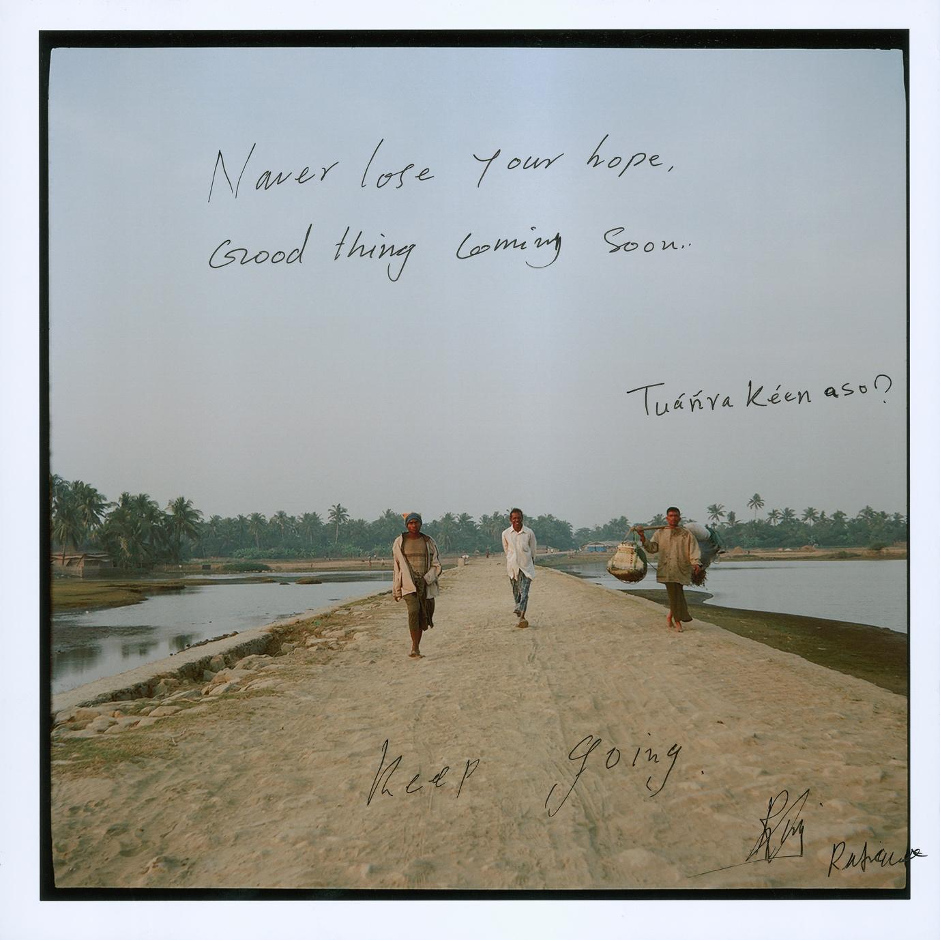

Brothers, Robi and Sofiat wrote a message to another pair of brothers who live in a cordoned off camp on the outskirts of Sittwe, Don’t lose your Dreams. Live your Dreams. Don’t Hate, Think Positive, Keep Reaching for your Goal. Have a good future. (see fig.7). We discussed the people and places in the photos that were made in the peripheral villages around Sittwe, Myanmar which elicited an excited response from Rafique, as he was born in a village in the Sittwe Township. He chose to write his message on a picture of a few men similar in age who were walking down a path towards the Bay of Bengal.

Fig. 7 Don’t lose you Dreams. Live your Dreams. Don’t Hate, Think Positive, Keep Reaching for your Goal. Have a good future. -brothers, Robi and Sofiat

Some of these messages highlighted participants’ agency to (re)imagine futures (Valentine and Hassoun, 2019). Rafique wrote, Never lose your hope. Good thing coming soon. Keep going. Tuáñra Ken Aso?” (see Fig. 8) The dialectic between the encouraging sentiment in English and the simple, intimate inquiry in the Rohingya language, which translates to “How are you doing?, is representation of the care and connection around Rafique’s broader engagement with his community.

Fig. 8 “Never lose your hope, Good thing(s) coming soon.. Tuáñra Kéen aso? Keep going- Rafique

The initial photo-messaging workshops in which members of the RCI started with an open-format photo elicitation exercise, followed by making some drafts of words and drawings by placing a plastic covering over the photo to practice some ideas, before putting ink to the pictures and writing out messages on the photos. Two sisters wrote a message to a group of

sisters who were living in an internally displaced persons camp in Myanmar (see fig. 6). Rafika, a matriarch in the Rohingya community Ireland who wrote to a family in Sittwe, the capital city of Rakhine state, Myanmar (see Fig. 9). This was also a moment for the RCI to see pictures of Rohingya in Myanmar that elicited a variety of responses which differed from those associated with the images of violence. In Rafique and Rafika’s case the places brought up memories of their childhood. A couple of the Rohingya youth asked their aunties and uncles—colloquial Rohingya terms for elders in the community—about village life for Rohingya and learned more about what it was like in Burma since they were born in the refugee camps across the Bangladesh border.

Five months later I met up with Rafique’s family in the camps of Bangladesh and brought them photos of Rafique, Rafika and their children. Similarly, I met with other relatives of the families in the Rohingya community Ireland sharing photos over tea. The connection and reaction to these photos made me to decide to continue the photo-messages method with a family focus. Since then, I have been extending this project to work with transnational families between Bangladesh and Malaysia.

On February 2, 2021, the Burmese military launched a Coup de Tat. The increase in military violence in Myanmar means more people are forcibly displaced every day. The Bridges project and photo-messages method are miniscule in scale compared with the constantly increasing need to understand how families and communities are staying connected in times of crisis. The photo-objects produced in the workshop were a tangible representation of the work that the international Rohingya community does to support one another in imagining their futures and creating belonging around the world.

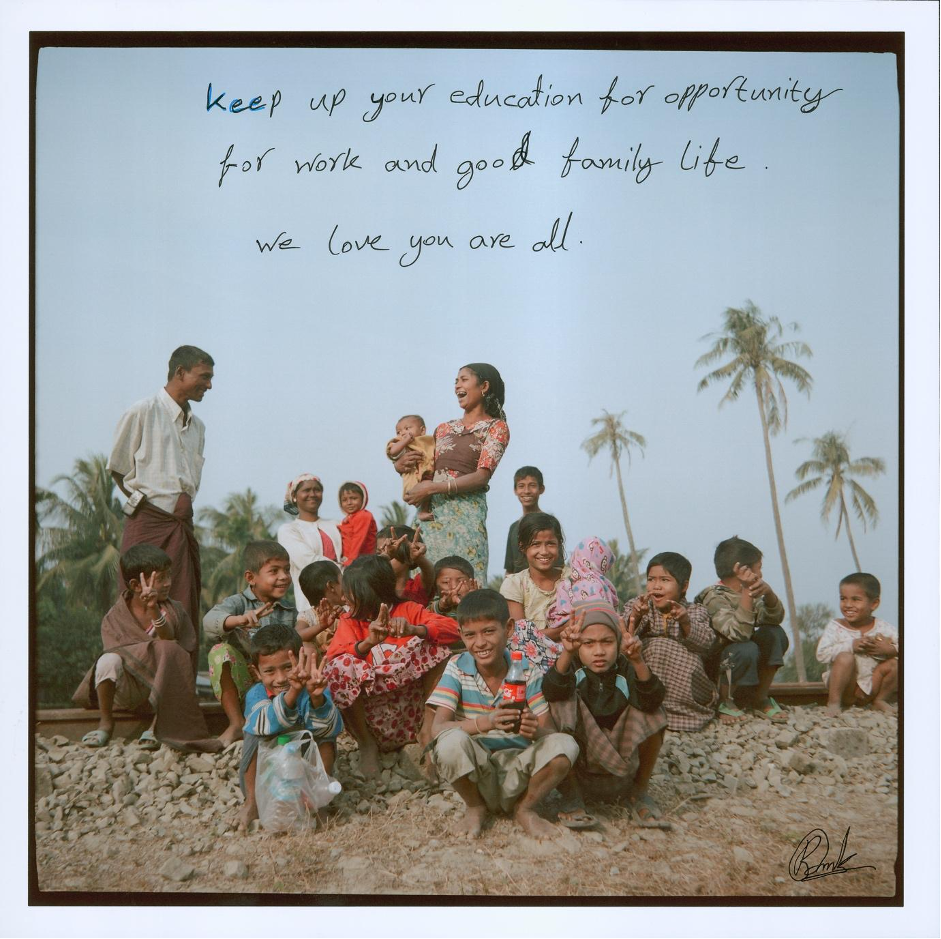

Fig. 9 “Keep up your education for opportunity for work and good family life. We love, you are all”- Rafika

My studies at Sarah Lawrence College instilled within me a mix seminal theory, and skills that has given me the confidence to pursue my work with passion, diligence, and empathy. The Meredith Fonda Russell International Fieldwork Fellowship granted me the most significant summer of my life and a chance to continue my work beyond my time at Sarah Lawrence. I learned a lot through process and development of this project. I have implemented new approaches and techniques while keeping an open approach to what each person brings to the table. The entire Rohingya Community Ireland, and especially my host family the Rafiques, imbued this project with the spirit of humanity. I am currently pursuing a Masters of Research degree in Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London and staying connected with the Rohingya communities I have built relationships with.

James Francis Cerretani is a postgraduate researcher in Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London and practicing artist from New York. Their research with transnational Rohingya communities centers around belonging through practices of art & education. Their work aims to interrupt hierarchies of knowledge production through multimodal approaches to anthropology like participatory youth cinema. James attended Sarah Lawrence College in New York where they worked interdisciplinary across anthropology, filmmaking, narrative photography, and Islamic studies with a regional focus in Southeast Asia. In 2015, they studied history, art, and migration in Berlin, Germany as a United States Institute for International Education scholar. In 2017, James was awarded the Meredith Fonda Russell International Fieldwork Fellowship which supported their fieldwork with Rohingya diaspora in Ireland.

References:

Appadurai, A. (ed.) (1988) The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arnold, L. (2021) ‘Communication as Care across Borders: Forging and Co-Opting Relationships of Obligation in Transnational Salvadoran Families’, 123(1), pp. 137-149.

Campt, T. (2017) Listening to Images. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cerretani, J. (2018) ‘Bridges’ Available at: https://www.sarahlawrence.edu/magazine/global-citizen/media/feature/bridges_cerretani_101118.pdf

Dattatreyan, E.G. and Marrero-Guillamón, I. (2019) ‘Introduction: Multimodal Anthropology and the Politics of Invention’, American Anthropologist, 121(1), pp. 220–228.

Forkert, K., Oliveri, F., Bhattacharyya, G. and Graham, J. (2020) How media and conflicts make migrants. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Jackson, M. (2002) Politics of Vision: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Marcus, G.E. (1995) ‘Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, pp. 95-117.

Nakassis, C.V. (2018) ‘Indexicality’s ambivalent ground’, Signs and Society, 6(1), pp. 281–304.

Nursyazwani and Prasse-Freeman, E. (2020) ‘The hidden heterogeneity of Rohingya refugees’

Valentine, D. and Hassoun, A. (2019) ‘Uncommon Futures’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 48, pp. 243–260.

UNHCR (2021) Refugee Population Statistics Database. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/(Accessed: 24 September 2021).

Wright, C. (2013) The Echo of Things: The Lives of Photographs in the Solomon Islands. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.