“Eurotrash” Films, Hollywood, and the Possibilities and Limits of YouTube as a Media Archive for Popular European Film History

This is part of our special feature on European Culture and the Moving Image.

In 1992, Richard Dyer and Ginette Vincendeau published an edited volume of essays entitled Popular European Cinema. The notion was new at the time, they argue in the introduction. Up to then, popular film in general was associated with the Hollywood film industry and the United States, while European film was linked to “high art” or auteur cinema. Once the existence of some form of popular European cinema was acknowledged by scholars, an interesting new question emerged: What was the relationship between popular European cinema and Hollywood?

A convenient and revealing way to approach this question today cannot ignore a new medial institution that did not exist in 1992: YouTube. YouTube has become something of a platform for the exploration and diffusion of what Dyer and Vincendeau referred to back then as ““low-brow” types of [European] popular entertainment”(1938) and what today is affectionately referred to quite broadly as “Eurotrash” or “Euro-sleaze” cinema—not new productions, but old European co-productions from the sixties and seventies classified under such diverse labels as “Giallo”(Italian mystery/horror), “Eurocop,” “Eurospy,” “Eurohorror,” spaghetti western, and other genres. Today, much of the revival of these often dismissively labeled films and the recognition of their importance for the transnational history of popular culture is a direct result of their increasing availability on YouTube. Particularly in the last decade, YouTube has developed rapidly and become a bottomless repository of privately-owned old films uploaded by fans. Whereas a quarter of a century ago, there were few ways to access these materials, today YouTube can be credited with creating a global circulation mechanism for a wide array of visual documentation, again, made available by fans. In their study YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture, Jean Burgess and Joshua Green have labeled YouTube’s function as a repository as that of an “accidental archive” (2009, 86-90).

What is being “accidentally archived?” I’d like to argue that fans uploading and responding to old popular European genre films are in the process of creating a new basis for a more appreciative and inclusive history of European popular cinema—one that is not and never was merely a low budget knock off of Hollywood, but rather a partner, mirror, alter-ego, and mutual influence; different from Hollywood and more than worthy of its own history.

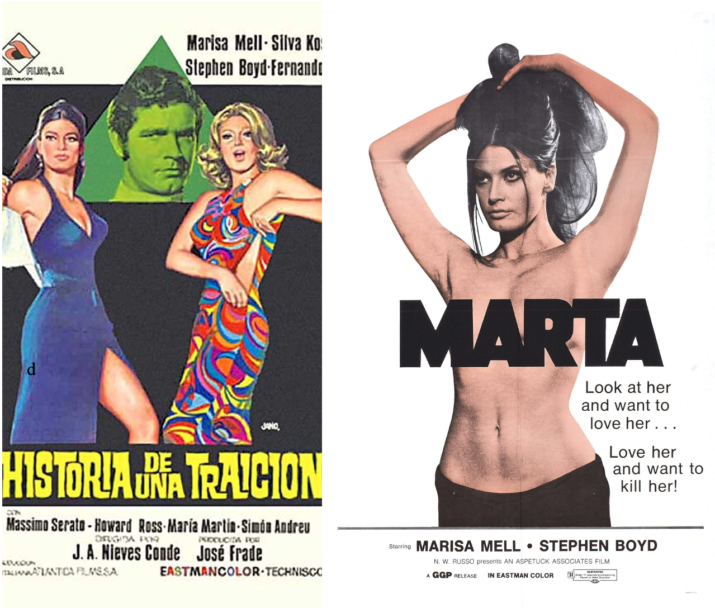

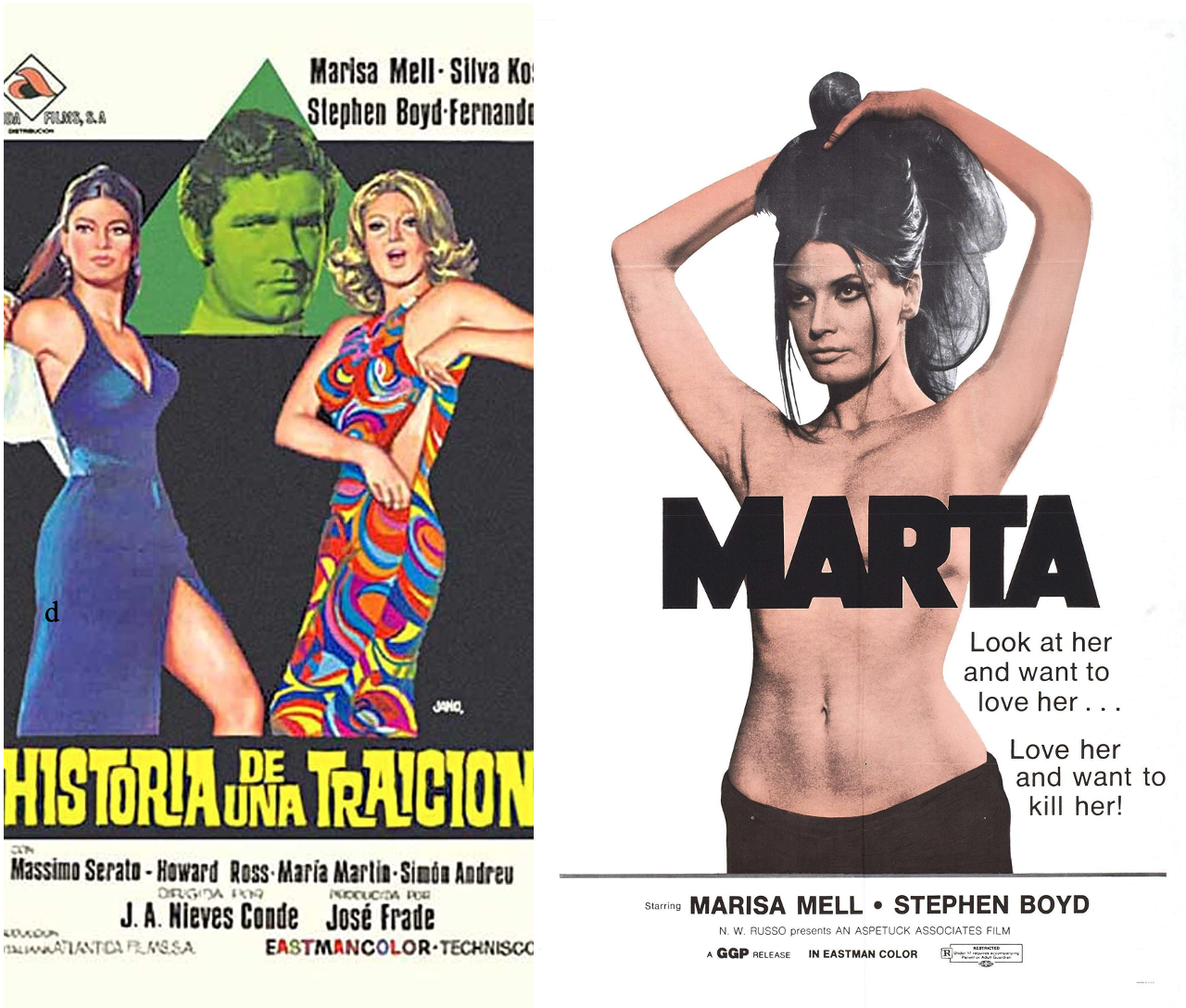

Certain European co-productions of the 1970s as “accidentally archived” on YouTube, such as Marta (1971) and Historia de una Traición (The Great Swindle 1971) seem to be particularly representative of this European alternative to the Hollywood version of popular culture. Its chief characteristics are related to a playful, low-tech appropriation of Hollywood genres (formerly known as “exploitation flicks”), a theatrical, actor-centered, colorful, sensual, and erotically oriented approach to social and sexual interaction, all embedded in a soundtrack of pop, easy jazz, and lounge music. Auteur cinema is replaced by genre cinema; thus, Hollywood is omnipresent, but it is defamiliarized, no longer a star machine, but a source of faces and formulas that suddenly appear in much less stylized, less “controlled” contexts, more human, less unreachable. When Stephen Boyd watches Marisa Mell doing a striptease in The Great Swindle, we are light years away from the polished, lofty, and censored Hollywood studio productions like Ben Hur (1959), which had made Boyd famous worldwide. There is less “high seriousness,” less pontificating. More fun. And more nudity.

This is the compelling nostalgic fantasy that is being created on YouTube about films that were produced in Europe (primarily Italy, Spain, and France) in the seventies, using “waning” stars whose days in Hollywood were numbered, as the story goes, exploitative depictions of female bodies, and low budget production values borne of little infrastructural support. Watching examples of such films today on YouTube, I am reminded how off-limits they would have been to me; too sexually explicit for a Catholic teenager of the 70s. Today, these films may still be considered soft-core pornographic by some, but many more will no longer register these images as such; instead, they have become rather elegantly and tastefully erotic when compared with the more explicit and hardcore imagery now standard even in “mainstream” productions. The focus of the camera is primarily on faces, followed by breasts, legs, and chests.

Let me turn now to my examples: two “Eurotrash” films, best understood in relationship to each other, both made in the early 1970s: the Spanish/Italian co-productions Marta (1971) and Historia de una Traición (The Great Swindle, 1971). These films were directed by the Spanish director José Antonio Nieves Conde (1911-2006) and produced by the Spanish producer José Frade. Each film co-starred the Irish-American actor Stephen Boyd (1931-1977), remembered almost exclusively for his portrayal of the villainous Messala in William Wyler’s 1959 Ur-Hollywood spectacle Ben Hur, and the popular Austrian “Eurotrash” actress of the 1970s, Marisa Mell (1939-1992). All of these figures—actors, producer, director—have been largely forgotten today. Though both films were made for Spanish-language audiences, “international” English versions were also circulated, as well as Italian versions. All versions would be subject to censorship for erotic content in their respective countries, which would lead to diverse forms of cutting and editing to ensure market access, often at the expense of narrative logic. Back in the 70s, the backbone of moving image circulation along with television was still theatrical release. VHS (Video Home Systems) was in its infancy to say nothing of YouTube.

Let me operationalize what I mean by “largely forgotten.” The sixth edition (2008) hardcopy of The Film Encyclopedia: The Complete Guide to Film and the Film Industry by Ephraim Katz and edited by Ronald Dean Nolen, contains no entries for J.A. Nieves-Conde, José Frade, or Marisa Mell. These important figures of European film were simply no longer on the Hollywood radar, if they ever really had been. Stephen Boyd’s brief entry ends with the sentence: “In the early 70s he appeared mainly in bottom-budget Spanish films.” (2006, 169) When Boyd died suddenly of a heart attack in 1977, VHS was just beginning in earnest; what would become of these “bottom budget Spanish films” and others like them was in the stars. Hollywood-oriented international film aficionados like Katz, et al would decide upon their fates through exclusion from such “complete film guides,” as well as through dismissal of content based upon low production values.

Nonetheless, in the late seventies and eighties, these films went into VHS production in forms that are resurfacing on YouTube in digitalized but largely unrestored form. The resurgence of interest in the European genre films of the 70s is linked to the rediscovery of such “Eurotrash” directors as Mario Bava and Lucio Fulci in the 1990s, as well as to scene and plot citations in the US films of Quentin Tarantino (Schneider 142-43; 171-72; Cairn “Once Upon…”). But it is YouTube that is making possible an audience-driven global re-circulation in ways very different from their original theatrical circulation in the early seventies, or their VHS circulation in the eighties. Fans of the films are collecting the available videos and interacting online via blogs and internet databases; they are writing books and publishing them independently; they are uploading and digitalizing old content; once it was technically possible to upload full-films on YouTube, more and more of them began to appear, in addition to excerpt uploads, music videos using scenes from the films, film reviews, etc.

Both Marta and Historia de una Traición (The Great Swindle) broadly classifiable today as “erotic thrillers,” are beneficiaries of creative fan labor to restore, archive, and re-contextualize these films in terms of a more appreciative European popular film history. In 1971, they were products of a fruitful collaboration between the respected Spanish director José Antonio Nieves Conde, whose best-known work is Surcos (1951) (Furrows), which brings Italian neo-realism to bear upon postwar Spanish society and culture, and the less auteur oriented, more market oriented, and more successful producer José Frade, who wished to cash in on the increase of interest in erotic content as seen in the lucrative “Giallo” films coming from Italy. Nieves Conde was broke and needed money, and Frade knew what was to be done: teaming up with Italian producers and enlisting a respected director who could make the most of his gorgeous “international” stars who also happened to be superb performers: Marisa Mell and Stephen Boyd (Fernández in Schneider 2013, 326-336).

My first encounter with both films was based upon old video versions with Greek subtitles uploaded to YouTube in parts. Each part had been filmed from a TV set. Though the picture quality was abysmal and the plot seemed to make little sense, it was evident to me these were well-acted, highly entertaining, and intriguing films that, for whatever reason, had never been considered for professional restoration. I was grateful to the YouTube uploader for “archiving” her video versions on YouTube, and wrote so in the comments section of her channel. Others had commented positively as well, and she offered to upload another film.

Over the course of a few months, versions of The Great Swindle were being uploaded by other YouTubers in better image quality. An Italian version (Nel buio del terrore) went up for a short time, then was probably removed through YouTube’s copyright algorithm, which tends to kick in based upon film soundtrack rights. Shortly thereafter, a higher quality version went up that had spliced together portions of the English and Spanish versions. Suddenly, the narrative of the film began to make more sense. That version was also taken down. Most recently, a mostly English version went up with an age restriction. Marta is currently not uploaded on YouTube in its entirety, as it was removed (or taken down) and has not yet been replaced. However, fan productions using scenes from the film enhanced by contemporary music soundtracks, as on the channel “alpheratz9,” or excerpts from the film framed in fan commentary, such as on the channel “adyblack,” offer viewers a good introduction to the film and why it’s worth watching—a bit like a trailer created not by a publicity department, but by impassioned audience members. And unlike full film uploads, such fan productions have the advantage that they are more likely to bypass YouTube’s copyright infringement algorithm as creative modifications of an original.

Marta is a persiflage/homage to primarily two Hollywood Hitchcock films: Psycho (1960) and Vertigo (1958) combined with the more explicit erotic touches of the “Giallo,” the Italian mystery and horror genre originating in Italy in the early sixties. One might perhaps get a sense of the combination from the following synopsis:

A lonely and emotionally unstable man lives alone in a large country mansion dedicated to the memory of his dead mother, until one day an attractive woman, Marta, arrives at his door and asks him for shelter. The young woman claims to have murdered a man in self-defense and that the police are looking for her. The man not only agrees to hide her, but also, taken by Marta’s resemblance to his wife who has also mysteriously “disappeared” years before, determines to not let her leave at any cost. In order to hide her from the police, he suggests that Marta pretend to be his wife. But as the couple lives this farce, old memories come alive and identities are confused… Both characters’ secrets are on the verge of sending them into complete psychological derangement.[i] (Fernández in Schneider 2013, 328; transl. from the Spanish by Evan Leed)

Marta has inspired several fan productions on YouTube, that are appreciative, above all, of actor Stephen Boyd’s performance. “Alpheratz9,” for example, creates a music video using scenes from Marta scored to a contemporary song entitled “Cola” by Elizabeth Grant. She highlights the scenes that emphasize the erotic elements in the film, the Giallo elements, and Boyd’s role as an “homme fatale” vis a vis Marisa Mell’s image as a “femme fatale.” It is a very well-crafted music video that is, on one level, about an individual fan’s devotion to an actor from a past era. The comments function is turned off, which suggests a closed loop between fan and actor. However, as a viewer of the video, I can share in the fan’s inner life—and appreciate the video’s artfulness—by making connections between the chosen theme music and the film images selected for the video. Comparing various versions of the uploaded film with the music video then functions to create interest in an alternative type of transnational film history: in particular, the neglected careers of Irish-American actor Stephen Boyd and his forgotten “bottom budget Spanish films,” as well as of the Austrian actress Marisa Mell (see Cushnan, Schneider and Pluhar). Significantly, the video also contains a link to the thoughtful “Stephen Boyd” fan tribute blog, where many visual materials on the Mell/Boyd team-up are much more reliably “archived” and discussed at some length. No doubt, once this film is uploaded again on YouTube in its entirety, it will be “accidentally” archived on YouTube channels that are creating sites for “forgotten” materials, such as “Giallo Realm” or “The Lost Movie Studio.”

That has already happened to The Great Swindle, where it seems that film and video editors on YouTube have taken things into their own hands and begun to create a coherent version, combining visual and audio footage from English, Spanish, and Italian copies. The icon in the right-hand corner of the most recently uploaded version reads “Iris Mediaset,” which refers to an Italian free entertainment television channel run by Italy’s largest commercial broadcaster. Here, one can imagine that there are more resources available for the complex task of turning three different video versions of an old film into one version, than there are to YouTubers working alone. But I have no doubt that the interest devoted to uploading this film and the efforts made by YouTubers to draw attention to it went into this “latest” upload, which has received over 30,000 views in the span of three months.

Unlike, Marta, which actively cites Hollywood mainstream cinema, The Great Swindle is a more “continental” European erotic crime thriller involving—to put it dryly—extremely good-looking people doing mean things to each other. I would say that The Great Swindle is very much in the (diabolical) spirit of the well-known, and multiply restored French/Italian co-production from 1969, La Piscine (The Swimming Pool), starring Alain Delon and Romy Schneider. Despite their completely contrary fates in the annals of popular European film history—one secure in the canon of popular European cinema, the other largely forgotten, there is much that is aesthetically comparable between the two films—and it isn’t just pool scenes. Both have very charismatic lead actors who had been or were in a romantic relationship with each other, which in turn was exploited for publicity purposes; both have great soundtracks, both saunter between memorable fashions and tastefully staged semi-nudity to highlight the bodies of their male and female stars. Now that the image quality of The Great Swindle is receiving greater attention the parallels are much more evident. And here too, these parallels raise intriguing questions about the history of European cinema, Hollywood’s influence as opposed to its ostensible superiority, and what was left out of the story and is now gaining an outlet via YouTube.

The impulse to “archive” media culture is strong among YouTubers, film fans, and cinema audiences. When old films such as Marta or The Great Swindle are uploaded or excerpts set to contemporary music, the labor of love involved and the effort put in are great: fans are functioning as creative and laboring producers (Stanfill 2019, 151-156; Carter 2019, 13-16), as well as archivists and even historians. So unsurprisingly, they want their uploads to stay up. But YouTube’s market driven business model has increasingly come under fire for piracy and violation of copyright. It is then, in its most recent form, that algorithms see to it that “problematic content” is removed. YouTubers have developed a number of resourceful strategies to get around the algorithm, but such strategies are no substitute for a sustainable and reliable archival function backed up by a legal framework: an archival commons to compliment the creative commons. Moreover, the work of evaluating the cultural and historical significance of content is not possible without the concept of an archive: a space where cultural artifacts are stored and organized so as to ensure the widest possible access. But as long as YouTube continues to erase creative fan labor, its archive will remain unreliable.

Recently, YouTube’s drive to create more space to upload longer content has been viewed as a threat to media artists who relied on YouTube to upload original content for which they were paid. As storage space increased, so did YouTube’s effort to fill that space with more commercially compatible content: mainstream film uploads, as opposed to alternative short videos. YouTube was in the process, critics argued, of selling out on its original mission to promote new creative video content. It’s “golden age,” according to the American technological news website The Verge, was over. It was turning into a television station (Alexander).

I would suggest that the capacity to upload longer content is a prerequisite for making the archivization of important film historical materials possible, as fans well understand, and should be encouraged and financed by YouTube in the same manner as archival collections are financed “offline.” This could include such important archival tasks as film and video restoration, as well as the support of film-historical inquiry that places newly restored materials in a broader, transnational historical context. New media models demand new models of archivization. .This is especially true in the case of the history of popular European cinema, where mainstream archiving practices are still oriented toward national (auteur) cinema histories. On a platform like YouTube, as “Eurotrash” films examined above show, alternative, transnational models are not only possible, but necessary. A popular “European” film archive made by fan collectives will make communication across languages central in terms of dubbing spoken language as well as subtitling. Comparisons between national popular cinemas will be easier, for example, in the area of content censorship as well as transatlantic casting and influences. Finally, such a “European” focus will draw attention to different fan and audience practices. The productive, inspiring nostalgia of “Eurotrash” archivists is a significant initiating step toward a conscious, audience driven archive that could be so much more than just a by-product or “accident”.

Anne-Marie Scholz currently freelances as a lecturer, writer, language teacher and translator (amscholz@uni-bremen.de). She also holds an affiliation as a “Privatdozentin” (Private lecturer) in the Dept. of English-Speaking Cultures at the University of Bremen, Germany. She has taught at the Universities of Konstanz, Bonn, Hamburg, Tübingen, Vechta and the University of California, Irvine, where she received her Ph.D. in U.S. cultural history. Her work has focused upon the transnational reception of Anglo-American popular culture in Europe as well as upon new theoretical and methodological approaches to film adaptation study. Her second book, From Fidelity to History: Film Adaptations as Cultural Events in the Twentieth Century, was published by Berghahn Books in 2013. More recently, she has published on issues of historical memory in postwar Austria as well as on the German reception of the films of Doris Day.

References

Alexander, Julia. “The Golden Age of YouTube is Over”. The Verge 05. April 2019: https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/5/18287318/ retrieved 11.07.2021.

Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2009.

Cairn, David. “Once Upon a Time in Rome”. Notebook. Mubi.com 25.07.2019.

https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/once-upon-a-time-in-rome

Carter, Oliver. Making European Cult Cinema: Fan Enterprise in an Alternative Economy. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019.

Cushnan, Joe. Stephen Boyd: From Belfast to Hollywood. FeedaRead.com Publishing, 2013.

Dyer, Richard and Ginette Vincendeau, eds. Popular European Cinema. London & New York: : Routledge, 1992. Online version.

Fernández, Javier Ludena. Entrevista por José Antonio Nieves Conde: Marta y Historia

de una traición [1999]. Anhang IX in Schneider, André, Die Feuerblume, 325-336.

Katz, Ephraim. The Film Encyclopedia: the Complete Guide to Film and the Film Industry, 6th ed., Revised by Ronald Dean Nolen. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

Pluhar, Erika. Marisa: Geschichte einer Freundschaft. Insel Verlag, 2017. [1996]

Schneider, André. Die Feuerblume: Über Marisa Mell und ihre Filme. Books on Demand, 2013.

Stanfill, Mel. Exploiting Fandom: How the Media Industry seeks to manipulate Fans. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019.

Stephen Boyd Blog: Belfast-born Hollywood and International Star from 1950s to 1970s Fan Tribute Page. https://stephenboydblog.wordpress.com/

[i] Visual examples in the form of colorful transnational film posters of Marta can be viewed on the “critcononline” bizarre film site under the category “horror” in a review of another “Giallo” film co-starring Stephen Boyd: The Devil with Seven Faces (1971).