Translated from the Spanish by Valerie Miles.

Monica thinks about her mother now as she stares at her-self in the mirror, her hand frozen midway to her face, clutching a cotton ball — isn’t she so thrilled now that she has a brand-new refrigerator, a new flat-screen TV she got for Christmas. Monica likes observing herself like this when she gets up in the morning, lingering in front of the bathroom mirror and scrutinizing herself. Sometimes she’ll go through the same routine at night, staying here like this after she fucks Rubén, watching him lying beside her, strong despite his age, compact, but with his guard completely down, vulnerable, incapable of defending himself should she wish to do something to him, Judith and Holofernes, Samson and Delilah, lose his head or lose his strength, which for all intents and purposes is one and the same thing; seeing him like that, subjugated by her, awakens a secret sense of satisfaction. She has subdued him with her strength, a superior strength because it isn’t brutal, it’s a delicate form of strength; not anything mechanical, but instead that more powerful force they call electricity, not born of muscles, but nerves. This delicate strength is what has subjugated him, drained him. She gets up, stealing across the hallway and into the kitchen where she opens the fridge to serve herself a glass of milk before reentering the room and settling back into the armchair to continue observing him, watching him sleep, his sagging, age-appropriate belly, the muscles of his legs and arms still strong and strapping, though also a bit fallen. She looks at him, contemplates him: perhaps absurdly, she feels a deep attraction to this body through which time — and life — has passed; that’s received so many releases of energy before receiving the ones she offers him. She feels admiration and desire for this man who commands dozens of others, who causes foremen and laborers to tremble like gladiators in those Roman movies, like mustachioed circus strongmen, or others who look like elegant, cultivated executives in the style of a Richard Gere, wearing fancy suits, with laptops hanging from their shoulders and cell phones pinging at all hours of the day and night. She subjugated him, she gave her body up like a narcotic and he, obedient, took it and relaxed, he went to sleep, breathing the deep breath of slumber, like that of a smoker who won’t quit, peacefully but with a hint of agitation too, all is forgotten but he’s still troubled somehow by who knows what dreams, while she sits and sips her milk daintily, skim milk, no fat, no intestinal issues please, no filling the skin cells with viscid materials. Humans are the ones who believe in miracles, not God. Who said that? She read it in some magazine somewhere, or heard someone say it on television. Rubén says it too. Monica feels the pulse of her strength, she’s her own god now, she places faith in her strength alone, her own delicate strength and the fluid electricity that runs through a clean system free of obstructions and fatty materials, connected to her spick-and-span brain, as spick-and-span as her inner thighs, which she uses to grip his head and squeezes as if to make it burst, and he moans, her nutcracker thighs, his head a mature fruit, fragile and clammy, it makes her shiver to see it there between her two velvety pincers, strength like silk, like tissue paper: the soft, silky strength of her body becomes power between the sheets, and outside the bedroom, too. You swipe a no-limit credit card at a shop in Paris and you can be sure the employee will avert his or her eyes, pretending not to have noticed and begin fussing over the jewel being placed in a silk-lined case, a jewel that adds a mere sparkle to your own polished luster, a diminutive part of you, of your personality, which expresses itself as a complex, nearly endless ensemble: a radiance that adds to the radiance of your perfectly manicured hands; of your neck garlanded by a little chain of white gold, tiny diamonds sprouting from your earlobes that the employee spies when you stand before him at the glass display cabinet. Monica catches the twinkle in his eye when he sees the little diamonds, his instantaneous appraisal of their sparkly perfection before he looks away again, as if their fire burned, the same cold fire she carries inside of her; that sparkle tells him to direct his hands and his feet only toward the vitrine where the most priceless, the most exclusive merchandise in the store can be found. The coiffure, the exclusive Armani bolero, the Vuitton bag, that’s the iridescent glimmer of her personality. She’s aware it’s not yet a matter of class, it’s a substitute for class, an announcement of its arrival, like the clarion call of a courtly procession sounding the annunciation that at the back, the end of the parade, class is advancing, refinement, it’s just waiting for the child to be born, her child will arrive with it, with class; she’ll carry it in her arms and lead him or her by the arm. It’s an inner strength, indistinguishable to almost everyone, it seeks companionship, looks for a way out of itself, encouraged by someone external, who only infrequently comes across that kind of magnetism, encouragement, complicity. When a person is in distress and doesn’t prostrate themselves or beg, it’s because they have class; when he or she wins and doesn’t hoot and laugh at everyone else, but instead keeps their gratification to themselves, behind a mask, that’s class, too. Rubén explained it that way. Not laughing when you see him flummoxed, when he doesn’t know what to do with your body because he wants all of it at the same time and in every position. When he wants to suck you here and suck you there, all at once, nibble up here and taste down there, all at the same time, and he looks at you, disoriented, and you pretend that you don’t notice his bewilderment. When despite the chemistry you notice that he simply can’t, and you realize that he’s simulating the motions of sex, he’s acting it out, don’t say a word to him, don’t allow your gaze to say, I got you now, even though sex for you at these times is like Easter to the Pope, resurrection. It’s essential to begin telling the same yearly story cycle, the same part every day. When the priest officiates Mass he repeats the same ritual every day: This is my body, this is my blood. And the faithful never tire of it, the excitement of faith courses through them every single day. For a young woman, sex is hope. It’s what allows you to begin anew next morning, as if the world had just been created. This is my body, this is my blood. The cooking classes, the hair-dresser, the mani-pedi, the beauty spa. How splendid are those signs in New York City with the word “parlor” with its nostalgia for the French “parlour”: reminiscent of that grand world of the thirties with boudoirs or powder rooms full of stuffed chairs for lounging, where you could gossip with your friend, a peroxide blond, while they touch up your makeup during the interlude of a show given by some black crooner or tap dancer. Mink coats in every sequence of the movie, a great clarity of great ideas, mink, renard bleu, not a single swoon in the dressing room, no cut-rate gewgaws, not even to take a dip in the sea: nothing on the skin but a signature bikini and emeralds or diamonds, wear only what’s a cut above — even the gangsters learned that lesson; nothing but the finest for their dolls, even if they’re floozies: it’s a lifestyle that’s vanished, which she tries to revive, a form of combat in a world that seems to have lost its moxie (as her father would say), that acts as if any old bauble is fine or even preferred over a real jewel, repudiate that world. Monica thinks back on her mother this morning while the Bertomeu family is grieving, she’d been upset with Rubén for not sharing his pain with her, but now she’s overcome with a private joy because yesterday they gave her the results of last week’s tests, and they resolve any uneasiness she might have felt. Monica thinks about what her mother will say, what her sister will say, when they find out she’s pregnant and having the baby of this terribly older man; more than anything else, though, she thinks about what Silvia and her husband will say about the news that Rubén is soon to be a father again.

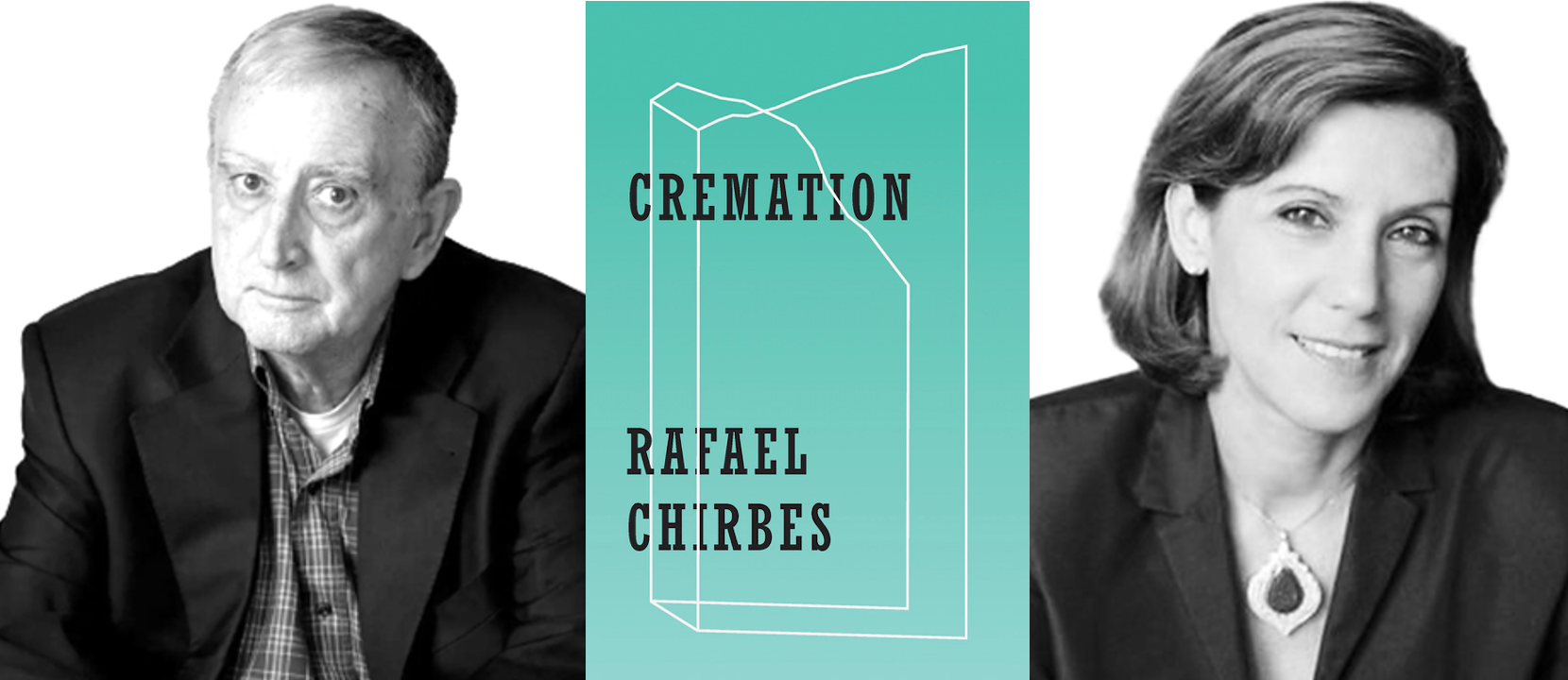

Rafael Chirbes (1949-2015) wrote nine novels and received the National Prize for Literature and the Critics Prize for On the Edge. ABC named him “the best writer of the twenty-first century in Spain.

Valerie Miles, an editor, writer, translator, and professor, is the cofounding editor of the literary journal Granta in Spanish.

This excerpt from CREMATION was published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 2007 by Rafael Chirbes. Translation copyright © 2016 by Valerie Miles.

Published on November 9, 2021