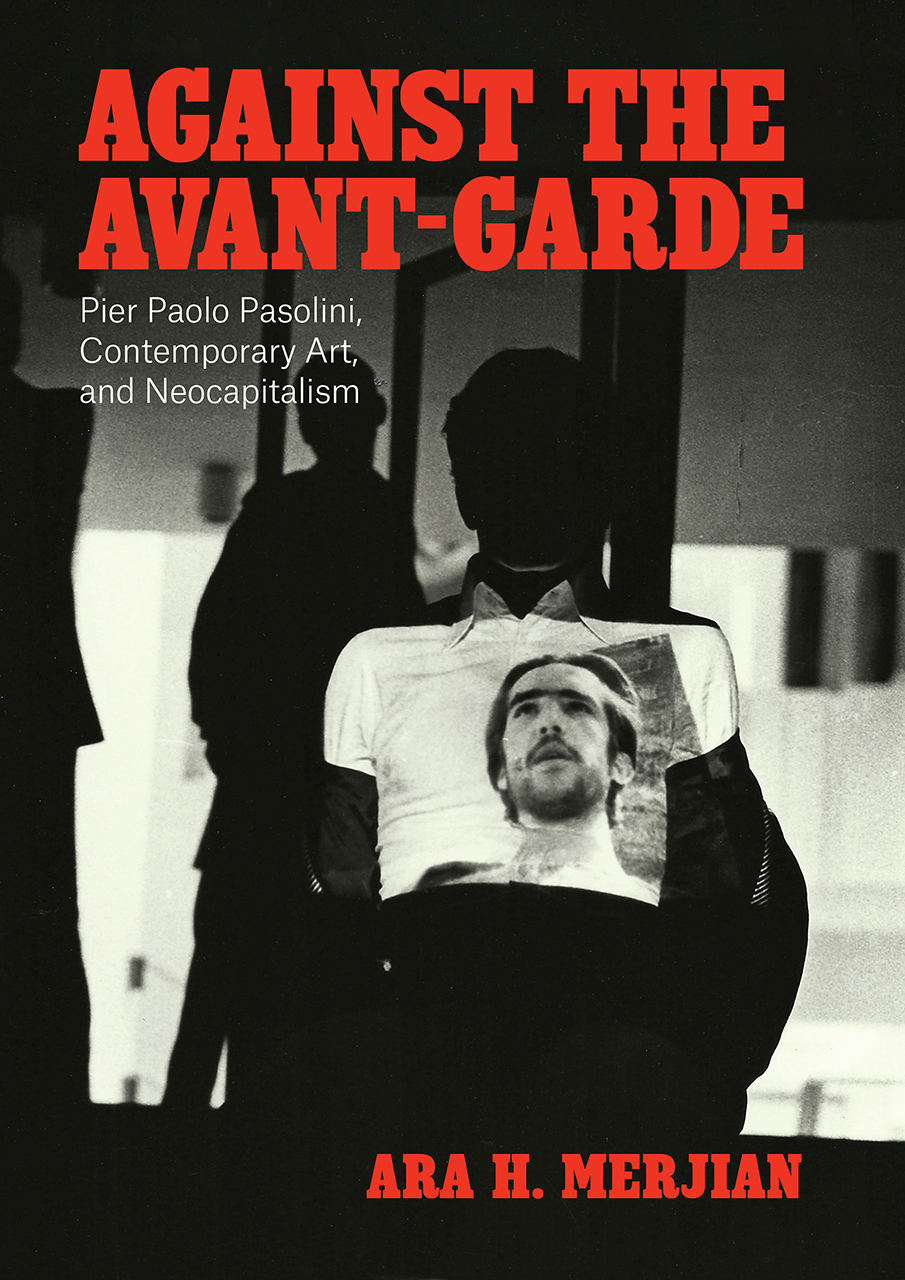

Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism by Ara H. Merjian

Pier Paolo Pasolini was the most important intellectual of twentieth-century Italy. He was the very definition, in fact, of an intellettuale—this mercurial, out of fashion concept that Antonio Gramsci, one of Pasolini’s main political and poetic inspirations, lucidly placed at the center of any effective marxist strategy for revolution. His name is so proverbial that it turned into an adjective, pasoliniano, which is used in Italian to talk about a certain militant brand of journalism, a certain licentiousness in the representation of male youth in cinema, a certain aesthetic fetishization of sub-proletarian landscapes in the outskirts of Rome. A certain way, indeed, of embodying the role of the left-wing, postwar European public intellectual.

You may recognize Pasolini’s iconic physiognomy (wavy hair and wayfarers, a white shirt) in a few scenes of HBO’s adaptations of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, briefly synthesizing, on our twenty-first-century TV screens—the whole mythology of that brand of intellectualism: a concoction of popular fame and erudition, radical politics and bourgeois affectations that few living Anglophone figures (Noam Chomsky maybe?) can sport, without irony, today. Yet, even in the role that he epitomized, Pasolini remained a living contradiction: gay but conservative, communist but nostalgic of religion, obsessed with tradition but boldly experimental. Ara Merjian’s new book helps us untangle the idiosyncrasies of this polyhedric modern monument. Casting a lucid gaze into a recent but culturally impervious past, Against the Avant-Garde conjures the complexities of Pasolini’s visual, material, and ideological context to show us how much he resisted it and how much, at the same time, he belonged to it.

The fashionable academic category of “interdisciplinarity” summarizes the nature of both Pasolini’s trans-media work and legacy, as well as the approach that Merjian (an art historian and Italianist, with a penchant for philosophy and media studies) adopted to tackle them. It is hard to place this book on the shelf (is it about European cinema? Italian art? literature? visual studies and reception? postwar ideological battles between opposing aesthetics and socioeconomic paradigms?) just as it is hard to frame its protagonist squarely in one of the many disciplines that have been interrogating his a-systematic thought and eclectic oeuvre all over the world.

Comparable to Italo Calvino in the realm of literature and Michelangelo Antonioni in that of cinema, Pasolini has been mostly studied as an acclaimed and widely impactful filmmaker and writer. However, he considered himself first and foremost a poet, and he was also a prolific polemicist and essayist, a painter, a scholar, an actor, a political agitator, a celebrity. His films and novels were met with both censorship and prizes by Catholic institutions. His poems were printed in newspapers that circulated among workers and students. His trials for indecency were as publicized as his platonic liaison with Maria Callas. His contrarian opinions on obscure questions of dialectology or the atomic bomb, on police brutality or the latest Venice Biennale, on abortion or decolonization, kept on animating the cultural debate in Italy well after his violent (and somewhat mysterious) death, a martyrdom immortalized by William Kentridge in a reverse-graffiti frieze on the banks of the Tiber. Merjian is among the few non-Italian scholars that looked at Pasolini holistically, beyond the boundaries of one medium or one perspective, mobilizing an impressive command of the rhizomatic archive that this passionate graphomaniac left behind. His goal is not to reduce Pasolini to a more comfortable definition, but to acclimate readers in the constitutively uncomfortable “scandal of self-contradiction” with which Pasolini identified.

Bookworms who obsess over the lively but ultimately marginal landscape of Italy’s underground poetry and art (such as myself) will be delighted with Merjian’s attention to Pasolini’s direct and oblique dialogue with the Neo-Avant-Garde: a diverse ecosystem of utopian left-wing intellectuals that, between the 1950s and 70s, animated Roman galleries, conferences of the Gruppo 63 in Palermo, and radical northern journals such as il verri and Officina. Some of the most unexpected visual arguments of the book are based on the covers of experimental poetry editions and magazines, visual poems, and archival photographs from happenings and ephemeral performance pieces. However, Merjian never loses himself in the meanders of Italy’s manifold postmodern anti-canon. As the table of contents readily shows, his main areas of inquiry are four of the most recognizable trends of postwar visual art, along with the literary experiments that they inspired: Abstraction, Pop, Performance, and Arte Povera. Besides the latter, so quintessentially Italian, one could say that this book uses Pasolini’s rapport with the other three movements also to de-familiarize (i.e. de-Americanize) them, and to reconsider their poetics and ideological goals beyond the dominant narrative of Anglophone histories of postwar art.

A visually fruitful, generative phenomenon that the book invariably returns on is the inconsistency between Pasolini’s proclaimed poetics, his political stands, and his own experiments with words and images. He declared that avant-garde art and literature were troublesome signs of an imminent cultural conflagration. He mocked marxist experimental writers, labeling them as unaware minstrels of Neocapitalist imperatives coming from the West. He drew parallels between abstraction and apocalypse, post-figuration and nuclear explosions, modernity itself and genocide. Yet, his films, storyboards, drawings, paintings, and literary writings often defied the same traditions that his chosen adversaries were trying to overcome—and used, in fact, similar techniques to reach similar goals. Rather than simply calling him out on an apparent aesthetic hypocrisy, Merjian embraces Pasolini’s contradictory dialectic as a creative (almost psychoanalytic) process, rooted in a sort of queer rejection of any assimilation. In doing so, he ultimately reveals that the boundaries between ideology and aesthetics, so apparently adamant on the edge of the iron curtain and in the age of the cold war, were rather porous.

Against the Avant-Garde does a wonderful job reconstructing Pasolini’s relationship with local and international pictorial and literary trends. Merjian never forgets that Pasolini was trained as an art historian himself, and studied with the greatest critic of his time, Roberto Longhi. Pasolini’s vast visual memory, after all, has been investigated by erudite iconographers, but Merjian goes beyond mere intertextuality and lets images build their own arguments and paradoxes. For instance, besides returning on some crucial echoes of classical masterpieces (from Mantegna to Pontormo) in Pasolini’s most famously iconophilic films, he finds surprising visual presences of Pop and New Dada objects in lesser known anti-modern gems such as La Terra vista dalla luna, revealing an incongruous allure for the language of comics à la Lichtenstein in the very preparatory material of the short (95-100). A particularly masterful, original, and meaningful comparison takes place on page 56, where a central scene from Pasolini’s Teorema (a film and a novel that served as a sort of socio-political manifesto) finds a perfect mirror in a classical Florentine fresco. The scene of the expulsion from Eden in Masaccio’s Brancacci Chapel seems to include a fragment of the abstract canvas produced, in Pasolini’s film, by a young character turned action-painter. The actor’s gesture of sudden awareness and existential shame, so similar to that of Adam and Eve in the fifteenth-century fresco, takes place in an uncanny aesthetic temporality that connects the prehistoric and the postmodern through a quotation from Renaissance iconography.

While overt and implicit rhymes between Pasolini’s work and coeval experimentalism are instructive and historically coherent, the most exciting sections of Against the Avant-Garde are those that explore visual and philosophical affinities between Pasolini’s aesthetics and brands of vanguardism that he was likely unaware of—or, at least, uninterested in. In particular, it is shocking to see how Pasolini elegantly fits in the broader landscape of Arte Povera, a movement that he never mentioned anywhere in his immense written production. Mobilizing the poveristi’s relations with wider postwar cultural and political phenomena, the micro-history of their critical reception and exhibitions in Italy, and the relevance of their work for current theoretical turns in the humanities, Merjian provides an entirely new angle to understand the interplay of anthropology, marxism, and phenomenology that informed some of Pasolini’s most enigmatic aesthetic preoccupations. It will be hard to discuss his adaptations of Greek tragedies or his controversial work in Africa and India without referring to the third chapter of this book (121-167), which also revisits and clarifies Pasolini’s problematic relation with the students’ movement and institutions such as the Biennale and the Italian communist party.

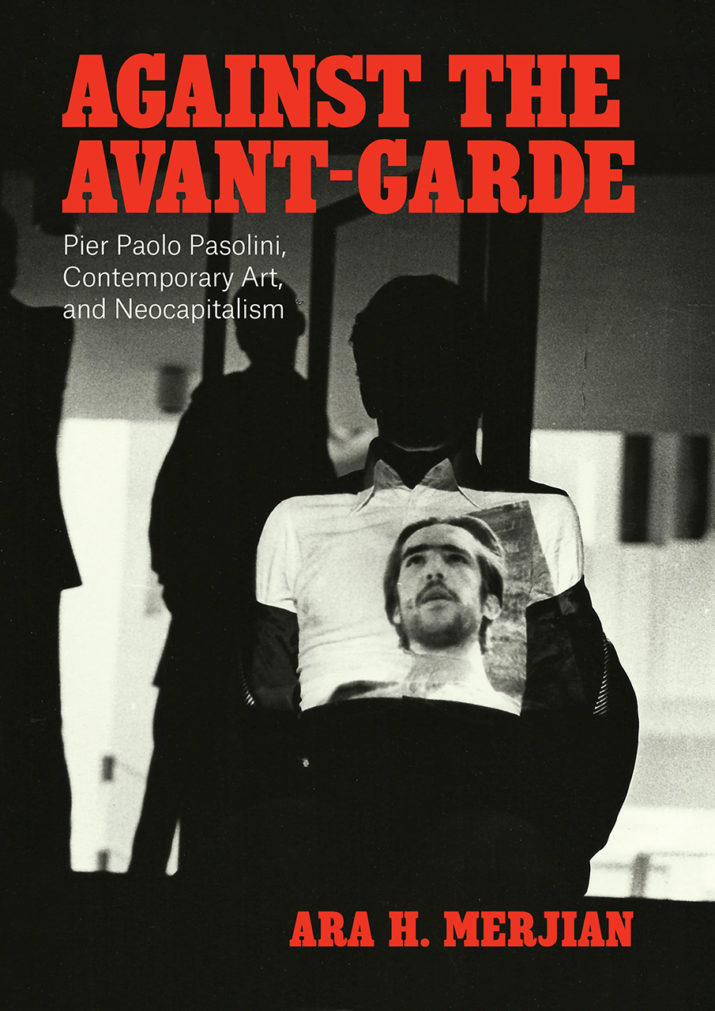

The most original contribution to what we may call “Pasolini studies” that Against the Avant-Garde proposes is probably the fourth and last chapter, devoted to Performance. It is not by chance that the publisher chose a photograph of Fabio Mauri’s performative installation Intellettuale for the cover, which shows Pasolini passively acting as a screen while a passage of his The Gospel According to Saint Matthew is projected on his white shirt. Echoing the one dimensional men of Renato Mambor’s tragically ironic Pop paintings, Pasolini becomes both a figurine and a medium in that killer shot from Bologna’s Galleria Comunale, taken just weeks before his murder. “His isolated body,” Merjian writes, “was no visual oddity by 1975. It had come to form part of Italy’s cultural furniture” (169). In this chapter, Merjian works more directly with Pasolini’s public image, resisting the paradigms of stardom studies and mere biographism, but also the pure sublimation and aestheticization (if not canonization) through which some critics, especially in Italy, monumentalized Pasolini. His body and his face are not studied in the terms of self-fashioning and popular culture, but rather as media in an organic and iconographic toolset that expands to Pasolini’s choices in casting and scene arrangement. Read through the filter of performance as both an artistic conduct and a critical theory concept, Pasolini’s work proves meaningful to understand the recrudescence of fascist strategies of bio-political spectacle and surveillance, as well as the current rapport between politics and intimacy in artistic uses of the self.

As this book shows, Pasolini’s legacy is still extremely lively and capacious. Even too capacious, since he has been evoked by different generations and on different media as a champion of either classicism or the avant-garde, progressivism and nostalgia, the queer movement and the anti-abortionist one. Merjian’s imaginative take on such an over-discussed and endlessly controversial author urges us to dismiss the reassuring glorification that many retrospectives, pop songs, artistic tributes, and films tend to offer, and to think of him as an adversary of both power and those empty forms of antagonism that he believed were destined to replace it rather than revolutionize its structures. As someone who exercised, to quote Gramsci once again, “pessimismo della ragione, ottimismo della volontà.” In the past few years, many books in various languages proposed new avenues to study Pasolini’s contradictions, but Against the Avant-Garde is the first to fully contaminate ideology with aesthetics, Pasolini’s theory with his creative practice, the historical context that he directly interacted with and the one that he needs to be placed in from a posthumous perspective. Merjian clearly engaged in a fruitful conversation with the many active scholars that, across the Atlantic, have been turning Pasolini into a trans-disciplinary topic, but he delivered a refreshingly original contribution to this intergenerational community of philologists, film critics, and historians of art, politics, sexuality, and culture.

Alessandro Giammei is an Assistant Professor of Italian Studies and Comparative Literature at Bryn Mawr College. He wrote a monograph on poet and painter Toti Scialoja (Nell’officina del nonsense di Toti Scialoja, edizioni del verri 2014) and a book of personal essays on Fitzgerald, fiction, and central New Jersey (Una serie ininterrotta di gesti riusciti, Marsilio 2018). With Chiara Valerio, he edited and translated the first Italian edition of the letters between Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey (Ti basta l’Atlantico?, nottetempo 2021). His scholarship appeared in a number of academic journals, including Modernism/modernity, Modern Language Notes, Italian Studies, and Flash Art. He regularly writes for Italian newspapers such as Domani and il manifesto. http://giammei.com

Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism

by Ara H. Merjian

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Hardcover / 304 pages / 2020

ISBN 9780226655277