New Impressions and Future Directions: Columbia University’s Collection of Ancient Western Asian Seals

This is part of our Campus Spotlight on Columbia University and the Université Paris 1, Panthéon-Sorbonne.

The modern discipline of Ancient Western Asian art and archaeology began as a colonial enterprise in the mid-nineteenth century. The European, American, and Ottoman expeditions in modern-day Iraq and Syria brought to light the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria. As a result of these excavations and the decipherment of the cuneiform script, it became clear that these early complex societies were characterized by the invention of writing, the formation of first cities with elaborate administrative structures, the establishment of religious centers, and the creation of monumental art and architecture. However, in tandem with these outstanding scholarly achievements, the history of the discipline has also been intertwined with illicit digging, looting, and trading of antiquities from the outset.

The extent of such acts has been particularly exacerbated in times of political crisis, the most recent examples of which are the two Gulf Wars and the disastrous looting of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad in April 2003, as well as the large-scale looting and destruction of archaeological sites and museums in war-torn Syria. The existing high market demand for antiquities, particularly concentrated in major European and American cities,[1] keeps feeding into this vicious circle of plunder and annihilation of the past. The 1970 UNESCO Convention on the prohibition of the illicit trafficking of antiquities had only a very limited impact on putting an end to this.

Due to their small size and high portability as well as the aesthetic appeal of their material and carving, cylinder and stamp seals have been among the most sought-after objects in both legally and illegally formed private collections. They were introduced in Ancient Western Asia during the sixth millennium BC and used to secure and authenticate goods, rooms, and documents for millennia to come. They also served as markers for individual and group identity, often acting as signatures. Additionally, particular seal stones were considered to have amuletic properties, and some of them were imported from as far as Afghanistan and India. A wide range of motifs were carved on their tiny surfaces, leaving a positive impression on soft clay when the seal was rolled or impressed. The most important difference between stamp and cylinder seals is that the latter can be rolled (rather than impressed) multiple times, enabling the user to make a continuous band of a scene, which dramatically increases the compositional potential of the medium.

When archaeological material is detached from its context through illicit digging and looting, an extraordinary amount of data pertaining to its use, function, and association to other finds, is irretrievably lost. Therefore, we will first focus on the available evidence on the provenance of this collection, then move on to the history of its use, and finally provide a brief overview of its chronological and thematic scope as well as of future plans.

The Columbia University seal collection

As the cataloguing of this vast collection is ongoing, we can only provide an approximate breakdown here. There are ca. 170 cylinder seals from ancient Mesopotamia, the majority of which can be dated to the second and first millennium BC, and ca. 25 cylinder seals from Syria and the Levant, all dated to the second millennium BC. In terms of stamp seals, the collection features thirty-four prehistoric seals, ca. 125 Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid seals, and ca. 600 Sasanian seals. Altogether, the Columbia collection houses about a thousand cylinder and stamp seals. Already Edith Porada (1912–1994), who was the Professor of Ancient Art and Archaeology from 1958 onwards at Columbia University and a leading authority on cylinder seals, provided notes in the catalogue cards referring to potential forgeries. We estimate that about 20 percent of the collection consists of forged seals. As we aim to evolve this into a study collection, both authentic and forged seals will serve as valuable training resources for detailed analysis of stone types, production sequences, and carving techniques.

Provenance[2]

In the middle of the twentieth century, Columbia University had planned to build a museum on campus. Although the museum was never constructed, various donors and collectors made contributions of art to fill its galleries. These objects, including the ancient cylinder and stamp seals, now form the university’s art collection which is under the stewardship of Art Properties. Arthur Sackler was a major patron of the proposed museum. During the 1960s, he established a gift fund which allowed the university to acquire art on his behalf. This fund was used to purchase the seals from private collectors and art dealers, most of whom also sold or donated objects to other institutions in New York City and on the East Coast. Edith Porada was heavily involved in this process. She communicated with collectors and dealers, appraised the material they were offering, and facilitated their payments.

Six transactions took place between the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1967, Edith Aggiman and Adrienne Minassian sold seals from their collections to Columbia. Aggiman sold and donated other Western Asian artifacts from her and her husband’s collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) that same year. Upon her death several objects were bequeathed to the MET in 1982. These items were diverse, but a few seals and cuneiform tablets were included. Adrienne Minassian and her father were dealers of Western Asian and Islamic antiquities. They each amassed and sustained their own personal collections. In addition to the seals Adrienne Minassian sold to Columbia University, other museums, such as the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, purchased objects from her. She also donated and bequeathed artifacts and Qur’anic manuscripts to the MET, Freer Gallery of Art, and Brown University.

In 1968, the Sackler gift fund was used to acquire seals from Joel L. Malter, an antiquities dealer based in Encino, California, who also donated seals to museums in New York. One of these donations occurred in 1976 when he donated a cylinder seal to the Brooklyn Museum. In addition, the MET purchased stamp seals from Malter in 1978. Then in 1969, Dr. Leonard Gorelick, a dentist, was paid for his contribution of seals to Columbia University. From 1975 to 1976, Gorelick’s personal collection of cylinder and stamp seals was exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum. Later he donated seals to the MET. Gorelick had a keen intellectual interest in these artifacts. He not only collected seals but he also studied them extensively, publishing articles on their manufacture and the use of dental technology to examine them (Gorelick 1975).

The final two acquisitions took place in 1971 when seals were purchased from Feridun Demokan and Habib Anavian. Demokan first showed his collection to Porada in 1961, but at the time she did not have the financial means to secure them (The Edith Porada Papers [EPP], Box 1C, Folder Coll & Mus. Demokan, I). When she contacted him in 1970, however, the Sackler gift fund had been established and was utilized regularly. Based locally in New York, Habib Anavian co-owned a collection of Western Asian antiquities with Nuri Farhadi. Along with cylinder and stamp seals, Farhadi and Anavian Co. sold Iranian ceramic vessels and metal bridle ornaments to the university in separate transactions during the 1960s and 70s. Similar to the dealers and collectors previously discussed, the MET and the Freer Gallery of Art possess items that were once part of Farhadi and Anavian’s collection.

Due to the 1970 UNESCO Convention, the date of these last two transactions may provoke some apprehension. With regard to these acquisitions, it is necessary to note that the convention did not enter into force until 1972. Even so this fact does not mean that before 1972 all artifacts were legally excavated and exported. The activities of looters, dealers, and collectors could have violated a source country’s national legislation regulating the movement of tangible cultural heritage prior to the international convention. One example of these national legal measures that regulated the movement of cultural objects is Iraq’s Antiquities Law No. 59 of 1936. With very few exceptions, Article 26 prohibited the removal of antiquities from Iraq. Furthermore, the exploitation of cultural artifacts was not necessarily just or acceptable if a country did not have a robust domestic legislation addressing cultural property in place before 1970.

Again, the archives documenting the university’s collection do not reveal how these dealers operated or from whom collectors purchased their seals. The process could have been entirely legal, or problematic tactics could have been used. Buyers may have been aware of destructive activities such as looting and illicit trafficking. Malter for instance, consciously purchased stolen and illicitly trafficked antiquities from Turkey in the late 1990s (Colker 2000). Hence it is uncertain whether the seals were acquired through legal and ethical means before they were purchased by the university.

History of the collection’s use

Edith Porada herself studied the seals extensively. Having consulted the now defunct Sackler Labs formerly located in Low Library, she had a scientific analysis conducted on some of the seals. By using X-ray diffraction, scientists at the labs identified the type of stones utilized to carve the seals (EPP, Columbia Box 18, Folder 20). Porada also created drawings, photographs, and impressions. She included an image of a seal impression from our collection in her publication on Elamite art and archaeology (Porada 1971, fig. 10; see also Porada 1964).[3] The resources she made are still kept in Art Properties and they constitute one of her most important and lasting contributions to the collection. These materials were instrumental for the renewed efforts to study and catalog the seals.

Furthermore, Porada intended for the seals to be a teaching resource, providing students with opportunities to conduct hands-on research. Various students wrote catalog cards and photographed the seals. After the collection fell into disuse, Porada formed a class in 1988 called “Survey of Ancient Near Eastern Seals: Preparation for an Exhibition” to re-engage students on the topic (EPP, Box 5, Folder Sackler Exhibition). At the time, the curator of Art Properties, Sarah Weiner, wanted to exhibit the seals and related artifacts in a public setting. Students participated in this project by drafting catalog entries and exhibition labels for objects. They were required to write essays on the cultural and historical context of these items. Porada planned to name the exhibition “Ancient Near Eastern Life in Ancient Near Eastern Art.” Unfortunately, there is no record of the exhibition itself and it is not clear if the seals were ever displayed within the Columbia University community. However, true to Porada’s intentions the collection still has the potential to be a vital teaching resource within the university for the study of ancient seals.

Chronological and thematic scope

Third millennium BC

One of the earliest seals in the collection, dated to the Third Dynasty of Ur (The Ur III Period, ca. 2112–2004 BC), is most likely carved from chlorite, a commonly used soft stone imported from sources in Iran or Oman (Fig. 1).[4] It features a “presentation scene,” which entered the iconographical repertoire of Mesopotamian seals in the preceding Akkadian era (ca. 2334–2154 BC) but became particularly popular in this period (see Collon 1982). A presentation scene of this time typically involves a worshipper depicted to the far left of the impression, who is led by the hand by a goddess and presented to a seated deity or a deified ruler. Despite the worn-out surface of this particular seal, it is clear from both the seal stone and the impression that the badly-preserved cuneiform inscription, the legible signs of which give the owner’s patronymic (familial affiliation), was added at a later date. Seals were highly prized possessions in antiquity and were passed down as heirlooms and reused over generations, with or without being recut. Sometimes the inscriptions were left intact despite change of ownership in order to emphasize familial, social, or political continuity, other times the imagery and text were modified considerably according to the needs of altering social and administrative contexts. Therefore, rather than diminishing the authenticity of seals, ancient recutting often rendered them more appealing (Smith 2012).

However, the exact relationship of the recut inscription to the “presentation scene” depicted on our seal was not possible to ascertain due to the uneven surface of the badly-executed impression possibly made in the 1970s. Our new impression, the photograph of which was further processed here (Fig. 1), made it clear that the worshipper was originally followed by another deity. Under the frame of the added inscription, this deity’s head with a horned crown as well as traces of her raised arms and long striped robe, in line with the convention of the time, are still visible.

Fig. 1. Suppliant goddess leading a worshipper toward an enthroned deity, Third Dynasty of Ur, c. 2112–2004 BC. Chlorite (?), 37.4 mm x 16.8 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S3836.016). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

Second millennium BC

Scenes of kings with maces approaching suppliant goddesses were standard of cylinder seals created during the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1894–1595 BC). The collection includes several of these seals, as well as one with a variation on the theme where the king stands before a nude frontal female figure (Fig. 2). Such figures were depicted on terracotta plaques excavated from Iraq and may have been considered powerful, protective images. In this particular image, the scene lacks the smaller motifs that are often carved between and around the two main iconographic elements on seals with this type of theme.

Fig. 2. King approaching a nude female figure, Old Babylonian, c. 1894–1595 BC. Haematite, 19.3 mm x 10.4 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S4447.001). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

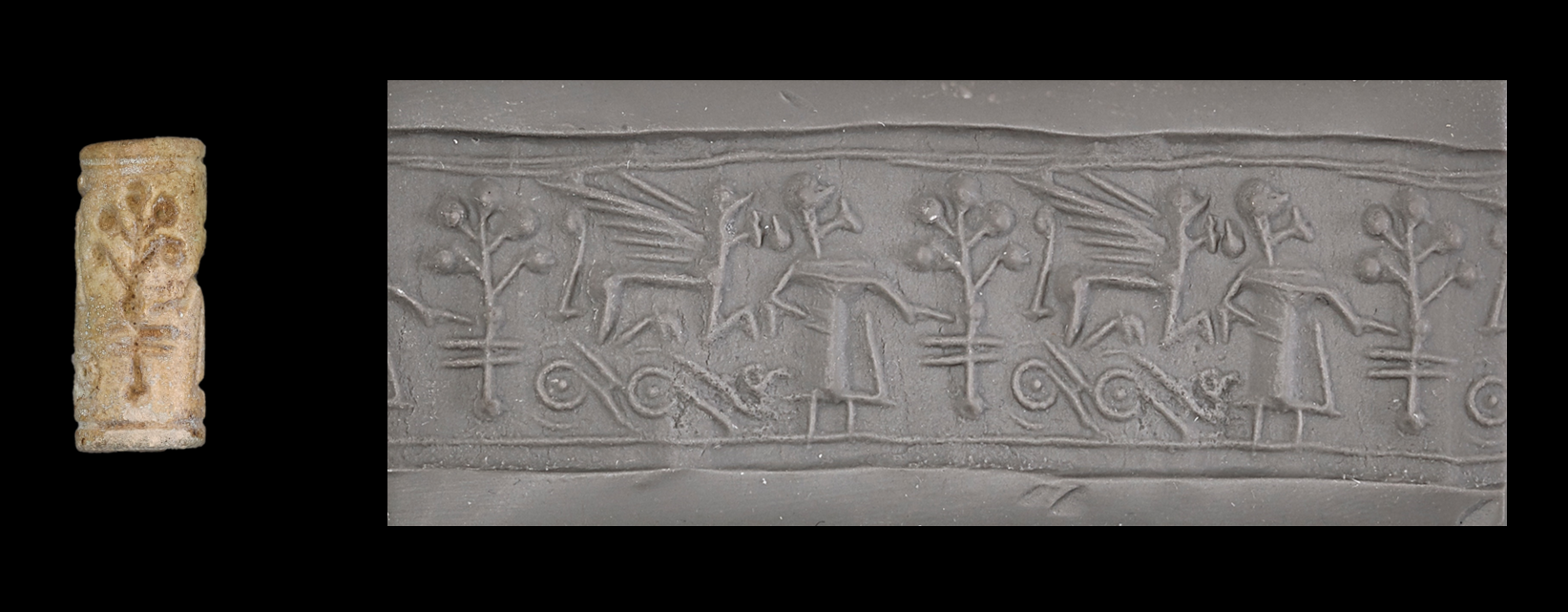

Mitannian seals in Columbia’s collection exhibit seal carving traditions of northern Mesopotamia in the mid-second millennium (c. 1500–1300 BC). Deeply carved onto this frit seal is a figure tending to a tree and a sphinx above a guilloche (Fig. 3). A drill was used to render the ends of the tree and this technique, along with the iconography, are characteristic of Mitannian common style seals. This subgroup is one of two distinct styles in Mitannian seal carving.

Fig. 3. Human figure attending to a tree, Mitannian, c. 1500–1300 BC. Frit, 26 mm x 11 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S3836.039). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

First millennium BC

Fig. 4. Two figures driving a chariot, Neo-Assyrian, c. 1000–612 BC. Limestone (?), 22.6 mm x 7.8 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S3836.051). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

In terms of the first millennium BC, a Neo-Assyrian seal in our collection demonstrates vividly the compositional potential of the medium (Fig. 4). Here, two charioteers are shown in motion. They are participating in a hunt and accompanied by a dog depicted on the foreground. Hunting scenes are known from multiple media in this period, including the famous palace reliefs from Kalhu (Nimrud) and Nineveh. However, the main difference here is that certain cylinder seals can disrupt the well-known divide postulated by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781) between visual arts and literature: While the former is able to represent “bodies” simultaneously in space, the latter can only represent “action” successively in time. A cylinder seal has the potential to do both, since this chariot scene “unfolds” in time as the seal is rolled in space: Two riders in a lone chariot turn into energetic participants in an extensive hunting campaign.

Fig. 5. King arresting animals, Achaemenid, c. 550–331 BC. Translucent red material with pitted surface, 25.9 mm x 10.2 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S4447.004). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

From the Achaemenid Persian Period (559–331 BC), our collection features a well-preserved cylinder seal with the “master of animals” motif (Fig. 5). This is one of the most popular themes in the glyptic of this period and involves a standing male figure extending his arms to either side of his body to hold and arrest animals or hybrid creatures (Garrison and Root 2001). The animals shown on this seal are a lion and a goat, both depicted rampant. A date palm tree in the field accompanies this trio. Such heroic encounters, often associated with kingship, were not only symbolic representations of human domination of the natural order, but were also visually appealing due to their central, symmetrical verticality, lending itself well to heraldic compositions.

First millennium AD

By far the largest component of our collection is an assemblage of over 600 stamp seals. Most of these artifacts date to the beginning of the first millennium AD when Central and Western Asia were ruled by the imperial Sassanian dynasty (ca. 224–631 AD). The images carved onto the flat surface of the seals include portraits, fire altars, and a range of flora and fauna. From a single stem tied with a ribbon, three tulips branch outwards on this stamp seal (Fig. 6). Tulips could have possibly been associated with Zoroastrianism or carved here for their aesthetic beauty (Brunner 1979), but the precise reasoning for the use of the motif on stamp seals remains obscure.

Fig. 6. Tulips, Sassanian, c. 224–631 AD. Burnt chalcedony, 16.6 mm x 19.6 mm. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, Arthur M. Sackler Collections (S3837.046). Photographed by Dwight Primiano, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library.

The next step is to complete the cataloguing of this extensive collection, which will then be made available through a digital database, accessible via Columbia University Libraries (CLIO). Although some progress has been made on this task, it is clear that a more extensive research project is needed to thoroughly catalogue the entire collection. Another objective is to choose a subset of the collection with a number of representative authentic and forged seals, and to organize them into a study collection that can be utilized for hands-on training by students at Columbia and in New York.

In tandem with these tasks, more work has to be done to collect as much provenance-related information as possible, ranging from deepening research into the New York-based dealers that we have already identified, to tracing their contacts in the source countries. Any future work on this collection has to critically engage with both its acquisition history as well as the colonialist vestiges of our discipline.

Majdolene Dajani earned her MA in Art History and Archaeology from Columbia University. She is a research associate and cataloger at the Morgan Library & Museum. Her research focuses on the reuse of ancient iconography and she was awarded a fellowship by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to study the longevity of patterns in Levantine decorative arts.

Erhan Tamur is a PhD candidate at Columbia University and a curatorial research associate at the Morgan Library & Museum. He has worked and published on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art historical theory, style and ethnicity, and the politics of archaeology. His dissertation, entitled “Site-Worlds: An Account of Material Lives from Tello (ancient Girsu),” brings the art history of a Sumerian site from the third millennium BC into the present and is supported by a two-year fellowship from the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA) of the National Gallery of Art.

We would like to thank Roberto Ferrari, Lillian Vargas, and Eric Reisenger from the Art Properties for their kindness and support. Alexis Hagadorn and Emily Lynch from the Columbia University Libraries Conservation Program carried out the microscopic cleaning of the seals and provided us with space to make new impressions. Dwight Primiano took the photographs of the seal stones and new impressions, which were further edited by the authors. Our sincere thanks are also due to Sidney Babcock, Zainab Bahrani, Sarah Elliston Weiner, and Trudy Kawami who kindly shared with us their knowledge of the history of the collection. Last but not least, we would like to thank Holger Klein and Alain Duplouy for creating us the opportunity to conduct research on this collection within the context of the Parallel Heritages Project.

References

[1] While the European and American centers kept their importance, the antiquities market has increasingly been centered in Asia and the Gulf States in the last decades.

[2] All of the information regarding the transactions mentioned in this section are based on the archival documents housed at Art Properties, Columbia University.

[3] In her 1964 publication, Porada refers to two seals in the Columbia Libraries. It is uncertain if these objects are part of Art Properties’ collection or a different one on campus as the article was published three years before the collection was established. Furthermore, one of the seals Porada discussed was donated by Dr. Dallas Pratt and Mr. Aubrey Cartwright, who are not mentioned in the paperwork relating to the seals housed in Art Properties. Currently, the location of these two seals is unknown.

[4] As this stone is often confused with steatite and serpentine, its exact identification requires laboratory analysis.

Brunner, Christopher. 1979. “Sasanian Seals in the Moore Collection: Motive and Meaning in Some Popular Subjects.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 14: 33–50.

Colker, David. 2000. “Dealer Pleads Guilty to Selling Stolen Relics.” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 2000.

Collon, Dominique. 1982. Catalogue of the Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum. Cylinder Seals II: Akkadian, Post-Akkadian, Ur III Periods. London: The Trustees of the British Museum.

Garrison, Mark B. and Margaret C. Root. 2001. Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets. Volume I: Images of Heroic Encounter. Chicago: The University of Chicago.

Gorelick, Leonard. 1975. “Near Eastern Cylinder Seals Studied with Dental Radiography.” Dental Radiography and Photography 48, no. 1: 17–21.

Porada, Edith. 1964. “The Oldest Inscribed Works of Art in the Columbia Collections.” Columbia University Library Columns XIII: 25–33. Reprinted in Edith Porada zum 100. Geburtstag, edited by Erika Bleibtreu and Hans Ulrich Steymans (Fribourg, 2014), 151–154.

Porada, Edith. 1971. “Aspects of Elamite Art and Archaeology.” Expedition 13, no. 3 (Spring): 28–34.

Smith, Joanna S. 2012. “Layered Images and the Contributions of Recycling to Histories of Art.” In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 12–16 April 2010, London, Vol. 1, edited by Roger Matthews and John Curtis, 199–215. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

The Edith Porada Papers, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Published on May 11, 2021.