Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan.

1. Short the Suffering

Concrete’s no job for sissies.

Maybe that’s why our father decided, soon as we were old enough, my little sis and I, to educate us in cement, concrete, and casing.

You could sorta say, thanks to our precocious edu-cation, that my little sis fell into concrete as a young girl. Sorta.

For you to understand concrete, I’d have to explain an infinite number of things. I’d really have to get myself together. And I’d have to begin.

I’d have to.

But where to start? The end? The beginning? The middle?

And where is the middle, anyway?

In shit, there’s no middle. There’s just shit. Shit’s the milieu . . . In concrete, it’s the same.

So may swell begin at the beginning.

I have to tell you, then, that my little sis and I poured our first concrete in very remote times, still-primitive times. We did it by hand. As in, with a shovel. It was before our mother gave my little sis, our father, and me a concrete mixer. It was for his birthday, but it was a pres-ent for us, too.

A red concrete mixer with a 2-HP electric motor.

It changed our lives. It muddernized us. We started working on big projects with our father on an industrial scale. We’d concrete every weekend in the countryside, even some of summer vacation too. Every time we drove to town for groceries, our father would say, coming out of the butcher’s, for example: “How ’bout we go grab a bag of cement next door?” My little sis never said no. Our mother said noth-ing. (I never had a say.) I also have to explain, so you don’t misinterpret my mother’s silence, that concrete, lime, cement, mortar, hybrid or not, with or without a mixer, is awfully messy work. Our mother wanted to keep us clean, even on the weekend. That was the rule. So there were endless loads of laundry, big ones. So many loads and so much mess that the washing machine couldn’t take it anymore. Our father had a theory. Those machines have weak innards. They’re not designed to guzzle so much cement and gravel. They’re not concrete mixers. Though in theory, a concrete mixer and a washing machine work the same. But ingesting all that muck was like gulping down fatty food that turns into pipe-hardening choles-terol, or stones in the urethra. The machine guzzles, chokes, then flocculates and coagulates. The drain stops working, the guts clog. And then bam! Infarction, ictus, and splosive diarrhea.

At night in our room when we went to bed, my little sis, who’d spent an entire laundry cycle feeling up the machine and listening to the sounds of its insides, con-firmed the diagnosis. It’s like when you have a stomach-ache. The machine gurgles, hiccups, or worse, and then makes a ghastly effort to empty its guts out one end or the other.

I wondered if the machine was suffering, if it wasn’t cruel to make it keep choking our laundry down.

But whether spunky or sick, it was clear that it no longer met our housekeeping needs.

The dirty laundry kept piling up. Our mother was losing all hope of keeping us clean. She and Grandma polished us from top to bottom, morning, noon and night. But the Portland would bind with the sweat, the rain, the hose’s excretions. We were ashen. We shed spalls into our soup. The made-in-France natural boar bristles clothes brush no longer sufficed.

Our grandma switched to a wire brush.

And then we’d come back all plastered after a session with the concrete mixer, and she’d have to work her fingers to the bone again to deplaster us with her poor primitive methods.

One day, at lunch, watching us shed lumps into the grated Gruyère, our mother threw the brush into our father’s noodles and started to cry into her own.

Our father needed things explained. How the boar bristles brush worked, and the wire brush. The reason for its sudden appearance in his noodles. I couldn’t do it, my throat was in a knot just seeing our mother salting her noodles with her tears.

Total bewilderment.

In such cases, my little sis is the one who comes to the rescue. Little sis is no sissy, you see. Quite the oppo-site. Bewilderment? She spits on it. The bewildered? Pansies and pussies. They enrage her. She reviles them, big time.

Insults like that motivate the bewildered. They snap back to life.

As for our father, it galvanizes him, even.

He said all the machine needed was a simple triple bypass. I open it, I dismantle it. I brush the filter vigor-ously, give the ducts a good sweep. I change the pump . . . I have an old one saved up that’s like new. I cut a piece of the garden hose . . . it’s long, there’s plenty. I tighten the clamps, fit the sheet metal back on. I put the whole thing back together and it’s good as gold.

Since the noodles had gotten cold after so much bewilderment, and were too salty even before our mother had cried all over them, we began the operation without delay.

We assisted our father.

He felt it was important to teach us, to demon-strate things. He’s always loved to pontificate. To wax and buff philosophical, too, sometimes, and intrepidly. But mostly to give orders.

He’s a leader and a pontiff.

Leader, pontiff, sure, but pedagogue, never. That’s a bad word, a suspect word, a word that stinks of tearooms.

What tearooms? And what do tearooms have to do with our training? And how many cups of tea does it take to be able to profess and wax and boof?

We don’t know, and he won’t say.

A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enema.

The bypass, in any event, was an opportunity to pontificate. Later in life, whenever we were thrown a curveball, it came in handsy, all that waxing and buff-ing and all that polished pontification. You can’t count on repairmen, all they do is tell you your machine, that one there, it’s fucked and you gotta buy a new one. You don’t say! They take their customers for chumps. Often, they’re not wrong.

We followed orders. We brought our father the tools per the necessities of the operation. We held the flash-light so he could see the failing organs he was hunched over. We set aside the bits of entrails he handed to us over the course of the dissection. In our pockets we stockpiled the little screws, the little joints, the teensy nuts and bolts, those itsy-bitsy things that are easy to lose and then later you find yourself up shit ’crete.

We were learning new vocabulary, all the technical terms of the trade: bitch, crescent wench, o-ring, cotter pin, a pox on your house, hex driver, piece of shit, sleeve clamp, and go fuck yourself!

When it was over and we’d de-poxed, re-erected, taptaptapped, and butted and plugged everything, he said, Let’s test this bitch.

And into the drum he shoved all our rags, stiff with cement.

Often, there were leaks. Our father called them incidental leaks, collateral leaks, even. They tended to intensify. According to my little sis’s calculations, the volume of the incidental drainage rapidly approached that of the nominal drainage. The laundry room turned swampy.

I have to explain one thing: this was before we decided to lay in a concrete floor like you might’ve seen in a Jerry bunker. Cause before, in primitive times, before we really radically muddernized, the laundry room floor—which used to be, in more ancestral times, possibly even prehistoric times, a henhouse—its floor, before the Teutonic slab and muddernity, was a dirt floor.

Hens the swamp.

Hens the stagnation and the unexpected humid-ity that rusted the sides of the bitch, specially where our father whacked it with his hammer to put it back together after its open-heart surgery.

Hens the laundry, waiting to be washed or freshly cleaned, spilling directly into the sludge. Which was bad news for the machine’s bowels.

Hens the sighs of our poor little mother whom our father forbade to do the laundry without her boots on. OD green rubber boots, which we’d given her specially for her birthday and for the laundry room.

It wasn’t so much the sludge that my father was worried about. Detergent, cement, and bleach by the glassful to top it all off, that’ll kill the bacteria, guaran-teed. The soapy, caustic mud wasn’t much of a concern. The lack of electrical insulation, on the other hand . . .

The lack of electrical insulation scared us. All the more so since in those ancient times, you have to under-stand that our electrical setup was also primitive. We had demonstrable proof. In fact, we were reminded of it every day.

For example, we used to have a nice wood-burning stove, with iron cabriole legs. Louis XV-style. This stove did it all: cooking, hot water, heat. But, electrical every-thing! That was the muddern mantra. So we chucked the wood-burning stove, and our father replaced it with an electric range. When you turn on the oven, the cir-cuit overloads, the breakers go snap! poof! It’s simple, our father explained to Grandma, when you want to use the oven, just unplug the fridge and it won’t fry the fuses anymore.

Often, by the end of summer vacation, after so many tripped circuit breakers, we didn’t have any fuses left. So we boiled water for coffee with the help of a blowtorch.

But the worst was the lamps.

Our father doesn’t like waste. He repairs things with old recycled wire. The cables get shorter. The lamps in the house give us a shock every time we try to turn them on. We don’t dare touch them anymore. We’re like rats in a lab experiment. We’d rather stay in the dark and wait for someone else to sacrifice them-selves, resign themselves to getting electrifried for the common good.

I’m getting a bit sidetracked with these electri-cal deviations (but not smuch as all that: everything is connected, this is a serious web I’m tangled up in), a bit derailed from our original affair—the story of the concrete.

So, to recap: the concrete mixer was suffering, the washing machine was suffering, our mother was suffering.

My little sis pointed this out to our father with great tact and composure. And as soon as he was good and bewildered, she insulted him BIG TIME. There was nothing he could do but take the matter to heart and, pronto, by the horns.

We had to short the suffering immediately.

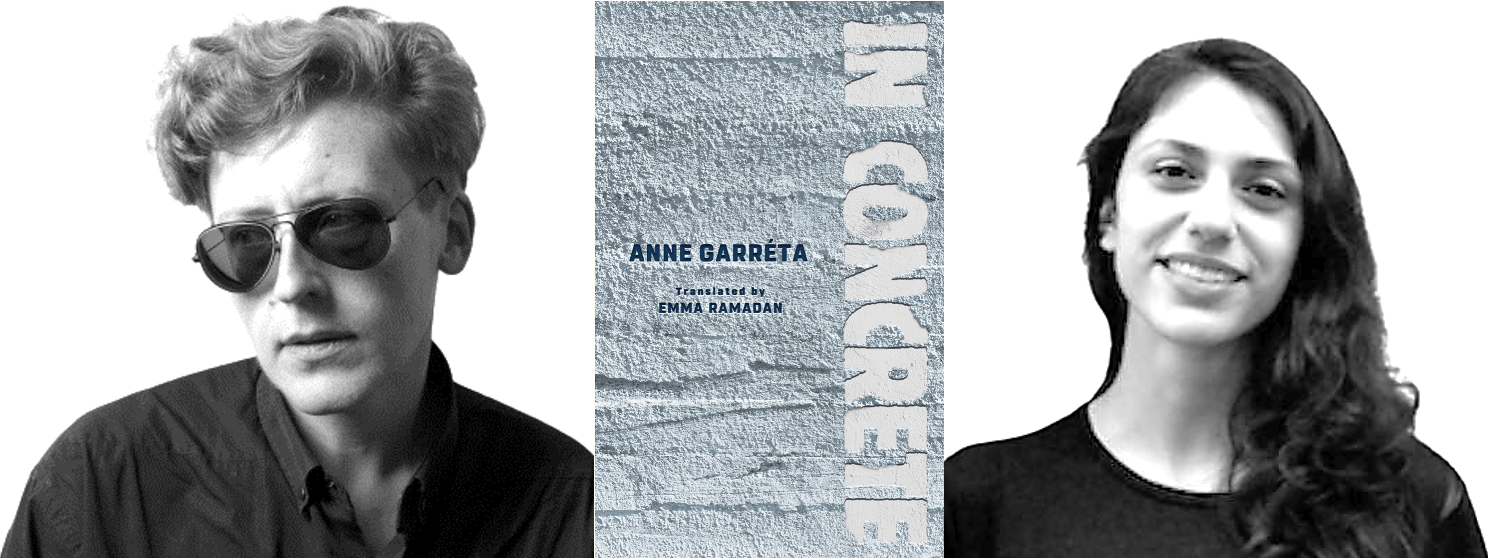

Anne F. Garréta is a graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, received her License de Lettres at the Université Paris 4 (Sorbonne), her Maitrise and her D.E.A at the Université Paris 7 (Diderot), and a PhD at New York University. The author of six novels, Garréta was coopted to the Oulipo in 2000. Her first novel, Sphinx (1986), which caused a sensation when Deep Vellum published its first English translation in 2015, tells a love story between two people without giving any indication of grammatical gender for the narrator or their lover. She won France’s prestigious Prix Médicis in 2002 and the Albertine Prize in 2018 for her book, Not One Day, which was also nominated for a Lambda Literary Award. Garréta teaches regularly in France at the Université Rennes 2, and more recently at Paris 7 (Diderot), and is a professor at Duke University.

Emma Ramadan is a literary translator of poetry and prose from France, the Middle East, and North Africa. She is the recipient of a Fulbright, an NEA Translation Fellowship, a PEN/Heim grant, and the 2018 Albertine Prize. Her translations for Deep Vellum include Anne Garréta’s Sphinx and Not One Day, Fouad Laroui’s The Curious Case of Dassoukine’s Trousers, and Brice Matthieussent’s Revenge of the Translator. She is based in Providence, RI, where she co-owns Riffraff bookstore and bar.

This excerpt from IN CONCRETE was published by permission of Deep Vellum Publishing. Copyright Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, © 2017. Translation copyright 2021 by Emma Ramadan.