Translated from the Russian by Sasha Dugdale.

4. Sex and the Dead

I must have been about twelve. I was hunting around for some-thing interesting to look at. There was plenty of interesting stuff: with every death a pile of new objects appeared in our apartment, deposited just as they were, trapped in a sudden end state, because their previous owner, the only person who could have freed them, was no longer among the living. The contents of Grandmother’s last handbag, her bookshelves, buttons in a box, everything had simply stopped, like a clock, on a particular hour of a particular day. So many objects like this in our house. And then one day I found an old leather wallet in a far drawer. It contained a single photograph.

I could see right away what sort of a picture it was. Not a pic-ture, or a postcard or, say, a picture calendar. A naked woman lay on a divan, looking at the camera. It was an amateur shot, taken long ago, already yellowing with age, but the feelings it aroused in me were utterly unlike the way great-grandmother’s Paris let-ters or grandfather’s jokey poems had made me feel. This picture added nothing to the throat-tightening feeling of family collec-tivity, to the black-and-white many-headed chorus of unknown relatives, always happening just behind my back, or to the hunger I felt when I saw something unknown and foreign: The prom-enade at Nice by night, on a prerevolutionary postcard. There was something clearly illicit about the photograph, although that could hardly have bothered me, quietly avoiding my parents, and on my own private search for the forbidden. There was a faint licentiousness in it, too, although the woman’s nakedness was open, straightforward, and full to the camera. Strangest of all, the photograph had no relationship to me at all. It belonged to someone else. The fact that the wallet had lost its owner long before did not change this feeling of strangeness.

The woman lying on the leather sofa was not beautiful. My sense of aesthetics had been formed by the cast gallery in the Pushkin Museum and a book on ancient Greek myth, I was af-fronted by her many bodily defects. Her legs were shorter than they were supposed to be and her breasts smaller, but her bottom was much larger and her tummy pudgy in a way that was very unlike marble. All these defects made her look lively, as anything living in ignorance of perfection looks lively. She was grown-up, in her thirties, as I now realize, and not a “nude,” simply a com-pletely naked woman, although that wasn’t the most striking thing. The woman was looking straight at the viewer — that is, at the camera, that is, at me. Her stare had such intensity: it was utterly unlike the radiantly unfocused gaze of a goddess, or a model in an artist’s studio.

Her gaze had a very direct purpose to it: between the woman and her witness something was happening, or was going to hap-pen. Strictly speaking, her stare was already that happening: it was the conduit or the corridor; the black hole. Her face was wide, flat, with slits for eyes, and there was nothing else in it apart from the intensity of the stare. Her communication was intended for the bearer of the photo, but I had somehow taken his place, and this made the situation both tragic and absurd. It was so very obvious that The Lady On The Leather Sofa (unlike the whole of art and the whole of history, which was definitely intended for me and took me into account) didn’t have me in mind as a viewer, didn’t want me, and I knew with certainty that someone else should have been in my place, someone with a name and a surname, and possibly even a mustache.

The absence of this other viewer made the whole thing feel indecent, coitus interruptus in its most basic sense, and I was the one interrupting. I’d turned up at the wrong time, and in the wrong place, and I’d witnessed what I shouldn’t have witnessed: sex. The sex was not in the body or the pose, or even the surround-ings (although I remember them well) — it was in the directness of the gaze, its lack of ambiguity, the way it paid no attention to anything beyond the scene. Strange when you think that even thirty years ago both participants were probably dead and most certainly are now. They have died and left the sex act orphaned in an empty room.

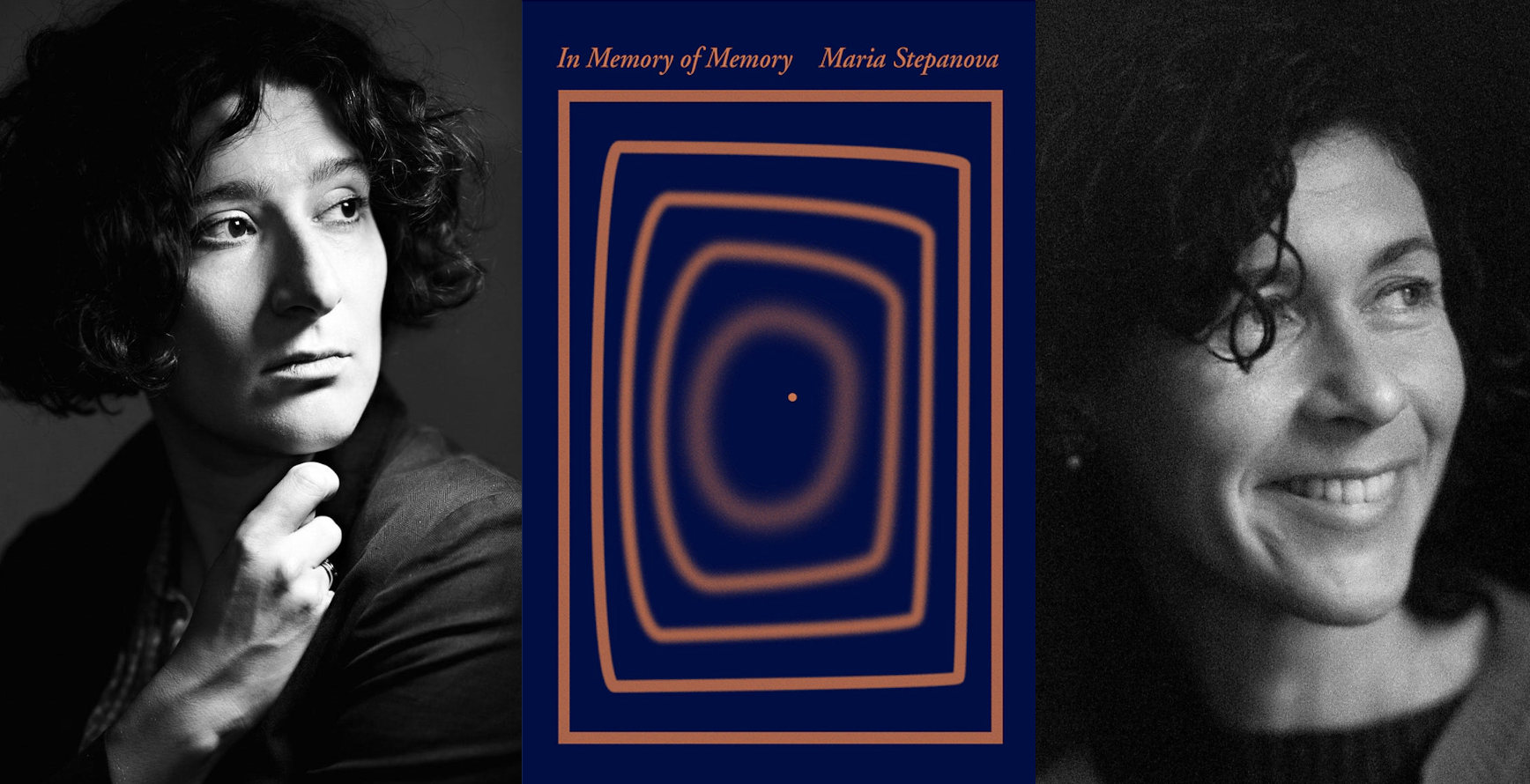

Maria Stepanova, born in Moscow in 1972, is a poet, essayist, and journalist, and editor in chief of the online newspaper Colta. In 2018, she was awarded the Bolshaya Kniga Award for In Memory of Memory.

Sasha Dugdale is a poet and translator. She has published five collections of poetry with Carcanet (UK), the most recent, Deformations, is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize. She is a translator of Russian drama and poetry, including work by Elena Shvarts, Maria Stepanova and Marina Tsvetaeva, and former editor of the international magazine Modern Poetry in Translation.

This excerpt from IN MEMORY OF MEMORY was published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 2018 by Maria Stepanova. Translation copyright © 2021 by Sasha Dugdale.

Published on February 9, 2021.