This is part of our Campus roundtable on Teaching Medieval in Modern Plague Times.

Like many of our contributors to this pedagogy roundtable, I was caught rather flat-footed when my institution, the University of Houston-Victoria (UHV) in Victoria, Texas, announced that all classes were moving online in March 2020, just a few days after Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson had caught the disease and the entire NBA season was postponed. It’s pop culture moments like these when students and professors alike go, “Oh, this is real, then.” What was “real” was only made more so once thousands began to be hospitalized and the mounting death toll placed most states in lockdown, including Texas in late March 2020. Administrators at UHV opted not to dictate the particular modality once we all got online. Knowing the difficult financial situations and home lives that many of my older, predominantly first-generation students were dealing with, I took all of Spring Break to redesign my US and World History surveys for asynchronous, rather than synchronous, instruction on Blackboard. I assigned readings from textbooks, supplementary online videos and lectures, and weekly, short papers based on what they’d read and seen. The goal was to get through the disruption of the semester in one piece. Many of my students had been either laid off from their jobs or seen their work hours increase as their essential labor was needed in care homes, supermarkets, and retail stores. Judging by some of the student evaluations I received, they appreciated the flexibility that weekly papers gave them during what was now becoming an inescapable pandemic.

But something interesting happened in my World History I survey course, which covers global events from the origins of human civilization to circa 1500. Originally, I had not planned to lecture very much on the Black Death. In regular times, in a typical Medieval Europe course, I usually spend one class day on the Black Death (i.e., the first outbreak in 1348-1353 of the so-called Second Pandemic that ended in Europe around 1722). I usually follow up that class with another on the economic, religious, and social consequences of the plague, one that ushered a considerable number of changes to peasant life and power structures in western Europe in the late fourteenth century. But I was not teaching Medieval Europe. For World History I, I had planned only half a class day on the Black Death. Now, with a pandemic ripping through our community and a new pedagogical imperative that included being easy on the students by giving them short, weekly papers, I assigned the BBC documentary The Return of the Black Death (2014) to supplement our unit on late medieval Europe. The video and topic made many of the students slough off their protective carapaces when they wrote their responses to one of the questions I gave them:

Identify three types of primary sources that historians use to analyze the Black Death/bubonic plague, and explain their particular worth in illuminating the human and social experiences of the plague. BONUS, extra credit: What parallels do you see between how medieval and modern governments handle epidemics?

Almost all answered the bonus question, comparing, for example, the government of the English King Edward III, who had burial grounds prepared for what was to be an onslaught of deaths, to modern governments in Europe and America that have prepared for hospital capacities and morgues being overwhelmed by COVID-19 mortalities. One impassioned voice rose above the rest. This student was frustrated, but clearly wanted to take the time to answer the bonus question. This student wrote: “The only countries [that] are prepared and doing things right are the countries run by WOMEN… Our government should have been more proactive and planned for such a debacle to happen [but it] didn’t….” I’ve left some of the more colorful language out, but this student’s larger point was that, at the time, Angela Merkel in Germany and Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand seemed like the only competent individuals who were properly running the pandemic response for their respective governments.

Truth be told, I live for these kinds of student responses. I understand that many history professors, particularly medievalists, subscribe to the “the past is a different country” approach to pedagogy. I understand and admire this approach. I do think it’s important to highlight, for undergraduate students, how history is not simply a series of events that repeats itself and that—though an event or ideology may bear some resemblance to something or someone modern—context does matter. And compared to our time, that context was very different for peasants, townspeople, politicians, and academics who lived during the medieval period (roughly speaking, from 500 to 1500). But it is also my firm belief that using historical events, even ones far removed in time and space, to reflect on our present is what keeps disciplines like medieval history and European Studies both relevant and interesting to our students. After the tumultuous Spring semester ended, I started to hatch a plan.

I am a legal historian by trade and have had little training in the history of disease and medicine, but given the overwhelming interest in the Black Death, I took advantage of those (deeply lonely) lockdown months during the summer to develop a Special Topics class in European History on “Disease, Plague, and Pandemics in Antiquity and the Medieval World.” Though I taught my Spring classes asynchronously, I knew that during Fall 2020 I would have to teach my courses synchronously—or, how UHV labels them, “Real-Time Online”—using Microsoft Teams, which is the video conferencing software available at my institution. Given the dearth of premodern European history courses in general, and that many courses dealing with the history of disease center on either American or modern experiences, it was also a great opportunity to offer something new and unexpected at a small, regional university in Texas.

The course has one, overall aim: for the students to examine the events and primary sources of the premodern past to see how human behavior, in the face of pandemics and disease, has changed, or not changed, over time. I wanted the students to not only be engaged with the specific contexts and voices of a European past that echoed anxieties about typhus, smallpox, plague, syphilis, and physical disability, but to also reflect on how these voices may or may not speak to our own modern plague times. In my view, history courses not only provide information about the past but can be themselves curative in how they give us—teachers and students alike—intellectual spaces for reflection and empathy.

I designed the final “multimedia” project in the class around the idea that we are living in extraordinary times, and that many educational institutions are and have been collecting personal testimonies from those of us living and working during this pandemic. Lucky for us, the Victoria Regional History Center, which is an archive specializing in the history of the city of Victoria and located in the UHV library, has launched an online archive called “COVID-19 Stories” and is actively collecting stories, images, video and audio recordings from Victoria’s residents to document the effects of the pandemic on the local population.[1] For their final projects, the students in my course are contributing to this archive by writing their own testimonials, comparing their own experiences with Europeans who lived through ancient and medieval pandemics, and providing two digital sources (either two images or an image and another type of media) that encapsulate their lives in Texas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The responses both in and to the class have been encouraging thus far, and I hope our little online class has brought the students in it some comfort—at the very least, consolation in the knowledge that societies in the past have dealt with pandemics and figured out ways to survive and live with them. Learning these histories has been, at least for me, a mental salve and a welcome distraction from the chaotic federal response to COVID-19.

Esther Liberman Cuenca is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Houston-Victoria, where she is the designated Europeanist for the school’s history program. She has previously published in EuropeNow on “Medievalism, Nationalism, and European Studies: New Approaches in Digital Pedagogy.” She has articles forthcoming in Popular Music and The Local Historian.

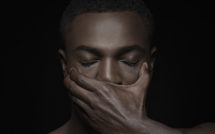

Photo: Medieval plague leather masks, knight’s helmet, hat, transparent chest on a wooden table | Shutterstock

Published on December 8, 2020.